| Trans-African Highway network | |

|---|---|

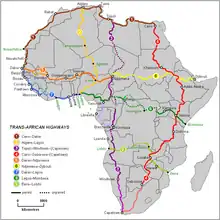

Map of International TAH-road network | |

| System information | |

| Formed | 2007 |

| Highway names | |

| TAH 1 | Cairo-Dakar Highway |

| TAH 2 | Algiers–Lagos Highway |

| TAH 3 | Tripoli–Cape Town Highway |

| TAH 4 | Cairo-Cape Town Highway |

| TAH 5 | Dakar-Ndjamena Highway |

| TAH 6 | Ndjamena-Djibouti Highway |

| TAH 7 | Dakar-Lagos Highway |

| TAH 8 | Lagos-Mombasa Highway |

| TAH 9 | Beira-Lobito Highway |

The Trans-African Highway network comprises transcontinental road projects in Africa being developed by the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa (UNECA), the African Development Bank (ADB), and the African Union in conjunction with regional international communities. They aim to promote trade and alleviate poverty in Africa through highway infrastructure development and the management of road-based trade corridors. The total length of the nine highways in the network is 56,683 km (35,221 mi).

In some documents the highways are referred to as "Trans-African Corridors" or "Road Corridors" rather than highways. The name Trans-African Highway and its variants are not in wide common usage outside of planning and development circles, and as of 2014 one does not see them signposted as such or labelled on maps, except in Kenya and Uganda where the Mombasa–Nairobi–Kampala–Fort Portal section (or the Kampala–Kigali feeder road) of Trans-African Highway 8 is sometimes referred to as the "Trans-Africa Highway".

Background

Need for the highway system

Colonial powers and, later, competing superpowers and regional powers, generally did not encourage road links between their respective spheres except where absolutely necessary (i.e. trade), and in newly independent African states, border restrictions were often tightened rather than relaxed as a way of protecting internal trade, as a weapon in border disputes, and to increase the opportunities for official corruption.

Poverty affects development of international highways when scarce financial resources have to be directed towards internal rather than external priorities.

The agencies developing the highway network are influenced by the idea that road infrastructure stimulates trade and so alleviates poverty, as well as benefiting health and education since they allow medical and educational services to be distributed to previously inaccessible areas.

On 1 July 1971 Robert K. A. Gardiner, the Executive Secretary of the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa (UNECA), established the Trans-African Highway Bureau to oversee the development of a continental road network.[1]

Wars and conflicts

As well as preventing progress in road construction, wars and conflicts have led to the destruction of roads and river crossings, have prevented maintenance and have often closed vital links. Sierra Leone, Liberia, the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Angola are all in rebuilding phases after war. Wars in the Democratic Republic of the Congo set back road infrastructure in that country by decades and cut the principal route between East and West Africa. In recent years, security considerations have restricted road travel in the southern parts of Morocco, Algeria, Libya and Egypt as well as in northern Chad and much of Sudan.

Trans-African highways can only develop in times of peace and stability, and in 2007 the future looks brighter, with the southern Sudan conflict being the only one currently affecting development of the network (highway 6). Lawlessness rather than war hampers progress in developing highway 3 between Libya and Chad, and though economic instability could affect maintenance of paved highways 4 and 9 though Zimbabwe, there are practical alternatives through neighbouring countries. Conflicts in Somalia do not affect the network as that is the largest African country with no trans-African highways, but they will affect the development of feeder roads to the network.

Principles and processes

Using existing national highways as much as possible, the aim of the development agencies is to identify priorities in relation to trade, to plan the highways, and to seek financing for the construction of missing links and bridges, the paving of sections of earth and gravel roads, and the rehabilitation of deteriorated paved sections.

The need to reduce delays caused by highway checkpoints and border controls or to ease travel restrictions has also been identified, but so far solutions have not been forthcoming. Rather than just having international highways over which each country maintains its regulations and practices, there is a need for transnational highways over which regulations and practices are simplified, unified and implemented without causing delays to goods and travellers.

Features of the network

Countries served

The network as planned reaches all the continental African nations except Burundi, Eritrea, Eswatini, Somalia, Equatorial Guinea (Rio Muni), Lesotho, Malawi, Rwanda and South Sudan. Of these, Rwanda, Malawi, Lesotho and Eswatini have paved highways connecting to the network, and the network reaches almost to the border of the others.

Missing links

More than half of the network has been paved, though maintenance remains a problem. There are numerous missing links in the network where tracks are impassable after rain or hazardous due to rocks, sand, and sandstorms. In a few cases, there has never been a road of any sort, such as the 200 km gap between Salo in the Central African Republic and Ouésso in the Republic of the Congo on highway 3. The missing links arise mainly because the section does not have a high national priority as opposed to a regional or transcontinental priority.

As a result of missing links, of the five major regions—North, West, Central, East, and Southern Africa—road travel in all weather is only relatively easy between East and Southern Africa, and that relies on a single paved road through southwestern Tanzania (the Tanzam Highway).

While North Africa and West Africa are linked across the Sahara, the main deficiency of the network is that there are no paved highways across Central Africa. Not only does this prevent road trade between East and West Africa, or between West and Southern Africa, but it restricts trade within Central Africa. Although there may be paved links from West, East, or Southern Africa to the fringes of Central Africa, those links do not penetrate very far into the region. The terrain, rainforest, and climate of Central Africa, particularly in the catchments of the lower and middle Congo River and the Ubangui, Sangha, and Sanaga Rivers, present formidable obstacles to highway engineers, and paved roads there have short lifespans. Further north in Cameroon and Chad, hilly terrain or plains prone to flooding have restricted the development of local paved road networks.

Through this forbidding environment, three Trans-African Highways are planned to cross in the east–west direction (highways 6, 8, and 9) while one will cross north to south (highway 3). As of 2014, all have substantial missing links in Central Africa.

Description of the highways in the network

Nine highways have been designated, in a rough grid of six mainly east–west routes and three mainly north–south routes. A fourth north–south route is formed from the extremities of two east–west routes.

East-west routes

Starting with the most northerly, the east–west routes are:

- Trans-African Highway 1 (TAH 1), Cairo–Dakar Highway, 8,636 km (5,366 mi): a mainly coastal route along the Mediterranean coast of North Africa, continuing down the Atlantic coast of North-West Africa; substantially complete, although the border between Algeria and Morocco is closed. TAH 1 joins with TAH 7 to form an additional north–south route around the western extremity of the continent. Connects with M40 of the Arab Mashreq International Road Network.

- Trans-African Highway 5 (TAH 5), Dakar–N'Djamena Highway, 4,496 km (2,794 mi) , also known as the Trans-Sahelian Highway, linking West African countries of the Sahel, about 80% complete.

- Trans-African Highway 6 (TAH 6), N'Djamena–Djibouti Highway, 4,219 km (2,622 mi): contiguous with TAH 5, continuing through the eastern Sahelian region to Indian Ocean port of Djibouti. The approximate route of TAH 5 and TAH 6 was originally proposed in the early 20th century as an aim of the French Empire.

- Trans-African Highway 7 (TAH 7), Dakar–Lagos Highway, 4,010 km (2,490 mi): also known as the Trans–West African Coastal Road, about 80% complete. This highway joins with TAH 1 to form an additional north–south route around the western extremity of the continent.

- Trans-African Highway 8 (TAH 8), Lagos–Mombasa Highway, 6,259 km (3,889 mi): which is contiguous with TAH7 and forms with it a 10,269-km east–west crossing of the continent. The Lagos–Mombasa Highway's eastern half is complete through Kenya and Uganda, where locally it is known as the Trans-Africa Highway (the only place where the name is in common use). Its western extremity in Nigeria, Cameroon and Central African Republic is mostly complete but a long missing link across DR Congo currently prevents any practical use through the middle section.

- Trans-African Highway 9 (TAH 9), Beira–Lobito Highway, 3,523 km (2,189 mi): substantially complete in the eastern half but the western half through Angola and south-central DR Congo requires reconstruction.

North-south routes

Starting with the most westerly, these are:

- Trans-African Highway 2 (TAH 2), Algiers–Lagos Highway, 4,504 km (2,799 mi): also known as the Trans-Sahara Highway: substantially complete, only 200 km (120 mi) of desert track remains to be paved, but border and security controls restrict usage.

- Trans-African Highway 3 (TAH 3), Tripoli–Windhoek–(Cape Town) Highway, 10,808 km (6,716 mi): this route has the most missing links and requires the most new construction, as only national paved roads in Libya, Cameroon, Angola, Namibia and South Africa can be used to any extent. South Africa was not originally included, as the highway was first planned in the Apartheid era, but it is now recognized that it would continue to Cape Town.

- Trans-African Highway 4 (TAH 4), Cairo–Gaborone–(Pretoria/Cape Town) Highway, 10,228 km (6,355 mi): the completion of the stretch of highway from Dongola to Abu Simbel Junction in Northern Sudan and the road from the Galabat border crossing in North-Western Ethiopia leaves no section unpaved; the road section between Babati and Dodoma in central Tanzania was completed in May 2018.[2] The section between Isiolo and Moyale in northern Kenya (dubbed 'the road to hell' by overland travellers) has recently been completed creating a smooth crossing across Kenya. Crossing the Egypt-Sudan border by road has been prohibited for a number of years, a vehicle ferry on Lake Nasser is used instead. As with TAH 3, South Africa was not originally included as the idea was first proposed in the Apartheid era, but it is now recognized that it would continue to Pretoria and Cape Town. Except for passing through Ethiopia, the route roughly coincides with proposals for the Cape to Cairo Road put forward in the early 20th century British Empire.

As noted above, TAH 1 and TAH 7 join to form an additional north–south route around the western extremity of the continent between Monrovia and Rabat.

Regional highway projects in Africa

Regional international communities are heavily involved in trans-African highway development and work in conjunction with the ADB and UNECA. For example:

- The Arab Maghreb Union drives the development and maintenance of the Tripoli to Nouakchott section of TAH 1.

- The Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) drives the development of and maintenance of TAH 5 and 7.

- the Southern African Development Community (SADC) has an extensive network of road projects and trade corridors in southern Africa. TAH 9 and the southern ends of TAH 3 and 4 utilize regional highways developed by SADC or its forerunners. In particular SADC manages road and rail corridors from landlocked areas to ports.

See also

- Other intercontinental highway systems: SADC Regional Trunk Road Network, Asian Highway Network, International E-road network and Arab Mashreq International Road Network

- Trans-African Railway

- African transcontinental railroad

- Environmental impact of roads

References

- ↑ Arnold & Weiß 1977, p. 152.

- ↑ Cairo to Cape Town road: Linking Tanzania to the rest of Africa, African Review of Business and Technology, published 1 May 2018, accessed 11 May 2021

- African Development Bank/United Nations Economic Commission For Africa: "Review of the Implementation Status of the Trans African Highways and the Missing Links: Volume 2: Description of Corridors". 14 August 2003. Retrieved 14 July 2007.

- Arnold, Guy; Weiß, Ruth (1977). Strategic Highways of Africa. London: Julian Friedman. ISBN 9780904014129. OCLC 1037140194.

Further reading

- Selima Sultana; Joe Weber, eds. (2016). "Trans-African Highway". Minicars, Maglevs, and Mopeds: Modern Modes of Transportation Around the World. ABC-CLIO. pp. 304+. ISBN 978-1-4408-3495-0.