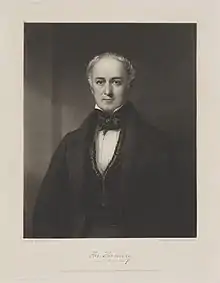

Thomas Thornely, sometimes spelled Thornley, (1 April 1781 – 4 May 1862) was a British Member of Parliament who was one of the elected representatives for Wolverhampton between 1835 and 1859.

Early and business life

Thornely was born on 1 April 1781 in Lord Street, Liverpool, where his father traded as a woollen draper. His parents were both members of well-established Presbyterian families, his father being related to the Thornelys of Hyde in Cheshire and his mother to the Mather family of Toxteth Park. He was schooled for some time by the minister of Hyde Chapel, Bristowe Cooper,[lower-alpha 1] and later apprenticed to the merchant firm of Rathbone, Hughes and Duncan, operated in Liverpool by the William Rathbone family.[lower-alpha 2] He became a merchant in his own right in 1802, trading mainly with the United States, when he joined the firm of Martin, Hope and Thornely as junior partner. Between 1805 and 1810, he was based in New York as the firm's resident partner and he later made a further three visits to the US, the last being in 1842 with his nephew.[3]

On his return to Liverpool, Thornely retained his involvement in commerce, including with the East Indies, and according to an obituary "took much interest in public affairs and in all matters connected with civil, religious and commercial freedom". In 1811, he was among the merchants who condemned the British government's reaction to Napoleon's attempt at an economic blockade of Britain, known as the Continental System, on the grounds that their retaliation was damaging trade with the US. He helped to present evidence to a parliamentary committee regarding the matter and the Orders-in-Council were eventually rescinded, although by that time the War of 1812 with the US had begun. He was a supporter of proposals which eventually were encapsulated in the 1832 Reform Act and of repeal of the Corn Laws,[3] as well as becoming a senior figure in the Liverpool East India Association, which lobbied on behalf of merchants.[4]

When the partnership of Martin, Hope and Thornely was dissolved in the 1810s, Thornely joined with his brother to form the firm of Thomas and J. D. Thornely, with which he remained connected until retirement in 1839.[3][lower-alpha 3] He has been described as being a "sugar refiner"[6]

Thornely was a member and official of the Renshaw Street Unitarian Chapel.[2] He was a vice-president of both Manchester New College and the British and Foreign Unitarian Association, and a regular chapel-goer even when away from his home town of Liverpool. He took an interest in the town throughout his life and was involved in numerous of its institutions, being one of the people involved from the outset of the Liverpool Athenaeum from 1798, and of the Liverpool Literary and Philosophical Society. He was a co-founder of the Liverpool Mechanics' and Apprentices' Library in 1824, as well as being a supporter of the Liverpool Institute from its origination.[3]

Politics

In 1831, Thornely stood in a parliamentary by-election for the Liverpool constituency, losing to Viscount Sandon after campaigning for full acceptance of the proposals that later became the Reform Act of 1832. He lost again in the 1832 election, subsequent to which there were attempts to resolve issues of corruption that had blighted elections in the borough, both municipal and parliamentary, since 1823.[6][7]

Thornely refused to stand as a candidate in Liverpool for the 1835 general election because, according to a report in the Liverpool Mercury, "he felt it was useless to contend with the [corrupt] freemen of Liverpool".[8] He was instead elected as the Member of Parliament for Wolverhampton,[9] together with Charles Pelham Villiers, who noted that the constituency was "one of the new boroughs and, as yet, uncorrupted". Thornely, who had considerable experience in local politics, and the somewhat younger Villiers were re-elected at the next five general elections, became mutual friends and worked closely together. According to biographer Roger Swift, both were "committed Reformers and Free Traders", with Thornely's sagacity sometimes tempering Villiers' impetuous tendencies.[10][lower-alpha 4] At only one of those elections was he opposed.[3]

Aside from his involvement in reform causes such as supporting free trade[11] and repeal of the Corn Laws, Thornely played a significant, if somewhat unobtrusive, role in the passing of the Dissenters' Chapels Act of 1844, which rectified a legal anomaly that had arisen following the recognition by the 1813 Doctrine of the Trinity Act of the right of Nonconformists to practise their religion . The 1844 Act recognised the property rights of Unitarians to the places of worship that they had used for 25 or more years previously.[3][12]

Thornely, who was among the most assiduous attendees in the House of Commons, stood down from the House of Commons at the 1859 general election, being by then aged 78 and suffering from poor health.[13] The Wolverhampton Chronicle noted at his death on 4 May 1862 that he was "Not of brilliant [political] talent, yet his various knowledge on all subjects connected with the extensive commerce of the empire seldom left him at a loss in the House of Commons how to make his opinions respected."[2] Another obituary noted that

He entered the House of Commons as a holder of rather extreme Liberal opinions, but under the influence of experience and of personal knowledge of the working of the great parties in the State, he became one of the steadiest supporters of the Liberal Ministry who conducted the Government. This change, indeed, may have consisted at least as much in the onward movement of the age as in any increased conservatism in him. It was not so much that he moved back as that the age moved on. With scarcely an exception, what were considered extreme views in Mr Thornely's youth, are now looked upon as either accomplished or essential reforms.[3]

Perhaps Thornely's last political act had been to arrange for his interment in his family's vault at the Renshaw Street burial ground. The cemetery had been closed under the provisions of sanitary regulations but he was eventually successful in his appeal to the prime minister, Lord Palmerston, to permit, under strict conditions, the burial of people closely related to those already interred. Palmerston himself had been potentially excluded from interment in a family vault under the same regulations.[3]

References

Notes

- ↑ The Hyde Presbyterian chapel, founded in 1708, lies in Gee Cross and was replaced with a new structure in 1848, at the opening of which Thornely was a speaker.[1]

- ↑ Thornely's friend, John Ashton Yates, was a fellow apprentice at the firm run by the William Rathbone family and also became an MP.[2]

- ↑ The partnership between Thomas and John Daniel Thornely was formally announced as being dissolved in late 1840.[5] John, who was Thomas's only brother, died in 1848; their father had died, aged 95, in 1839, at which time he was living with Thomas, who never married, and Thomas's sister.[3]

- ↑ The point made by Villiers of the Wolverhampton constituency being a "new" borough is a reference to the changes introduced by the Reform Act 1832.

Citations

- ↑ "History and Heritage - Hyde Chapel". Hyde Chapel. Retrieved 26 August 2019.

- 1 2 3 Bebbington, D. W. (April 2009). "Unitarian Members of Parliament in the Nineteenth Century — A Catalogue" (PDF). Transactions of the Unitarian Historical Society. 24 (3): 54.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Aspland, Robert (June 1862). "Memoir of the late Thomas Thornely, Esq". Christian Reformer. XVIII (CCX): 361–384.

- ↑ Kumagai, Yukihisa (2012). Breaking into the Monopoly: Provincial Merchants and Manufacturers' Campaigns for Access to the Asian Market, 1790-1833. BRILL. pp. 116, 144, 146, 154, 217. ISBN 978-9-004241-77-0.

- ↑ "No. 19937". The London Gazette. 5 January 1841. p. 45.

- 1 2 Escott, Margaret. "Liverpool". History of Parliament Online. Retrieved 22 August 2019.

- ↑ Menzies, E. M. (February 1973). "The Freeman Voter in Liverpool, 1802-1835" (PDF). Transactions of the Historic Society of Lancashire and Cheshire. 124. Retrieved 22 August 2019.

- ↑ Collins, Neil (1994). Politics and Elections in Nineteenth-Century Liverpool. Scolar Press. p. 14. ISBN 1-85928-076-5.

- ↑ Craig, F. W. S. (1989) [1977]. British parliamentary election results 1832–1885 (2nd ed.). Chichester: Parliamentary Research Services. p. 338. ISBN 0-900178-26-4.

- ↑ Swift, Roger (2017). Charles Pelham Villiers: Aristocratic Victorian Radical. Routledge. pp. 52–53. ISBN 978-1-35197-467-7.

- ↑ Brown, Lucy (July 1953). "The Board of Trade and the Tariff Problem, 1840-2". The English Historical Review. 68 (268): 394–421. doi:10.1093/ehr/LXVIII.CCLXVIII.394. JSTOR 555868.

- ↑ Wakeling, Christopher (2016). "Nonconformist Places of Worship". Historic England. Retrieved 5 September 2019.

- ↑ Swift, Roger (2017). Charles Pelham Villiers: Aristocratic Victorian Radical. Routledge. p. 174. ISBN 978-1-35197-467-7.