The following is a timeline of the history of the city of Poznań, Poland.

Prior to 19th century

| History of Poland |

|---|

|

|

|

- 968 – Roman Catholic Diocese of Poznań established.

- 10th century – Poznań Cathedral built.

- 1038

- City taken by forces of Bretislaus I, Duke of Bohemia.

- 11th C. – St. Michael church built.

- 1249 – Castle construction begins (approximate date).

- 1253

- Town gains Magdeburg rights.

- Town Hall built.[1]

- 1296

- Wielkopolska Chronicle written.[2]

- 1320 – Town becomes capital of the Poznań Voivodeship.

- 1341 – 29 September: Coronation of Adelaide of Hesse in Poznań Cathedral.

- 1493 – Grand Master of the Teutonic Order Johann von Tiefen paid homage to King of Poland John I Albert.[3]

- 1518 – Lubrański Academy established.

- 1534 – Waga Miejska (weighing house) built.

- 1536 – Fire.[2]

- 1551 – Flood.[2]

- 1557 – Poznań native Josephus Struthius, renowned Polish professor of medicine and court physician to Polish kings, became mayor after gaining international recognition for his depiction of the human pulse and its use for diagnostic purposes.

- 1560 – Town Hall rebuilt on Market Square.

- 1563 – Cloth Hall rebuilt.

- 1573 – Jesuit College established.[2]

- 1585 – First acquisition of citizenship in the city by a Scot (see also Scots in Poland).[4]

- 1611 – Origins of University in Poznań

- 1655

- Monastery of Oratory of Saint Philip Neri established.[5]

- City taken by Swedish forces.

- 1677 – Jesuit printing press in operation.[6]

- 1701 – Baroque Poznań Fara completed.

- 1704 – 9 August: Battle of Poznań during the Swedish invasion of Poland (1701–1706).

- 1710 – Plague.[2]

- 1736 – Flood.[2]

- 1763 – Prince Frederick Mounted Regiment of the Polish Crown Army stationed in Poznań.[7]

- 1775 – 1st Polish Infantry Regiment of the Polish Crown Army stationed in Poznań.[8]

- 1776 – Baroque Działyński Palace completed.

- 1777 – New Baroque Monastery of Oratory of Saint Philip Neri completed.[5]

- 1786 – 7th Polish Infantry Regiment stationed in Poznań.[9]

- 1787 – Odwach (guardhouse) on Market Square rebuilt.

- 1790 – 2nd Polish Artillery Brigade formed and garrisoned in Poznań.[10]

- 1792 – Polish 9th Infantry Regiment relocated from Warsaw to Poznań.[11]

- 1793

- City annexed by Prussia in the Second Partition of Poland and included within the newly formed province of South Prussia[12]

- City renamed "Posen."

- 1796 – Population: 16,124.

- 1800 – Śródka included within city limits.[5]

19th century

Entrence of Jan Henryk Dąbrowski to Poznań, painting of Jan Gładysz from 1809

- 1803 – Fire.[13]

- 1806

- Napoleon temporarily headquartered in city.[2]

- Polish 11th Infantry Regiment formed in Poznań.[14]

- 11 December: Treaty of Poznań signed.

- 1807 – Town becomes part of the Duchy of Warsaw.[12]

- 1815 – Town becomes part of Prussia again.[12]

- 1828

- Poznań Fortress construction begins.

- September: Visit of Fryderyk Chopin.[15]

- 1829 – Raczyński Library founded.[2][1]

- 1839 – Fort Winiary built.

- 1841 – Scientific Help Society for the Youth of the Grand Duchy of Poznań established.

- 1842 – Bazar Hotel founded.[2]

- 1846

- 1848

- Greater Poland uprising.

- 20 March: Polish National Committee founded.

- 11 April–9 May: Stay of Polish national poet Juliusz Słowacki in Poznań.[16]

- Szczecin–Poznań railway begins operating.[2]

- 1849 – 25 October: Publication of Fryderyk Chopin's first obituary, by poet Cyprian Norwid.[17]

- 1857

- Society of Friends of Learning established.[2]

- Museum of Polish and Slavic Antiquities (present-day National Museum) founded.

- Israelitische Brüdergemeinde synagogue built.[18]

- 1859 – First Adam Mickiewicz monument in partitioned Poland unveiled.[19]

- 1871 – Grand Duchy of Poznań abolished.[2]

- 1872 – Kurjer Poznański newspaper begins publication.

- 1873 – First biography of Fryderyk Chopin, by Marceli Szulc, published in Poznań.[17]

- 1875 – Polish Theatre[20] and Stare Zoo established.

- 1877 – Daughters of Charity of Saint Vincent de Paul expelled from Śródka.[5]

- 1879 – Poznań Central Station opens.[2]

- 1885

- 1886 – Prussian Settlement Commission established to coordinate German colonization in the Prussian Partition of Poland.

- 1891 – Richard Witting becomes mayor.

- 1893 – Daughters of Charity of Saint Vincent de Paul came back to Śródka.[5]

- 1895

- 1896 – Piotrowo and Berdychowo become part of city.[23]

- 1898 – Electric tramway begins operating.[2]

- 1900 – Górczyn, Jeżyce, Łazarz, and Wilda become part of city.[23]

20th century

1900–1939

- 1902 – Kaiser Wilhelm Library and Kaiser Friedrich Museum open.[21]

- 1903 – Royal Academy opens.[21]

- 1905 – Population: 136,808.[1]

- 1907 – Sołacz becomes part of city.[23]

- 1910

- Grand Theatre opens.

- Imperial Castle built.[1]

- Higher State School of Machinery founded.

- 1912 – Warta Poznań football club formed.

.jpg.webp)

First session of the Polish Provincial Sejm in Poznań (1918)

- 1918

- 3 December: The first session of the Polish Provincial Sejm (parliament) of the former Prussian Partition of Poland in Poznań.

- 27 December: Greater Poland Uprising (1918–19) against German rule begins.

- 28 December: City liberated by Polish insurgents.[24]

- 1919

- 6 January: Battle of Ławica, won by the Polish insurgents.[24]

- 4 April: Poznań University founded.

- Poznań Observatory founded.

- 27 October: Wielkopolskie Muzeum Wojska (military museum) opened.

- 1921 – Poznań Fair begins.[2]

- 1922 – Lutnia Dębiec football club formed.

- 1923 – Kronika Miasta Poznania (journal of city history) begins publication.

- 1925 – Dębiec, Główna, Komandoria, Rataje, Starołęka, Szeląg, and Winogrady become part of city.[23]

- 1927

- Poznań Radio Station established.[2]

- Ilustracja Poznańska begins publication.

- 15th Poznań Uhlan Regiment monument unveiled.[25]

- 1928 – Czarna Trzynastka Poznań wins its first and only Polish men's basketball championship.

- 1929 – Warta Poznań wins its first Polish football championship.

- 1930

- Tadeusz Kościuszko monument unveiled.[26]

- Population: 266,742.

- AZS Poznań wins its first Polish men's basketball championship.

- Association of Friends of the Sorbs established.[27]

- 1933 – Golęcin and Podolany become part of city.[23]

- 1935 – Lech Poznań wins its first Polish men's basketball championship.

World War II (1939–1945)

- 1939

- September: During the invasion of Poland at the beginning of World War II, near Słupca, the Germans bombed a train with Polish civilians fleeing the Wehrmacht from Poznań.[28]

- Poznań Nightingales (choir) secretly founded.

- 10 September: German troops invade Poznań, beginning of German occupation.[2]

- 10 September: Inhabitants of Poznań were among the victims of a massacre of Poles committed by German troops in Zdziechowa.[29]

- 12 September: The Einsatzkommando 1 and Einsatzgruppe VI paramilitary death squads entered the city to commit various crimes against the population.[30]

- September: Mass arrests of Poles by the occupying forces.[31]

- September: City made the headquarters of the central district of the Selbstschutz, which task was to commit atrocities against Poles during the German invasion of Poland.[32]

- September: Tajna Polska Organizacja Wojskowa (Secret Polish Military Organization) Polish resistance organization founded.[33]

- October: Infamous Fort VII concentration camp established by the Germans for imprisonment of Poles arrested in the city and region during the Intelligenzaktion.[34]

- October: Poznańska Organizacja Zbrojna (Poznań Military Organization), Narodowa Organizacja Bojowa (National Fighting Organization), Ojczyzna (Homeland) and Komitet Niesienia Pomocy (Relief Committee) Polish resistance organizations founded.[35]

- 16, 18, 20, 26, 28 October: Mass executions of 71 Polish prisoners in Fort VII. Among the victims were teachers, merchants, farmers, craftsmen, workers, doctors, lawyers, editors of Polish newspapers.[34]

- 22 October: First expulsion of Poles carried out by the German police.[36]

- November: Transit camp for Poles expelled from the city established by the occupiers.[37]

- 8, 18, 29 November: Further executions of over 30 Polish prisoners in Fort VII. Among the victims were merchants, craftsmen, editors of Polish newspapers.[38]

- 11 November: Special Staff for the Resettlement of Poles and Jews (Sonderstab für die Aussiedlung von Polen und Juden) founded by the Germans to coordinate the expulsion of Poles from the city and region, known as the Central Bureau for Resettlement (UWZ, Umwandererzentralstelle) since 1940.[39]

- 12–16 November: German police and SS massacred 60 Polish prisoners of the Fort VII concentration camp in the forest of Dębienko near Poznań.[40]

- December: Further executions of 14 Polish craftsmen in Fort VII.[38]

- The Germans massacred over 630 Polish prisoners of the Fort VII concentration camp, incl. 70 students of Poznań universities and colleges and 70 nuns, in the forest of Dopiewiec near Poznań.[38]

- Ernst Damzog, former commander of the Einsatzgruppe V, was appointed the police inspector for both Sicherheitspolizei and Sicherheitsdienst in German-occupied Poznań.[41]

- Tadeusz Kościuszko and 15th Poznań Uhlan Regiment monuments destroyed by the Germans.[25][26]

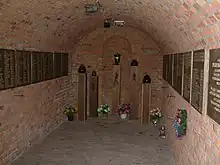

Bunker no. 16 in Fort VII, used by the German occupiers as an improvised gas chamber

- 1940

- January: Further executions of 67 Poles in Fort VII. Among the victims were teachers, local officials, engineers, artists, priests, professors and merchants.[38]

- 27 January, 20 February, 5 March, 25 April: The Germans massacred over 700 Polish prisoners of the Fort VII concentration camp, incl. 120 women, in the forest of Dębienko.[40]

- February: The regional branch of the Union of Armed Struggle begins to organize.[42]

- February, April and May: Further executions of 21 Poles in Fort VII.[38]

- March: Several Polish resistance organizations merged into the Wojskowa Organizacja Ziem Zachodnich (Military Organization of the Western Lands).[43]

- Early 1940: The Germans massacred over 2,000 Polish prisoners of the Fort VII concentration camp in the forest of Dopiewiec.[38]

- Spring: Polska Niepodległa (Independent Poland) resistance organization starts operating in Poznań.[43]

- April: First arrests of members of Wojskowa Organizacja Ziem Zachodnich carried out by the Germans.[33]

- 20 April: Over 100 Poles were arrested by the Germans in the city in just one day.[44]

- June: Bureau of the Government Delegation for Poland for Polish territories annexed by Germany founded.[45]

- 1 August: Stalag XXI-D prisoner-of-war camp for Allied POWs established by the occupiers.[46]

- Autumn: Regional branch of the Bataliony Chłopskie resistance organization established.[47]

- Autumn: Wojskowa Organizacja Ziem Zachodnich crushed by the Germans. Surviving members joined the Union of Armed Struggle.[33]

- Adam Mickiewicz monument destroyed by the Germans.[19]

Reichsmarine rally in German-occupied Poznań in April 1941

- 1941

- The German labor office in Poznań demanded that children as young as 12 register for work, but it is known that even ten-year-old children were forced to work.[48]

- Spring: Komitet Niesienia Pomocy joined the Union of Armed Struggle.[33]

- May: The Polish resistance movement facilitated escapes of British prisoners of war from the Stalag XXI-D POW camp.[49]

- 1942: Mass arrests of members of the Komitet Niesienia Pomocy resistance organization carried out by the Germans.[33]

- 1943

- 20–21 February: A flying unit of the Union of Armed Struggle and Home Army carried out a spectacular operation to burn down Wehrmacht warehouses in the local river port.[50]

- February: First Soviet POWs brought by the Germans to Stalag XXI-D.[46]

- 14 September: Kidnapped Polish children from Poznań were deported to a camp for Polish children in Łódź, which was nicknamed "little Auschwitz" due to its conditions.[51]

- October: Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler delivers Posen speeches.

- Lake Rusałka created.

- December: First Italian POWs brought by the Germans to Stalag XXI-D.[46]

- 1944

- April: Fort VII concentration camp dissolved.

- Aerial bombing by U.S. forces.[2]

- 1945

- January–February: Battle of Poznań.

- February: Stalag XXI-D POW camp dissolved.[46]

- End of German occupation.

1945–1990s

Burial of Polish composer Feliks Nowowiejski in 1946

- 1945 – Głos Wielkopolski newspaper begins publication.[22]

- 1947 – Poznań Philharmonic founded.

- 1949 – 1572 Posnania asteroid discovered at the Poznań Observatory (named after the city).[52]

- 1950 – Population: 320,700.

- 1952 – Lake Malta created.

- 1954 – City administration divided into five dzielnicas: Stare Miasto, Nowe Miasto, Jeżyce, Grunwald, and Wilda.

- 1956

- Poznań 1956 protests.[53][54]

- Poznań Cathedral rebuilt.

- Mass raising of funds, food, medical supplies and equipment, and blood donation for the Poznań-inspired Hungarian Revolution of 1956.[55]

- 29 October: First two airplanes with aid for the Hungarians depart Poznań.[55]

- 30 October: Manifestation of support for the Hungarian Revolution of 1956.[55]

- 1963

- Piątkowo transmitter erected.

- Wielkopolskie Muzeum Wojskowe (military museum) opens.

- 1964 – Teatr Osmego Dnia (theatre group) founded.[20]

- 1966 – Sister city partnership signed between Poznań and Brno.[56]

- 1967 – Rebuilt Tadeusz Kościuszko monument unveiled.[26]

- 1970 – Park Cytadela established.

Saint John's Fair in 1978

- 1971

- Grunwald Poznań wins its first Polish handball championship.

- Polonia Poznań wins its first Polish rugby championship.

- 1973 – Polish Dance Theatre founded.[20]

- 1974

- Hala Arena opens.

- Zoo established.

- Population: 502,800.[57]

- 1979 – Sister city partnership signed between Poznań and Jyväskylä, Finland.[58]

- 1980 – Municipal Stadium opens.

- 1982

- Rebuilt 15th Poznań Uhlan Regiment monument unveiled.[25]

- Poznań Army monument unveiled.[59]

- 1983

- Lech Poznań wins its first Polish football championship.

- June: Visit of Pope John Paul II.[60]

- 1987 – Kiekrz, Morasko, and Radojewo become part of city.

- 1989 – Lech Poznań wins its tenth Polish men's basketball championship.

- 1990

- Wojciech Szczęsny Kaczmarek becomes mayor.[61]

- Population: 590,049.

- 1991

- Gazeta Poznańska newspaper begins publication.[22]

- 6 April: Sister city partnership signed between Poznań and Toledo, Ohio, United States.[62]

Pope John Paul II in Poznań, 1997

- 1997

- Sekcja Rowerzystów Miejskich (bicycle advocacy group) active.

- Poznański Szybki Tramwaj (tramway) opens.

- June: Visit of Pope John Paul II.[60]

- 1998 – Ryszard Grobelny becomes mayor.[61]

- 1999

- City becomes capital of Greater Poland Voivodeship.

- Monument to victims of the Katyn massacre and Soviet deportations to Siberia unveiled.[63]

- 2000 – Polish 31st Air Base established near city.

21st century

- 2007

- Bishop Jordan Bridge opens to Ostrów Tumski.

- Monument to Marian Rejewski, Jerzy Różycki and Henryk Zygalski, cryptologist who deciphered the Enigma machine, unveiled.[64]

- Polish Underground State monument unveiled.[65]

- 2008

- 23 January: Sister city partnership signed between Poznań and Győr, Hungary.[66]

- Animator International Animated Film Festival begins.

- December: City hosts 2008 United Nations Climate Change Conference.

- 2009

- 6 July: Sister city partnership signed between Poznań and Kutaisi, Georgia.[67]

- September: Poznań co-hosts the EuroBasket 2009.

- 2010 – Population: 551,627.

- 2011

- City administration divided into 42 osiedles (neighbourhoods).

- March: Honorary Consulate of Croatia opened (see also Croatia–Poland relations).[68]

- May: Honorary Consulate of Morocco established (see also Morocco–Poland relations).[69]

- August: Transatlantyk – Poznań International Film and Music Festival begins.

- Non-commissioned Officer School of the Land Forces in Poznań founded.

Poznań Old Town in 2012

- 2012 – Poznań co-hosts the UEFA Euro 2012.

- 2013

- February: Honorary Consulate of Guatemala opened.[70]

- August: Homeless World Cup football contest held.[71]

- 2014

- January: Honorary Consulate of Luxembourg opened (see also Luxembourg–Poland relations).[72]

- April: Poznań Croissant Museum established.

- 2015

- August: Medieval treasure, including 350 coins and 8,000 fragments of clay vessels, discovered during archaeological excavations in the Old Town.[73]

- Ignacy Jan Paderewski monument unveiled.[74]

- 2017 – Sister city partnership signed between Poznań and Bologna, Italy.[75]

- 2021

- 14 July: Honorary Consulate of Estonia opened (see also Estonia–Poland relations).[76]

- June: Bohdan Smoleń monument unveiled.[77]

- 25 September: Enigma Cipher Centre established.

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Britannica 1910.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 Łęcki 1997.

- ↑ "Kalendarz dat: 1493". Dzieje.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 16 July 2022.

- ↑ Feduszka, Jacek (2009). "Szkoci i Anglicy w Zamościu w XVI-XVIII wieku". Czasy Nowożytne (in Polish). Vol. 22. Zarząd Główny Polskiego Towarzystwa Historycznego. p. 52. ISSN 1428-8982.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Anna Dyszkant. "Dom Kongregacji Oratorium św. Filipa Neri". Zabytek.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 16 July 2022.

- ↑ "Drukarnia Kolegium Towarzystwa Jezusowego w Poznaniu 1677-1773". Wielkopolska Biblioteka Cyfrowa. April 1997. Retrieved 10 April 2019.

- ↑ Gembarzewski, Bronisław (1925). Rodowody pułków polskich i oddziałów równorzędnych od r. 1717 do r. 1831 (in Polish). Warszawa: Towarzystwo Wiedzy Wojskowej. p. 20.

- ↑ Gembarzewski, p. 26

- ↑ Gembarzewski, p. 28

- ↑ Górski, Konstanty (1902). Historya Artylerii Polskiej (in Polish). Warszawa. p. 193.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ Gembarzewski, p. 29

- 1 2 3 Haydn 1910.

- 1 2 Townsend 1867.

- ↑ Gembarzewski, p. 56

- ↑ Plenzler, Anna (2012). Śladami Fryderyka Chopina po Wielkopolsce (in Polish). Poznań: Wielkopolska Organizacja Turystyczna. p. 2. ISBN 978-83-61454-99-1.

- ↑ Hahn, Wiktor (1948). "Juliusz Słowacki w 1848 r.". Sobótka (in Polish). Wrocław. III (I): 85.

- 1 2 Plenzler, p. 4

- ↑ "Poznań". Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe. Yivo Institute for Jewish Research. Archived from the original on 2014-10-15.

- 1 2 "Adama Mickiewicza". Poznań.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 16 July 2022.

- 1 2 3 Don Rubin, ed. (2001). "Poland". World Encyclopedia of Contemporary Theatre. Vol. 1: Europe. Routledge. p. 634+. ISBN 9780415251570.

- 1 2 3 Königliche Museen zu Berlin (1904). Kunsthandbuch für Deutschland (in German) (6th ed.). Georg Reimer.

- 1 2 3 Europa World Year Book 2004. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 1857432533.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Statystyczna Karta Historii Poznania" (PDF). Główny Urząd Statystyczny. June 2008. Retrieved 10 April 2019.

- 1 2 Plasota, Kazimierz (1929). Zarys historji wojennej 68-go Pułku Piechoty (in Polish). Warszawa. p. 5.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - 1 2 3 "15. Pułku Ułanów Poznańskich". Poznań.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 16 July 2022.

- 1 2 3 "Tadeusza Kościuszki". Poznań.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 16 July 2022.

- ↑ Lewaszkiewicz, Tadeusz (2015). "Zarys dziejów sorabistyki i zainteresowań Łużycami w Wielkopolsce". In Kurowska, Hanna (ed.). Kapitał społeczno-polityczny Serbołużyczan (in Polish). Zielona Góra: Uniwersytet Zielonogórski. p. 92.

- ↑ Wardzyńska, Maria (2009). Był rok 1939. Operacja niemieckiej policji bezpieczeństwa w Polsce. Intelligenzaktion (in Polish). Warszawa: IPN. p. 89.

- ↑ Wardzyńska (2009), p. 91

- ↑ Wardzyńska (2009), p. 113

- ↑ Wardzyńska (2009), p. 116

- ↑ Wardzyńska (2009), p. 63

- 1 2 3 4 5 Pietrowicz 2011, p. 32.

- 1 2 Wardzyńska (2009), p. 190

- ↑ Pietrowicz 2011, pp. 28–29, 31–32.

- ↑ Wardzyńska, Maria (2017). Wysiedlenia ludności polskiej z okupowanych ziem polskich włączonych do III Rzeszy w latach 1939-1945 (in Polish). Warszawa: IPN. p. 144. ISBN 978-83-8098-174-4.

- ↑ Wardzyńska (2017), p. 145

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Wardzyńska (2009), p. 191

- ↑ Wardzyńska (2017), p. 35

- 1 2 Wardzyńska (2009), p. 192

- ↑ Wardzyńska (2009), p. 54

- ↑ Pietrowicz 2011, p. 36.

- 1 2 Pietrowicz 2011, p. 31.

- ↑ Wardzyńska (2009), p. 213

- ↑ Pietrowicz 2011, p. 34.

- 1 2 3 4 Megargee, Geoffrey P.; Overmans, Rüdiger; Vogt, Wolfgang (2022). The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos 1933–1945. Volume IV. Indiana University Press, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. p. 501. ISBN 978-0-253-06089-1.

- ↑ Pietrowicz 2011, p. 30.

- ↑ Kołakowski, Andrzej (2020). "Zbrodnia bez kary: eksterminacja dzieci polskich w okresie okupacji niemieckiej w latach 1939-1945". In Kostkiewicz, Janina (ed.). Zbrodnia bez kary... Eksterminacja i cierpienie polskich dzieci pod okupacją niemiecką (1939–1945) (in Polish). Kraków: Uniwersytet Jagielloński, Biblioteka Jagiellońska. p. 74.

- ↑ Aleksandra Pietrowicz. ""Dorsze" z Poznania". Przystanek Historia (in Polish). Retrieved 30 July 2022.

- ↑ Pietrowicz 2011, p. 25.

- ↑ Ledniowski, Krzysztof; Gola, Beata (2020). "Niemiecki obóz dla małoletnich Polaków w Łodzi przy ul. Przemysłowej". In Kostkiewicz, Janina (ed.). Zbrodnia bez kary... Eksterminacja i cierpienie polskich dzieci pod okupacją niemiecką (1939–1945) (in Polish). Kraków: Uniwersytet Jagielloński, Biblioteka Jagiellońska. pp. 147, 158.

- ↑ "1572 Posnania (1949 SC)". JPL Small-Body Database Browser. Retrieved 11 December 2023.

- ↑ "Poland Profile: Timeline". BBC News. Retrieved 30 November 2013.

- ↑ Bernard A. Cook, ed. (2013). "Chronology of Major Political Events". Europe Since 1945: An Encyclopedia. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-17939-7.

- 1 2 3 "W Poznaniu odsłonięto tablicę poświęconą pomocy dla Węgrów w 1956 roku". Dzieje.pl (in Polish). 23 October 2013. Retrieved 30 July 2022.

- ↑ "Brno (Republika Czeska)". Poznań.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 30 July 2022.

- ↑ United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Statistical Office (1976). "Population of capital city and cities of 100,000 and more inhabitants". Demographic Yearbook 1975. New York. pp. 253–279.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ "Jyväskylä (Finlandia)". Poznań.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 30 July 2022.

- ↑ "Armii 'Poznań'". Poznań.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 16 July 2022.

- 1 2 "Jan Paweł II w Poznaniu". Poznań.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 30 July 2022.

- 1 2 "Mayors of the City of Poznań". Poznań City Hall. Retrieved 28 November 2013.

- ↑ "Toledo (Ohio, USA)". Poznań.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 30 July 2022.

- ↑ "Ofiar Katynia i Sybiru". Poznań.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 16 July 2022.

- ↑ "Pogromców Enigmy". Poznań.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 16 July 2022.

- ↑ "Polskiego Państwa Podziemnego". Poznań.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 16 July 2022.

- ↑ "Gyor kolejnym miastem partnerskim Poznania". Poznań.pl (in Polish). 24 January 2008. Retrieved 30 July 2022.

- ↑ "Kutaisi". Poznań.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 30 July 2022.

- ↑ "Konsulat Chorwacji w Poznaniu". Radio Poznań (in Polish). 25 March 2011. Retrieved 16 July 2022.

- ↑ Anna Czuchra (20 May 2011). "Konsulat Honorowy Maroko". Wielkopolski Urząd Wojewódzki w Poznaniu (in Polish). Retrieved 11 December 2023.

- ↑ "Poznań: Otwarto Konsulat Honorowy Republiki Gwatemali". Głos Wielkopolski (in Polish). 28 February 2013. Retrieved 16 July 2022.

- ↑ Tina Rosenberg (October 9, 2014), "In This World Cup, the Goal is a Better Life", New York Times

- ↑ "Konsulat Luksemburga w Poznaniu już otwarty [ZDJĘCIA]". Głos Wielkopolski (in Polish). 30 January 2014. Retrieved 16 July 2022.

- ↑ "Skarby pod Starym Rynkiem w Poznaniu - m.in. monety i biżuteria". Dzieje.pl (in Polish). 16 August 2015. Retrieved 11 December 2023.

- ↑ "Pomnik Paderewskiego". Poznań.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 16 July 2022.

- ↑ "Bolonia nowym partnerem Poznania". Poznań.pl (in Polish). 5 December 2017. Retrieved 30 July 2022.

- ↑ "Otwarcie Konsulatu Honorowego Estonii w Poznaniu". warsaw.mfa.ee (in Polish). Retrieved 2 April 2022.

- ↑ "Poznań. Odsłonięto pomnik Bohdana Smolenia". Polsat News (in Polish). 12 June 2021. Retrieved 16 July 2022.

This article incorporates information from the Polish Wikipedia.

Bibliography

in English

- Published in 18th–19th centuries

- Richard Brookes (1786), "Posnania", The General Gazetteer (6th ed.), London: J.F.C. Rivington

- David Brewster, ed. (1830). "Posen". Edinburgh Encyclopædia. Edinburgh: William Blackwood.

- "Posen", Leigh's New Descriptive Road Book of Germany, London: Leigh and Son, 1837

- George Henry Townsend (1867), "Posen (Prussia)", Manual of Dates (2nd ed.), London: Frederick Warne & Co.

- "Posen". Handbook for North Germany. London: J. Murray. 1877.

- "Posen", Bradshaw's Illustrated Hand-book to Germany and Austria, London: W.J. Adams & Sons, 1898

- Published in 20th century

- "City of Posen", Jewish Encyclopedia, vol. 10, New York, 1907, hdl:2027/osu.32435029752854

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - "Posen", Northern Germany (15th ed.), Leipzig: Karl Baedeker, 1910, OCLC 78390379

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 22 (11th ed.). 1910.

- Benjamin Vincent (1910), "Posen", Haydn's Dictionary of Dates (25th ed.), London: Ward, Lock & Co.

- George Lerski (1996). "Poznan". Historical Dictionary of Poland, 966-1945. Greenwood. p. 472. ISBN 978-0-313-03456-5.

- Włodzimierz Łęcki (1997), Poznan: a City of History and Fairs, Poznan: GeoCenter Warszawa, ISBN 9788371502835

- Piotr Wróbel (1998). "Poznan". Historical Dictionary of Poland 1945-1996. Fitzroy Dearborn. p. 244. ISBN 978-1-135-92694-6.

in other languages

- Stadtbuch von Posen (in German), Posen: Eigenthum der Gesellschaft, 1892

- P. Krauss und E. Uetrecht, ed. (1913). "Posen". Meyers Deutscher Städteatlas [Meyer's Atlas of German Cities] (in German). Leipzig: Bibliographisches Institut.

- Pietrowicz, Aleksandra (2011). "Konspiracja wielkopolska 1939–1945". Biuletyn Instytutu Pamięci Narodowej (in Polish). No. 5–6 (126–127). IPN. ISSN 1641-9561.

External links

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Poznań.

- Links to fulltext city directories for Poznan via Wikisource

- Europeana. Items related to Poznań, various dates.

This article is issued from Wikipedia. The text is licensed under Creative Commons - Attribution - Sharealike. Additional terms may apply for the media files.