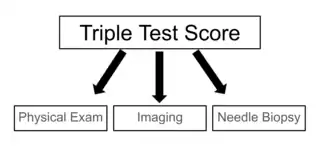

The triple test score is a diagnostic tool for examining potentially cancerous breasts. Diagnostic accuracy of the triple test score is nearly 100%. Scoring includes using the procedures of physical examination, mammography and needle biopsy. If the results of a triple test score are greater than five, an excisional biopsy is indicated.[1]

The term triple test scoring (TSS) was first noted in 1975 as a means of rapidly diagnosing and examining breast malignancies.[2] TSS developed as a useful and accurate clinical tool for breast masses because it was cheaper and it cut down on the diagnosis time.

Scoring

To obtain the triple test score, a number from 1 through 3 is assigned to each one of the procedures. A score of 1 is assigned to a benign test result, 2 applies to a suspicious test result, and 3 applies to a malignant result. The sum of the scores of all three procedures is the triple test score.

If the total summed score from the three tests is 3 to 4 then the diagnosis is most likely benign. A total summed score of 5 is considered suspicious. A score of 6 or greater is possibly malignant. There have been different inclusions for the components of the triple test score in the past, such as using the procedures of physical examination, mammography, and cytology. Other versions of the triple test score have included mammography, ultrasound, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).[3]

| Summed total score | Diagnosis |

|---|---|

| 3-4 | Benign |

| 5 | Suspicious |

| 6 < | Malignant |

TTS vs. Modified TTS (mTTS)

The TTS was first implemented and then changed to create a modified TTS. The main difference between the two diagnostic tools is the substitution of the mammogram for the ultrasound in persons under the age of 40.[4][5] This is because ultrasound has been found to be more effecting at early detection of breast cancer and masses for persons with denser breast tissues. These individuals with denser breast tissues have also been found to be at an increased risk of developing breast cancer.[6] Most modified TTS exams contain a combination of physical examination, ultrasound, and needle biopsy.[7] There are no changes to the scoring system of the mTSS.

TTS vs. BI-RADS

Like the triple test score, BI-RADS (breast imaging-reporting and data system) uses a similar method of scoring breast imaging reports to help with evaluating and determining treatment for breast masses.[8] Like the triple test score, BI-RADS employs a numerical scoring system to determine whether a mass is benign or malignant. The triple test score assigns a numerical indicator of 1 to 3 while BI-RADS assigns a numerical indicator of 1 to 6. The BI-RADS scoring for mammograms can be comparable to the triple test score's scoring for mammograms.[2] For instance, a BI-RADS of 1 or 2 is equivalent to a triple test score of 1. Similar to the triple test score, a lower scoring on BI-RADS (i.e. 1 or 2) is indicative of a benign screening while a high scoring (i.e. 5 or 6) is indicative of malignancy.[2]

Unlike the triple test score which scores three different exams, BI-RADS focuses on evaluating findings from one exam: mammograms.

Cost

The triple test score reduces cost for evaluating breast masses compared to traditional methods due to reducing the likelihood of people undergoing an excisional biopsy while still providing effective diagnoses.[2] An excisional biopsy can be performed to remove a palpable breast mass. Because of the triple test score's high accuracy, it can be used to replace excisional biopsy if all three portions of the triple test score are scored a 1 (benign), indicating that the mass does not necessarily need to be removed.[9] Cost differences between the traditional methods and the triple test score varied based on the stages of breast mass evaluation. Traditional methods of evaluating breast masses include radiological assessments (e.g. mammography, ultrasound, MRI) and pathologic analyses (e.g. fine-needle aspiration cytology, core biopsy).[10] During early work-up stages to evaluate suspicion of a breast mass—such as mammography imaging due to a palpable mass—triple test score was found to cost more than traditional methods. During diagnosis of malignancy, triple test score was found to cost less than traditional methods.[11]

Components of TTS

Physical exam

A physical exam of the breast is one of the three tests that is scored that is a part of a triple test score.[12] A clinical breast examination (CBE) is different from a breast self-exam because a CBE is conducted by a physician during an appointment whereas a self-exam is recommend to be conducted monthly by patients at home. The physician will ask the patient to stand in various poses during a CBE because this will allow them to look for abnormalities that may be present in a patient's breast.[13] An overview of 11 different systemic reviews summarized the effectiveness of a clinical breast examination as the sole method of screening for breast cancer by using sensitivity, specificity and positive predictive value as measures of accuracy. A total of 8 out of 11 reviews reported a sensitivity range between 40% and 69% which when averaged gave a result of 54.1%.[14]

Imaging

Various imaging tests can be conducted, such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), ultrasound, or mammogram, as one of the three tests that is scored that is a part of a triple test score.[15]

- An MRI can help detect malignancy with the use of contrast to help make the malignant lesions more pronounced. The sensitivity of an MRI ranges from 85–100% but the specificity ranges from 47–67%.[12]

- An ultrasound can detect abnormalities in the breast tissue by using high-frequency sound waves that bounce off the tissue that then transform into images that can be interpreted. It has been shown to be more useful in searching for masses in dense breast tissue.[16] Ultrasounds have a sensitivity of 76% and specificity of 84%.[17]

- A mammogram is done via an X-ray machine that the patient stands against and places their breast firmly on top of a specific plate while another plate presses the breast from the top while the imaging is done.[18] Mammograms have a sensitivity range of 75–85% but that range does not apply to patients with dense or small breasts.[17]

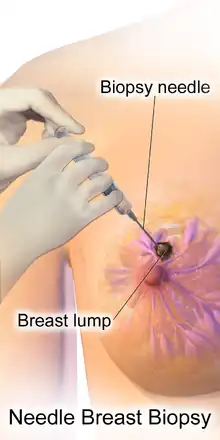

Fine-needle aspiration biopsy

Over a review of 46 studies using sensitivity, specificity, and other measures of accuracy, fine-needle aspiration biopsy proved to be a very accurate yet minimally invasive diagnostic method for evaluating breast malignancy. With the exclusion of unsatisfactory samples, fine-needle aspiration biopsy sensitivity proportion was 0.927 and the specificity proportion was 0.948. In the unsatisfactory samples, the pooled sensitivity proportion was 0.920, and the pooled specificity proportion was 0.768.[19]

One way that fine-needle aspiration biopsy cytology is reported is via the International Academy of Cytology (IAC) Yokohama System, which "defines five categories for reporting breast cytology, each with a clear descriptive term for the category, a definition, a risk of malignancy (ROM) and a suggested management algorithm."[20] This suggested management algorithm may be particularly useful in countries utilizing the triple test score, as it can provide various management strategies based on the breast lesions from fine-needle aspiration biopsy.[20]

In another review of 22 studies with over 10,000 subjects, using the IAC Yokohama Reporting System, fine-needle aspiration showed strong overall accuracy. "Sensitivity and specificity, with 95% confidence intervals, were 0.978 [0.968, 0.985] and 0.832 [0.76, 0.886] for the diagnostic cut-off of "Atypical considered positive for malignancy," 0.916 [0.892, 0.935] and 0.983 [0.97, 0.99] for the cut-off of "Suspicious of Malignancy considered positive," and 0.763 [0.706, 0.812] and 0.999 [0.994, 1] for the cut-off of "Malignant considered positive."[21]

The IAC Yokohama Reporting System was also evaluated on the pooled risk of malignancy in a meta analysis of 18 different studies with a total of 7,969 cases. They found that when considering both "suspicious" and "malignant" as positive results, the sensitivity was 91%, and the false positive rate was 2.33%.[22]

Overall, fine-needle aspiration cytopathology can greatly benefit low medical infrastructure communities as it is "minimally invasive and well-tolerated by patients, inexpensive, and requires minimal laboratory infrastructure and proceduralist costs." However, two major requirements that may slow the integration of fine-needle aspiration cytology is actually attaining or training pathologists and to encourage the use cytopathology in the education of local clinicians.[23]

Use today

Studies investigating the applicability and the effectiveness of the triple test score in the United States have ranged from the 1991 to 2010.[1][24][9] The current prevalence and usage of the triple test score in the United States are not well understood.

In the United Kingdom, the triple test score is usually referred to as the "triple assessment". The majority of hospitals in the UK have implemented rapid-access breast cancer screening clinics where the triple test score is used as a clinical diagnostic tool.[25][26]

Ongoing research efforts are essential for the long-term effectiveness and applicability of the triple test score in healthcare settings.

Reframing guidelines

Breast cancer is not a gender-specific disease; anyone who has breast tissue has a risk of getting breast cancer. Gendering guidelines for breast cancer excludes individuals who do not identify as female, which can potentially lead to late detection of breast cancer in those individuals. There has been a push by various healthcare providers to make guidelines more inclusive when it comes to breast cancer screenings and awareness.[27]

References

- 1 2 Morris A, Pommier RF, Schmidt WA, Shih RL, Alexander PW, Vetto JT (September 1998). "Accurate Evaluation of Palpable Breast Masses by the Triple Test Score". Archives of Surgery. 133 (9): 930–934. doi:10.1001/archsurg.133.9.930. PMID 9749842.

- 1 2 3 4 Johnsén C (1975-01-01). "Breast disease. A clinical study with special reference to diagnostic procedures". Acta Chirurgica Scandinavica. Supplementum. 454: 1–108. PMID 1059305.

- ↑ Egyed Z, Járay B, Kulka J, Péntek Z (28 August 2008). "Triple test score for the evaluation of invasive ductal and lobular breast cancer". Pathology & Oncology Research. 15 (2): 159–166. doi:10.1007/s12253-008-9083-3. PMID 18752055. S2CID 6523239.

- ↑ Harvey JA (August 2006). "Sonography of Palpable Breast Masses". Seminars in Ultrasound, CT, and MR. Breast Imaging Update. 27 (4): 284–297. doi:10.1053/j.sult.2006.05.003. PMID 16915997.

- ↑ Morris KT, Vetto JT, Petty JK, Lum SS, Schmidt WA, Toth-Fejel S, Pommier RF (October 2002). "A new score for the evaluation of palpable breast masses in women under age 40". American Journal of Surgery. 184 (4): 346–347. doi:10.1016/S0002-9610(02)00947-9. PMID 12383898.

- ↑ Thigpen D, Kappler A, Brem R (March 2018). "The Role of Ultrasound in Screening Dense Breasts-A Review of the Literature and Practical Solutions for Implementation". Diagnostics. 8 (1): 20. doi:10.3390/diagnostics8010020. PMC 5872003. PMID 29547532.

- ↑ Kachewar SS, Dongre SD (2015). "Role of triple test score in the evaluation of palpable breast lump". Indian Journal of Medical and Paediatric Oncology. 36 (2): 123–127. doi:10.4103/0971-5851.158846. PMC 4477375. PMID 26157290.

- ↑ Magny SJ, Shikhman R, Keppke AL (August 29, 2022). "Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System". StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. PMID 29083600. Retrieved 2023-07-30.

- 1 2 Morris KT, Pommier RF, Morris A, Schmidt WA, Beagle G, Alexander PW, et al. (September 2001). "Usefulness of the triple test score for palpable breast masses; discussion 1012-3". Archives of Surgery. 136 (9): 1008–1012. doi:10.1001/archsurg.136.9.1008. PMID 11529822. S2CID 22625052.

- ↑ Daly C, Puckett Y (August 1, 2022). "New Breast Mass". StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. PMID 32809592. Retrieved 2023-07-29.

- ↑ Morris AM, Flowers CR, Morris KT, Schmidt WA, Pommier RF, Vetto JT (August 2003). "Comparing the cost-effectiveness of the triple test score to traditional methods for evaluating palpable breast masses". Medical Care. 41 (8): 962–971. doi:10.1097/00005650-200308000-00009. PMID 12886175. S2CID 41315487.

- 1 2 Klein S (May 2005). "Evaluation of palpable breast masses". American Family Physician. 71 (9): 1731–1738. PMID 15887452.

- ↑ "Clinical Breast Exam". National Breast Cancer Foundation. Retrieved 2023-07-30.

- ↑ Ngan TT, Nguyen NT, Van Minh H, Donnelly M, O'Neill C (November 2020). "Effectiveness of clinical breast examination as a 'stand-alone' screening modality: an overview of systematic reviews". BMC Cancer. 20 (1): 1070. doi:10.1186/s12885-020-07521-w. PMC 7653771. PMID 33167942.

- ↑ "The Triple Test". www.breastcancerfoundation.org.nz. Retrieved 2023-07-30.

- ↑ Sood R, Rositch AF, Shakoor D, Ambinder E, Pool KL, Pollack E, et al. (August 2019). "Ultrasound for Breast Cancer Detection Globally: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis". Journal of Global Oncology. 5 (5): 1–17. doi:10.1200/JGO.19.00127. PMC 6733207. PMID 31454282.

- 1 2 Chen HL, Zhou JQ, Chen Q, Deng YC (July 2021). "Comparison of the sensitivity of mammography, ultrasound, magnetic resonance imaging and combinations of these imaging modalities for the detection of small (≤2cm) breast cancer". Medicine. 100 (26): e26531. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000026531. PMC 8257894. PMID 34190189.

- ↑ "What Is a Mammogram?". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2022-09-26. Retrieved 2023-07-30.

- ↑ Yu YH, Wei W, Liu JL (January 2012). "Diagnostic value of fine-needle aspiration biopsy for breast mass: a systematic review and meta-analysis". BMC Cancer. 12: 41. doi:10.1186/1471-2407-12-41. PMC 3283452. PMID 22277164.

- 1 2 Field AS, Raymond WA, Rickard M, Arnold L, Brachtel EF, Chaiwun B, et al. (2019). "The International Academy of Cytology Yokohama System for Reporting Breast Fine-Needle Aspiration Biopsy Cytopathology". Acta Cytologica. 63 (4): 257–273. doi:10.1159/000499509. PMID 31112942. S2CID 263539317.

- ↑ Paul P, Azad S, Agrawal S, Rao S, Chowdhury N (2023). "Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Diagnostic Accuracy of the International Academy of Cytology Yokohama System for Reporting Breast Fine-Needle Aspiration Biopsy in Diagnosing Breast Cancer". Acta Cytologica. 67 (1): 1–16. doi:10.1159/000527346. PMID 36412573. S2CID 253760182.

- ↑ Nikas IP, Vey JA, Proctor T, AlRawashdeh MM, Ishak A, Ko HM, Ryu HS (February 2023). "The Use of the International Academy of Cytology Yokohama System for Reporting Breast Fine-Needle Aspiration Biopsy". American Journal of Clinical Pathology. 159 (2): 138–145. doi:10.1093/ajcp/aqac132. PMC 9891409. PMID 36370120.

- ↑ Field AS (March 2018). "Cytopathology in Low Medical Infrastructure Countries: Why and How to Integrate to Capacitate Health Care". Clinics in Laboratory Medicine. Global Health and Pathology. 38 (1): 175–182. doi:10.1016/j.cll.2017.10.014. PMID 29412881.

- ↑ Vetto J, Pommier R, Schmidt W, Wachtel M, DuBois P, Jones M, Thurmond A (May 1995). "Use of the "triple test" for palpable breast lesions yields high diagnostic accuracy and cost savings". American Journal of Surgery. 169 (5): 519–522. doi:10.1016/S0002-9610(99)80209-8. PMID 7747833.

- ↑ "Overview | Early and locally advanced breast cancer: diagnosis and management | Guidance". www.nice.org.uk. 2018-07-18. Retrieved 2023-07-26.

- ↑ Chalasani P, Stopeck AT, Thompson PA (May 2023). Kiluk JV (ed.). "Breast Cancer Workup: Approach Considerations, Breast Cancer Screening, Ultrasonography". emedicine.medscape.com. Retrieved 2023-07-30.

- ↑ "Breast Cancer Has No Gender". Cedars-Sinai. October 18, 2021. Retrieved 2023-08-02.