| Trinity Centre | |

|---|---|

| |

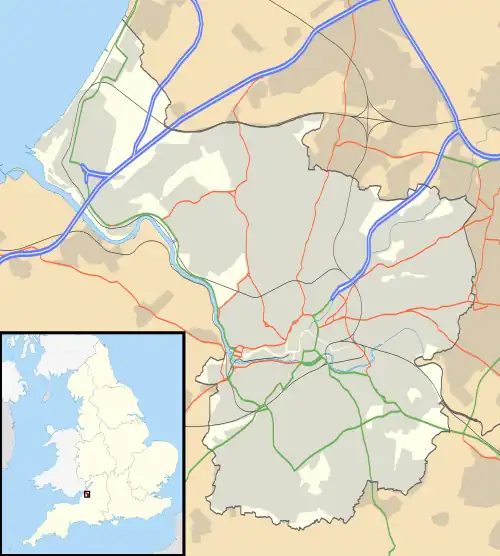

Location within Bristol | |

| General information | |

| Town or city | Bristol |

| Country | England |

| Coordinates | 51°27′29″N 02°34′34″W / 51.45806°N 2.57611°W |

| Construction started | 1829 |

| Completed | 1832 |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect(s) | Thomas Rickman and Henry Hutchinson |

The Trinity Centre is a community arts centre and independent live music venue.The building has been managed by Trinity Community Arts Ltd. since 2003 and was formerly the Holy Trinity Church, in the Parish of St Philip and St Jacob, Bristol, UK.

Trinity Community Arts Ltd

Trinity Community Arts is an arts charity[1] formed in 2002 to manage the Trinity Centre. The charity stages arts and community events and activities in the venue, including hosting space for Black creatives[2] and at citywide events including Bristol Harbour Festival.

The charity is continuing to the venue's tradition as a community arts hub, offering a diverse programme of activities. The venue is frequently cited as one of the best live music venues in the Bristol area.[3]

The charity has undertaken several phases of repair and renovation to the building, including a series of structural repairs to the historic fabric, completed after an appeal to save the venue in 2018.[4] Works were funded by Historic England. Other projects undertaken have included construction of recording studios into first floor naves and installation of a new lift and extensive refurbishment works of the first floor and creation of a new reception area.[5]

Holy Trinity Church

The former Holy Trinity Church is a grade II* listed building first listed in 1959.[6]

In 1818, £1,000,000 was given by Parliament to build new churches across the country from the spoils of the recent war against France. In 1824, a further £500,000 was given to continue with the mass build of new churches around the country, of which the Holy Trinity Church is one. These acts became known as the 'Million' and 'Half Million' Acts. Churches built as a result of these acts became known as 'Million', 'Half Million', or Waterloo churches.

The church was built between 1829 and 1832 by Thomas Rickman and Henry Hutchinson,[7] two architects from Birmingham, who also designed the piers, perimeter walls and railings which are also listed.[8]

The church is built using Bath stone in a Perpendicular style, a style of English Gothic architecture characterised by its strong emphasis on the vertical elements and its linear design.[9]

£6,000 was given to the out parish of St Philip's with a further £2,200 raised by the laymen. This and other sources brought the total cost of the build to £9,020 19s. 4d.[10] The foundation stone was laid on 22 September 1829, by the Lord Mayor John Cave and the church took 26 months to complete.

During this time, the 1831 Bristol riots took place across the city as a response to opposition of the Reform Act. The incumbent Bishop R. Gray is a very vocal opponent of the act which will give a wider range of poor and uneducated people the right to vote. As a result his palace was burned to the ground and Trinity, a symbol of wealth and opulence in a poverty-stricken area, narrowly escaped the same fate. The riots lasted three days during which a number of people died and an even greater number imbibed vast quantities of alcohol. The uprising came to a head in Queen Square, Bristol when the military charged the drunken rioters.

With construction completed, on 17 February 1832 construction the consecration ceremony took place by the Bishop of Bristol.[11] Also in attendance were the Lord Mayor Daniel Stanton, Alderman Hilhouse and the Sheriff Mr Lax. Although the church is deemed to have a "…chaste and simple beauty...", more importantly it will add significantly to "the improvements which may be expected to result in the morals and conduct of the humbler classes of that neighbourhood...".

Subsequent building works were carried out on the building circa 1882 by John Bevan and in 1905 by William Venn Gough.[12]

The church has two octagonal bell towers with open turrets on the west face of the building.[10] The towers sit on either side of the main entrance and the west window. During a period when the building sat empty, the bells were removed and either sold for scrap or to another church. The original bells and fittings were replaced with new ones in April 1927. The work was carried out by local firm Llewellins & James Ltd of Castle Green. It cost £47 10s for the bells and labour although an additional £3 10s was incurred when the workmen realised that they had to remove the floor of the towers to get the new bells in.

The original bells and fittings were replaced with new ones in April 1927. The work was carried out by local firm Llewellins & James Ltd of Castle Green. It cost £47 10s for bells and labour although an additional £3 10s was incurred when the workmen realised that they had to remove the floor of the towers to get the new bells in.[13]

The Holy Trinity Church had 2,200 seats with 1,500 of these being free.[10]

Graveyard

Due to the relatively small size of Trinity's graveyard, when graves were dug, they were dug deep and coffins were stacked on top of each other to maximise the use of space.[14]

When the church was deconsecrated the coffins were exhumed and moved to other graveyards such as Arnos Vale Cemetery.

Local context

In the 19th Century there was no provision for street lighting or for constables to patrol after dark. Hand-in-hand with this went crime. Attempts to curb crime by making the death penalty a mandatory sentence for even the smallest capital felony had little perceived impact. Local authorities felt the way to address the problem was to engage the spiralling population in Christian worship, and the Holy Trinity Church was built.[15]

On 24 April 1869, policeman PC Richard Hill 273 was stabbed to death by 19-year-old local labourer William Pullin.[16]

Thousands of people turned up to his funeral at Trinity, lining the streets all the way from the church to the burial at Arnos Vale. Pullin would have hanged had it not been for the intervention of more than 7,000 individuals petitioning for mercy on his behalf, on the grounds that he was a young man of good nature who had come to this terrible act due to circumstance.[17]

A marble memorial tablet that once resided in the Holy Trinity Church can now be found in the foyer of Old Market's Trinity Road police station, which reads: In memory of Richard Hill, police constable of this city, who was murdered whilst in the execution of his duty in Gloucester Lane, 24 April 1869, aged 31 years, and was interred in Arnos Vale Cemetery. This tablet was erected as a mark of esteem by his brother officers and inhabitants of the city. A brave man: PC Richard Hill was not forgotten.

Archives

Parish records for Holy Trinity church, St Philip's, Bristol are held at Bristol Archives (Ref. P.HT) (online catalogue) including baptism, marriage and burial registers. The archive also includes records of the incumbent, vestry, parochial church council, churchwardens, charities, Easton Christian Family Centre, schools and societies plus photographs.

Change of use

The parish of Holy Trinity was formed in 1834, from the parish of St Philip & St Jacob.[18] The Holy Trinity Church had between 1,850 and 2,200 seats with 1,500 of these being free.[19]

Due to the large size of the congregation and relatively small size of Trinity's graveyard, when graves were dug, they were dug deep and coffins were stacked on top of each other to maximise the use of space.[20] When the church was deconsecrated the coffins were exhumed and moved to other graveyards such as Arnos Vale Cemetery.

On 14 March 1966 the Diocesan Pastoral Committee decided that it should aim to create one parish, rather than two, for the Easton Comprehensive Development Area. This meant that the benefices and parishes of Holy Trinity, St Philip and St Gabriel, Easton, were to be united. As St Gabriel's was seen to be more strategically placed than Trinity, this meant that it would eventually be declared redundant.[21]

The last wedding ceremony held at the centre prior to this was on 20 March 1976, two weeks before its closure at the Holy Trinity Church on 6 April 1976,[22] though the occupiers Trinity Community Arts gained a licence in 2014 to perform civil ceremonies under the Civil Partnership Act of 2004.

Bristol Caribbean Community Enterprise Limited

Discontent amongst black and minority ethnic young people escalated due to unemployment and increasing clashes with the police.[23] Local leaders looking to ease tensions agreed for Trinity to be deconsecrated and given to the public, for use as a community centre, with a focus on activities for young people.[23]

On 19 January 1977, a sale price of £25,000 was agreed for Holy Trinity to Bristol Caribbean Community Enterprise Limited 1The purchasers were also expected 'to pay a substantial part of the purchase price and to have undertaken the conversion of the existing building before embarking on the levelling out of the churchyard.'

On 21 December 1977 an Order in Council came into operation from The Church Commissioners, allowing Holy Trinity building and its land to be used as a community centre. This covenant has influenced much of the building's recent use as an arts and community venue. The Commissioners were now empowered to sell the church and land for this use.[21]

The group take over management and 1 July 1978, the same day as St Paul's Festival, now called Carnival, Trinity Community Centre was opened to the public.[24] The group began to stage a programme of community events alongside music events, under the management of community leader, Fitzroy (Roy) de Freitas.

The sale of the building was eventually completed on 31 December 1981 with a number of restrictive covenants, including stipulating its use for community purposes. The building was purchased for £25,000 with a loan from Midland Bank.

At this time, the venue underwent several names including Trinity Hall and the Trinity Institute. These early years as a community centre and music venue were set against a backdrop of rising local tensions, culminating in the 1981 St. Pauls riot.

During the early part of the 1980s, the Centre provided a much-needed outlet for local youth culture, hosting nights of dub and reggae from the likes of Jah Shaka and Quaker City, and playing host to some of the biggest domestic and international music stars of the time, notably from the punk and new wave genres, such as U2,[25] Crass, The Cramps, Echo and the Bunnymen, Joy Division and New Order alongside local favourites such as The Stingrays and Disorder.

As a music venue, Trinity was a melting pot for the different styles popular at the time, from reggae through ska to punk. From this came a post-punk scene which blended many of these influences. Trinity saw regular performances from local acts such as Mark Stewart and The Pop Group, who through their collaborations with artists and producers from the reggae scene, as well as artists such as On-U Sound System and Gary Clail laid the foundations for the later trip hop genre, known as the "Bristol Sound".

The group had ambitions to renovate the Centre and in 1977 architect George Ferguson produces a design showing plans to split the venue into two levels.

In April 1983 Roy De Freitas is forced to resign facing accusations of financial mismanagement. However the reality was that the building was in much need of repair. Chairman Richard Davis, said "we had several months' work to do on improving the appearance of the place...it's tragic and we feel very bad about it all.[25] He believed they could turn their losses around but needed to overcome the drawbacks, such as the gravestones outside the road widening and the state of the building, which were thought responsible for people's reluctance to use the place. "We inherited a lot of problems. It's been a long, hard slog and it seems everything's been against us".

Facing debts of more than £100,000, the Inland Revenue brought legal action against Bristol Caribbean Community Enterprise Limited and on 20 December 1984 Bristol County Court put Trinity into the hands of the Official Receiver and the building was repossessed by Midland Bank as the company's biggest creditor.

Allegations that de Freitas had embezzled funds and fled to Jamaica were rife, though it eventually transpired that he was living with his sister in Clevedon, having sold his own house to invest in a cafe for the centre, which he had hoped would help to pay off Trinity's debts.[26]

The freehold was subsequently purchased by Bristol City Council on 6 June 1985, which embarked on plans to convert Trinity into a community centre for keep fit, music & dancing, meeting and function rooms. Planning consent is granted 6 April 19872 and subsequently a period of intensive refurbishment between 1987-1989, which included the splitting of the building into two levels and the removal of many of the remaining internal features of the church, including the organ.

New Trinity Community Association

The New Trinity Community Centre was put out to tender by Bristol City Council and was taken on by the New Trinity Community Association in 1991. The new tenants and a dedicated team of volunteers began a further round of development and renovations, including the installation of the sprung wooden floor downstairs and new railings[21]

The Centre reopened on 23 January 1993, and under this new management Trinity again gained international fame as an important landmark in the globally exported Bristol Sound, prominent during this era, playing host to local acts such as Roni Size, Smith & Mighty and Portishead.

As well as the successful music nights there were also daytime community activities. From bingo madness to a boxing club the two levels provided a much-needed space for everyone to use.

Shifting funds away from community centres towards Millennium Projects coupled with a series of financial problems, echoing those which led to the demise of the previous group, Trinity was forced to close once again in 2000.

Following the liquidation of the New Trinity Community Association in 2001, Bristol City Council held a tendering process for the future management of The Trinity Centre. Following this, Trinity Community Arts Ltd was constituted in 2002 and the group took on management of the Centre in 2003, reopening to the public in 2004. Trinity Community Arts Ltd registered as a charity in November 2011 and secured a 35 year leasehold from Bristol City Council in 2013.

See also

References

- ↑ Bristol Life Awards, winner in the 2021 Arts category: https://www.bristollifeawards.co.uk/categories

- ↑ Bristol space for Black creatives explores racial identity, BBC Bristol, 26 January 2022, https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-bristol-60090589

- ↑ Bristol Harbour Festival 2022: 10 things not to miss, Bristol Live, 13 July 2022, https://www.bristolpost.co.uk/whats-on/whats-on-news/bristol-harbour-festival-2022-10-7321554

- ↑ Huge appeal launched to save iconic Bristol music venue the Trinity Centre, Bristol Live, 26 January 2018 https://www.bristolpost.co.uk/whats-on/music-nightlife/huge-appeal-launched-save-iconic-1126090

- ↑ GCP Chartered Architects project page for The Trinity Centre, Bristol https://www.gcparch.co.uk/trinity-arts-centre

- ↑ National Heritage List for England, Historic England, List Entry Number 1282076, https://historicengland.org.uk/listing/the-list/list-entry/1282076

- ↑ "Holy Trinity Church". Historicengland.org.uk. Retrieved 16 March 2007.

- ↑ "Piers, perimeter walls and railings". Historicengland.org.uk. Retrieved 26 February 2009.

- ↑ Chilcott, John, Chilcott's Stranger's Guide to Bristol, 1859

- 1 2 3 Pryce, George: A Popular History Of Bristol, 1861

- ↑ Chilcott, John, Chilcott's Descriptive History of Bristol, Ancient and modern, 1851

- ↑ "HOLY TRINITY CHURCH, non Civil Parish - 1282076 | Historic England".

- ↑ "Bristol - Church of Holy Trinity, St.Philip's".

- ↑ John Latimer, Annals of Bristol in the 19th Century, 1887

- ↑ Bishop, Ian S, Stories from St.Phillip's (ISBN 0-9526490-9-8), 2002

- ↑ Nicola Sly, Bristol Murders (Sutton True Crime History), 2008 ISBN 978-0-7509-5048-0

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2 December 2008. Retrieved 10 March 2009.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ↑ 1

- ↑ 4

- ↑ 6

- 1 2 3 2

- ↑ 18

- 1 2 11

- ↑ 12

- 1 2 13

- ↑ 14