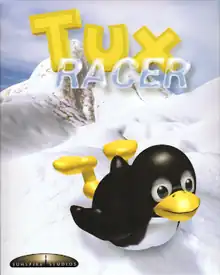

| Tux Racer | |

|---|---|

| |

| Developer(s) | Sunspire Studios |

| Publisher(s) | Sunspire Studios |

| Director(s) | Jasmin Patry |

| Composer(s) | George Sanger Joseph Toscano |

| Platform(s) | Linux, Windows, Mac |

| Release | Linux:

|

| Genre(s) | Racing |

| Mode(s) | Single-player |

Tux Racer is a 2000 open-source winter sports racing video game starring the Linux mascot, Tux the penguin. It was originally developed by Jasmin Patry as a computer graphics project at the University of Waterloo. Later on, Patry and the newly founded Sunspire Studios, composed of several former students of the university, expanded it. In the game, the player controls Tux as he slides down a course of snow and ice collecting herrings.

Tux Racer was officially downloaded over one million times as of 2001. It also was well received, often being acclaimed for the graphics, fast-paced gameplay, and replayability, and was a fan favorite among Linux users and the free software community. The game's popularity secured the development of a commercialized release that included enhanced graphics and multiplayer, and it also became the first GPL-licensed game to receive an arcade adaptation. It is the only product that Sunspire Studios developed and released, after which the company liquidated.

Gameplay

Tux Racer is a racing game in which the player must control Tux across a mountainside. Tux can turn left, right, brake, jump, and paddle, and flap his wings. If the player presses the brakes and turn buttons, Tux will perform a tight turn. Pressing the paddling buttons on the ground gives Tux some additional speed. The paddling stops giving speed and in turn slows Tux down when the speedometer turns yellow. Tux can slide off slopes or charge his jumps to temporarily launch into midair, during which he can flap his flippers to fly farther and adjust his direction left or right. The player can also reset the penguin should he be stuck in any part of the course.[1]

Courses are composed of various terrain types that affect Tux's performance. Sliding on ice allows speeding at the expense of traction, and snow allows for more maneuverability. However, rocky patches slow him down,[2]: 193 as does crashing into trees.[3] The player gains points by collecting herrings scattered along the courses, and the faster the player finishes the course, the higher the score. Players can select cups, where progression is by completing a series of courses in order by satisfying up to three requirements: collecting sufficient herring, finishing the course below a specified time, and scoring enough points. Failing to meet all the criteria or aborting the race costs a life, and should the player lose all four lives, they must reenter the cup and start over. During level selection, the player can choose daytime settings and weather conditions such as wind and fog that affect the gameplay.[1] Maps are composed of three separately saved raster layers that each determine a map's elevation, terrain layout,[3] and object placement.[4]

Commercial version

The commercial version of Tux Racer introduces new content. Besides Tux, players can select one of three other characters to race as: Samuel the seal, Boris the polar bear, and Neva the penguin.[5]: 6 Some courses contain jump and speed pads as power-ups, and players can perform tricks in midair to receive points.[5]: 4 They can participate in cups in one of the two events serving as game modes: the traditional "Solo Challenge" or the new "Race vs Opponents", where a computer opponent is added and must be defeated in order for the player to advance.[5]: 7 Courses are unlocked for completing unfinished cups. In non-campaign sessions, besides practicing,[5]: 9 players can also race in the two-player "Head to Head" local multiplayer mode, viewed on a split-screen.[5]: 10

Development

Tux Racer was originally developed by Jasmin Patry, a student attending the University of Waterloo in Ontario, Canada, where he aimed to begin a career in the video game industry by pursuing a computer graphics degree.[6] Development of the game began in August 1999 as a final computer graphics project in Computer Graphics Lab, and was completed in three days to positive class reception.[6][7] A webpage for the game was then started, and someone suggested he release the game's source code.[6]

Patry felt that made sense due to Tux being the mascot for the open-source Linux, and continued to work on the game before publicly uploading it to SourceForge for Linux under the free GNU General Public License on February 28, 2000, hoping others would join in on developing it.[3][6][8] This early version featured a very basic gameplay that consisted of Tux sliding down a hill of snow, ice, rock, and trees for Tux to avoid along the way. To write the game, Patry tended to use free premade content such as textures borrowed from websites, rather than original content made from scratch.[3]

In December 1999, Patry, fine arts students Rick Knowles and Mark Riddell, and computer graphics students Patrick Gilhuly, Eric Hall, and Rob Kroeger announced the foundation of the company Sunspire Studios to develop a video game project.[6] Patry stated the game would have a massively multiplayer and a persistent universe with real-time strategy and first-person shooter components. Since their ideas were limited by that time's 3D engines, they embarked on creating their own, which according to Patry would make Quake 3 and Unreal engine look "tame" in comparison. Fine arts undergraduate classmate Roger Fernandez was chosen as the artist. The project was eventually abandoned due to it being a "massive undertaking,"[6] and in August 2000, Knowles suggested the company resume working on Tux Racer, which became their first official project.[6] Continued development of the free version was swift; numerous elements such as herrings, jumping, and a soundtrack, as well as graphical improvements, were added in just three weeks. Porting the game from Linux to Windows was easy, as it used cross-platform tools such as OpenGL and Simple DirectMedia Layer.[6] A major update including those improvements, version 0.60, was freely uploaded to SourceForge for both Linux and Windows on October 2, 2000.[9] A minor patch for that release was often included in most Linux distributions,[2]: 191 and a port for Macintosh was released in November 21, 2000.[10]

Ports and remakes

On February 5, 2002, Sunspire Studios released in retail a closed-source and commercial expansion of the game titled Tux Racer, with each CD designed to support both Linux and Windows operating systems.[12][13] Improvements from the open-source version include a vastly enhanced engine and graphics, the ability to perform tricks, character selection, and competitive multiplayer.[14] The open-source version of Tux Racer, however, remained available to download on SourceForge.[2]: 191 Sunspire Studios ceased business towards the end of 2004.[12]

Since its inception, Tux Racer has seen unofficial updates.[15] One of the most popular examples is Extreme Tux Racer, released in September 2000, PlanetPenguin Racer.[16][17] An arcade version of the game was released by Roxor Games,[18] making it the first GPL-licensed video game to receive an arcade adaption.[11]

Reception

Tux Racer was well-received, with the latest version seeing over one million downloads as of October 2001 since its release in January, according to Sunspire Studios.[10][11] It was a favorite among Linux users, who often ranked it as the best or one of the best free games.[19][20][21][22][23][24][25] In August 2000, Lee Anderson of LinuxWorld.com commended the game's graphics, speed, and the easiness of the ability to create tracks.[3] In 2001, TuxRadar said the game provided a "shining light" of what free applications could achieve.[26] In its 2001 preview, the Brazilian magazine SuperGamePower considered the game's graphics to be the best aspect and described the sound as not innovative, but good.[27] Also in 2001, MacAddict compared the game's fast-paced style to podracing in Star Wars and summed up the Macintosh port as "more fun than words can describe."[28]

The commercial version of Tux Racer attracted little attention. Andon Logvinov of Igromania described it as a "pure arcade game" featuring nothing but four selectable characters and a set of courses with fish scattered about. He described the gameplay as calm and addictive and the music as relaxing, and praised the character models and track layout, with his only criticism being the system requirements.[29] Seiji Nakamura of the Japanese website Game Watch described it as cute and humorous and praised the game's graphics and shadow and reflection effects, but found the game to lack appeal for adults.[30]

Even after its production's cessation, Tux Racer has continued to be generally well-received. Linux Journal gave it an Editors' Choice Award in the "Game or Entertainment Software" category in 2005.[11] Digit applauded the graphics and replayability, as well as the speed of the game and the abundance of courses, but found the music to be monotonous.[31] Daniel Voicu of Softpedia praised the Extreme Tux Racer for being relaxing and funny and having the ability to reset Tux, as well as noted the game's fast pace, but criticized its perceived lack of interactivity and having Tux look like a "plastic puppet."[32] Linux For You called it entertaining but also criticized its bugs and the "plastic" look of Tux.[33]

See also

- SuperTuxKart, another racing video game featuring Tux and friends

References

- 1 2 3 "Manual". SourceForge. Sunspire Studios. Archived from the original on May 27, 2018. Retrieved July 4, 2019.

- 1 2 3 Dalheimer, Matthias Kalle; Welsh, Matt. Running Linux (5th ed.). O'Reilly Media. pp. 190–193.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Anderson, Lee. "Game review – TuxRacer". LinuxWorld.com. Archived from the original on October 18, 2000. Retrieved August 8, 2016.

- ↑ "Tux Racer FAQ". SourceForge. Sunspire Studios. Archived from the original on June 2, 2018. Retrieved July 4, 2019.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Tux Racer commercial manual. Sunspire Studios. February 2002. Retrieved July 12, 2019.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Ganthan, Durshan (November 3, 2000). "An equation for success - Waterloo grads create fun-filled game for all". Imprint. Archived from the original on January 27, 2001. Retrieved March 23, 2010.

- ↑ "University of Waterloo CS488/688 1998-1999 Gallery". University of Waterloo. March 9, 2000. Archived from the original on June 19, 2010. Retrieved March 22, 2010.

- ↑ "tuxracer / 0.10". SourceForge. Jasmin Patry. Archived from the original on July 27, 2019. Retrieved July 26, 2019.

- ↑ Hinuma, Satoshi (October 5, 2000). "ペンギンが雪山を滑り降りるスピード感満点の3Dゲーム「Tux Racer」v0.60". Windows Forest (in Japanese). Archived from the original on July 8, 2019. Retrieved July 7, 2019.

- 1 2 "Tux Racer news". Sunspire Studios. Archived from the original on June 18, 2019. Retrieved July 6, 2019.

- 1 2 3 4 Marti, Don (August 2005). "Editors' Choice Awards 2005". Linux Journal. No. 136. p. 86.

- 1 2 "Tux Racer website". Sunspire Studios. Archived from the original on September 4, 2004.

- ↑ "Tux Racer: Racing Penguins". GameStar (in German). January 18, 2002. Archived from the original on July 9, 2019. Retrieved July 9, 2019.

- ↑ "Tux Racer game info". Tux Racer website. Sunspire Studios. Archived from the original on February 3, 2004.

- ↑ Jackson, Jerry; O'Brien, Kevin; Baxter, Andrew (October 25, 2007). "Asus Eee PC Initial Hands On and Video Review". Notebook Review. Archived from the original on November 21, 2010. Retrieved March 29, 2010.

- ↑ Elrod, Corvus (September 27, 2007). "Extreme Tux Racer Released". The Escapist. Defy Media. Archived from the original on August 20, 2016. Retrieved August 10, 2016.

- ↑ Saunders, Mike (October 2014). "FOSSpicks". Linux Voice. No. 7. p. 73.

- ↑ LeClaire, Jennifer (July 31, 2005). "Stepping out". Austin Business Journal. Archived from the original on November 14, 2016. Retrieved July 6, 2019.

- ↑ Anderson, Lee (December 20, 2000). "Top 10 Linux games for the holidays". CNN. IDG. Archived from the original on August 29, 2004. Retrieved July 13, 2019.

- ↑ Hoffman, Tony (February 20, 2007). "Best Free Software—2007". PC Magazine. Vol. 26, no. 4. p. 71. Retrieved August 13, 2016.

- ↑ Heather Mead (November 1, 2004). "2004 Readers' Choice Awards". Linux Journal. Belltown Media, Inc. Archived from the original on February 11, 2012. Retrieved September 1, 2007.

- ↑ Heather Mead (November 1, 2003). "2003 Readers' Choice Awards". Linux Journal. Belltown Media, Inc. Archived from the original on May 12, 2013. Retrieved April 1, 2008.

- ↑ James Gray (May 1, 2008). "2008 Readers' Choice Awards". Linux Journal. Belltown Media, Inc. Archived from the original on May 9, 2013. Retrieved May 10, 2008.

- ↑ James Gray (May 1, 2009). "2009 Readers' Choice Awards". Linux Journal. Belltown Media, Inc. Archived from the original on May 4, 2009. Retrieved May 8, 2009.

- ↑ Gray, James (September 2005). "2005 Tux Readers' Choice Awards". Tux. No. 6. p. 27.

- ↑ "From the archives: the best games of 2001". TuxRadar. Future plc. April 9, 2009. Archived from the original on January 14, 2017. Retrieved August 6, 2016.

- ↑ "PC/Arcade Preview". SuperGamePower (in Portuguese). No. 82. January 2001. p. 46.

- ↑ "Indoor Fun for the Summer!". MacAddict. No. 59. July 2001. p. 8.

- ↑ Loginov, Andon (June 5, 2002). "Brief reviews. Tux Racer". Igromania (in Russian). Archived from the original on August 4, 2019. Retrieved August 3, 2019.

- ↑ Nakamura, Seiji (February 6, 2002). "本日到着! DEMO & PATCH". Game Watch (in Japanese). Archived from the original on August 6, 2017. Retrieved August 3, 2019.

- ↑ "Gaming Resources – Tux Racer". Digit. December 2005. pp. 107–108.

- ↑ Voicu, Daniel (May 15, 2008). "Extreme Tux Racer Review". Softpedia. Archived from the original on October 13, 2016. Retrieved August 6, 2016.

- ↑ Pal, Sayantan (September 2009). "Review – Extreme Tux Racer". Linux For You. Vol. 7, no. 7. p. 24.