Tony Jackson | |

|---|---|

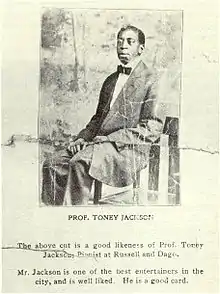

Tony Jackson in the 1910s in Chicago | |

| Born | Antonio Junius Jackson October 25, 1882 New Orleans, Louisiana, U.S. |

| Died | April 20, 1921 (aged 38) |

| Occupation(s) | Musical composer, pianist, singer |

| Years active | 1897–1920 |

Antonio Junius "Tony" Jackson (October 25, 1882 – April 20, 1921)[1] was an American pianist, singer, and composer.

Early life

Jackson was born to a poor African American family in Uptown New Orleans, Louisiana on October 25, 1882. While some sources claim birth dates back to 1876, and a June 5 date, this was likely an error made by his sister Luvina in a later interview, when she appears to have quoted their sister Ida's birth information. Tony did not appear in the 1880 Federal census unlike his older sisters.[2] He was born a twin, along with Prince Albert Jackson, who died in New Orleans on January 5, 1884,[3] at fourteen months of age, further reinforcing the October 1882 birth date as correct. The 1900 Federal census further reinforces the year and month of birth as October 1882,[4] and his 1918 draft record shows a birth date of October 25, although the year reads 1884.[5] His parents were freed slaves.[6] Jackson was epileptic from birth.[6]

Tony showed musical talents at a young age. At about the age of 10 he reportedly constructed a type of crude but working and properly tuned harpsichord out of junk in his back yard, since his family lacked the money to buy or rent a piano.[6] On this contraption young Tony was able to reproduce hymns he heard in church; news of this accomplishment soon spread around the neighborhood and he was offered use of neighbors' pianos and reed organs to practice on. Jackson got his first musical job at age 13,[7] when he began playing piano during off hours at a Tonk run by bandleader Adam Olivier.

Career

Jackson became the most popular and sought after entertainer in Storyville. He was said to be able to remember and play any tune he had heard once, and was hardly ever stumped by obscure requests.[8] His repertory included ragtime, cakewalks (one of his show stopping tricks was to dance a high kicking cakewalk while playing the piano), popular songs of the day from the United States and various nations of Europe and Latin America, blues, and light classics. He was also "openly, almost defiantly homosexual."[7] After hours, he would go with friends to The Frenchman's saloon, which catered to musicians and cross-dressers.[9]

His singing voice was also exceptional, and he was said to be able to sing operatic parts from baritone to soprano range. Fellow musicians and singers were universal in their praise of Jackson, most calling him "the greatest", and even the far-from-modest Jelly Roll Morton ranked Jackson as the only musician better than Morton himself.[7] Morton met Jackson in 1906.[10] Jackson became a mentor to Morton.[7] Jackson also wrote many original tunes, a number of which he sold rights to for a few dollars or were simply stolen from him; some of the old time New Orleans musicians said that some well known Tin Pan Alley pop tunes of the era were actually written by Jackson.

Clarence Williams noted "He was great because he was original in all his improvisations... We all copied him." More than Jackson's music was copied: he was always well dressed.[8] Jackson dressed himself with a pearl gray derby, checkered vest, ascot tie with a diamond stickpin, with sleeve garters on his arms to hold up his cuffs as he played.[11] This became a standard outfit for ragtime and barrelhouse pianists; as one commented "If you can't play like Tony Jackson, at least you can look like him".[12]

Later career and death

Jackson moved to Chicago hoping to have more of an influence on his career.[13] He was also looking for more freedom in his personal life, since being gay was difficult in New Orleans.[14] He lived in an apartment on Wabash Avenue with several members of his family and later they all moved to South State Street.[15]

One of the few tunes published with Jackson's name on it, "Pretty Baby" came out in 1916, although he was remembered performing the song before he left New Orleans and may have written it in 1911.[16] The original lyrics of "Pretty Baby" were said to refer to his male lover of the time.[17] The song inspired the 1978 eponymous film by Louis Malle.[18]

Jackson was resident performer at the De Luxe and Pekin Cafes in Chicago, although in his later years, his voice and dexterity were impaired by disease. Although it has been cited by some as syphilis, the diagnosis at the time of his death was the more likely cirrhosis of the liver which had been progressing for years, in addition to chronic epilepsy.[19] His friends knew that his health was poor and they held a benefit for him on February 17, 1921, calling it the "All Star Tony Jackson Testimonial" and raising $325 for Jackson.[20] He died in Chicago on April 20, 1921.[1]

Jackson's piano rolls can still be heard today and portions of his style are no doubt found in the recordings of younger musicians he influenced, like Jelly Roll Morton, Clarence Williams, and Steve Lewis. In 2011, the Chicago Gay and Lesbian Hall of Fame inducted Jackson into the hall.[21] Jackson was honored for his musical contributions and for living "as an openly gay man when that was rare".[22]

Fictional portrayals

The play Don't You Leave Me Here by Clare Brown, which premiered at West Yorkshire Playhouse in September 2008, deals with his relationship with Jelly Roll Morton.

Jackson appears as a minor character in David Fulmer's Storyville novel Chasing the Devil's Tail.

References

Citations

- 1 2 Carr, Ian, et al. (2004). The Rough Guide to Jazz, p. 396. Rough Guides. ISBN 1-84353-256-5.

- ↑ 1880 Federal census for the family of Antonio Jackson and Rachel (Dennis) Jackson taken in New Orleans, Orleans, Louisiana.

- ↑ New Orleans, Louisiana, city death records 1804-1949, 5 January 1884, as available on Ancestry.com

- ↑ Federal census taken 5 June 1900, New Orleans, Orleans, Louisiana, Ward 12, enumeration district 118, p. 6A

- ↑ "Draft record taken in Chicago, Illinois. An image of this document is available online" (JPG). Doctorjazz.co.uk. Retrieved September 17, 2021.

- 1 2 3 Bullock 2017, p. 21.

- 1 2 3 4 Bullock 2017, p. 22.

- 1 2 Bullock 2017, p. 23.

- ↑ Bullock 2017, p. 24.

- ↑ Brown, Clare (September 25, 2008). "The man of a thousand songs: the forgotten star who inspired Jelly Roll Morton". The Guardian. Retrieved March 31, 2018.

- ↑ Bullock 2017, p. 34.

- ↑ Rose, Al (1978) Storyville, New Orleans: Being an Authentic, Illustrated Account of the Notorious Red Light District, University of Alabama Press. ISBN 0-8173-4403-9

- ↑ Bullock 2017, p. 26.

- ↑ "Tony Jackson · Queer Bronzeville". OutHistory.org. Retrieved March 31, 2018.

- ↑ Bullock 2017, p. 27.

- ↑ Bullock 2017, p. 29.

- ↑ "Gay New Orleans 101". The Advocate: 50. October 11, 2005. Retrieved February 2, 2011.

- ↑ Bullock 2017, p. 33.

- ↑ Chicago, Illinois, death records as available on FamilySearch.com

- ↑ Bullock 2017, p. 32.

- ↑ "Chicago Gay and Lesbian Hall of Fame". Archived from the original on October 17, 2015. Retrieved June 28, 2015.

- ↑ Times, Windy City (September 21, 2011). "2011 Chicago G/L Hall of Fame to induct 11 people, 4 groups - Gay Lesbian Bi Trans News Archive - Windy City Times". Windy City Times.

Sources

Further reading

- New Orleans Jazz: A Family Album by Al Rose and Edmund Souchon

- Biography of Antonio Junius Jackson by Bill Edwards