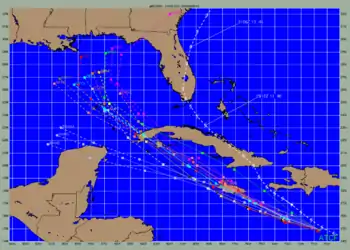

A tropical cyclone tracking chart is used by those within hurricane-threatened areas to track tropical cyclones worldwide. In the north Atlantic basin, they are known as hurricane tracking charts. New tropical cyclone information is available at least every six hours in the Northern Hemisphere and at least every twelve hours in the Southern Hemisphere. Charts include maps of the areas where tropical cyclones form and track within the various basins, include name lists for the year, basin-specific tropical cyclone definitions, rules of thumb for hurricane preparedness, emergency contact information, and numbers for figuring out where tropical cyclone shelters are open.

In paper form originally, computer programs were developed in the 1980s for personal home and use by professional weather forecasters. Those used by weather forecasters saved preparation times, allowing tropical cyclone advisories to be sent an hour earlier. With the advent of the internet in the 1990s, digitally-prepared charts began to include other information along with storm position and past track, including forecast track, areas of wind impact, and related watches and warnings. Geographic information system (GIS) software allows end users to underlay other layered files onto forecast storm tracks to anticipate future impacts.

History

Tropical cyclone tracking charts were initially used for tropical cyclone forecasting and towards the end of the year for post season summaries of the season's activity. Their use led to a north Atlantic-based term still in use today: Cape Verde hurricane. Prior to the early 1940s, the term Cape Verde hurricane referred to August and early September storms that formed to the east of the surface plotting charts in use at the time.[1] By October 1955, charts used for tropical cyclone tracking and forecasting operationally, such as United States Weather Bureau Form 770-17 and National Weather Service Chart HU-1, extended eastward to the African coast.[2]

Within the United States since at least 1956,[3] during the Atlantic hurricane season, those within threatened states were provided hurricane tracking charts in order to follow tropical storms and hurricanes during the season for situational awareness. This was more popular along sections of the southern Eastern Seaboard and Gulf Coast of the United States than the coast of California due to their increased danger of a landfalling tropical cyclone. The maps would include place names, latitude and longitude lines,[4] names of the storms on that year's list,[5] along with hurricane preparedness information.[6] Newspapers,[3] television stations,[4] radio stations,[7] banks,[4] restaurants,[8] grocery stores, insurance companies,[5] gas stations, the American Red Cross, the Federal Emergency Management Agency, state departments of emergency management,[9] the National Weather Service,[4] and its subagency the National Hurricane Center were the main suppliers of these charts. Companies would distribute these for free as they were considered good advertising.[4] Some would have a table where you could enter data prior to plotting the storm's position,[10] usually using an associated tropical cyclone symbol: open circle for tropical depression, open circle with curved lines on opposite sides of the circle for tropical storms, and a closed circle with curved lines on opposite sides of the circle for hurricanes.[11] The Vanuatu Meteorology and Geo-Hazards Department started preparing special tropical cyclone tracking charts for its archipelago in the 1980s.[12]

Initially, the charts were in paper form. Magnetic charts appeared in 1956.[13] By 1974, laminated paper was used, and by 1977 maps were placed under glass,[4] so that grease pencil, washable marker, or dry erase marker could be used and that the map could be used for multiple seasons.[14] Starting in the 1980s with the increasing popularity of personal computers, programs were available to track the storms digitally,[15] and databases of past storms could be maintained. However, computational space requirements did not allow access to the entire hurricane database for a related basin until the 1990s, with the advent of more powerful computers with megabytes of storage and file quantities became less limited in computer directory structures. Starting in the mid 1990s, with the popularity of the World Wide Web, web sites kept images of old hurricane tracks and interactive web sites allowed you to specify parameters for the storms you wished to display.[16] Ongoing storms have tracking charts with forecast track overlaid.[17] Since 2004, GIS software has been available for hurricane tracking.[18]

Move away from paper use operationally

Historically, tropical cyclone tracking charts were used to include the past track and prepare future forecasts at Regional Specialized Meteorological Centers and Tropical Cyclone Warning Centers. The need for a more modernized method for forecasting tropical cyclones had become apparent to operational weather forecasters by the mid-1980s. At that time the United States Department of Defense was using paper maps, acetate, grease pencils, and disparate computer programs to forecast tropical cyclones.[19] The Automated Tropical Cyclone Forecasting System (ATCF) software was developed by the Naval Research Laboratory for the Joint Typhoon Warning Center (JTWC) beginning in 1986,[20] and used since 1988. During 1990 the system was adapted by the National Hurricane Center (NHC) for use at the NHC, National Centers for Environmental Prediction and the Central Pacific Hurricane Center.[20][21] This provided the NHC with a multitasking software environment which allowed them to improve efficiency and cut the time required to make a forecast by 25% or 1 hour.[21] ATCF was originally developed for use within DOS, before later being adapted to Unix and Linux.[20] Despite ATCF's introduction, into the late 1990s, a National Hurricane Center forecaster stated that the most important tools available were "a pair of dividers to measure distance, a ruler, a brush for eraser dirt, three sharp pencils colored red, black, and blue, and a large paper plotting chart".[22]

Markings used

Symbols used within the charts vary by basin, by center, and by individual preference. Simple dots or circles can be used for each position. The National Hurricane Center uses a variety of symbols composed of overlapping 6's and 9's for tropical storms and hurricanes to emulate their circulation pattern, and a circle for tropical depressions.[23] Other Northern Hemisphere centers used the overlapping 6 and 9 symbols for all tropical cyclones of tropical storm strength, with L's reserved for tropical depressions or general low pressure areas in the tropics. Southern Hemisphere versions would use backward overlapping 6's and 9's. The World Meteorological Organization uses an unfilled symbol to depict tropical storms, a filled symbol to depict systems of cyclone/hurricane/typhoon strength, and a circle to depict a tropical low or tropical convective cluster.[24] Colors of the symbols may be representative of the cyclone's intensity.[25]

Lines or dots connecting symbols can be varying colors, solid, dashed, or symbols between the points depending on the intensity and type of the system being tracked.[26] Different colors could also be used to differentiate storms from one other within the same map.[27] If black and white markings are used, tropical depression track portions can be indicated by dots, with tropical storms indicated by dashes, systems of cyclone/hurricane/typhoon strength using a solid line, intermittent triangles for the subtropical cyclone stage, and intermittent plus signs for the extratropical cyclone phase.[28] Systems of category 3 strength or greater on the Saffir–Simpson scale can be depicted with a thicker line.[29]

Sources of information

In order to use a hurricane tracking chart, one needs access to latitude/longitude pairs of the cyclone's center and maximum sustained wind information in order to know which symbol to depict. New tropical cyclone information is available at least every twelve hours in the Southern Hemisphere and at least every six hours in the Northern Hemisphere from Regional Specialized Meteorological Centers and Tropical Cyclone Warning Centers.[30][31][32][33][34]

In decades past, newspaper, television, and radio (including weather radio) were primary sources for this information. Local television stations within threatened markets would advertise tropical cyclone positions within the morning, evening, and nightly news during their weather segments. The Weather Channel includes the information within their tropical updates every hour during the Atlantic and Pacific hurricane seasons. Starting in the mid 1990s, the World Wide Web allowed for the development of ftp and web sites by the Bureau of Meteorology in Australia,[35] Canadian Hurricane Centre,[36] Central Pacific Hurricane Center,[37] the Nadi Tropical Cyclone Centre/Fiji Meteorological Service,[38] Japan Meteorological Agency,[39] Joint Typhoon Warning Center,[40] Météo-France La Réunion, National Hurricane Center,[33] and the Philippine Atmospheric, Geophysical and Astronomical Services Administration which allows the end user to get their information from their official products.[41]

Use

The maps either use a mercator projection if restricted to the tropics and subtropics, but can use a Lambert conformal conic projection if the maps reach towards the arctic for the North Atlantic basin where tropical cyclones move more poleward. Meteorologists use these maps to estimate a system's initial position based on aircraft, satellite, and surface data within surface weather analyses. The data is then analyzed to determine recent storm motion and create and convey forecast tracks, wind swaths, uncertainty, related watches, and related warnings to end users of tropical cyclone forecasts.

Hurricane tracking charts allow people to track ongoing systems to form their own opinions regarding where the storms are going and whether or not they need to prepare for the system being tracked, including possible evacuation. This continues to be encouraged by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and National Hurricane Center.[11] Some agencies provide track storms in their immediate vicinity,[42] while others cover entire ocean basins. One can choose to track one storm per map, use the map until the table is filled, or use one map per season. Some tracking charts have important contact information in case of an emergency or to locate nearby hurricane shelters.[9] Tracking charts allow tropical cyclones to be better understood by the end user.[43]

Hurricane tracker apps

A number of Hurricane tracker apps are also available online to install directly over a smartphone. By using these apps, one can easily track the current activity of the Hurricanes. Red Cross has also launched several applications for this purpose.[44]

References

- ↑ Gordon E. Dunn; Banner I. Miller (1960). Atlantic Hurricanes. Louisiana State University Press. p. 54. ASIN B0006BM85S.

- ↑ George W. Cry, Willam H. Haggard, and Hugh S. White (1959). Technical Paper 36: North Atlantic Tropical Cyclones Tracks and Frequencies of Hurricanes and Tropical Storms 1886-1958. United States Department of Commerce. p. 22.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - 1 2 The Corpus Christi Caller-Times (1956-07-29). "Here's the Plotting Map; Be Your Own 'Hurricane Hunter'". pp. 8B–9B.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 United Press International (1977-06-03). "Hurricane Maps Popular". Vol. 83, no. 58. Ruston Daily Leader. p. 16.

- 1 2 The Travelers Insurance Company (1957). Hurricane Information and Tracking Chart.

- ↑ Florida Division of Emergency Management (February 2011). "Hurricane Tracking Map" (PDF). Retrieved 2017-06-03.

- ↑ Navasota Examiner (1964-08-27). "Hurricane Tracking Charts Available At Radio Station". Vol. 68, no. 51. p. 3.

- ↑ Library of Congress Copyright Office (July–December 1977). "Catalog of Copyright Entries. Third Series: 1977: July–December: Index". p. 907. Retrieved 2017-06-29.

- 1 2 East Baton Rouge Parish Office of Emergency Management (2000). "East Baton Rouge Parish Hurricane Response Map" (PDF). Louisiana Section of the United States Geological Survey. Retrieved 2017-06-04.

- ↑ City of Biloxi, Mississippi (2006). "Hurricane Tracking Map" (PDF). pp. 6–7. Retrieved 2017-06-19.

- 1 2 National Ocean Service (2016-09-07). "Follow That Hurricane!" (PDF). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 2017-06-02.

- ↑ Rita Narayan (2016-07-04). "Illustrated [Beufort Scale] Vanuatu Tropical Cyclone Tracking Map". Vanuatu Meteorology and Geo-Hazards Department. Retrieved 2017-06-19.

- ↑ Panama City Herald (1956-07-31). "80: New Merchandise HURRICANE CHART". Vol. 40, no. 151. p. 14.

- ↑ Corpus Christi Times (1974-09-30). "The Trading Post". Vol. 66, no. 69.

- ↑ Climate Assessment Technology (1982). The Hurricane Tracker: Users Guide for the IBM Personal Computer.

- ↑ National Weather Service Office Brownsville, Texas. "Create Your Own Tropical Cyclone Track History" (PDF). National Weather Service. Retrieved 2017-06-17.

- ↑ National Hurricane Center. "ERIKA Graphics Archive". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 2017-06-17.

- ↑ ESRI (2004). "ArcGIS 9: Using ArcGIS Tracking Software" (PDF). TASC, Inc. Retrieved 2017-06-17.

- ↑ Ronald J. Miller; Ann J. Schrader; Charles R. Sampson & Ted L. Tsui (December 1990). "The Automated Tropical Cyclone Forecasting System (ATCF)". Weather and Forecasting. 5 (4): 653–600. Bibcode:1990WtFor...5..653M. doi:10.1175/1520-0434(1990)005<0653:TATCFS>2.0.CO;2.

- 1 2 3 Sampson, Charles R; Schrader, Ann J (June 2000). "The Automated Tropical Cyclone Forecasting System (Version 3.2)". Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. 81 (6): 1231–1240. Bibcode:2000BAMS...81.1231S. doi:10.1175/1520-0477(2000)081<1231:tatcfs>2.3.co;2.

- 1 2 Rappaport, Edward N; Franklin, James L; Avila, Lixion A; Baig, Stephen R; Beven II, John L; Blake, Eric S; Burr, Christopher A; Jiing, Jiann-Gwo; Juckins, Christopher A; Knabb, Richard D; Landsea, Christopher W; Mainelli, Michelle; Mayfield, Max; McAdie, Colin J; Pasch, Richard J; Sisko, Christopher; Stewart, Stacy R; Tribble, Ahsha N (April 2009). "Advances and Challenges at the National Hurricane Center". Weather and Forecasting. 24 (2): 409. Bibcode:2009WtFor..24..395R. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.207.4667. doi:10.1175/2008WAF2222128.1. S2CID 14845745.

- ↑ William A. Sherden (1998). The Fortune Sellers: The Big Business of Buying and Selling Predictions. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. p. 39. ISBN 978-0-471-18178-1. Retrieved 2017-08-06.

- ↑ National Hurricane Center (2017). "National Hurricane Center web site". Retrieved 2017-06-04.

- ↑ Robert P. Pearce, Royal Meteorological Society, ed. (2002). Meteorology at the Millennium. Vol. 83. Academic Press. p. 103. ISBN 978-0-12-548035-2. Retrieved 2017-06-04.

- ↑ Steven P. Sopko and Robert J. Falvey (2015). "Annual Tropical Cyclone Report 2015" (PDF). Joint Typhoon Warning Center. p. 91. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-08-16. Retrieved 2017-06-04.

- ↑ National Hurricane Center (2017). "2016 Atlantic Hurricane Tracks". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 2017-06-04.

- ↑ John Ingargiola, Clifford Oliver, James Gilpin, and Shabbar Saifee (2013-07-26). "Mitigation Assessment Team Report: Hurricane Charley in Florida. Appendix E: The History of Hurricanes in Southwest Florida" (PDF). Federal Emergency Management Agency. p. E-2. Retrieved 2017-06-04.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Richard J. Pasch, Todd B. Kimberlain, and Stacey R. Stewart (2014-09-09). "Preliminary Report Hurricane Floyd 7–17 September, 1999" (PDF). National Hurricane Center. p. 24. Retrieved 2017-06-04.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Colin J. McAidie, Christopher W. Landsea, Charles J. Newmann, Joan E. David, and Eric S. Blake (July 2009). Historical Climatological Series 6-2: Tropical Cyclones of the North Atlantic Ocean 1851–2006 (PDF). National Climatic Data Center. p. 202. ISBN 978-0-387-09409-0. Retrieved 2017-06-04.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ "Regional Specialized Meteorological Center". Tropical Cyclone Program (TCP). World Meteorological Organization. April 25, 2006. Retrieved November 5, 2006.

- ↑ Fiji Meteorological Service (2017). "Services". Retrieved 2017-06-04.

- ↑ Joint Typhoon Warning Center (2017). "Products and Service Notice". United States Navy. Retrieved 2017-06-04.

- 1 2 National Hurricane Center (March 2016). "National Hurricane Center Product Description Document: A User's Guide to Hurricane Products" (PDF). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 2017-06-03.

- ↑ Japan Meteorological Agency (2017). "Notes on RSMC Tropical Cyclone Information". Retrieved 2017-06-04.

- ↑ Bureau of Meteorology. Tropical Cyclone Advices Archived 2009-03-11 at the Wayback Machine, Bureau of Meteorology, 2009.

- ↑ Canadian Hurricane Centre (2004). Canadian Hurricane Centre's Responsibilities. Environment Canada. Retrieved on 2009-02-16. Archived May 15, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ National Weather Service Honolulu, Hawai'i (2017). "Central Pacific Hurricane Center". Pacific Region Headquarters. Retrieved 2017-06-04.

- ↑ Fiji Meteorological Service. "Fiji Meteorological Service". Retrieved 2017-06-04.

- ↑ "Japan Meteorological Agency: The national meteorological service of Japan" (PDF). Japan Meteorological Agency. Retrieved 2011-02-07.

- ↑ Joint Typhoon Warning Center. "Joint Typhoon Warning Center Mission Statement". Archived from the original on August 12, 2009. Retrieved July 17, 2013.

- ↑ Locsin, Joel (November 1, 2014). "For improved response? PAGASA to adopt 'super typhoon' category in 2015". GMA News Online. Retrieved 2 November 2014.

- ↑ Vanuatu Meteorology & Geo-Hazards Department (2017). "Vanuatu Cyclone Tracking Map". Retrieved 2017-06-04.

- ↑ Tiffany Means (2016-05-18). "How to Use a Hurricane Tracking Chart". Thought Co. Retrieved 2017-06-03.

- ↑ "Hurricane Tracker Apps".