| Transfusion associated circulatory overload | |

|---|---|

| Other names | TACO[1] |

| |

| Peripheral edema in the lower extremity that can result from volume overload following large volume blood transfusions. | |

| Specialty | Hematology |

| Symptoms | dyspnea, orthopnea, peripheral edema, hypertension. |

| Usual onset | Within 12 hours of transfusion |

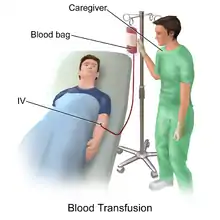

In transfusion medicine, transfusion-associated circulatory overload (aka TACO) is a transfusion reaction (an adverse effect of blood transfusion) resulting in signs or symptoms of excess fluid in the circulatory system (hypervolemia) within 12 hours after transfusion.[2] The symptoms of TACO can include shortness of breath (dyspnea), low blood oxygen levels (hypoxemia), leg swelling (peripheral edema), high blood pressure (hypertension), and a high heart rate (tachycardia).[3]

It can occur due to a rapid transfusion of a large volume of blood but can also occur during a single red blood cell transfusion (about 15% of cases).[2] It is often confused with transfusion-related acute lung injury (TRALI), another transfusion reaction. The difference between TACO and TRALI is that TRALI only results in symptoms of respiratory distress while TACO can present with either signs of respiratory distress, peripheral leg swelling, or both.[4] Risk factors for TACO are diseases that increase the amount of fluid a person has, including liver, heart, or kidney failure, as well as conditions that require many transfusions. High and low extremes of age are a risk factor as well.[5][6][7]

The management of TACO includes immediate discontinuation of the transfusion, supplemental oxygen if needed, and medication to remove excess fluid.[8]

Symptoms and signs

The primary symptoms of TACO are signs of respiratory distress (shortness of breath, low oxygen levels in the blood) along with signs of excess fluid within the circulatory system (leg swelling, high blood pressure, and an elevated heart rate).[3]

On physical exam, patients may present with crackles when listening to the lungs, a murmur (S-3 murmur) when listening to the heart, leg swelling, and distended veins in the neck (jugular venous distension).[3]

Risk factors

Risk factors that can promote the development of TACO include conditions that predispose individuals to excess fluid in the circulatory system (liver failure causing low levels of protein in the blood (hypoalbuminemia),[5] heart failure,[6][7] renal insufficiency,[6][7] or nephrotic syndrome[7]), conditions that place increased stress on the respiratory system (lung disease[6]), and conditions necessitating large volume transfusions (severe anemia[6]). Age has also been found to be a risk factor where individuals less than 3 years old and over 60 years old are at increased risk.[5]

In addition, the risk of TACO increases as the number of units of blood products transfused increases.[9] Table 1 shows the volume transfused with each blood product. Multiple blood products and blood products with larger volumes increase the risk for TACO.[7]

| Blood Product[10] | Volume (mL)[10] |

|---|---|

| Whole blood | 520 mL |

| Red Blood Cells | 340 mL |

| Concentrated platelets | 50 mL |

| Platelets | 300 mL |

| Cryoprecipitate | 15 mL |

| Fresh frozen plasma | 225 mL |

Diagnosis

The National Healthcare Safety Safety Network division of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) released an updated criteria table in 2021:[11]

Patients diagnosed with TACO should have at least 1 of the following two characteristics within 12 hours after the transfusion was ended:

- Acute or worsening respiratory distress (tachypnea, dyspnea, cyanosis, and/or hypoxemia) in the absence of other causes

- Evidence of acute or worsening pulmonary edema (by physical examination or chest imaging)

Along with:

- Elevations in brain-natriuretic peptide (BNP) or N-terminal (NT)-pro BNP.

- Evidence of cardiovascular system changes (tachycardia, hypertension, widened pulse pressure, jugular venous distension, peripheral edema)

- Evidence of fluid overload.

Classification

TACO can be categorized by severity:[11]

- Non-severe - where no permanent damage would arise if treatment was not given. However, treatment is still needed.

- Severe - where the patient either requires hospitalization as a result or, if already hospitalized, has an extended length of stay as a result. Treatment is needed to avoid permanent damage.

- Life-threatening - where intensive care such as vasopressor agents and mechanical ventilation is required in order to prevent death.

- Death

Differential diagnosis

TACO and transfusion-related acute lung injury (TRALI) are both complications following a transfusion, and both can result in respiratory distress.[2] TACO and TRALI are often difficult to distinguish in the acute situation.

Assessing fluid status is key in differentiating between the two. In TACO, the patient will always have a positive fluid balance and will often present with hypertension, jugular venous distension, elevated BNP, peripheral edema, and will respond well to diuretics. In contrast, TRALI is not associated with fluid overload and the patient may have a positive, even, or net fluid balance. Patients with TRALI often present with hypotension, no signs of right-heart fluid overload, normal BNP, and lack of clinical improvement in response to diuretics.[12][13][6]

Other causes of edema that can promote a volume-overloaded state and predispose individuals to TACO include: heart failure, renal insufficiency, nephrotic syndrome, cirrhosis, and chronic venous insufficiency.[14]

Pathogenesis

The development of TACO is thought to be due to a 2-hit mechanism.[15] The first hit is the state of the patient and the second hit is the blood transfusion itself. A patient may be receiving blood due to any number of causes and may have heart or kidney dysfunction which can lead to excess fluid. Upon transfusion of the blood product, the patient is overwhelmed by the excess fluid and develops symptoms related to volume overload.

The clinical symptoms from TACO are due to an excess of fluid within the circulatory system. As a result, there is increased pressure within the circulatory system, resulting in fluid moving into the surrounding tissues.[4] In the lungs, the extra fluid accumulates into the air sacs within the lung, causing difficulties in oxygen getting into the blood. This results in low blood oxygen levels and shortness of breath. In the arms and legs, the fluid accumulates in the tissues, causing swelling. This is most prominent in the legs due to the effects of gravity. Conditions that predispose to increased hydrostatic pressure (heart failure and renal insufficiency) or decreased oncotic pressure (liver failure, malnutrition, nephrotic syndrome) places individuals at increased risk for TACO.

Prevention

Transfusion associated circulatory overload is prevented by avoiding unnecessary transfusions by following strict criteria necessitating blood transfusion, closely monitoring patients receiving transfusions, and transfusing smaller volumes of blood at a slower rate. Blood products are typically transfused at 2.0 to 2.5 ml/kg per hour but can be reduced to 1.0 ml/kg per hour for individuals at increased risk for TACO.[16] Patients susceptible to volume overload (e.g., renal insufficiency or heart failure) may be pre-treated with a diuretic either during or immediately following transfusion to reduce the overall net fluid balance.[8]

Management

If TACO is suspected, the transfusion is stopped immediately and the patient is sat upright to prevent the fluid from backing up into the lungs. Treatment is two-fold: respiratory support and removal of excess fluid.[8] Patients with respiratory distress and/or hypoxemia are given supplemental oxygen or ventilatory support (through non-invasive or mechanical ventilation, if needed). To remove the excess fluid, patients are given diuretic therapy and their urine output is closely monitored to quantitate the amount removed.

Epidemiology

The reported incidence of TACO is difficult to determine as many cases may be undetected but its incidence is estimated at 1% of all individuals receiving transfusion, with hospitalized patients being at increased risk.[17][18] TACO is the most commonly reported cause of transfusion-related death and major morbidity in the UK,[2] and second most common cause in the USA.[19]

History

Death from pulmonary edema as the result of circulatory overload following transfusion was reported as early as 1936.[20] However, the term 'transfusion associated circulatory overload' was not coined until the 1990s when it was seen as a separate complication following blood transfusion.[21]

References

- ↑ Agnihotri, Naveen; Agnihotri, Ajju (2014). "Transfusion associated circulatory overload". Indian Journal of Critical Care Medicine. 18 (6): 396–398. doi:10.4103/0972-5229.133938. PMC 4071685. PMID 24987240.

- 1 2 3 4 Bolton-Maggs, Paula (Ed); Poles, D; et al, on behalf of the Serious Hazards of Transfusion (SHOT) Steering Group (2017). The 2016 Annual SHOT Report (2017) (PDF). Serious Hazards of Transfusion (SHOT). ISBN 978-0-9558648-9-6.

- 1 2 3 "Transfusion-Associated Circulatory Overload (TACO)". 15 July 2004. Archived from the original on June 20, 2008.

- 1 2 Malek, Ryan; Soufi, Shadi (2021), "Pulmonary Edema", StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, PMID 32491543, retrieved 2021-11-11

- 1 2 3 Bolton-Maggs, PHB; Poles, D, eds. (2018). "The 2017 Annual SHOT Report (2018)" (PDF).

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Transfusion-associated circulatory overload (TACO)(2018)" (PDF). ISBT. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 October 2021. Retrieved 24 June 2019.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Clifford, Leanne; Jia, Qing; Subramanian, Arun; Yadav, Hemang; Schroeder, Darrell R.; Kor, Daryl J. (March 2017). "Risk Factors and Clinical Outcomes Associated with Perioperative Transfusion-associated Circulatory Overload". Anesthesiology. 126 (3): 409–418. doi:10.1097/ALN.0000000000001506. PMC 5309147. PMID 28072601.

- 1 2 3 Gauvin, France; Robitaille, Nancy (February 2020). "Diagnosis and management of transfusion‐associated circulatory overload in adults and children". ISBT Science Series. 15 (1): 23–30. doi:10.1111/voxs.12531. ISSN 1751-2816. S2CID 209246744.

- ↑ Menis, M.; Anderson, S. A.; Forshee, R. A.; McKean, S.; Johnson, C.; Holness, L.; Warnock, R.; Gondalia, R.; Worrall, C. M.; Kelman, J. A.; Ball, R. (February 2014). "Transfusion-associated circulatory overload (TACO) and potential risk factors among the inpatient US elderly as recorded in Medicare administrative databases during 2011". Vox Sanguinis. 106 (2): 144–152. doi:10.1111/vox.12070. PMID 23848234. S2CID 206353348.

- 1 2 DeLoughery, Thomas. "Thomas DeLoughery M.D.'s Famous Handouts". Retrieved November 3, 2021.

- 1 2 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (March 2021). "National Healthcare Safety Network Biovigilance Component Hemovigilance Module Surveillance Protocol" (PDF). N/A. 2.6: 9.

- ↑ Popovsky, M. A. (September 2006). "Transfusion-related acute lung injury and transfusion-associated circulatory overload". ISBT Science Series. 1 (1): 107–111. doi:10.1111/j.1751-2824.2006.00046.x. S2CID 71796205.

- ↑ Skeate, Robert C; Eastlund, Ted (November 2007). "Distinguishing between transfusion related acute lung injury and transfusion associated circulatory overload". Current Opinion in Hematology. 14 (6): 682–687. doi:10.1097/MOH.0b013e3282ef195a. PMID 17898575. S2CID 8536719.

- ↑ Goyal A, Cusick AS, Bansal P. Peripheral Edema. [Updated 2021 Jul 4]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2021 Jan-. Available from:

- ↑ Semple, John W.; Rebetz, Johan; Kapur, Rick (2019-04-25). "Transfusion-associated circulatory overload and transfusion-related acute lung injury". Blood. 133 (17): 1840–1853. doi:10.1182/blood-2018-10-860809. ISSN 0006-4971. PMID 30808638. S2CID 73506897.

- ↑ Maynard K. Administration of Blood Components. In: Technical Manual, 18th edition, Fung MK, Grossman BJ, Hillyer CD, et al (Eds), AABB, 2014.

- ↑ Raval, J. S.; Mazepa, M. A.; Russell, S. L.; Immel, C. C.; Whinna, H. C.; Park, Y. A. (May 2015). "Passive reporting greatly underestimates the rate of transfusion-associated circulatory overload after platelet transfusion". Vox Sanguinis. 108 (4): 387–392. doi:10.1111/vox.12234. PMID 25753261. S2CID 13158172.

- ↑ Clifford, Leanne; Jia, Qing; Yadav, Hemang; Subramanian, Arun; Wilson, Gregory A.; Murphy, Sean P.; Pathak, Jyotishman; Schroeder, Darrell R.; Ereth, Mark H.; Kor, Daryl J. (January 2015). "Characterizing the Epidemiology of Perioperative Transfusion-associated Circulatory Overload". Anesthesiology. 122 (1): 21–28. doi:10.1097/ALN.0000000000000513. PMC 4857710. PMID 25611653.

- ↑ "Fatalities Reported to FDA Following Blood Collection and Transfusion Annual Summary for Fiscal Year 2015". FDA. Retrieved July 17, 2017.

- ↑ Plummer, N. S. (1936-12-12). "Blood Transfusion: A Report of Six Fatalities". BMJ. 2 (3962): 1186–1189. doi:10.1136/bmj.2.3962.1186. ISSN 0959-8138. PMC 2458995. PMID 20780324.

- ↑ Popovsky, M. A.; Audet, A. M.; Andrzejewski, C. (1996). "Transfusion-associated circulatory overload in orthopedic surgery patients: a multi-institutional study". Immunohematology. 12 (2): 87–89. doi:10.21307/immunohematology-2019-753. ISSN 0894-203X. PMID 15387748. S2CID 23196802.