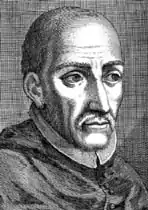

Toribio Rodríguez de Mendoza (1750–1825) was a Peruvian academic.[1] He was a precursor of national independence. He was a priest, a professor, and a tribune.

Early life

He was born on 15 April 1750 in Chachapoyas, while José Antonio Manso de Velasco, count of Superunda, was governing the Viceroyalty of Peru.

When the Republic was born, he was next to his disciples, sharing the responsibilities of the first Peruvian Constituent Congress.

During that time, Chachapoyas was a district of the Bishopric of Trujillo. In this city, the region's main political and intellectual institutions were found. Still a child, he was sent to this city to attend seminary.

He studied Latin and prepared himself to continue ecclesiastic studies of more importance in the Seminar Santo Toribio de Lima (Saint Toribio of Lima Seminar). He entered in this seminar with outstanding notes. He stood out as a brilliant student and in 1770 he obtained the degree of Doctor in Theology in the National University of San Marcos in Lima.

Academic career

His interest in education ran in his family. His parents, Santiago Rodríguez and Josefa Collantes, were wealthy owners of a noble house in the main square of Chachapoyas. They had taken an active part in the efforts to provide the city with a school.

While a student, he began working in the teaching field, showing considerable talent. His prestige as a professor had already grown when the Viceroy Amat named him professor of the Real Convictorio de San Carlos in 1771. This convictorio was created to make up for the shortage that the expulsion of the Jesuits had left in education.

In this center he took the chairs of philosophy and theology.

His talent opened the doors of San Marcos for him, where they delivered him a chair in 1773. During this time he ordained himself in four minor degrees and in 1778 he became a presbyter.

Presbyter

He devoted himself to the affairs of his ministry. Through a contest he won the parish of Marcabal, an indigenous town placed in Huamachuco.

The young priest was already incorporated into the intellectual elite of the epoch. He was called to Lima. He was entrusted with the vice-chancellor of the Convictorio Carolino and one year later, in 1786, the viceroy Teodoro de Croix made him chancellor of this center of studies.

Until then, Rodríguez had been an eager and passionate reader of the philosophers whose thought guided Europe. He rebuilt the college buildings, today University of San Marcos, and put into practice new education plans. De Mendoza was one of the first people who saw the transformation towards an independent Peru.

Tribune

He fought to impose education in a common language, the study of natural sciences, and to introduce professions. He supported the idea that it was necessary to offer a profession to young people other than law or the clergy.

Despite his consecration to form a leading class, he also worried about popular education, trusting that the language unit would be the way to achieve racial equality.

In 1814, his disciples and friends founded the Sociedad Filantrópica (Philanthropic Society) to spread the ideals of the American Revolution with clear anti-monarchist tendency.

The professor was already aged. Opponents of his reforms accused him of propagating prohibited ideas.

His conduct was investigated in a more or less covered up way. The economic situation of the college was precarious and in such circumstances, he resigned to as academic chancellor in 1815. However Abascal did not accept his resignation. His resignation was accepted only in 1817 by Viceroy Pezuela.

At the arrival of the Expedición Libertadora of San Martin, his illnesses did not prevent him from leaving his retirement and join the orders of the liberating government. In this way he had the opportunity to take part in the birth of the Peruvian Republic as a member of the first Peruvian Constituent Congress.

Legacy

Toribio Rodríguez de Mendoza National University was named after him.[2]

References

- ↑ Rodríguez de Mendoza, Toribio; Rivero y Aranibar, Mariano de (1951). Lugares teológicos. Princeton Theological Seminary Library. Lima.

- ↑ Castillo, Miriam Victoria Bacalla Del; Chamiquit, Clelia Jima; Revilla, Adolfo Cacho; Vega, Yajaira Lizeth Carrasco (26 November 2021). "Applicable technologies to improve teaching processes at the higher education level". Revista Iberoamericana de Educación. 4 (3). doi:10.31876/ie.v4i3.68. ISSN 2737-632X. S2CID 246173443.