| Thunderhead Mountain | |

|---|---|

A snow-capped Thunderhead Mountain of the Great Smoky Mountains range rises above Cades Cove in Blount County, Tennessee | |

| Highest point | |

| Elevation | 5,527 ft (1,685 m)[1] |

| Prominence | 1,087 ft (331 m)[1] |

| Listing | Highest point in Blount County[1] |

| Coordinates | 35°34′07″N 83°42′23″W / 35.5685980°N 83.7063208°W[2] |

| Geography | |

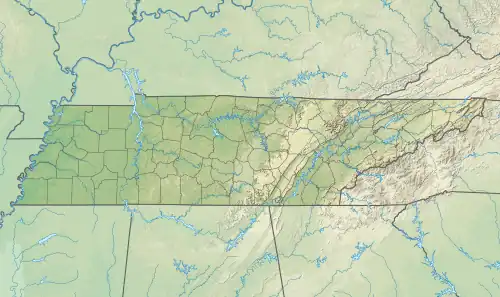

Thunderhead Mountain Thunderhead Mountain (Tennessee)  Thunderhead Mountain Thunderhead Mountain (North Carolina) | |

| Location |

|

| Parent range | Great Smoky Mountains |

| Topo map | USGS Thunderhead Mountain |

| Climbing | |

| Easiest route | Lead Cove Trail, Bote Mountain Trail and Appalachian Trail |

Thunderhead Mountain is a 5,527-foot (1,685 m) mountain in the west-central part of the Great Smoky Mountains, located in the southeastern United States. Rising along the border between Tennessee and North Carolina, the mountain dominates the western Smokies. The Appalachian Trail crosses its summit, making it a popular hiking destination. Rocky Top, a knob on the western part of the mountain's summit ridge, shares its name with a popular Tennessee state song.

Description

Thunderhead rises approximately 3,500 feet (1,100 m) above its northern base at Little River and approximately 3,000 feet (910 m) above its southern base at Bone Valley. The mountain consists of three peaks, the lowest being Rocky Top at 5,440 feet (1,660 m) above sea level and the easternmost being the highest at 5,527 feet (1,685 m) above sea level. Thunderhead is the highest point in Blount County, Tennessee[3] and the highest point on the Appalachian Trail coming from the south until the trail ascends Silers Bald 5,607 feet (1,709 m) some 10 miles (16 km) to the east.

The mountain's name originated in the 19th century.[4] It probably referred to the unpredictable weather that often strikes the higher elevations in the Smokies. According to Laura Thornborough, a writer who hiked to the summit of Thunderhead along with local guide Sam Cook in the 1930s:

"As we proceeded in a near-gale to Rocky Top, the first of the three major peaks of Thunderhead, Sam remarked, "It'll be thunderin' and lightnin' on Thunderhead when it's clear on every other peak on top o' Smoky, and that's how it got its name."[5]

Geology

Thunderhead consists of Precambrian sandstone.[6] Thunderhead sandstone is part of the Ocoee Supergroup, which was formed from ancient ocean sediments between 500 million and one billion years ago. The mountain was formed about 200 million years ago during the Appalachian orogeny, when the collision of the North American and African plates thrust the rock upward.[7]

History

James Spence, who cleared the ridge two miles (3.2 km) to the west (now known as Spence Field), was the first known permanent settler in the vicinity.[8] While the extent of Spence's farm is unknown, cattle grazing had rendered Thunderhead a grassy bald by the late-19th century.[9]

Thunderhead is one of the few mountains listed under its current name in Arnold Guyot's 1859 survey of the crest of the Smokies. Guyot measured Thunderhead's elevation at 5,520 feet (1,680 m) above sea level, missing the modern measurement by just seven feet (2 m).[4]

During the Civil War, a group of East Tennesseans attempted to form a wilderness settlement on the mountain's north slope known as "New World," although the settlement did not last long.[9] The settlement was located along Thunderhead Prong, near Chimney Rocks.

As preservationist groups began buying land in the Smokies in the early 20th century, Thunderhead became a favorite hiking destination for park visitors. John W. Oliver, the great-grandson of the first European settlers in Cades Cove, started offering guided hikes to the mountain in 1924. The trail he (and Thornborough's guide, Sam Cook) used largely followed the Bote Mountain Trail–Appalachian Trail route still in use today.[10]

In the years after the Great Smoky Mountains National Park was formed, trees began to reclaim much of the Smokies crest west of Clingmans Dome. Park strategy at present is to allow Thunderhead to return to its natural state. A narrow path is maintained across the top of the mountain for Appalachian Trail hikers.[11]

Access

The Bote Mountain Trail, with its trailhead on Little River Road, ascends seven miles (11 km) to the crest of the Smokies and intersects the Appalachian Trail at Spence Field. From Spence Field, it is approximately two miles (3 km) to the summit of Thunderhead. The Lead Cove Trail, also beginning on Little River Road (near Cades Cove), offers the shortest access to the summit by bypassing the first four miles (6 km) of the Bote Mountain Trail. From the Lead Cove trailhead, it is approximately 7 miles (11 km) to the summit of Thunderhead. The Anthony Creek Trail, rising out of the Cades Cove campground, also bypasses the first 4 miles (6.4 km) of the Bote Mountain Trail. From the Anthony Creek trailhead, it is approximately 7.5 miles (12 km) to the summit of Thunderhead.

While the main summit of Thunderhead is covered in foliage, Rocky Top offers a 360-degree view of the western Smokies.

References

- 1 2 3 "Thunderhead Mountain, North Carolina/Tennessee". Peakbagger.com. Retrieved 2019-07-22.

- ↑ "Thunderhead Mountain". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior. Retrieved 2019-07-22.

- ↑ "Tennessee county high points". Tennessee Landforms. Retrieved 2019-07-22.

- 1 2 Mason, Robert (1927). The Lure of the Great Smokies. Boston and New York: Houghton-Mifflen. p. 56. ISBN 978-1297505416.

- ↑ Thornborough, Laura (1942). Great Smoky Mountains. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press. p. 143. ISBN 978-0870490347.

- ↑ Moore, Harry (1988). A Roadside Guide to the Geology of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press. p. 32. ISBN 978-0870495588.

- ↑ Moore, Harry. 1988 pp. 26-27.

- ↑ Durwood, Dunn (1988). Cades Cove: The Life and Death of An Appalachian Community. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press. p. 43. ISBN 978-0870495595.

- 1 2 Brewer, Carson (1993). Great Smoky Mountains National Park. Portland, Ore: Graphic Arts Center Publishing. p. 21. ISBN 978-1558681262.

- ↑ Dunn, Durwood. 1988 p. 243.

- ↑ Pierce, Daniel (2000). The Great Smokies: From Natural Habitat to National Park. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press. p. 178. ISBN 978-1621901648.