The following is a timeline of the history of the city of Lviv, Ukraine.

Prior to 18th century

Historical affiliations

Kingdom of Galicia–Volhynia c. 1256–1340

Kingdom of Poland 1340–1569

Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth 1569–1772

Austrian Empire 1772–1867

Austro-Hungarian Empire 1867–1918

West Ukrainian People's Republic 1918

Poland 1918–1939

Soviet Union 1939–1941

Nazi Germany 1941–1944

Soviet Union 1944–1991

Ukraine 1991–present

| History of Ukraine |

|---|

.jpg.webp) |

|

|

- 1256 - Lviv mentioned in the Galician–Volhynian Chronicle.[1]

- 1272 - Leo I of Galicia relocates Galicia-Volhynia capital to Lviv from Halych (approximate date).[2]

- 1340 - Town taken by forces of Casimir III of Poland.[2][3]

- 1356 - City granted Magdeburg rights.[1]

- 1362 - High Castle rebuilt.

- 1363 - Armenian church built.[3]

- 1365 - Roman Catholic Diocese of Lwów established.[4]

- 1370 - Latin Cathedral construction begins (approximate date).

- 1387 - 27 September: Petru II of Moldavia paid homage to Polish King Władysław II Jagiełło and Queen Jadwiga of Poland making Moldavia a vassal principality of the Kingdom of Poland.[5]

- 1412 - Catholic see established.[6][3]

- 1434 - City becomes capital of the Polish Ruthenian Voivodeship.[1][3]

- 1480 - Latin Cathedral construction completed.[3]

- 1527 - Lviv fire of 1527.[2]

- 1550 - Church of St. Onuphrius built.

- 1556 - Arsenal built.

- 1580 - Korniakt Palace built on Market Square.

- 1582 - Karaite synagogue built.[7]

- 1586 - Ukrainian Lviv Dormition Brotherhood established.[1]

- 1589 - Bandinelli Palace built on Market Square.

- 1593 - Printing press in operation.[8]

- 1596 - Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church founded.[3]

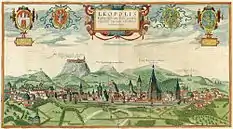

17th-century view of the city

- 1609 - Golden Rose Synagogue opens.[7]

- 1618 - Hlyniany Gate built.

- 1626 - City becomes seat of Armenian bishopric.[9]

- 1629 - Dormition Church built.

- 1630 - Bernardine Church and Monastery and Church of St. Mary Magdalene consecrated.

- 1648 - City besieged by Cossacks.[10][3]

- 1655 - City besieged by Cossacks again.[3]

- 1656 - Lwów Oath.

- 1661 - Jesuit Lviv University founded.

- 1672 - Siege of Lviv by Turks.[10][3]

- 1675 - Battle of Lwów (1675).

18th–19th centuries

- 1704 - City besieged by forces of Charles XII of Sweden.[11][3]

- 1762 - Greek Catholic St. George's Cathedral built.

- 1771 - 4th Infantry Regiment of the Polish Crown Army stationed in Lwów.[12]

- 1772 - City annexed by Austria in the First Partition of Poland and made the capital of the newly formed Austrian Galicia[6] under the Germanized name Lemberg.

- 1776 - Population: 29,500.[2]

- 1784

- Secular University established.[11]

- Brygidki prison in use.

- 1787 - Lychakiv Cemetery established.

- 1788 - Stauropegion Institute founded.

- 1809

- May: 19th Polish Uhlan Regiment formed in Lwów.[13]

- 27 May-19 June: City taken by forces of Józef Poniatowski.[11][14]

- 1810 - Gazeta Lwowska (1810-1939) newspaper begins publication.

- 1817 - Polish Ossolineum founded.[15]

- 1825 - German designated as official administrative language.[2]

- 1829 - Viennese Cafe in business.[16]

- 1835 - Town Hall[11] and Ivan Franko Park gazebo built.[3]

- 1842 - Skarbek Theatre opens.

- 1844 - Technical Academy established.

- 1846 - Tempel Synagogue built.[17]

- 1848

- 2 November: City "bombarded by the Austrians."[10]

- Galician Dawn newspaper begins publication.

- 1850 - Chamber of Commerce founded.[18]

- 1853

- Ignacy Łukasiewicz invents kerosene lamp.

- Street lighting installed.

.jpg.webp)

Lwów in the 1860s

- 1863 - House of Invalids built.[17]

- 1867

- 7 February: Polish Gymnastic Society "Sokół" founded.

- Pravda newspaper begins publication.[1]

- 1868 - Prosvita society founded.[19]

- 1870

- 1873 - Shevchenko Scientific Society founded.[19]

- 1877 - Industrial exhibition held.[2]

- 1878 - Government House built.

- 1880 - Dilo newspaper begins publication.[19]

- 1881

- 1883 - Kurier Lwowski newspaper begins publication.

- 1890 - Population: 128,419.[20]

- 1892 - Lychakivskyi Park laid out.[21]

- 1893 - Grand Hotel built on Svobody Prospect.[21]

- 1894 - Galician Regional Exhibition held.[22]

- 1898

- John III Sobieski Monument erected in Svobody Prospect.[22]

- Literaturno-naukovyi vistnyk literary-scientific journal begins publication.[1]

- 1900

- Grand Theatre built.

- Population: 159,618.[3]

20th century

1900–1939

- 1901 - Hotel George opens.[23]

- 1903

- Lechia Lwów founded as the oldest Polish football club.

- Czarni Lwów founded as the second oldest Polish football club.

- 1904

- Railway station opens.

- Pogoń Lwów founded as the third oldest Polish football club.

- 1905 - Lwow Ecclesiastical Museum established.

- 1907 - Galician Music Society building constructed.[17]

- 1908

- 12 April: Politician Andrzej Kazimierz Potocki assassinated.[24]

- Polish History Museum, Lwów established.

- 1909 - Industry and Crafts College built.[17]

.jpg.webp)

Early 20th-century view of the Market Square

- 1911 - Church of Sts. Olha and Elizabeth built.

- 1913 - Magnus department store built on Hospital Street, Lviv.[17]

- 1914

- 1915

- 1918

- 1 November: City becomes capital of the Western Ukrainian People's Republic;[1] Battle of Lemberg (1918) begins.

- 21–23 November: Lwów pogrom (1918).

- November: Poles in power.

- 1920 - July–September: Battle of Lwów (1920).

- 1923 - City confirmed as part of Poland per Conference of Ambassadors.[1]

- 1924 - Polish Cemetery of the Defenders of Lwów established.

- 1925 - Beis Aharon V'Yisrael Synagogue built.

- 1929 - Members of the Lwów School of Mathematics, Stefan Banach and Hugo Steinhaus, establish Studia Mathematica journal.

- 1930 - Area of city: 66 square kilometers.[2]

- 1936

- April 14 - demonstration of unemployed people shot by Polish police. Killed 1 worker V. Kozak.

- April 16 - funeral of the killed worker Kozak, police fights against workers. 46 people killed.

- 1937 - Academy of Foreign Trade in Lwów established.

World War II (1939–1945)

Aerial view of the city center during World War II

- 1939

- 12 September: German forces attack the city. Battle of Lwów (1939) begins.[25][6]

- 18 September: Soviet forces join the German siege of the city.[25]

- 22 September: End of the Battle of Lwów.[6] Soviet occupation begins.

- September: Polish resistance movement established in the city.[26]

- The Soviets carried out deportations of captured Polish POWs to the USSR, mostly to Starobilsk.[25]

- October: Czerwony Sztandar Polish-language communist newspaper begins publication.

- November: City annexed into Soviet Ukraine, and made capital of the newly formed Lviv Oblast.[2]

- 1940

- General Michał Karaszewicz-Tokarzewski, leader of the Polish resistance, arrested by the NKVD.[27]

- April–May: Many Polish defenders of the city murdered in the Katyn massacre by the Soviets.[25]

- 19–20 November: The Soviets sentenced 14 leaders of the local branch of the Union of Armed Struggle Polish resistance organization to death.[26]

- Union of Soviet Architects branch and Ukrainian State Institute of Urban Planning branch organized.[28]

- 1941

- 24 February: 13 leaders of the Union of Armed Struggle executed by the Soviets following their sentencing in November 1940.[26]

- 22–30 June: Battle of Lwów (1941).

- 30 June: German occupation begins.[6]

- June–July: Lviv pogroms (1941).

- July: Massacre of Lwów professors.

- 26 July: Execution of pre-war Prime Minister of Poland Kazimierz Bartel by the Germans.

- 1 August: City made capital of the newly formed District of Galicia within the General Government of occupied Poland.

- 3 August: Stalag 328 prisoner-of-war camp established by the Germans.[29]

- September: Janowska concentration camp begins operating.

- 8 November: Lwów Ghetto is established.

- 1942 - Local branch of the Żegota underground Polish resistance organization established to rescue Jews from the Holocaust.[30]

- 1943

- 1944

- 1 February: Stalag 328 POW camp converted into the Oflag 76 POW camp for officers.[31]

- 9 May: Oflag 76 POW camp dissolved.[31]

- 23–27 July: Polish Lwów Uprising against German occupation.

- 27 July: German occupation ends; city re-occupied by the Soviet Union.[6]

- December: Expulsion of Poles from Lviv begins.[32]

- Central State Historical Archive of the Ukrainian SSR in Lviv established.[33]

- 1945 - City annexed from Poland by the Soviet Union, and renamed to Lviv.

1945–2000

- 1945 – Lviv Bus Factory built.

- 1952

- 1957 - Ukrzakhidproektrestavratsia Institute established.[34]

- 1958 - Polish People's Theatre established.[32]

- 1963

- Football Club Karpaty Lviv formed.

- Ukraina Stadium opens.

- 1965 - Population: 496,000.[35]

- 1966 - Pharmacy Museum opens.

- 1970

- 1979 - Population: 665,065.[37]

- 1985 - Population: 742,000.[38]

- 1987

- 1989

- Dead Rooster musical group formed.

- Population: 786,903.[37]

- 1990

- Vyvykh festival festival begins.

- Vasyl Shpitser becomes mayor.

- Gazeta Lwowska Polish-language magazine begins publication.

- Russian Cultural Centre opens.

- Area of city: 90 square kilometers.[2]

- 1991

- City becomes part of independent Ukraine.[2]

- Chervona Ruta (festival) of music held.

- Lviv Physics and Mathematics Lyceum founded.

- 1992

- 1993 - Znesinnia Regional Landscape Park established.

- 1994 - Vasyl Kuybida becomes mayor.

- 1996 - Lviv Suburban railway station built.

- 1998 - Old Town (Lviv) designated an UNESCO World Heritage Site.

21st century

- 2001 - Population: 725,202.[37]

- 2002

- 27 July: Air show disaster occurs near city.

- Ukrainian Catholic University established.[34]

- 2004 - Center for Urban History of East Central Europe founded.

- 2006 - Andriy Sadovyi becomes mayor.

.jpg.webp)

Fire at a fuel depot after Russian shelling in 2022

- 2008 - Etnovyr folklore festival and Wiz-Art film festival begin.

- 2009 - Pogoń Lwów football club re-established.

- 2011 - Arena Lviv opens.

- 2012 - June: Some UEFA Euro 2012 football games played in Lviv.

- 2014

- January: 2014 Euromaidan regional state administration occupation.[41]

- February: 2014 Ukrainian revolution.

- 2018 - Population: 720,105 (estimate).[42]

- 2022 - Russian missile attack on the city.

See also

- History of Lviv

- Other names of Lviv (Lemberg, Lwów, etc.)

- List of mayors of Lviv

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Ivan Katchanovski; et al. (2013). "Lviv". Historical Dictionary of Ukraine (2nd ed.). Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-7847-1.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Hrytsak 2000.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Britannica 1910.

- ↑ "Chronology of Catholic Dioceses: Ukraine". Norway: Oslo katolske bispedømme (Oslo Catholic Diocese). Retrieved 28 February 2015.

- ↑ "Kalendarz dat: 1387". Dzieje.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 10 July 2022.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "Lvov", Webster's Geographical Dictionary, USA: G. & C. Merriam Co., 1960, p. 643, OL 5812502M

- 1 2 "L'viv". Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe. New York: Yivo Institute for Jewish Research. Archived from the original on 9 October 2014.

- ↑ Henri Bouchot (1890). "Topographical index of the principal towns where early printing presses were established". In H. Grevel (ed.). The book: its printers, illustrators, and binders, from Gutenberg to the present time. H. Grevel & Co.

- 1 2 3 George Lerski (1996). "Lvov". Historical Dictionary of Poland, 966-1945. Greenwood. ISBN 978-0-313-03456-5.

- 1 2 3 4 Ripley 1879.

- 1 2 3 4 Townsend 1877.

- ↑ Gembarzewski, Bronisław (1925). Rodowody pułków polskich i oddziałów równorzędnych od r. 1717 do r. 1831 (in Polish). Warszawa: Towarzystwo Wiedzy Wojskowej. p. 27.

- ↑ Gembarzewski, p. 62

- ↑ Die Stadt Lemberg im Jahre 1809 [Lemberg in 1809] (in German). Lviv: Schnellpresse des Stauropigian-Instituts. 1862.

- ↑ Paul Robert Magocsi (2002). Historical Atlas of Central Europe. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-0-8020-8486-6.

- ↑ Larry Wolff (2012). The Idea of Galicia: History and Fantasy in Habsburg Political Culture. Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-7429-1.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Purchla 2000.

- ↑ "Ukraine: Directory". Europa World Year Book. Taylor & Francis. 2004. p. 4319+. ISBN 978-1-85743-255-8.

- 1 2 3 Ivan Katchanovski; et al. (2013). "Chronology". Historical Dictionary of Ukraine (2nd ed.). Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-7847-1.

- ↑ Chambers 1901.

- 1 2 3 "Lviv Interactive". Lviv: Center for Urban History of East Central Europe. Retrieved 28 February 2015.

- 1 2 Prokopovych 2009.

- ↑ "Lviv's, and a Family's, Stories in Architecture", New York Times, 17 October 2013

- ↑ Benjamin Vincent (1910), "Austrian Galicia", Haydn's Dictionary of Dates (25th ed.), London: Ward, Lock & Co., hdl:2027/loc.ark:/13960/t89g6g776 – via Hathi Trust

- 1 2 3 4 Agresja sowiecka na Polskę i okupacja wschodnich terenów Rzeczypospolitej 1939–1941 (in Polish). Białystok-Warszawa: IPN. 2019. pp. 8–9. ISBN 978-83-8098-706-7.

- 1 2 3 Agresja sowiecka na Polskę i okupacja wschodnich terenów Rzeczypospolitej 1939–1941, p. 15

- ↑ Agresja sowiecka na Polskę i okupacja wschodnich terenów Rzeczypospolitej 1939–1941, p. 38

- 1 2 3 Tscherkes 2000.

- 1 2 3 Megargee, Geoffrey P.; Overmans, Rüdiger; Vogt, Wolfgang (2022). The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos 1933–1945. Volume IV. Indiana University Press, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. p. 324. ISBN 978-0-253-06089-1.

- ↑ Datner, Szymon (1968). Las sprawiedliwych (in Polish). Warszawa: Książka i Wiedza. p. 69.

- 1 2 Megargee, Geoffrey P.; Overmans, Rüdiger; Vogt, Wolfgang (2022). The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos 1933–1945. Volume IV. Indiana University Press, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. p. 225. ISBN 978-0-253-06089-1.

- 1 2 3 Risch 2011.

- ↑ Patricia Kennedy Grimsted (1988). "Repositories in Lviv". Ukraine and Moldavia. Princeton University Press. p. 425. ISBN 978-1-4008-5982-5.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - 1 2 3 "Links". Lviv: Center for Urban History of East Central Europe. Retrieved 28 February 2015.

- ↑ "Population of capital cities and cities of 100,000 and more inhabitants". Demographic Yearbook 1965. New York: Statistical Office of the United Nations. 1966.

Lvov

- 1 2 Bohdan Yasinsky (ed.). "Place of Publication Index: Lviv". Independent Press in Ukraine, 1988-1992. USA: Library of Congress. Retrieved 28 February 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 Lozinski 2005.

- ↑ United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Statistical Office (1987). "Population of capital cities and cities of 100,000 and more inhabitants". 1985 Demographic Yearbook. New York. pp. 247–289.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ Kenney 2000.

- ↑ Alexandra Hrycak (1997). "The Coming of "Chrysler Imperial": Ukrainian Youth and Rituals of Resistance". Harvard Ukrainian Studies. 21 (1/2): 63–91. JSTOR 41036642.

- ↑ "A Ukraine City Spins Beyond the Government's Reach", New York Times, 15 February 2014

- ↑ "Table 8 - Population of capital cities and cities of 100,000 or more inhabitants", Demographic Yearbook – 2020, United Nations

- This article incorporates information from the Ukrainian Wikipedia, Polish Wikipedia, German Wikipedia, and Russian Wikipedia.

Bibliography

- Published in the 19th century

- Abraham Rees (1819), "Lemberg", The Cyclopaedia, London: Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme & Brown, hdl:2027/mdp.39015068382327

- John Ramsay McCulloch (1851). "Lemberg". A Dictionary, Geographical, Statistical, and Historical. Longman, Brown, Green and Longmans.

- Charles Knight, ed. (1867). "Lemberg". Geography. Vol. 2. London. hdl:2027/nyp.33433000064802.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help)CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - David Kay (1880), "Principal Towns: Lemberg", Austria-Hungary, Foreign Countries and British Colonies, London: Sampson Low, Marston, Searle, & Rivington, hdl:2027/mdp.39015030647005

- George Henry Townsend (1877), "Lemberg", Manual of Dates (5th ed.), London: Frederick Warne & Co., hdl:2027/wu.89097349427

- George Ripley; Charles A. Dana, eds. (1879). "Lemberg". American Cyclopedia (2nd ed.). New York: D. Appleton and Company. hdl:2027/hvd.hn585q.

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 14 (9th ed.). 1882. p. 435.

- Norddeutscher Lloyd (1896), "Austria: Lemberg", Guide through Germany, Austria-Hungary, Italy, Switzerland, France, Belgium, Holland and England, Berlin: J. Reichmann & Cantor, OCLC 8395555

- Published in the 20th century

- "Lemberg", Chambers's Encyclopaedia, London: W. & R. Chambers, 1901, hdl:2027/uc2.ark:/13960/t7zk5ms79

- "Lemberg". Handbook for Travellers in South Germany and Austria (15th ed.). London: J. Murray. 1903.

- A.S. Waldstein (1907), "Lemberg", Jewish Encyclopedia, vol. 7, New York, hdl:2027/osu.32435029752888

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 16 (11th ed.). 1910. pp. 409–410.

- S. Vailhe (1910). "Lemberg". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - "Lemberg". Austria-Hungary (11th ed.). Leipzig: Karl Baedeker. 1911.

- Bohdan Janusz (1922). Przewodnik po Lwowie [Guide to Lwow] (in Polish). Lviv: Wszechświat.

- Rosa Bailly (1956), A City Fights for Freedom: The Rising of Lwów in 1918-1919, London: Publishing Committee Leopolis

- George G. Grabowicz (2000). "Mythologizing Lviv/Lwów: Echoes of Presence and Absence". Harvard Ukrainian Studies. 24: 313–342. JSTOR 41036821.

- Yaroslav Hrytsak (2000). "Lviv: A Multicultural History through the Centuries". Harvard Ukrainian Studies. 24: 47–73. JSTOR 41036810.

- Padraic Kenney (2000). "Lviv's Central European Renaissance, 1987–1990". Harvard Ukrainian Studies. 24: 303–312. JSTOR 41036820.

- Jacek Purchla (2000). "Patterns of Influence: Lviv and Vienna in the Mirror of Architecture". Harvard Ukrainian Studies. 24: 131–147. JSTOR 41036813.

- Bohdan Tscherkes; Nicholas Sawicki (2000). "Stalinist Visions for the Urban Transformation of Lviv, 1939–1955". Harvard Ukrainian Studies. 24: 205–222. JSTOR 41036816.

- Published in 21st century

- Роман Лозинський (Roman Lozinski) (2005), Етнічний склад населення Львова (у контексті суспільного розвитку Галичини) [Ethnic composition of the city (in the context of social development Galicia)] (PDF) (in Ukrainian), Lviv: Ivan Franko National University of L'viv)

- Heidi Hein (2006). Christian Emden; et al. (eds.). Idea of Lviv as a Bulwark against the East. Peter Lang. p. 321. ISBN 978-3-03910-533-5.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Markian Prokopovych (2009). Habsburg Lemberg: Architecture, Public Space, and Politics in the Galician Capital, 1772-1914. Purdue University Press. ISBN 978-1-55753-510-8.

- William Jay Risch (2011). Ukrainian West: Culture and the Fate of Empire in Soviet Lviv. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-05001-3.

- Tarik Cyril Amar (2015). The Paradox of Ukrainian Lviv. A Borderland City between Nazis, Stalinists, and Nationalists. Cornell University. ISBN 978-0-8014-5391-5.

External links

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Lviv.

- Europeana. Items related to Lviv, various dates.

- Digital Public Library of America. Items related to Lviv, various dates

This article is issued from Wikipedia. The text is licensed under Creative Commons - Attribution - Sharealike. Additional terms may apply for the media files.