Tripolitanian Republic | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1918–1922 | |||||||||

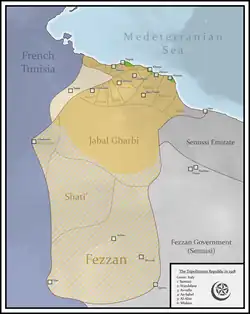

Tripolitanian Republic in orange. | |||||||||

| Capital | ʽAziziya | ||||||||

| Common languages | Arabic , Berber | ||||||||

| Religion | Islam | ||||||||

| Government | Republic (under a 4-member Supreme Council) | ||||||||

• Wali | Ramadan al-Suwayhili | ||||||||

• Wali | Sulayman al-Baruni | ||||||||

• Wali | Ahmad al-Murayid | ||||||||

• Wali | 'Abd al-Nabi Bilkhayr | ||||||||

| Historical era | Interwar period | ||||||||

• Established | November 16 1918 | ||||||||

• Disestablished | 1922 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

The Tripolitanian Republic (Arabic: الجمهورية الطرابلسية, al-Jumhuriyat at-Trabulsiya), was an Arab republic that declared the independence of Tripolitania from Italian Libya after World War I.

Background

Tripolitania had been an Ottoman possession since the 16th century, as the Tripolitania Eyalet and later Vilayet.[1] Its territory was not solely limited to Tripolitania, however, as parts of Barqa were also controlled by the Pasha of Tripoli. After Tunis and Egypt fell to the French and British respectively, Tripolitania was the last Ottoman possession in Africa. In 1912, the Kingdom of Italy launched an invasion of Tripolitania, and annexed the territory after defeating the Ottoman troops there.

The Italians did not maintain solid control of the region at first. During the Senussi Campaign of World War I, the Senussi Order led a resistance that pushed the Italian forces back to a handful of port cities. The Senussi were supported in this effort by Germany and the Ottoman Empire,[2] as well as by various local tribes and chiefdoms. It was in this context of general chaos in Northern Libya in which the Tripolitanian Republic was founded.

Independence

The proclamation of the republic in autumn 1918 was followed by a formal declaration of independence at the 1919 Paris Peace Conference.

The capital of the republic was the town of 'Aziziya, 40km south of then italian-occupied Tripoli, and its territory stretched, at its widest, from the Nafusa Mountains near the Tunisian border, to Misrata and the surrounding coast, encompassing all the hinterland between them, the only exceptions being italian-held Tripoli and Homs areas.[5]

It was governed by a tetrarchy composed of Sulayman al-Baruni, Ramadan Asswehly, Abdul Nabi Belkheir and Ahmad Almarid, although each one acted autonomous from each other, as they had significant ideological differences between them.[6] This was the first formally declared republican form of government in Libya and in the whole Arab World, but it gained little support from international powers.

Dissolution and reestablishment

The Italian colonial authorities negotiated with al-Baruni and other chiefs, publishing 1 June 1919 a Colonial Statute for Tripolitania, in which the colonial administration would give native Tripolitanians rights to Italian citizenship, recognition of the Islamic Law as the Civil Law of the colony, and provided that the colony would be governed by an Italian governor advised by a 10-member council, with 8 of those members being elected.[7]

At first, the Tripolitanian leaders were satisfied with the statute officially dissolved the Republic the 12th of July, but, when Vicenzo Garioni (the colonial governor which had negotiated with the rebel leaders) was recalled to Italy in mid-August and the new governor, Vittorio Menzinger did not seem to apply the Statute, the former rebel leaders formed the National Reform Party (Hizb al-Islam al-Watani) to exert pressure on the Italians. The main leaders of the Party were 'Azzam, al-Qarqani and al-Gharyani.[8]

However, by November, the elections for the council hadn't been celebrated, and the main leaders and chiefs of Tripolitania declared and reestablished the Republic the 16th of November in Misratah, just 4 months after being dissolved, and the establishment of a governing body: the Reform Committee.[9]

In 1920, delegates from occupied and free zones met in Aziza, on a National Congress. Claiming to represent the "Tripolitanian Nation," they called for the withdrawal of the Italian forces.

The next appointed governors, Luigi Mercatelli and Giuseppe Volpi turned to the military power to subjugate the region. The division between insurgents was getting bigger, and, after the death of al-Suwaylih in August 1920 by political opponents, the rebels started to fracture and the Republic, still in its conflict with the Italians, fell into civil war.

By early 1922, the Tripolitanians were desperate and met with Senussi delegates, offering Idris (the leader of the Senussi and Emir of Cyrenaica) the right to be the Emir of Tripolitania. Idris' acceptance, as the nationalists understood, would draw sharp Italian disapproval and be the signal for the resumption of open warfare. War with Italy, in any event, appeared likely sooner or later. For several months, Idris pondered the nationalist appeal. For whatever reason – perhaps to further the cause of total independence or perhaps out of a sense of religious obligation to resist the infidel – Idris accepted the amirate of all Libya in November and then, to avoid capture by the Italians, fled to Egypt, where he continued to guide the Sanusi order.[10]

By 1923, Italian control was effective in the territories of the Republic, which ceased to exist, but still was confined to the Tripolitanian and outer Cyrenaican areas, the rest of the country, still in the hands of the Senussi-led rebels, had yet to be conquered and pacified.

Organs

The short-lived republic only stablished two government organs: a Supreme Council, whose members formed the "governing tetrarchy" (Sulayman al-Baruni, Ramadan Asswehly, Abdul Nabi Belkheir and Ahmad Almarid) and Consultative Council consisting of twenty-four other chiefs representing various parts of Tripolitania.[11]

Further reading

- Anderson, Lisa (1982). Joffe, George; MacLachlan, Keith (eds.). "The Tripoli Republic". Social and Economic Development of Libya. Wisbeck: Menas Press. ISBN 9780906559109.

References

- ↑ Almanach de Gotha: annuaire généalogique, diplomatique et statistique. J. Perthes. 1867. pp. 827–829. Retrieved 2013-06-01.

- ↑ Zürcher, Erik-Jan (1867). Jihad and Islam in World War I. Leiden University Press. doi:10.26530/OAPEN_605452. ISBN 9789087282509. Retrieved 2022-09-01.

- ↑ http://www.hubert-herald.nl/LibyaTripoli.htm

- ↑ http://www.hubert-herald.nl/LibyaTripoli.htm

- ↑ Libya between History and Revolution: Resilience, New Opportunities and Challenges for the Berbers. UNIVERSITÀ DEGLI STUDI DI NAPOLI “L’ORIENTALE”. 2020. pp. 67–78.

- ↑ Libya between History and Revolution: Resilience, New Opportunities and Challenges for the Berbers. UNIVERSITÀ DEGLI STUDI DI NAPOLI “L’ORIENTALE”. 2020. pp. 67–78.

- ↑ A History of the Maghrib in the Islamic Period. Cambridge University Press. 1987. p. 395. ISBN 9780521337670. Retrieved 2022-01-09.

- ↑ A History of the Maghrib in the Islamic Period. Cambridge University Press. 1987. p. 395. ISBN 9780521337670. Retrieved 2022-01-09.

- ↑ Libya - Italian Rule and Arab Resistance, consulted 09-02-2022

- ↑ Libya - Italian Rule and Arab Resistance, consulted 09-02-2022

- ↑ A History of the Maghrib in the Islamic Period. Cambridge University Press. 1987. p. 395. ISBN 9780521337670. Retrieved 2022-01-09.