Thomas Keate (1745–1821) was an English surgeon.[1] He became a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1794.[2]

Early life

He was the son of William Keate of Wells, Somerset, and Oxford graduate, and younger brother of the Rev. William Keate (1739–1795), father of John Keate of Eton and Robert Keate.[1][3][4][5][6] A number of sources identify his father as an apothecary in Wells, who became its Mayor.

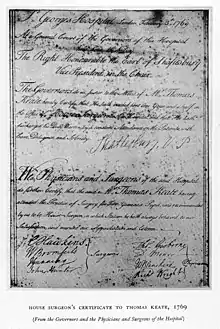

Keate became a pupil at St George's Hospital, London, and later was assistant to John Gunning, surgeon to the hospital.[7] He was appointed regimental surgeon to the 1st Foot Guards in 1778.[1]

Medical career

Keate was surgeon to George,Prince of Wales, afterwards George IV, from 1783 to 1800; he joined the Prince's household set up on his majority, and was a favourite introduced to others of the royal family.[8][9] The low point in the Prince's health came, in his judgement, in 1787, when he was "exceedingly ill".[10] Keate was surgeon to Queen Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz from 1791 to 1803.[8] His 1793 nomination certificate for the Royal Society begins with his royal service.[11]

In 1790 Robert Adair died: he had been surgeon to Chelsea Hospital. Keate was appointed, with a salary. The post at the time was described as close to a sinecure.[12][13] On a vacancy arising in the surgeoncy at St George's Hospital, in succession to Charles Hawkins, there was a sharp contest in 1792 between Keate and Everard Home, whom John Hunter favoured: Keate was elected.[7]

Keate was an examiner at the College of Surgeons from 1800, and master in 1802, 1809, 1818.[7] Representing the College, he witnessed an 1803 electric demonstration with a corpse by Giovanni Aldini in London, accompanied by Joseph Constantine Carpue.[14] As a surgeon, he was the first to tie the subclavian artery for aneurysm.[7]

Army surgeon

Hunter died in 1793, to be succeeded as Surgeon-General to the Army by Gunning, and as Inspector of Regimental Infirmaries by Keate.[7][15] Keate inspected the Savoy Hospital in October of that year, finding six beds in a noisy situation because of prisoners.[16] After Gunning's death in 1798, Keate reunited the posts, becoming also Surgeon-General.[1]

With Lucas Pepys, Keate was blamed for a lack of medical resources and attention in the Walcheren Campaign of 1809.[17] Keate had attended some of the boatloads of wounded soldiers brought up the River Thames.[18] As part of incremental changes in the direction of reform, the existing Army Medical Board of Keate, Pepys and Francis Knight (Inspector-General of Army Hospitals from 1801)[19] was replaced in 1810 by one headed by John Weir, with Theodore Gordon and Charles Ker.[20]

Later life

Unpunctual and slovenly in his hospital duties, in 1813 Keate resigned his appointment at St George's.[7]

Keate opposed the claims made by the surgeon Sir William Adams to have an effective cure for a type of ophthalmia. Adams in 1817 set up a specialised treatment facility within Chelsea Hospital for what is now recognised as a form of trachoma, afflicting soldiers who had served in the Egyptian campaign.[21] With Benjamin Moseley of the Hospital and William North, Keate in 1818 produced outcomes research casting doubt on Adams's treatment.[22] Adams that year moved on started treating gratis for ophthalmia in a new Ophthalmia Hospital built by John Nash on Albany Street, with backing from the Prince Regent. He continued there to 1822.[21][23]

Keate died at Chelsea Hospital on 5 July 1821, aged 76.[7]

Works

On surgery, Keate wrote Cases of Hydrocele and Hernia, London, 1788. In controversy he produced Observations on the Fifth Report of the Commissioners of Medical Enquiry, London, 1808; the report had censured points in Keate's administration.[7]

Family

Keate married in 1784 Emma Browne, daughter of Lyde Browne.[24]

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 Bevan, Michael. "Keate, Thomas (1745–1821)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/15222. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ↑ "Thomas Keate ( 1745 - 1821 )". epsilon.ac.uk.

- ↑ "Keate, William (KT759W)". A Cambridge Alumni Database. University of Cambridge.

- ↑ Foster, Joseph (1888–1892). . Alumni Oxonienses: the Members of the University of Oxford, 1715–1886. Oxford: Parker and Co – via Wikisource.

- ↑ Foster, Joseph (1888–1892). . Alumni Oxonienses: the Members of the University of Oxford, 1715–1886. Oxford: Parker and Co – via Wikisource.

- ↑ Ackroyd, Marcus; Brockliss, Laurence; Moss, Michael; Retford, Kate; Stevenson, John (4 January 2007). Advancing with the Army: Medicine, the Professions and Social Mobility in the British Isles 1790-1850. OUP Oxford. p. 72. ISBN 978-0-19-151483-8.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Lee, Sidney, ed. (1892). . Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 30. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

- 1 2 Burney, Fanny (1972). The Journals and Letters of Fanny Burney (Madame D'Arblay). Vol. 2. Clarendon Press. p. 143.

- ↑ Register, Monthly Literary (1821). The Monthly Magazine. p. 181.

- ↑ Macalpine, Ida (1969). George III and the mad-business. London: Allen Lane. p. 231. ISBN 0712652795.

- ↑ Lawrence, Susan C. (27 June 2002). Charitable Knowledge: Hospital Pupils and Practitioners in Eighteenth-Century London. Cambridge University Press. p. 281 note 70. ISBN 978-0-521-52518-3.

- ↑ The Edinburgh Medical and Surgical Journal. Arch. Constable & Comp. 1845. p. 301.

- ↑ Maclean, Charles (1810). An Analytical View of the Medical Department of the British Army. J.J. Stockdale. p. 88.

- ↑ Morus, Iwan Rhys (2009). "Radicals, Romantics and Electrical Showmen: Placing galvanism at the end of the English Enlightenment". Notes and Records of the Royal Society of London. 63 (3): 269. doi:10.1098/rsnr.2009.0023. ISSN 0035-9149. JSTOR 40647278. S2CID 146244993.

- ↑ Chaplin, Arnold (1918). "Excerpts From The Fitzpatrick Lectures. Delivered Before The Royal College Of Physicians Of London, November, 1918". The British Medical Journal. 2 (3025): 675–679. doi:10.1136/bmj.2.3025.675. ISSN 0007-1447. JSTOR 20336476. PMC 2342389. PMID 20769298.

- ↑ Stevenson, Lloyd G. (1964). "John Hunter, Surgeon-General 1790-1793". Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences. 19 (3): 257 note 60. doi:10.1093/jhmas/xix.3.239. ISSN 0022-5045. JSTOR 24621430. PMID 14193225.

- ↑ Howard, Martin R. (1999). "Walcheren 1809: A Medical Catastrophe". BMJ: British Medical Journal. 319 (7225): 1644–1645. doi:10.1136/bmj.319.7225.1642. ISSN 0959-8138. JSTOR 25186694. PMC 1127097. PMID 10600979.

- ↑ Darley, Gillian (1 January 1999). John Soane: An Accidental Romantic. Yale University Press. p. 166. ISBN 978-0-300-08695-9.

- ↑ The Annual Register, Or, A View of the History, Politics, and Literature for the Year ... J. Dodsley. 1802. p. 63.

- ↑ Crowe, Kate Elizabeth (1973). "The Walcheren Expedition and the New Army Medical Board: A Reconsideration". The English Historical Review. 88 (349): 770–785. doi:10.1093/ehr/LXXXVIII.CCCXLIX.770. ISSN 0013-8266. JSTOR 562934. PMID 11614439.

- 1 2 Tiffany, J. M. "Adams [later Rawson], Sir William (1783–1827)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/23200. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ↑ Kelly, Catherine (6 October 2015). War and the Militarization of British Army Medicine, 1793–1830. Routledge. p. 149. ISBN 978-1-317-32245-0.

- ↑ Summerson, John (1980). The Life and Work of John Nash, Architect. Allen & Unwin. p. 129. ISBN 978-0-04-720021-2.

- ↑ Burney, Sarah Harriet (1997). The Letters of Sarah Harriet Burney. University of Georgia Press. p. 37. ISBN 978-0-8203-1746-5.

External links

Attribution

![]() This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Lee, Sidney, ed. (1892). "Keate, Thomas". Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 30. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Lee, Sidney, ed. (1892). "Keate, Thomas". Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 30. London: Smith, Elder & Co.