Thomas Young Hall (25 October 1802 – 3 February 1870) was an English mining engineer and coal mine owner. A native of Tyneside, he was a well-known figure in Newcastle in the mid-nineteenth century.

Early life

He was born in Greenside on 25 October 1802. His father, James Hall, was a mining engineer, manager of the Folly Pitt, and agent to several leading coal mine owners including the Dunns, G. Silvertop, Capt. Blackett, W. P. Wrightson, P. E. Townley, and John Buddle.[1]

With this background, Welford's assertion that T. Y. Hall started work as a pit-boy out of economic necessity seems unlikely.[2]

Young Thomas received his education at the Crawcrook school, also known as Craiggy's School after the father and son, John and John Alexander Craiggy, who acted successively as Master. Crawcrook was at the centre of the coal mining industry at that time and other eminent pupils included Sir George Elliot, Nicholas Wood, J. B. Simpson and others who were to become eminent mining engineers in Europe, and America. Bourn comments, "it is a question whether any other village school in England has turned out so many distinguished men who have been connected with the coal trade". Thomas entered the mines and was apprenticed to his father and John Buddle at Towneley, Whitfield and Crawcrook collieries.[1]

Early career

At the age of 22, he became under-viewer at the North Hetton Colliery. After four years, he joined Jonathan Backhouse at the Black Boy and Coundon pits. This period, which coincided with the early years of the Stockton and Darlington Railway, introduced him to the importance of costing the transport of coal to the nearest ports. He reported on the potential for exploitation of the Coxhoe, Shadforth and Sherburn pits, which led to the development of Hartlepool as a coal port.[2] By 1832, he was a director and shareholder in the Old Hartlepool Docks and Railway Company.[3] Fordyce[4] subsequently reported the opening of Hartlepool Docks on 9 July 1835, as follows: "That stupendous undertaking, the Hartlepool docks and harbour, was opened for the shipment of coal and merchandize. The day being extremely fine, great rejoicings took place. The first shipment of coals was made in the Britannia of Sunderland, Tyne and Wear. Having taken her cargo on board, she proceeded to sea amid the ringing of bells, the firing of cannon, and the acclamation of those who had assembled to witness the ceremony." The first shipment of South Hetton coal, following the completion of the South Hetton railway branch, followed on 23 November 1835.

In late 1832, Hall became mining engineer at South Hetton in addition to his other duties. Over the next four years, he made his first major contribution to the mining industry by developing the tub, cage and guide-rod system for raising coal from the pit,[5][2] Established practice had been to bring coal to the surface in wicker baskets or "corves". These had increased in size over the years from 3 cwt. to about 6 cwt., making them difficult to fill and handle underground and prone to snagging while being lifted in the shaft. Adding to the difficulties was the common practice amongst miners of hanging to the ropes or lifting chain to ascend and descend the 1500 ft or more of the pit shaft. Hall replaced the corves with low tubs which ran on rails underground. Initially these were emptied at the shaft bottom, but he subsequently developed a frame or cage into which several tubs could be loaded for lifting. To prevent the cage fouling the sides of the shaft, he developed an idea proposed initially by a Mr. Curr of Sheffield and fitted guide rods to constrain it. A model of the system was exhibited at the Polytechnic Exhibition, Newcastle, and the Museum of Practical Geology, London.

These developments had a profound effect on mining costs which Hall later quantified as a saving of 1s.3 d. per ton of coal or over £1m. p.a. for the NE Coalfield [6] By 1836, Hall was entering a partnership with Buddle and Potter to work the Ryton Glebe and Stella collieries. This soon extended to the Townley Main and Whitefield pits, and workings in the Crawcrook area. The group became known as the Stella Coal Company and traded successfully until the 1860s. Hall became resident at Stella House and, as part of the developments, leased an area of land to the west of Blaydon Burn.[7] As his principal interest was the development of the Stella staithes, land was sub-leased to a range of industrial users including an acid and white lead factory. These complex legal arrangements were to return to haunt him in later life.

America

In the late 1830s, the Blackheath Colliery, Etna and Mid-Lothian pits in Cleveland County, Virginia, were devastated by fire and explosion, resulting in what the NEIMME reported as "sacrifice of life in negro workmen". The best American engineers failed to clear the resultant gas and Col. Heth, the Managing Partner, visited London to consult the eminent Engineer, Robert Stephenson.[8] On Stephenson's recommendation, Hall and Frank Forster, Engineer to the London Sewerage Company, visited Virginia. Within a month, it is claimed that Hall, assisted by one NE pitman who had accompanied him, had restored the mines to working condition.[2] This was clearly a highly lucrative development for Hall. For restoring a mine valued at £50k, he was initially offered £10k for his involvement, subsequently amended to a £7k share option and a five-year term as Mining Superintendent on a salary linked to production (and frequently quoted as circa £2k p.a.). Following the intervention of Thos. Wood,[9] it was agreed that Hall should receive " normal Viewers' customary perquisites" and be allowed to pursue private work for three months in the year. This led to him crossing the Atlantic 16 times between 1839 and 1843,[7] no mean achievement in the age before steamships were fully established. The Agreement for the formation of the Chesterfield Coal & Iron Mining Company dated 30 April 1840,[10] lists John Heth (Virginia), Charles Scarrisbrick (Lancaster) George Morten (Old Bond St.), Thos Wood (Castle Eden) and Samuel Amory (Throgmorton St.) amongst the directors. Arrangements for Hall are detailed, even specifying that during his time in America he should have, "two horses for his use and the keep of a cow". Welford notes that having an English company holding assets in America caused constitutional issues, requiring negotiations with the American Government. During his time in America, Hall took an interest in mining in Russia, including the publication of a letter in the New York Herald in 1840 arguing the case for a railway from St.Petersberg to Moscow. This led to Gen. Tcheffkine, the Czar's Director of Mining, and a Russian delegation visiting Tyneside to study railway and mining practice. The party spent several days at Stella with Hall and the local Consul, John Thomas Carr, presenting Hall with a gold medal and letter of appreciation from the Czar,[8]).

Later career

On his permanent return to Tyneside in 1843, residing at 39, Collingwood St., Hall was an established and secure figure. In addition to his lucrative mining and property holdings, he is listed as a shareholder in the Old Hartlepool Docks and Railway Company, Newcastle, Shields and Sunderland Union Banking Co., Scotswood Bridge Co., and J.S.Challoners, Scotswood Rd...[11] Additionally, he had an interest in the Ovingham Bleachery, George Hartford & John Reed and the Middlesbrough Sail Cloth Co. Unfortunately, the late 1840s seem to have been a bad time for business. Correspondence from the period tells of a series of failures.[12] In May 1847, the Middlesbrough Sail Cloth Company was heading for bankruptcy and Hall was referring to the Banks, "going wrong". William Thompson Dixon, Sailcloth Manufacturer, has managed to pay only 5/3 in the £. By December, even Hall himself is being refused further credit by Balamore Mills on the supply of flax for his bleachery. Finally, in March 1848, the Union Bank is appealing to its members for additional funding to stave off its collapse.[13] A further concern during this period was the developing problem with the Stella Haugh land. Townley, who had previously controlled the lease, sought to demonstrate that Hall had neglected his duties as lessee and landlord, which would potentially have allowed him to benefit from the considerable investment which Hall and his sub-lessees had made over more than a decade. The case was heard as Molyneux v. Hall before Mr. Justice Williams at the Durham Summer Assizes on 30 July 1851.[8] Mr. Justice Williams reduced the argument to five points of law, on all of which the jury found predominantly for the defendant, Hall.

Publications

In 1851, Hall, a lifelong bachelor, was living with two servants at 11, Eldon Square.[14] This coincided with the formation of the North of England Institute of Mining and Mechanical Engineers and over the following years he contributed a number of leading papers to their Proceedings, drawing on his extensive knowledge of the coal industry internationally. His definitive work on the North East Coalfield appeared in 1854,[15] including a detailed map. This was followed by the companion paper on the ports of the region in 1861.[16] Hall defended vigorously the position of the Tyne, possibly because of his vested interests, but also made a strong case for the development of Redcar as a 40 ft. deep water port to transport iron ore to Tyneside for smelting. He clearly took a keen interest in the development of North Yorkshire's iron deposits, as shown by the inclusion of the Yorkshire and Cleveland Railway Bill, 1854, in his bound papers,[17]

Other papers analysed the potential of leading overseas coalfields. His paper on Styria and Austria[18] presented his usual factual analysis of production and transport issues backed by economic analysis, but members were then treated to a review of his 1854 summer holiday with slides of the Adelsberg Grotto.

His 1856 paper on the potential of the United States[19]) was informed by his years in Virginia, where the short rail links to the James River were a particular attraction. He was also aware of Pennsylvania's large reserves, which have been exploited to the present day. Although he had spent some months in France,[8] his Notes on the production and consumption of coal in France[20] draws heavily on the centralised returns of the French Legislature, which operated from 1832. This includes telling detail of the 20% drop in production that accompanied the Revolution around 1848. Although he had visited Shanghai, his paper on China relied heavily on the tour of Mr. Samuel Mossman [21] Hall noted that coal had been mined there since 200 BC, but considered the industry very backward and ended his paper with an exhortation to capitalists and engineers to seek concessions there.

Technical developments

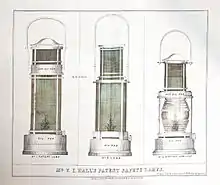

In addition to his economic insights, Hall was involved in several technical developments. Following the Stephenson / Davy controversy about the origins of the safety lamp, opinion was divided between gauze and glass lamps: it was argued that the former could, in some circumstances, be unsafe whereas the latter sometimes gave only limited light. Hall was party to an ingenious set of experiments initiated by Nicholas Wood at the Killingworth and Wallsend Collieries[22] Hall's solution was a series of designs incorporating both gauzes and glass, which were published following the experiments,[23]

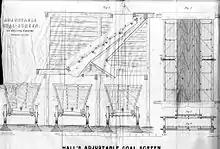

Other developments concerned boiler level indicators, coke ovens and screens for coals. He was also the first in the region to use pit gas for underground lighting[8]

In 1853, Hall was attracted to a prize offered by the Belgian government for rescue systems from mines filled with dangerous gases. His original essays are preserved in English and the French translation,[24] and were subsequently published in the NEIMME Transactions.[25]

Decline and death

In the mid-1860s, Hall prepared a report on the Coalbrook and Broadoak Collieries at Loughor, Glamorgan,[24] The intended business model appears similar to the earlier American activity, with the key investors being Sir William Milman, Messrs Manning and O'Donoghue. Relations between the partners appeared to sour between February and May 1866, by which point relations had broken down with the threat of legal action[26] At the same time, relations with the Simpsons, who managed the Stella assets, became strained[27]

At this time and clearly under considerable pressure, Hall suffered a stroke which incapacitated him for at least 12 weeks. It appears that he spent his remaining years quietly. In 1865, he had been contemplating the purchase of the Villa Real in the Morpeth area, but the sale did not proceed. Bourn[1] states that he retired to Wylam Hill Farm. He died at his Newcastle residence, 11, Eldon Sq., on 3 February 1870 and his funeral was at Ryton church.[28]

Scholarship bequest

Hall maintained his commitment to learning and scholarship. As recorded in the Transactions of the NEIMME,[29] "... a clause in the will of the late Mr. Thos. Y.Hall, which provided that the interest on £500 would be available for a scholarship connected with the college, which he (the President) hoped would soon be formed in connection with this Institute". This endowment provided the Thomas Young Hall Exhibition at the College of Physical Science, which is still awarded to a pre-eminent undergraduate in the Faculty of Science, Agriculture and Engineering at Newcastle University.

References

- 1 2 3 Bourn W. The Parish of Ryton including the Parishes of Winlaton, Stella and Greenside. G.& T.Coward, The Wordsworth Press, Carlisle, 1896. Retrieved in February 2013 from History of Ryton

- 1 2 3 4 Welford R. Men of Mark 'Twixt Tyne and Tweed, Vol. II. p.421 et seq. Walter Scott, (1895)London, 1895. [Internet] Retrieved July 2013 from Men of Mark

- ↑ Durham County Records Office (DCRO)Bound papers. DCRO, NCB01/TH11 p.52 (1832)

- ↑ Fordyce W.Local Records, Vol. III, or Historical Register of Remarkable events 1833–66 T. Fordyce, 60 Dean St., Newcastle upon Tyne, 1867.

- ↑ Hall T.Y.Correspondence 20 September 1834. DCRO NCB01/TH14(1834)

- ↑ Hall T.Y. Notes on the production and consumption of coal in France Trans. NEIMME, (1858)Vol.6, p.49, Newcastle upon Tyne, 1858

- 1 2 NEIMME TYHall's papers, Folder 2C10 – Blaydon Lease, NEIMME, Newcastle upon Tyne, 1841.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Fordyce W. The History and Antiquities of the County Palatine of Durham, Vol. II. (1857)

- ↑ Wood T.Bound Correspondence, DCRO NCB01/TH11,1840, p.42.

- ↑ DCRO Agreement for the formation of the Chesterfield Coal and Iron Company. DCRO, NCB01/TH11 p.33.

- ↑ DCRO Bound papers. DCRO, NCB01/TH11 p.50(1841)

- ↑ DCRO Bound papers. DCRO, NCB01/TH08.(1847)

- ↑ DCRO Bound papers. DCRO, NCB01/TH11 p.81. (1848)

- ↑ 1851 Census. [Internet] Accessed June 2013 at: www.ancestry

- ↑ Hall T.Y. A Treatise on the Extent and Probable Duration of the Northern Coal-Field. Trans NEIMME, Vol.2, p.104, Newcastle upon Tyne, 1854.

- ↑ Hall T.Y. On the Rivers, Ports, and Harbours of the Great Northern Coal-Field. Trans. NEIMME, Vol.10, p.41, Newcastle upon Tyne, 1861.

- ↑ Yorkshire and Cleveland Railway Bill. TYHall's papers, Vol.2, NEIMME, Newcastle upon Tyne, 1854.

- ↑ Hall T.Y. The Coal Measures of Styria in the Austrian Dominions. Trans NEIMME, Vol.4, p.55, Newcastle upon Tyne, 1855.

- ↑ Hall T.Y. Statistical Notes on the Coal and Iron Production of the United States of America. Trans NEIMMEVol.4, p.125, Newcastle upon Tyne, 1856.

- ↑ Hall T.Y. Notes on the production and consumption of coal in France Trans. NEIMME, Vol.6, p.49, Newcastle upon Tyne, 1858

- ↑ Hall T.Y. Progress of Coal-Mining in China. Trans. NEIMME, Vol.15, p.67, Newcastle upon Tyne, 1865.

- ↑ Wood N.Experiments to test various safety lamps, tried at Wallsend Colliery. Trans NEIMME, Vol.1., p.316., Newcastle upon Tyne, 1853.

- ↑ Hall T.Y. On the safety-lamp for the use of coal miners. Trans NEIMME, Vol.1., p.323., Newcastle upon Tyne, 1853.

- 1 2 TYHall's papers, Vol.2, NEIMME, Newcastle upon Tyne, 1853

- ↑ Hall T.Y. On Penetrating Dangerous Gases. Trans NEIMME, Vol.2, p.87, Newcastleupon Tyne, 1853

- ↑ DCRO Bound papers. DCRO, NCB01/TH41.(1866)

- ↑ DCRO Bound papers. DCRO, NCB01/JS30.(1866)

- ↑ Courant Obituary notice. The Newcastle Courant, 2nd Edition, 5 February 1870, Newcastle upon Tyne. (reprinted, 1st Edition, 11 February 1870)

- ↑ NEIMME Minutes of meeting of August, 6th. Trans NEIMME Vol.19, p.188, Newcastleupon Tyne, 1870,

Sources and further reading

Abbreviations: NEIMME: North of England Institute of Mining and Mechanical Engineers DCRO: Durham County Records Office