A truss is a tight bundle of hay or straw. It would usually be cuboid, for storage or shipping, and would either be harvested into such bundles or cut from a large rick.

Markets and law

Hay and straw were important commodities in the pre-industrial era. Hay was required as fodder for animals, especially horses, and straw was used for a variety of purposes including bedding. In London, there were established markets for hay at Smithfield, Whitechapel and by the village of Charing, which is still now called the Haymarket.[1] The weight of trusses was regulated by law and statutes were passed in the reigns of William III and Mary II, George II and George III. The latter act of 1796 established the weights as follows:[2][3]

... And be it further enacted that no hay or straw whatever shall be sold in any market or place within the cities of London or Westminster, or the weekly bills of mortality, or within thirty miles thereof, other than except in what is made up in bundles or trusses; ...

... that each and every bundle or truss of hay sold in any market or place within the cities or limits aforesaid, between the last day of August in any year and the first day of June in the succeeding year, shall contain and be of the full weight of fifty-six pounds at least; and that every bundle or truss of hay sold within the cities or limits aforesaid, between the first day of June and the last day of August in any year, being new hay, of the summer's growth of that year, shall be and contain the full weight of sixty pounds, and being old hay of any former year's growth, the weight of fifty-six pounds, as aforesaid; and that each and every bundle or truss of straw sold within the cities or limits aforesaid, shall contain and be of the full weight of thirty-six pounds; and that every load of hay or straw shall contain thirty-six bundles or trusses; ...

...that the pair of bands with which any bundle or truss of hay shall be bound shall not exceed the weight of five pounds, ...

In summary then, the standard weights of a truss were:

- new hay, 60 pounds

- old hay, 56 pounds

- straw, 36 pounds

and 36 trusses made up a load.[4]

Trussing

A detailed description was provided in British Husbandry, sponsored by the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge,[5]

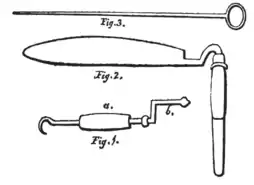

The operation of trussing is in England performed with great nicety, and is so well deserving of imitation, that a description of it cannot be considered misplaced. The cutting is commenced at that end which is the least exposed to the weather, and should be begun at the left-hand corner. The binder begins by forming "thumb-bands" of the most inferior hay for tying up the trusses; in making which he is assisted by a boy, who holds both ends of a wisp of damped hay between his hands. He then catches the wisp with the crook of an implement called in different places, a "twiner", a "throw-crook", or a "windle" which is made, like fig. 1., of a circular piece of iron about a foot and a half long, inclosed in a hollow tube of wood as at a. This he grasps with his left hand, and then turning the handle b, the crook revolves in the tube, and the band is instantaneously twisted.

This done, he measures the cut to be made in the stack, which is decided by the usual size of the trusses — each being as nearly as possible three feet by two and a half, and thick in proportion to the fineness and closeness of the hay; those of the best quality being the thinnest. He then mounts the ladder and cuts perpendicularly through the thatch, as far down as will produce the requisite number of trusses. This he does with a very strong and sharp knife, about thirty inches in length by nearly six in breadth of the blade, and formed as in fig. 2. The handle is however often made short and straight from the blade, but the form above represented allows of more power being exerted by the workman in cutting through the stack, and it is an operation which demands considerable strength.

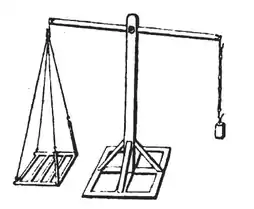

Having cut the necessary quantity, he next uses an iron spike, nearly three feet in length, with a small handle at the top, as at fig. 3. which he thrusts into the truss, and thus separates it in nearly its exact weight from the stack; afterwards laying it upon two of the bands, which have been previously stretched upon a weighing machine, of the annexed form, and furnished with a 56 lb. weight, though steelyards are sometimes used, but are not more convenient, while they are more expensive. The machine can be made by any common carpenter of a size to hold a truss of hay, the height about four feet, and of proportionate length, for less than fifty shillings.

The truss is then encircled by the bands, at about 10 inches from each end, being afterwards turned under, as a tie, in the same manner as those of sheaves of corn. An expert hay-binder can thus truss two loads in his day's work; and the common price, if done by the job, is 2s. 6d. per load. It will be readily conceived that this mode is preferable to that of delivering hay loose; for although it occasions the charge of binding, it yet secures it from every kind of waste: it is accurately weighed, securely loaded upon the cart, occupies the smallest space, and can be easily carried or delivered, without difficulty, through a loft window.

Carriage

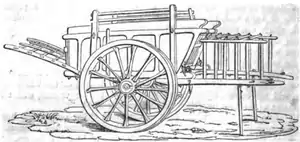

The London hay-cart may have been purpose-made to carry a load of 36 trusses. John French Burke wrote in 1834,[6]

...a more clumsy, ill-constructed vehicle cannot be imagined. With the occasional exception of a waggon, containing an additional half-load, it is the only vehicle used for the conveyance of hay and straw, and the return of dung, round the roads of the metropolis, and seems calculated to carry just a load, consisting of 18 cwt., divided into thirty-six trusses of hay, or the same number of straw, containing 36 lbs. each. The weight being light, and occupying a great deal of room, fills up the body of the cart, with the tail and fore ladders and iron arms; and the wheel-horse runs under head-rails. It requires very considerable exactitude in placing so bulky an article with regard to the centre of gravity; but the carters are so habituated to the load, that an accident but rarely occurs.

Consumption

British army regulations in 1799 specified standard rations of trusses. These were one truss of straw for each two soldiers, to stuff their palliasses. Half a truss was provided after sixteen days to refresh this and the whole was then changed after 32 days. Five trusses of straw were provided for each company every sixteen days for the batmen and washerwomen, who did not have palliasses. Thirty trusses of straw were provided per company when they took the field to thatch the huts of the washerwomen.[7]

References

- ↑ Rev. Dr. John Trusler (1790), The London Adviser and Guide, Wardour Street: Literary Press, p. 186

- ↑ "LXXXVIII An Act to Regulate the Buying and Selling of Hay and Straw", The Statutes, vol. 3, Eyre and Spottiswoode, 1872, pp. 428–438

- ↑ William Marriott (1801), The Country Gentlemen's Lawyer, Holborn: W. Stratford, pp. 71–80

- ↑ Cardarelli, François (2003), Encyclopaedia of Scientific Units, Weights and Measures, London: Springer, p. 49, ISBN 978-1-4471-1122-1

- ↑ John French Burke (1834), "ch. XXXII Haymaking", British Husbandry, vol. 1, Paternoster Row: Baldwin and Cradock, pp. 500–501

- ↑ John French Burke (1834), "ch. VII Cartage", British Husbandry, vol. 1, Paternoster Row: Baldwin and Cradock, pp. 163–164

- ↑ William Duane (1810), A Military Dictionary, Philadelphia, p. 660

_-_Trussing_Hay_-_WGA15689.jpg.webp)