Thomas William (Bill) Ah Chow was a Chinese-Australian soldier, farmer, fire lookout and legendary bushman of East Gippsland in Victoria.

Bill's father, Thomas Ah Chow, was born in Hong Kong in 1834, educated in England, worked initially as a sea-cook and then as a ship's steward. He first arrived in New South Wales in 1855 aged 21 years where his spent his first two years. He later came to Victoria to ply the busy coastal route between Melbourne and Port Albert on steamers transporting miners and their equipment to Gippsland's goldfields.[1] However, the construction of the Sale Canal between 1883 and 1890, which included the Swing Bridge at Longford, gave closer access to the Port of Sale for boats coming via the Gippsland Lakes. This combined with the opening of the Gippsland railway line in 1877 spelled the ultimate demise of the coastal shipping to Port Albert.

Thomas Ah Chow married Agnes Elizabeth Mason on 30 May 1872 and the newlyweds lived in South Melbourne or Emerald Hill as it was known then. The couple eventually settled at Mossiface near Bruthen in about 1880 to become one of the early farming families of the region.[2] Thomas William (Bill) Ah Chow was born at Bruthen on 11 September 1892 as the youngest of 13 children to Thomas and Agnes.

Many Chinese came to the Victorian gold rush in the 1850s to seek their fortune at the Omeo and Cassilis diggings. Many of the immigrants later settled and integrated into their local communities working as farm labourers, tending market gardens, making furniture, running grocery stores and cafes or practising Chinese medicine.[3] However, the large and sudden influx of Asian immigrants to the gold fields gave rise to widespread fears and prejudice about Chinese immigration to Australia. By the time of Federation in 1901, all Australian colonies had enacted legislation restricting Chinese immigration.[2]

These restrictions were part of the White Australia Policy, which sought to ensure that the population remained predominantly British subjects or at least of European origin.[3] The new Federal Parliament passed the Immigration Restriction Act 1901 which allowed the Government to deny entry to people failing an onerous dictation test in any European language chosen by the immigration officer.[3] These policies were progressively dismantled between 1949 and 1973.

Chinese ANZAC

When World War I was declared in 1914 Australia issued a call to arms. At the time, the population was approximately 4.9 million and around 420,000 Australians enlisted for service, representing nearly 40% of the male population aged between 18 and 44.[4]

However, under the White Australian Policy together with the Defence Act of 1909, those "not substantially of European origin or descent" were excluded from serving in the naval and military forces.[2] Moreover, minimum physical requirements such as height and chest circumference made it difficult for young Chinese men of smaller stature to enlist.[2]

Bill Ah Chow attempted to enlist at least twice in the army, first at his home town of Bruthen on 6 May 1915, but was rejected because of his obvious Chinese appearance. Undeterred, he reapplied and was accepted two years later on 19 June 1917 at the nearby City of Sale, where he wrote "No" on his attestation paper to the question "Have you ever been declared unfit for service in His Majesty's service?" It is thought that the recruitment officer must have questioned his answer because it was crossed out and overwritten with a note "yes, not of sufficiently European appearance".[5] However, by this time, the war in France was dragging on and restrictions were being relaxed and Thomas William Ah Chow was accepted.[2]

Bill was assigned to the 25th reinforcements of the 5th Battalion AIF and sailed to France on board the HMAT A-32 Themistocles on 4 August 1917. While serving on the Western Front in France, Bill was not only gassed but also wounded three times, once seriously of a gunshot wound to the right shoulder on 31 July 1918. Bill was repatriated to No 1 Australian Auxiliary Hospital which was set in the grounds of the stately Harefield Park near London and saw no further active service. He sailed home from England to Australia on board the HMAT A-38 Ulysses on 18 January 1919.[5] The community welcomed him with a civic reception at Mossiface on 26 March where he was presented with a small gold medallion.[6] He was later medically discharged from the Army on 19 June 1919.

Like many men of his generation, Bill Ah Chow rarely spoke of his wartime experiences.[7]

Overall the Chinese-Australian community supported the war effort with around two hundred enlisting. Nineteen received gallantry awards and forty were killed in action.[2] One of the most famous and decorated was sniper, Billy Sing.

Farmer

Before the War, Bill took a job as a farm roustabout and boundary rider on the remote and historic Bindi Station east of Omeo which was established in 1834 and holds one of the earliest property titles issued in Victoria.[8] In April 1912 he reported finding the dead body of Charlie Price at Scrubby Creek to Omeo police while he was out looking for bullocks.[9] David Kelly was later charged with murder.

After the War, Bill returned to Bruthen where he drove sheep and worked cattle. He married Myrtle Cox in 1920 and they initially lived in Swan Reach. The couple had two children Raymond William (1921) and Rose Myrtle (1923).

In 1923 he applied for, and after some initial rejections was granted, two small allotments of land totalling 111-2-2 acres under the Soldier Settlement Scheme in the Parish of Bumberrah near Mossiface. Bill stayed on his block until 30 March 1926 but his oat and maize crops were not a success. He also experienced significant medical problems, partly because of his war injuries, including shortness of breath and his shoulder injury proved a major impediment for life as a farmer.[10]

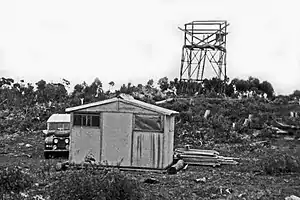

Bill and his family then moved to Buchan South and later to Ensay in the Upper Tambo Valley where they lived in the old school house on the edge of town. It is also believed that Bill helped to construct the wooden fire tower at Mount Nowa Nowa for the Forests Commission Victoria (FCV) in 1926/27 when he lived at Buchan South.[11]

Fire Towerman

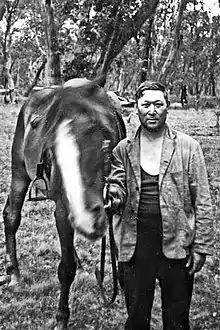

In the late 1930s, with his good local knowledge of the mountain ranges, Bill was offered a new job as a fire lookout over the summer months by the local Forests Commission Victoria District Forester, Jim Westcott.[8] Bill was paid a wage as a Fireguard plus allowances for camping and for providing his own riding horse, packhorse with packsaddle and saddle bags. Provisions and fodder for his horses, were purchased in Bruthen and delivered once a fortnight by the local FCV officer assigned to oversee the area.[7]

As a Fireguard, Bill's primary role was to spot and report on bushfires from Mt Nugong about 30 km east of Swifts Creek. Riding his horse and leading the pack horse loaded with a portable RC-16 radio[12] (callsign VL3BB), heavy spare battery and the provisions for the day, he made the journey up the steep bridle path 3 km from Bentley's Plain to the summit. After unloading his packsaddles, Bill often let both his horses roam free to make their own way home back down to Bentley's Plain.[7]

The Forests Commission also established a Weather observation station at Bentley's Plain in 1950 and Bill read the thermometers, measured rainfall, estimated cloud cover, wind speed and direction, recorded the observations and transmitted the information by radio to the FCV office at Bruthen which were then sent to the Bureau of Meteorology once a month.[7]

_Ah_Chow_-_building_forest_roads_with_his_two_Clydesdales.tif.jpg.webp)

At the end of the summer fire spotting season, and after the first good rain of autumn, Bill set off alone on his horse along the many bridle paths that cross-crossed the alpine country as far as the NSW border throwing matches along the way to burn forest fuels and reduce the bushfire risk. Bill would often rendezvous at Limestone Creek with another Fireguard, Charlie Pendergast based at Benambra on a similar expedition.[7]

When not on fire lookout duty Bill assisted local Forests Commission crews building nearby forest roads after the 1939 bushfires. The work entailed removing trees with explosives and dragging the stumps with his Clydesdale work horses. The horses also pulled a heavy plough to break out the formation, dragged a grader to shape the surface and moved sections of concrete culvert pipe. However, there was still plenty of hard work for the men with hand tools as well handling the horses and explosives.[7]

The new roads provided access for firefighting and for logging crews. The nearby Washington Winch was imported into Australia in 1920 and operated initially in Western Australia before being purchased by the Forests Commission for 1939 bushfire salvage logging the Central Highlands around Noojee. It was later sold and moved to its present site by local sawmilling company Ezards in 1959 where it operated until 1961–62. It remains the only high lead-skyline logging system left in Victoria and is listed on the State Heritage Register.[13]

Mt Nugong Fire Tower

Mt Nugong sits at an elevation of 1482 m, about 3 km from Bentley's Plain. The summit has commanding views over the extensive mountain forests as well as the Tambo Valley below and was one of a network of fire lookouts (hilltop clearings) and fire towers (built structures) created across Victoria as consequence of the Stretton Royal Commission into the disastrous 1939 Black Friday bushfires.[11]

Prior to a fire tower and Stanley Hut being built, there was no shelter from sun, wind or cold. In 1952 the Forests Commission scrounged a decommissioned control tower from the RAAF at Bairnsdale Airfield, but the tubular-steel scaffold needed to transported and re-assembled by local FCV crews. There were many logistical difficulties erecting the heavy metal tower because there were no roads to the summit. The structure at Mt Nugong did not include the RAAF air traffic controllers cabin and was still open to the elements until a rudimentary shelter was added in about 1954.[7]

Bill often boasted about his eagle eyesight but also complained that the Forests Commission would not issue him binoculars. The new firetower was eventually equipped with an alidade to record compass bearings to smoke sightings and lightning strikes as well as a fixed radio set to communicate with Bruthen or Swifts Creek.[1] Bill worked for the Forests Commission as towerman at Mt Nugong for more than two decades until 1957 but sometimes came out of retirement when a replacement towerman couldn't be found.[7]

This first tower survived two more decades before a storm blew it down in 1974 and it needed to be rebuilt.[11]

Moscow Villa

When Bill became a fire spotter for Forests Commission Victoria he camped at Bentley's Plain on the Nunniong Plateau about 30 km east of Swifts Creek. Bentley's Plain was named after John Bentley who was sentenced in 1866 along with James Neville before his Honour Sir Redmond Barry to two years with hard labour for stealing cattle.[14]

Bill helped to build Commins Hut and cattle yards on Quinn's Plain in 1937 for James (Jim) Commins and Charlie Duke who leased the Nunniong Cattle Run. It was used when mustering stock and Bill Ah Chow also stayed there prior to building his own hut.

_Ah_Chow_-_Commins_Hut_1951._Nunniong_plains.tif.jpg.webp)

Bill then built himself a substantial log hut he named "Moscow Villa" which was completed in January 1942, on the day the Battle of Moscow was won.[15] Bill used local wood to build the hut and hand split the palings. Initially it had an iron chimney which was later replaced in 1975 by large one made of local stone. There was also a large bushfire dugout in the nearby bush. Bill lived in Moscow Villa during the summer months and in winter returned to his family in Ensay.[7]

While there are some variations to the story, which is common with oral history, bush folklore has it that Moscow Villa was visited at some stage between 1942 and 1947 by a party of senior Forests Commission officials which included Herbert Duncan Galbraith, the Divisional Inspector from Bairnsdale who later became Commissioner, whereupon Bill was challenged about his loyalty and the name of his hut. Bill swiftly retorted that he was not a communist and that the name was an acronym for "My Own Summer Cottage Officially Welcomes Visitors Inside Light Luncheon Available".[7] The visit was during the McCarthyist era and the tensions of the Cold War when Prime Minister Sir Robert Menzies was attempting to ban the Communist Party of Australia. Bill's quick wit and humour prevailed and his hut retained its quirky name.[16]

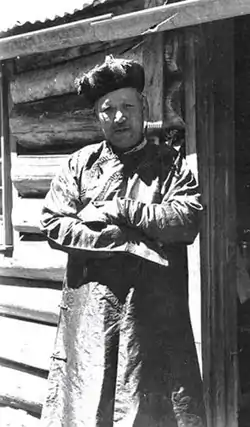

Bill had a reputation for welcoming walkers, fishermen and foresters into his comfortable hut to sit around the fire, to share a meal, and enjoy an evening of bush yarns. He was also very proud of his Chinese heritage and would, with little encouragement, don traditional dress for his guests.[7]

Moscow Villa is currently maintained by the Department of Environment Land Water and Planning (DELWP) with the support of the Victorian High Country Huts Association[17] and is one of the very few traditional mountain huts to have survived bushfires, neglect and vandalism and remains Bill Ah Chows' legacy as a popular camping site and snow refuge. The floor was replaced and rotten timbers removed in 1999, and once again in 2018. The stone chimney was built in 1975 by local Forests Commission crew (Brian Shelton, George Gallagher, Gary Antonoff & Peter Walker). The inside loft and wooden table were made by the local DELWP carpenter Brendan Purcell and Bill's family provided material and photos for the information boards inside.

Inconsistencies with some of Bill's historical records

Thomas William (Bill) Ah Chow died on 18 August 1967 at Omeo, aged 74*, and is buried at Ensay cemetery.

* However, some interesting but minor discrepancies come to light when studying Bill's headstone at the Ensay Cemetery. The simple Department of Veteran Affairs brass plaque displays a small Christian Cross, Rising Sun Badge of the ADF and cameo photo of Bill (which is the key link) and describes the grave as belonging to "William" Ah Chow rather than "Thomas William" Ah Chow and his age of death is incorrectly stated as 70 rather than 74. These anomalies were double checked against his World War I Army Service records held in the Australian National Archives, the Australian War Memorial records, the Victorian Register of Births, Deaths and Marriages and those held at the Victorian Public Record Office. They reveal:

- The Victorian Register of Births, Deaths and Marriages records "William Thomas" Ah Chow as being born at Bruthen in 1892 with his father as Thomas and his mother Agnes (Mason).

- When Bill first tried to enlist in the Army on 6 May 1915 he has clearly handwritten "Thomas William" at the top of his attestation papers and signed as "Thomas William" at the bottom. He states his father, Thomas Ah Chow from Mossiface/Bruthen, as his next-of-kin and correctly states his age as 22 years, 8 months (i.e. born September 1892).

- At his second successful attempt to enlist on 19 June 1917 he has once again written "Thomas William" at the top but this time signed as "William Thomas" at the bottom. He also states his age incorrectly as 25 years and 9 months. (i.e. born September 1891).

- The Australian National Archives have all his military records stored under "Thomas William" AhChow (one word). All the correspondence on his file is signed T W Ah Chow.

- The Australian War Memorial has Bill listed as Private No. 7740 "Thomas William" Ah Chow on the 1917 embarkation roll.

- But records show he married Myrtle Cox on 22 December 1920 as "William Thomas" Ah Chow.

- Then his application for land under the Soldier Settlement Scheme in April 1923 was made under the name and signature of "Thomas William" Ah Chow, aged 30 (i.e. born September 1892).

- Lastly, the Victorian Register of Births, Deaths and Marriages record that "William Thomas" Ah Chow died at Omeo in 1967, aged 74, and both his place of birth and parents names coincide with those on his birth certificate.

There is no suggestion of impropriety and no explanation is advanced. However, these inconsistencies make it difficult for family genealogists. But to everyone who knew him, he was simply Bill.[2]

Gallery

_Ah_Chow_-_Original_family_Home_Mossiface.jpg.webp) Thought to be Bill's family home in Mossiface (c. 1905)

Thought to be Bill's family home in Mossiface (c. 1905)_Ah_Chow_-_his_father_Thomas_Ah_Chow.jpg.webp) Thomas Ah Chow - Bill's father (c. 1905)

Thomas Ah Chow - Bill's father (c. 1905)_Ah_Chow_-_age_15yrs.tif.jpg.webp) Young Thomas William Ah Chow aged 15.

Young Thomas William Ah Chow aged 15._Ah_Chow_-_at_home_at_Mossiface_before_being_deployed_to_WW1.jpg.webp) Thomas William Ah Chow - Aug 1917 before heading of to WW1

Thomas William Ah Chow - Aug 1917 before heading of to WW1 Ensay - Upper Tambo Valley. Circa 1900.

Ensay - Upper Tambo Valley. Circa 1900. Moscow Villa - 1949. With iron chimney

Moscow Villa - 1949. With iron chimney Moscow Villa - summer 1952/53. Canvas shelter at front. Source: Athol Hodgson

Moscow Villa - summer 1952/53. Canvas shelter at front. Source: Athol Hodgson Inside Moscow Villa - 1951

Inside Moscow Villa - 1951 Bill Ah Chow with horses - probably at Ensay.

Bill Ah Chow with horses - probably at Ensay. Bill Ah Chow at Moscow Villa with two unidentified bushwalkers

Bill Ah Chow at Moscow Villa with two unidentified bushwalkers Bill Ah Chow. Museum Victoria image c. 1939

Bill Ah Chow. Museum Victoria image c. 1939_Ah_Chow_-_in_his_Chinese_Robes.tif.jpg.webp) Thomas William Ah Chow - Chinese costume (c. 1950)

Thomas William Ah Chow - Chinese costume (c. 1950) Thomas William Ah Chow - Studio Photo

Thomas William Ah Chow - Studio Photo_Ah_Chow_-_burning_off_-_Bentley_Plain.tif.jpg.webp) Burning off near Moscow Villa. Circa 1951

Burning off near Moscow Villa. Circa 1951_Ah_Chow_-_Forests_Commission_Camp.tif.jpg.webp) Thomas William Ah Chow - at Forests Commission Victoria camp. Circa 1951

Thomas William Ah Chow - at Forests Commission Victoria camp. Circa 1951_Ah_Chow_-_Bentley_Plain_carrying_water_to_Moscow_Villa.tif.jpg.webp) Collecting water near Moscow Villa. Circa 1951

Collecting water near Moscow Villa. Circa 1951_Ah_Chow_-_shodding_his_horse_-_Bentley_Plains.tif.jpg.webp) Moscow Villa - 1951

Moscow Villa - 1951 Bill Ah Chow at Moscow Villa. circa 1955

Bill Ah Chow at Moscow Villa. circa 1955 Forests Commission Victoria - network of fire lookouts (hilltop clearings) and fire tower structures - 1945. Mt Nugong was a lookout.

Forests Commission Victoria - network of fire lookouts (hilltop clearings) and fire tower structures - 1945. Mt Nugong was a lookout. Mt Nowa Nowa fire tower was built in 1926/27 by the Forests Commission Victoria. It is believed that Bill Ah Chow helped with its construction. Photo Jim McKinty 1949.

Mt Nowa Nowa fire tower was built in 1926/27 by the Forests Commission Victoria. It is believed that Bill Ah Chow helped with its construction. Photo Jim McKinty 1949. Mt Nugong. The cabin was added in about 1954/55. Photo taken by Melbourne bushwalking club.

Mt Nugong. The cabin was added in about 1954/55. Photo taken by Melbourne bushwalking club. Moscow Villa - 2003

Moscow Villa - 2003 Moscow Villa in 2006. The large stone chimney was added in 1975 by local FCV crews.

Moscow Villa in 2006. The large stone chimney was added in 1975 by local FCV crews. The historic Washington Winch is near to Moscow Villa.

The historic Washington Winch is near to Moscow Villa.

See also

The US Forest Service engaged the first female fire lookout – Miss Hallie Morse Daggett in 1913.

References

- 1 2 Bill Ah Chow. Moscow Villa mountain man. The Age 27 April 1960. Page 13.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Chinese ANZACs".

- 1 2 3 "History of immigration from China".

- ↑ "Enlistment statistics, First World War".

- 1 2 "Australian National Archives".

- ↑ Welcome Home Bruthen & Tambo Times 27 March 1919, p. 3

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 "Victoria's Forest Heritage".

- 1 2 "Returning to Civilian Life: Thomas William "Bill" Ah Chow".

- ↑ "Settler Shot in the back". The Argus. 26 April 1912.

- ↑ "Battle to Farm".

- 1 2 3 "Fire Lookout Towers in Victoria, Australia".

- ↑ "R.C. Radio phone for all types of forest work.," Victorian School of Forestry, Creswick Campus Historical Collection".

- ↑ Vict Heritage database (2008). "WASHINGTON WINCH".

- ↑ "Beechworth Court Circuit". Ovens & Murray Advertiser. 17 April 1866.

- ↑ "Moscow Villa".

- ↑ "KHA - Moscow Villa".

- ↑ "Victorian High Country Huts Association".

External links

McHugh, Peter. (2020). Forests and Bushfire History of Victoria : A compilation of short stories, Victoria. https://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-2899074696/view

FCRPA - Forests Commission Retired Personnel Association (Peter McHugh) - https://victoriasforestryheritage.org.au