The F4 Fayetteville, Tennessee, tornado dissipating after damaging the town. | |

| Type | Tornado outbreak |

|---|---|

| Duration | February 29, 1952 |

| Highest gust | 63 miles per hour (101 km/h) |

| Tornadoes confirmed | 8 |

| Max. rating1 | F4 tornado |

| Duration of tornado outbreak2 | 4 hours, 15 minutes |

| Largest hail | .75 inches (1.9 cm) |

| Maximum snowfall or ice accretion | 10 inches (25 cm) |

| Fatalities | 5 fatalities (+4 non-tornadic), 336 injuries (+14 non-tornadic) |

| Damage | $3.100 million (1952 USD)[1] $34.2 million (2024 USD) |

| Areas affected | Tennessee, Alabama, Georgia |

Part of the tornado outbreaks of 1952 1Most severe tornado damage; see Fujita scale 2Time from first tornado to last tornado | |

A localized, but destructive and deadly tornado outbreak impacted Tennessee, Alabama, and Georgia on Leap Day in 1952. Thanks in part to unseasonably strong jet stream winds and a strong cold front, eight tornadoes left trails of damage and casualties. The tornado to cause the most casualties was an F1 tornado in Belfast, Tennessee, which killed three people and injured 166. A violent F4 tornado moved through Fayetteville, Tennessee, destroying most of the town and killing two and injuring 150 others. On the north side of Fort Payne, Alabama, an F3 tornado caused major damage and injured 12 people. In all, the outbreak killed five, injured 336, and caused $3.1 million (1952 USD) in damage. Four more fatalities and 14 more injuries occurred from other non-tornadic events as well.

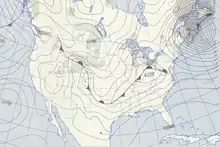

Meteorological synopsis

On February 29, 1952, a strong cold front extending down from a low-pressure area spanned from Southern Indiana and Central Ohio southwestward through Central Arkansas into North Texas. A strong upper-level jet stream at the 200 mbar level was observed moving northeast out of Texas into the Tennessee Valley region with winds ranging from 110 to 130 miles per hour (180 to 210 km/h) or more. A strong upper-level trough at the 500 mbar level was also noted. The trough extended southeastward through the Central and Southern Plains states, where a second and third surface low had just combined behind the surface cold front. The combination of the strong cold front, strong low, and the unusually strong jet stream winds, led to the development of severe thunderstorms and tornadoes across portions of the Tennessee Valley in southern Middle Tennessee and Northeast Alabama.[2][3]

Confirmed tornadoes

| FU | F0 | F1 | F2 | F3 | F4 | F5 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 8 |

February 29 event

| F# | Location | County / Parish | State | Start coord. |

Time (UTC) | Path length | Max. width | Summary |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F1 | Belfast | Marshall | TN | 35°25′N 86°42′W / 35.42°N 86.70°W | 22:00–? | 0.1 miles (0.16 km) | 100 yards (91 m) | 3 deaths – A brief, but catastrophic tornado destroyed a number of buildings in the center of Belfast as it struck four farms. Two of these farms were destroyed. 166 people were injured and losses totaled $25,000. As of 2024, this is the most injuries ever caused by an F1/EF1 tornado in the United States, although sources vary tremendously on the actual casualty toll as it appears that the injury count was actually for the F4 tornado listed below. Tornado researcher Thomas P. Grazulis assessed the tornado as having caused F3-level damage while only killing one person.[2][5][6][7] |

| F4 | Downtown Fayetteville | Lincoln | TN | 35°09′N 86°35′W / 35.15°N 86.58°W | 22:30–? | 2 miles (3.2 km) | 300 yards (270 m) | 2 deaths – See section on this tornado – 150 people were injured and damage was estimated at $2.5 million. Grazulis assessed the tornado as having caused F3-level damage.[2][5][3][8] |

| F2 | Viola | Warren | TN | 35°32′N 85°51′W / 35.53°N 85.85°W | 22:40–? | 1 mile (1.6 km) | 400 yards (370 m) | The storm that had "practically spent itself over Fayetteville" produced this strong, large tornado about 50 miles (80 km) to the northeast, damaging or destroying several farm buildings. Damage was estimated at $25,000.[2][5][9] |

| F3 | Northern Fort Payne | DeKalb | AL | 34°30′N 85°42′W / 34.5°N 85.7°W | 23:00–? | 3.3 miles (5.3 km) | 400 yards (370 m) | See section on this tornado – There were 12 injuries.[2][5][3][10][11] |

| F2 | W of Claxton to Englewood | McMinn | TN | 35°18′N 84°40′W / 35.3°N 84.67°W | 23:30–00:30 | 15.3 miles (24.6 km) | 587 yards (537 m) | A large tornado embedded in a mile-wide swath of hail moved eastward through the Eastanollee Valley before dissipating near the Etowah Highway. Many homes, barns, stores, and a church were destroyed or damaged. Many cattle and horses were killed as well. Damage to crops was confined to hay stored in thee barns that were destroyed. Losses totaled $250,000.[2][5][12] |

| F2 | WNW of Vandiver to E of Parhams | Franklin | GA | 34°24′N 83°20′W / 34.4°N 83.33°W | 01:00–? | 7.8 miles (12.6 km) | 77 yards (70 m) | A destructive tornado north of Carnesville moved eastward from the Strange district. Three or more homes and numerous smaller buildings were destroyed with moderate to heavy damages to several other homes and many smaller buildings. Many trees and utility lines were blown down and a substantial number of poultry was lost. Losses totaled $25,000.[2][5][13] |

| F2 | NW of Homer to Mt. Pleasant to W of Jewelville | Banks | GA | 34°22′N 83°35′W / 34.37°N 83.58°W | 01:30–? | 9.4 miles (15.1 km) | 300 yards (270 m) | A destructive tornado moved eastward, from Hickory Flat to Nails Creek, passing north of Homer and striking Mt. Pleasant. A total of 10 or more homes, a school, and numerous chicken houses and barns were destroyed with moderate to heavy damages to 25 or more homes, and many smaller buildings. Many trees and utility lines were blown down, and a large number of poultry lost. Three people were injured, and damage was estimated at $250,000.[2][5][14] |

| F2 | S of Pendergrass | Jackson | GA | 34°07′N 83°40′W / 34.12°N 83.67°W | 02:15–? | 0.2 miles (0.32 km) | 17 yards (16 m) | Although information for this event is incomplete, a strong tornadic event is believed to have taken place. One dwelling was destroyed, injuring five occupants, while two other dwellings, a tenant house, and two barns, were unroofed. A large chicken house was also destroyed, causing the loss of more than 8,000 chicks. Losses totaled $25,000.[2][5][15] |

Fayetteville, Tennessee

| F4 tornado | |

|---|---|

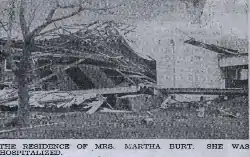

F4 damage in Fayetteville | |

| Highest winds |

|

| Max. rating1 | F4 tornado |

| Fatalities | 2 fatalities, 150 injuries |

| Damage | $2.5 million (1952 USD) |

| Areas affected | Middle Tennessee |

| 1Most severe tornado damage; see Fujita scale | |

This large, violent, and deadly F4 tornado touched down on the west side of downtown Fayetteville just northwest of the Old Lincoln County Hospital and moved east-northeast directly through it before dissipating near the Lincoln County Livestock Market along US 64. It traveled 2 miles (3.2 km)[nb 3] and was 300 yards (270 m) wide.

Of the 1,828 buildings in Fayetteville, 932 were damaged or destroyed. In all, 139 homes were destroyed, 152 had major damage, and another 164 sustained minor damage. An additional 23 farm buildings were destroyed, 15 others had major damage, and 11 more had minor damage. 105 businesses were destroyed, while 58 others had major damage; 37 more sustained minor damage, and nine additional ones had superficial damage. Damage to six churches alone in downtown Fayetteville were estimated at $300,000. Several business houses were destroyed, power and communications lines were damaged over a large area; and hundreds of huge shade trees were uprooted. Two people were killed, 150 others were injured, and losses totaled $2.5 million, although the NWS Huntsville and Climatological Data National Summary (CDNS) gives a value of over $3 million. As of 2022, this is one of only two violent tornadoes to strike on a Leap Day (February 29) with the other being another EF4 tornado that struck Harrisburg, Illinois, in 2012. Despite the extreme damage, Grazulis assessed the tornado as having caused F3-level damage.[2][5][3][8]

Fort Payne, Alabama

| F3 tornado | |

|---|---|

Tornado damage in Fort Payne, Alabama. Photo Courtesy of Maitland E. Davidson, Fort Payne Journal via Carlton and Lana Floyd, De Kalb County, Alabama, Geneaological Society | |

| Highest winds |

|

| Max. rating1 | F3 tornado |

| Fatalities | 12 injuries |

| Damage | Unknown |

| Areas affected | Northern Alabama |

| 1Most severe tornado damage; see Fujita scale | |

This large, intense F3 tornado first touched down between 15th and 16th Streets in Minvale on the north side of Fort Payne. It blew down three large trees upon touching down, including one that missed a house by only 15 feet (4.6 m). It then leveled a house, "leaving only enough...for a good sized bonfire." All but one of the five occupants escaped without injury. As the tornado moved in the direction of Gault Avenue (US 11), a large storage house was leveled "as flat as a pool table." An electric refrigerator, a bicycle, other toys and large pieces of furniture were all crushed inside the structure. The tornado then lifted for about 20 feet (6.1 m) before touching down again and unroofing a house, which was twisted about 10 inches (25 cm) off of its foundation. The tornado then tore down large trees, tore off roofs, smashed out windows, and then tore into the telephone and power lines along Gault Avenue at the Black Motel, where considerable damage was done to the owner's home.

As the tornado tore through Wills Valley, large sheets of tin were hurled into power and telephone lines, severing dozens of the wires. A huge neon sign at the Lefty Cooper café, which was on the southern fringe of the tornado, was turned 90° from north–south to east–west, and a large cattle truck at the Fort Payne Sales Barn was completely flipped over. Additionally, two nearby cars were tossed 100 yards (91 m) before being rolled up into a ball of scrap. Behind the Sales Barn, sheets of galvanized roofing metal were strewn through a field up to a mile away, and many sheets lodged themselves in trees all over Lookout Mountain. The tornado also heavily damaged another house on the mountain that overlooked Beason Gap before weakening and dissipating in Lakewood shortly after that.

The tornado traveled 3.3 miles (5.3 km), was 400 yards (370 m) wide [nb 4], destroyed 12 homes, and damaged 20 other homes. It also destroyed 25 other buildings and damaged 35 others. Although no damage value was given, it is estimated that tornado did anywhere between $150,000 to $400,000 in damage. There were 12 injuries.[2][5][3][10][11]

Non-tornadic impacts

Early on February 29, in Valley View, Texas, strong straight-line winds accompanied by pea-sized hail damaged the roofs of multiple buildings. That evening, a destructive squall line passed over Chattanooga, Tennessee, toppling sign boards, radio and TV aerials, breaking plate glass windows along Market and Broad Streets, and breaking telephone and power lines. The squall line moved rapidly eastward, passing over Lovell Field at 8:17 pm and capsizing several small aircraft. Winds were measured at around 60 miles per hour (97 km/h) with a peak of 63 miles per hour (101 km/h). Another windstorm moved through Cleveland, Tennessee, although damage from this storm was confined to blown-down sign boards and forest land. Hailstones approximately 3⁄4 inch (1.9 cm) in diameter accompanied the storm. A 1⁄2 mi (0.80 km) area in Monteagle, Tennessee, suffered heavy damage, with multiple buildings unroofed and signs blown down. Light damage also occurred outside this small area.[2]

The same storm system bought heavy snow to parts of the Mid-Atlantic and Northeastern United States on March 1. Snowfall rates of 1 inch (2.5 cm) an hour slowed traffic to a crawl in multiple counties of Southeastern Pennsylvania. In Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, a man died while shoveling heavy snow. In Philadelphia, one person was killed and four others were injured after their car, whose driver was blinded by snow, crashed into a traffic island. In New Jersey, 3 to 10 inches (7.6 to 25.4 cm) of snow was recorded throughout the state, with the heaviest snow in the south. One person was killed and 10 others were injured due to afternoon rush hour traffic accidents attributed to the storm. Most roads were blocked during the morning hours, but normal traffic resumed by mid- to late afternoon. Damage was estimated at several thousand dollars. Most of the damage was to automobiles, although there was some damage to power and communication lines. In Delaware, an Air Force corporal was killed when he was hit by a car while pushing his own car, which had stalled in the snow. Traffic tie-ups were also reported Maryland and a few power failures were reported for several hours in Baltimore.[2]

Severe weather from February 29 continued overnight into the morning of March 1. In Darlington, South Carolina, trees were uprooted and limbs and television aerials were blown down. Another thunderstorm in Newberry, South Carolina, destroyed a home and damaged a few others, although the event may have occurred late on February 29.[2]

Aftermath and historical significance

The F4 tornado that hit Fayetteville, Tennessee, was the fourth tornado to strike the city in just over 100 years. The previous tornadoes occurred on March 14, 1851; March 27, 1890; and April 29, 1909, all of which took similar paths. An EF2 tornado would also follow a path similar to this tornado on March 24, 2023.[16] In Fort Payne, Alabama, the northern half of town was left without lights and telephones for several hours as power crews worked under large spot lights to remove hot wires and restore new ones as best they could.[3]

See also

Notes

- ↑ All dates are based on the local time zone where the tornado touched down; however, all times are in Coordinated Universal Time and dates are split at midnight CST/CDT for consistency.

- ↑ Prior to 1994, only the average widths of tornado paths were officially listed.[4]

- ↑ NWS Huntsville says the tornado travelled 7 miles (11 km)

- ↑ NWS Huntsville says 1,200 yards (1,100 m) wide

References

- ↑ "Tornado Summaries". National Weather Service. National Center for Environmental Information. Retrieved 28 August 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 "Climatological Data: National summary". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Environmental Data and Information Service, National Climatic Center. 1952. Retrieved 19 April 2022.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 US Department of Commerce, NOAA. "February 29th, 1952 Fayetteville Tornado Weather Setup". National Weather Service. Retrieved 30 August 2020.

- ↑ Brooks 2004, p. 310.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Grazulis, T. P. (1990). Significant Tornadoes: A chronology of events. Tornado Project. ISBN 9781879362024. Retrieved 19 April 2022.

- ↑ Tennessee Event Report: F1 Tornado. National Weather Service (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. Retrieved 30 August 2020.

- ↑ "F1 Tornado". Facts Just for Kids. 19 July 2021. Retrieved 5 January 2022.

- 1 2 Tennessee Event Report: F4 Tornado. National Weather Service (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. Retrieved 30 August 2020.

- ↑ Tennessee Event Report: F2 Tornado. National Weather Service (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. Retrieved 30 August 2020.

- 1 2 US Department of Commerce, NOAA. "Alabama Tornadoes 1952". www.weather.gov. Retrieved 24 December 2021.

- 1 2 Alabama Event Report: F3 Tornado. National Weather Service (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. Retrieved 31 August 2020.

- ↑ Tennessee Event Report: F2 Tornado. National Weather Service (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. Retrieved 1 September 2020.

- ↑ Georgia Event Report: F2 Tornado. National Weather Service (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. Retrieved 1 September 2020.

- ↑ Georgia Event Report: F2 Tornado. National Weather Service (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. Retrieved 1 September 2020.

- ↑ Georgia Event Report: F2 Tornado. National Weather Service (Report). National Centers for Environmental Information. Retrieved 1 September 2020.

- ↑ National Weather Service in Huntsville, Alabama (March 25, 2023). NWS Damage Survey for 03/24/23 Tornado Event (Report). Iowa Environmental Mesonet. Retrieved March 25, 2023.

Works cited

- Brooks, Harold E. (April 2004). "On the Relationship of Tornado Path Length and Width to Intensity". Weather and Forecasting. Boston: American Meteorological Society. 19 (2): 310. Bibcode:2004WtFor..19..310B. doi:10.1175/1520-0434(2004)019<0310:OTROTP>2.0.CO;2. Retrieved 11 September 2019.