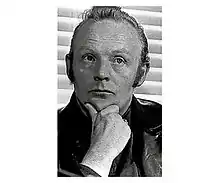

Tommy Herron | |

|---|---|

Tommy Herron | |

| Born | Thomas Herron 1938 Newcastle, County Down, Northern Ireland |

| Died | 14 September 1973 (aged 34–35) |

| Cause of death | One gunshot wound to the head |

| Resting place | Roselawn Cemetery, Belfast |

| Nationality | British |

| Organization | Ulster Defence Association |

| Title | East Belfast Brigadier |

| Term | 1971–1973 |

| Successor | Sammy McCormick |

| Political party | Vanguard Progressive Unionist Party |

| Spouse | Hilary Wilson |

| Children | 5 |

Tommy Herron (1938 – 14 September 1973) was a Northern Ireland loyalist and a leading member of the Ulster Defence Association (UDA) until his death in a fatal shooting. Herron controlled the UDA in East Belfast, one of its two earliest strongholds. From 1972, he was the organisation's vice-chairman and most prominent spokesperson,[1] and was the first person to receive a salary from the UDA.[2]

Early life

Herron was born in 1938 in Newcastle, County Down to a Protestant father and a Roman Catholic mother.[3] According to Martin Dillon, Herron was baptised in St Anthony's Catholic Church on Belfast's Woodstock Road as a baby.[4] Gusty Spence has suggested that Herron, like Shankill Butcher Lenny Murphy, took on the mantle of a "Super Prod", or individual who acts in an affectedly extreme Ulster Protestant loyalist way, to deflect any potential criticism of his Catholic roots.[4] Herron was a member of the Free Presbyterian Church of Ulster and regularly attended services at the Martyrs' Memorial Church, the group's headquarters on the Ravenhill Road in south-east Belfast.[5] He worked as a car salesman[1] in East Belfast[2] and was married to Hilary Wilson, by whom he had five children.

UDA leadership

Herron was a leading member of the UDA, which was the largest loyalist paramilitary organisation in Northern Ireland, from its formation and emerged at the group's top man in East Belfast. A thirteen-member Security Council was established in January 1972 with Herron a charter member of this group, although control lay in the west of city with Charles Harding Smith emerging as chairman of the new body.[6] Along with the likes of Billy Hull, Herron was one of a handful of UDA leaders to be invited to meetings with Secretary of State for Northern Ireland William Whitelaw after the suspension of the Parliament of Northern Ireland in March 1972.[7]

By this time Herron had come to see himself as the most powerful figure in the UDA and had begun to make statements on behalf of the movement unilaterally.[8] In September 1972, the British Army intervened to defend a Catholic area of Larne against loyalists. British Army vehicles ran down two civilians in East Belfast,[9] one of whom was believed to be a UDA member.[10] Under the name of the Ulster Citizen Army, Herron declared war on the British Army. He called this off after two days of gunfire due to a lack of support,[1][11][12] two more loyalists having been killed.

Herron's decision to go against the British Army, as brief as it was, as well as the looting and rioting that was taking place in Belfast under the direction of Herron and his close ally Jim Anderson as a reaction to the loyalists' deaths, saw both his stock and that of the Belfast UDA fall somewhat locally. Protestant clergymen petitioned the UDA to end the street violence whilst middle class Protestants, as well as politicians such as Roy Bradford, loudly condemned the attacks on the British Army, which traditionally enjoyed a high reputation amongst Northern Irish Protestants.[13] On 20 October 1972 Herron sent word to Colonel Sandy Boswell, the army commander in Belfast, that the trouble would end and it was to the relief of many that Herron left Belfast the following month, in the company of Billy Hull, to launch a tour of Canada promoting loyalism.[14]

Herron and Harding Smith

For much of 1972 Herron's main rival Charles Harding Smith, the leader of the West Belfast UDA, was absent from the scene after being arrested in England on gun-running charges. During his absence control on West Belfast went into the hands of Davy Fogel and his ally Ernie Elliott, both of whom had been influenced to varying degrees by left-wing rhetoric. Whilst Herron was not involved in initiatives by both men that saw dialogue with the Catholic Ex-Servicemen's Association of Ardoyne or the Official IRA he did accompany them to a meeting with representatives of the British & Irish Communist Organisation which, unusually for communist groups, followed a staunchly unionist position with regards Northern Ireland.[15]

Herron also garnered a reputation for his involvement in racketeering, something that Harding Smith had strongly condemned. In early 1973 an east Belfast publican was interviewed anonymously by The Sunday Times and he claimed that Herron would regularly send one of his men to the pub to ask for a contribution to the "UDA prisoners' welfare fund". The publican stated that he knew if he refused to contribute his windows would be smashed or the pub shot at, making the fund simply a protection racket.[16] Herron was apparently asking as much as £50 per week from each pub with shop owners expected to pay half that amount.[17]

After his return from England Harding Smith immediately clashed with Fogel but, somewhat surprisingly given their personal enmity, Herron sided with Harding Smith in the struggle. Herron summoned Fogel to his east Belfast office on 13 January 1973; when Fogel arrived, he was placed under arrest and detained for several hours. Herron told Fogel that he could only remain in charge of Woodvale if he agreed to accept Harding Smith's leadership in West Belfast as a whole. Fogel would leave Belfast altogether soon after this episode.[18] In February, Herron called for a general strike against the British Government's decision to introduce internment for suspected loyalist parliamilitaries, mirroring the existing internment for suspected republican paramilitaries. This led to a day's fighting on the streets.

Soon after the meeting with Fogel, and to many people's surprise, Herron called for "both sides" – loyalists and republicans – to stop assassinations, claiming that if they did not, they would face "the full wrath of the UDA". This temporarily halted killings in East Belfast.[9] Herron's decision to stop the random killings, as well as his meeting with communists and rumours about his Catholic background, led to criticism within the UDA and he was criticised strongly in the pages of Ulster Militant, one of the UDA's publications at the time.[19] Herron's position came under increasing pressure and, in an attempt to save face, he again threw his weight behind a new Harding Smith initiative. This time Harding Smith had decided to not only return to sectarian killings but to set up a group within the UDA, the Ulster Freedom Fighters (UFF), to be dedicated solely to this aim.[20] In the meantime Herron's leading hitman Albert Walker Baker had already been sent back on sectarian killing duty, launching a grenade attack on Catholic workers in East Belfast before shooting up a bus of Catholics in the Cherryvalley area.[21]

Fall from grace

In the summer of 1973 it was decided to choose a chairman of the UDA, after the resignation of joint chairman Jim Anderson, who shared his duties with Harding Smith but who had been in effect leader during the latter's absence, had left a power vacuum. Fears were raised that the issue might bring about the much feared Harding Smith and Herron feud, but in the end a compromise candidate, Andy Tyrie, was chosen in an effort to avert the war.[22] Herron remained in an unsafe position. On 15 June 1973, masked gunmen broke into his Braniel home and shot and killed his brother-in-law, 18-year-old Michael Wilson. Herron had been out of the house at the time. Michael Stone, a young UDA member who ran errands for Herron, had been near the house, and afterward asked Herron if he wanted him to kill a Provisional IRA (PIRA) member in retaliation. Herron told Stone "wrong side, kid", indicating that he believed the murder had been perpetrated by the rival faction of the UDA.[22]

According to Martin Dillon, the attack had been directed against Herron and had been ordered by Harding Smith, who hoped that it would be blamed on the PIRA.[23] Certainly Harding Smith had made it clear in the summer of 1973 that he wanted Herron and the rest of the criminal element out of the UDA.[24] Although Herron did not publicly speak about the killing, he placed information in the press that he believed it had been the work of rivals within the UDA, and also accused the UFF, and by extension Harding Smith, of being too close to the rival Ulster Volunteer Force in these same news stories.[25]

Herron was arrested in August 1973 under the terms of the Emergency Powers Act. A considerable sum of money, reported to be between £2000 and £9000, was found in his coat. Herron was released soon afterwards, but the story of the money was widely circulated in the press and it increased the growing discontent with his leadership in East Belfast, where many felt that he was increasingly using his role in the UDA to personally enrich himself.[26] Herron's personality and actions also fed into this animosity. He was known for swaggering around in the style of a mafia don, visibly carrying his legally held handgun, as well as for his short temper and sudden changes in mood.[27]

Politics

Despite narrowly missing death, Herron was also involved in a political campaign, as he was the candidate for the Vanguard Progressive Unionist Party (VPUP) candidate in East Belfast at the 1973 Northern Ireland Assembly election. One of the founding principles of the UDA had been that it should not be tied to a single political party, but Herron was an enthusiastic supporter of William Craig and when he established the VPUP, Herron declared as UDA spokesman that "we will be supporting the new party 100% and using every means within our power to ensure its success".[28]

Herron had argued that those who had joined or supported the UDA should be able to vote for its members, although in the event Herron struggled to convert his reputation as a loyalist hard case into that of a political figure.[29] Criticism came from Brian Faulkner and other moderate unionists, when on 10 June a UDA member exchanging gunfire with soldiers on the Beersbridge Road, East Belfast, shot and killed a Protestant bus driver.[28] Herron's campaign was again hit in June, when his East Belfast UDA headquarters were raided by the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) and two illegal guns and a quantity of ammunition were seized with two men arrested.[30] He took 2,480 votes but was not elected.[31]

Death

Herron was kidnapped in September 1973, and died by one gunshot to the head.[1][32] His body was found in a ditch near Drumbo, County Antrim. His death has often been ascribed to other members of the UDA, either in protest at his involvement in racketeering or as part of the ongoing feud,[33] while the UDA itself has claimed that the Special Air Service was responsible.[9][12]

Herron received a paramilitary funeral, presided over by Reverend Ian Paisley. It was attended by 25,000 mourners. He was buried at Roselawn Cemetery as a piper played "Amazing Grace".

Sammy McCormick took over Herron's East Belfast Brigade and this much more low-key figure was tasked with returning a sense of discipline to the increasingly chaotic brigade.[34]

References

- 1 2 3 4 Michael Farrell, Northern Ireland: The Orange State

- 1 2 Tommy Herron, MIPT Terrorism Knowledge Base

- ↑ Wood, Ian S., Crimes of Loyalty: A History of the UDA, Edinburgh University Press, 2006, p. 17

- 1 2 Martin Dillon, The Trigger Men, Mainstream, 2003, p. 184

- ↑ Dennis Cooke, Persecuting Zeal: A Portrait of Ian Paisley, Brandon Books, 1996, p. 184

- ↑ Henry McDonald & Jim Cusack, UDA: Inside the Heart of Loyalist Terror, Penguin Ireland, 2004, p. 22

- ↑ McDonald & Cusack, UDA, p. 30

- ↑ McDonald & Cusack, UDA, p. 32

- 1 2 3 Ciaran De Baroid, Ballymurphy and the Irish War

- ↑ David Boulton, The UVF, 1966–73: An Anatomy of Loyalist Rebellion

- ↑ Alex P. Schmid and Albert J. Jongman, Political Terrorism

- 1 2 Seán Mac Stíofáin Memoirs of a Revolutionary

- ↑ McDonald & Cusack, UDA, pp. 38–39

- ↑ McDonald & Cusack, UDA, p. 39

- ↑ Wood, Crimes of Loyalty, pp. 16–17

- ↑ Wood, Crimes of Loyalty, p. 19

- ↑ McDonald & Cusack, UDA, p. 50

- ↑ Wood, Crimes of Loyalty, pp. 20–21

- ↑ Wood, Crimes of Loyalty, pp. 17–18

- ↑ Wood, Crimes of Loyalty, p. 21

- ↑ Dillon, The Trigger Men, p. 79

- 1 2 Wood, Crimes of Loyalty, p. 23

- ↑ Dillon, The Trigger Men, p. 192

- ↑ Dillon, The Trigger Men, p. 186

- ↑ Dillon, The Trigger Men, pp. 193–94

- ↑ McDonald & Cusack, UDA, pp. 66–67

- ↑ Dillon, The Trigger Men, p. 179

- 1 2 McDonald & Cusack, UDA, p. 49

- ↑ Wood, Crimes of Loyalty, p. 29

- ↑ McDonald & Cusack, UDA, p. 44

- ↑ East Belfast 1973–82, Northern Ireland Elections

- ↑ Taylor, Peter (1999). Loyalists. London: Bloomsbury. p.114.

- ↑ A Chronology of the Conflict – 1973, CAIN Web Service

- ↑ McDonald & Cusack, UDA, p. 68