Death and Transfiguration (German: Tod und Verklärung), Op. 24, is a tone poem for orchestra by Richard Strauss. Strauss began composition in the late summer of 1888 and completed the work on 18 November 1889. The work is dedicated to the composer's friend Friedrich Rosch.

The music depicts the death of an artist. At Strauss's request, this was described in a poem by his friend Alexander Ritter as an interpretation of Death and Transfiguration, after it was composed.[1] As the man lies dying, thoughts of his life pass through his head: his childhood innocence, the struggles of his manhood, the attainment of his worldly goals; and at the end, he receives the longed-for transfiguration "from the infinite reaches of heaven".

Performance history

Strauss conducted the premiere on 21 June 1890 at the Eisenach Festival (on the same programme as the premiere of his Burleske in D minor for piano and orchestra). He also conducted this work for his first appearance in the United Kingdom, at the Wagner Concert with the Philharmonic Society on 15 June 1897 at the Queen's Hall in London.

Critical reaction

English music critic Ernest Newman described this as music to which one would not want to die or awaken. "It is too spectacular, too brilliantly lit, too full of pageantry of a crowd; whereas this is a journey one must make very quietly, and alone".[2]: 399

French critic Romain Rolland in his Musiciens d'aujourd'hui (1908) called the piece "one of the most moving works of Strauss, and that which is constructed with the noblest utility".[3]

Structure

There are four parts (with Ritter's poetic thoughts condensed):

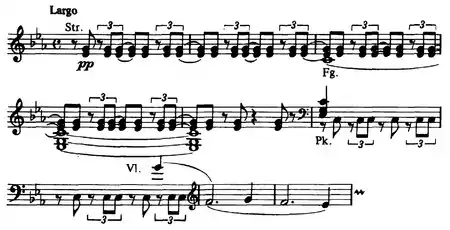

- Largo (The sick man, near death)

- Allegro molto agitato (The battle between life and death offers no respite to the man)

- Meno mosso (The dying man's life passes before him)

- Moderato (The sought-after transfiguration)

A typical performance lasts about 25 minutes.

Instrumentation

|

|

Quoted

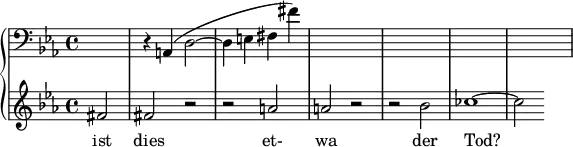

In one of his last compositions, "Im Abendrot" from the Four Last Songs, Strauss poignantly quotes the "transfiguration theme" from his tone poem of 60 years earlier, during and after the soprano's final line, "Ist dies etwa der Tod?" (Is this perhaps death?).

Just before his own death, he remarked that his music was absolutely correct, his feelings mirroring those of the artist depicted within; Strauss said to his daughter-in-law as he lay on his deathbed in 1949: "It's a funny thing, Alice, dying is just the way I composed it in Tod und Verklärung."[4]

Discography

Notes

- ↑ Bryan Gilliam: "Richard Strauss", Grove Music Online, ed. L. Macy (Accessed January 16, 2007), (subscription access)

- ↑ Newman, Ernest (1915). "The Music of Death". The Musical Times. Novello. 56: 399. Retrieved 2 February 2022.

- ↑ Quoted in Mason, Daniel Gregory (1918), Contemporary Composers, p. 84.

- ↑ Derrick Puffett's comments on DG disc 447 762-2

- ↑ Hunt J. A Gallic Trio – Charles Munch, Paul Paray, Pierre Monteux. John Hunt, 2003, 2009, p. 204.

- ↑ Strauss: Four Last Songs, etc, arkivmusic.com

Further reading

- Newman, Ernest. "The Music of Death" The Musical Times, July 1, 1915, pp. 398–399.

- "Herr Richard Strauss" The Musical Times, February 1, 1903, p. 115.

External links

- Video on YouTube, Symphony Orchestra of Flanders, conducted by Jan Latham-Koenig

- Tod und Verklärung: Scores at the International Music Score Library Project