| "The Twelve Days of Christmas" | |

|---|---|

| |

| Song | |

| Published | c. 1780 |

| Genre | Christmas carol |

| Composer(s) | Traditional with additions by Frederic Austin |

"The Twelve Days of Christmas" is an English Christmas carol. A classic example of a cumulative song, the lyrics detail a series of increasingly numerous gifts given to the speaker by their "true love" on each of the twelve days of Christmas (the twelve days that make up the Christmas season, starting with Christmas Day).[1][2] The carol, whose words were first published in England in the late eighteenth century, has a Roud Folk Song Index number of 68. A large number of different melodies have been associated with the song, of which the best known is derived from a 1909 arrangement of a traditional folk melody by English composer Frederic Austin.

Lyrics

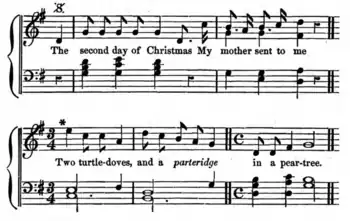

"The Twelve Days of Christmas" is a cumulative song, meaning that each verse is built on top of the previous verses. There are twelve verses, each describing a gift given by "my true love" on one of the twelve days of Christmas. There are many variations in the lyrics. The lyrics given here are from Frederic Austin's 1909 publication that established the current form of the carol.[3] The first three verses run, in full, as follows:

On the first day of Christmas my true love sent to me

A partridge in a pear tree

On the second day of Christmas my true love sent to me

Two turtle doves,

And a partridge in a pear tree.

On the third day of Christmas my true love sent to me

Three French hens,

Two turtle doves,

And a partridge in a pear tree.

Subsequent verses follow the same pattern. Each verse deals with the next day of Christmastide, adding one new gift and then repeating all the earlier gifts, so that each verse is one line longer than its predecessor.

- four calling birds

- five gold rings

- six geese a-laying

- seven swans a-swimming

- eight maids a-milking

- nine ladies dancing

- ten lords a-leaping

- eleven pipers piping

- twelve drummers drumming

Variations of the lyrics

The earliest known publications of the words to The Twelve Days of Christmas were an illustrated children's book, Mirth Without Mischief, published in London in 1780, and a broadsheet by Angus, of Newcastle, dated to the late eighteenth or early nineteenth centuries.[4][5]

While the words as published in Mirth without Mischief and the Angus broadsheet were almost identical, subsequent versions (beginning with James Orchard Halliwell's Nursery Rhymes of England of 1842) have displayed considerable variation:[6]

- In the earliest versions, the word on is not present at the beginning of each verse—for example, the first verse begins simply "The first day of Christmas". On was added in Austin's 1909 version, and became very popular thereafter.

- In the early versions "my true love sent to me" the gifts. However, a 20th-century variant has "my true love gave to me"; this wording has become particularly common in North America.[7]

- In one 19th-century variant, the gifts come from "my mother" rather than "my true love".

- Some variants have "juniper tree" or "June apple tree" rather than "pear tree", presumably a mishearing of "partridge in a pear tree".

- The 1780 version has "four colly birds"—colly being a regional English expression for "coal-black" (the name of the collie dog breed may come from this word).[8][9] This wording must have been opaque to many even in the 19th century: "canary birds", "colour'd birds", "curley birds", and "corley birds" are found in its place. Austin's 1909 version, which introduced the now-standard melody, also altered the fourth day's gift to four "calling" birds, and this variant has become the most popular, although "colly" is still found.

- "Five gold rings" has often become "five golden rings", especially in North America since the 1961 recording by Mitch Miller and The Gang.[7] In the standard melody, this change enables singers to fit one syllable per musical note.[10]

- The gifts associated with the final four days are often reordered. For example, the pipers may be on the ninth day rather than the eleventh.[9]

For ease of comparison with Austin's 1909 version given above:

(a) differences in wording, ignoring capitalisation and punctuation, are indicated in italics (including permutations, where for example the 10th day of Austin's version becomes the 9th day here);

(b) items that do not appear at all in Austin's version are indicated in bold italics.

| Source | Giver | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mirth without Mischief, 1780[4] |

My true love sent to me | Partridge in a pear-tree | Turtle doves | French hens | Colly birds | Gold rings | Geese a laying | Swans a swimming | Maids a milking | Drummers drumming | Pipers piping | Ladies dancing | Lords a leaping |

| Angus, 1774–1825[5] | My true love sent to me | Partridge in a pear tree | Turtle doves | French hens | Colly birds | Gold rings | Geese a laying | Swans a swimming | Maids a milking | Drummers drumming | Pipers piping | Ladies dancing | Lords a leaping |

| Baring-Gould, c. 1840 (1974)[11] | My true love sent to me | Part of a juniper tree | Turtle doves | French hens | Colley birds | A golden ring | Geese a laying | Swans a swimming | Hares a running | Ladies dancing | Lords a playing | Bears a baiting | Bulls a roaring |

| Halliwell, 1842[6] | My mother sent to me | Partridge in a pear-tree | Turtle doves | French hens | Canary birds | Gold rings | Geese a laying | Swans a swimming | Ladies dancing | Lords a leaping | Ships a sailing | Ladies spinning | Bells ringing |

| Rimbault, 1846[12] | My mother sent to me | Parteridge in a pear tree | Turtle doves | French hens | Canary birds | Gold rings | Geese a laying | Swans a swimming | Ladies dancing | Lords a leaping | Ships a sailing | Ladies spinning | Bells ringing |

| Halliwell, 1853[13] | My true love sent to me | Partridge in a pear tree | Turtle doves | French hens | Colly birds | Gold rings | Geese a laying | Swans a swimming | Maids a milking | Drummers drumming | Pipers piping | Ladies dancing | Lords a leaping |

| Salmon, 1855[14] | My true love sent to me | Partridge upon a pear-tree | Turtle-doves | French hens | Collie birds | Gold rings | Geese a-laying | Swans a-swimming | Maids a-milking | Drummers drumming | Pipers piping | Ladies dancing | Lords a-leaping |

| Caledonian, 1858[15] | My true love sent to me | Partridge upon a pear-tree | Turtle-doves | French hens | Collie birds | Gold rings | Geese a-laying | Swans a-swimming | Maids a-milking | Drummers drumming | Fifers fifing | Ladies dancing | Lords a-leaping |

| Husk, 1864[16] | My true love sent to me | Partridge in a pear-tree | Turtle doves | French hens | Colley birds | Gold rings | Geese a-laying | Swans a-swimming | Maids a-milking | Drummers drumming | Pipers piping | Ladies dancing | Lords a-leaping |

| Hughes, 1864[17] | My true love sent to me | Partridge and a pear tree | Turtle-doves | Fat hens | Ducks quacking | Hares running | "and so on" | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Cliftonian, 1867[18] | My true-love sent to me | Partridge in a pear-tree | Turtle-doves | French hens | Colley birds | Gold rings | Ducks a-laying | Swans swimming | Hares a-running | Ladies dancing | Lords a-leaping | Badgers baiting | Bells a-ringing |

| Clark, 1875[19] | My true love sent to me | Partridge in a pear tree | Turtle doves | French hens | Colour'd birds | Gold rings | Geese laying | Swans swimming | Maids milking | Drummers drumming | Pipers piping | Ladies dancing | Lords leaping |

| Kittredge, 1877 (1917)[20] | My true love sent to me | Some part of a juniper tree/And some part of a juniper tree | French hens | Turtle doves | Colly birds | Gold rings | Geese a-laying | Swans a-swimming | [forgotten by the singer] | Lambs a-bleating | Ladies dancing | Lords a-leading | Bells a-ringing |

| Henderson, 1879[21] | My true love sent to me | Partridge upon a pear tree | Turtle doves | French hens | Curley birds | Gold rings | Geese laying | Swans swimming | Maids milking | Drummers drumming | Pipers piping | — | — |

| Barnes, 1882[22] | My true love sent to me | The sprig of a juniper tree | Turtle doves | French hens | Coloured birds | Gold rings | Geese a-laying | Swans a-swimming | Hares a-running | Bulls a-roaring | Men a-mowing | Dancers a-dancing | Fiddlers a-fiddling |

| Stokoe, 1882[23] | My true love sent to me | Partridge on a pear tree | Turtle doves | French hens | Colly birds | Gold rings | Geese a-laying | Swans a-swimming | Maids a-milking | Drummers drumming | Pipers piping | Ladies dancing | Lords a leaping |

| Kidson, 1891[24] | My true love sent to me | Merry partridge on a pear tree | Turtle doves | French hens | Colley birds | Gold rings | Geese a-laying | Swans a-swimming | Maids a-milking | Drummers drumming | Pipers piping | Ladies dancing | Lords a leaping |

| Scott, 1892[25] | My true love brought to me | Very pretty peacock upon a pear tree | Turtle-doves | French hens | Corley birds | Gold rings | Geese a-laying | Swans a-swimming | Maids a-milking | Pipers playing | Drummers drumming | Lads a-louping | Ladies dancing |

| Cole, 1900[26] | My true love sent to me | Parteridge upon a pear tree | Turtle doves | French hens | Colly birds | Gold rings | Geese a laying | Squabs a swimming | Hounds a running | Bears a beating | Cocks a crowing | Lords a leaping | Ladies a dancing |

| Sharp, 1905[27] | My true love sent to me | Goldie ring, and the part of a June apple tree | Turtle doves, and the part of a mistletoe bough | French hens | Colley birds | Goldie rings | Geese a-laying | Swans a-swimming | Boys a-singing | Ladies dancing | Asses racing | Bulls a-beating | Bells a-ringing |

| Leicester Daily Post, 1907[28] | My true love sent to me | A partridge upon a pear-tree | Turtle doves | French hens | Collie dogs | Gold rings | Geese a-laying | Swans a-swimming | Maids a milking | Drummers drumming | Pipers playing | Ladies dancing | Lords a-leaping |

| Austin, 1909[3] | My true love sent to me | Partridge in a pear tree | Turtle doves | French hens | Calling birds | Gold rings | Geese a-laying | Swans a-swimming | Maids a-milking | Ladies dancing | Lords a-leaping | Pipers piping | Drummers drumming |

| Swortzell, 1966[7] | My true love gave to me | Partridge in a pear tree | Turtle doves | French hens | Collie birds | Golden rings | Geese a-laying | Swans a-swimming | Maids a-milking | Pipers piping | Drummers drumming | Lords a-leaping | Ladies dancing |

Scotland

A similar cumulative verse from Scotland, "The Yule Days", has been likened to "The Twelve Days of Christmas" in the scholarly literature.[20] It has thirteen days rather than twelve, and the number of gifts does not increase in the manner of "The Twelve Days". Its final verse, as published in Chambers, Popular Rhymes, Fireside Stories, and Amusements of Scotland (1842), runs as follows:[29]

The king sent his lady on the thirteenth Yule day,

Three stalks o' merry corn,

Three maids a-merry dancing,

Three hinds a-merry hunting,

An Arabian baboon,

Three swans a-merry swimming,

Three ducks a-merry laying,

A bull that was brown,

Three goldspinks,

Three starlings,

A goose that was grey,

Three plovers,

Three partridges,

A pippin go aye;

Wha learns my carol and carries it away?

"Pippin go aye" (also spelled "papingo-aye" in later editions) is a Scots word for peacock[30] or parrot.[31]

Similarly, Iceland has a Christmas tradition where "Yule Lads" put gifts in the shoes of children for each of the 13 nights of Christmas.

Faroe Islands

In the Faroe Islands, there is a comparable counting Christmas song. The gifts include: one feather, two geese, three sides of meat, four sheep, five cows, six oxen, seven dishes, eight ponies, nine banners, ten barrels, eleven goats, twelve men, thirteen hides, fourteen rounds of cheese and fifteen deer.[32] These were illustrated in 1994 by local cartoonist Óli Petersen (born 1936) on a series of two stamps issued by the Faroese Philatelic Office.[33]

Sweden

In Blekinge and Småland, southern Sweden, a similar song was also sung. It featured one hen, two barley seeds, three grey geese, four pounds of pork, six flayed sheep, a sow with six pigs, seven åtting grain, eight grey foals with golden saddles, nine newly born cows, ten pairs of oxen, eleven clocks, and finally twelve churches, each with twelve altars, each with twelve priests, each with twelve capes, each with twelve coin-purses, each with twelve daler inside.[34][35]

France

"Les Douze Mois" ("The Twelve Months") (also known as "La Perdriole"—"The Partridge")[36] is another similar cumulative verse from France that has been likened to The Twelve Days of Christmas.[20] Its final verse, as published in de Coussemaker, Chants Populaires des Flamands de France (1856), runs as follows:[37]

Le douzièm' jour d'l'année,

Que me donn'rez vous ma mie?

Douze coqs chantants,

Onze plats d'argent,

Dix pigeons blancs,

Neuf bœufs cornus,

Huit vaches mordants,

Sept moulins à vent,

Six chiens courants,

Cinq lapins courant par terre,

Quat' canards volant en l'air,

Trois rameaux de bois,

Deux tourterelles,

Un' perdrix sole,

Qui va, qui vient, qui vole,

Qui vole dans les bois.The twelfth day of the year

What will you give me, my love?

Twelve singing cockerels,

Eleven silver dishes,

Ten white pigeons,

Nine horned oxen,

Eight biting cows,

Seven windmills,

Six running dogs,

Five rabbits running along the ground,

Four ducks flying in the air,

Three wooden branches,

Two turtle doves,

One lone partridge,

Who goes, who comes, who flies,

Who flies in the woods.

According to de Coussemaker, the song was recorded "in the part of [French] Flanders that borders on the Pas de Calais".[37] Another similar folksong, "Les Dons de l'An", was recorded in the Cambresis region of France. Its final verse, as published in 1864, runs:[38][39]

Le douzièm' mois de l'an,

que donner à ma mie?

Douz' bons larrons,

Onze bons jambons,

Dix bons dindons,

Neuf bœufs cornus,

Huit moutons tondus,

Sept chiens courants,

Six lièvres aux champs,

Cinq lapins trottant par terre,

Quatre canards volant en l'air,

Trois ramiers de bois,

Deux tourterelles,

Une pertriolle,

Qui vole, et vole, et vole,

Une pertriolle,

Qui vole

Du bois au champ.The twelfth month of the year

What should I give my love?

Twelve good cheeses,[40]

Eleven good hams,

Ten good turkeycocks,

Nine horned oxen,

Eight sheared sheep,

Seven running dogs,

Six hares in the field,

Five rabbits trotting along the ground,

Four ducks flying in the air,

Three wood pigeons,

Two turtle doves,

One young partridge,[41]

Who flies, who flies, who flies,

One young partridge,

Who flies

From the wood to the field.

History and meaning

Origins

The exact origins and the meaning of the song are unknown, but it is highly probable that it originated from a children's memory and forfeit game.[42]

The twelve days in the song are the twelve days starting with Christmas Day to the day before Epiphany (6 January). Twelfth Night is defined by the Oxford English Dictionary as "the evening of January 5th, the day before Epiphany, which traditionally marks the end of Christmas celebrations".[43]

The best known English version was first printed in Mirth without Mischief, a children's book published in London around 1780. The work was heavily illustrated with woodcuts, attributed in one source to Thomas Bewick.[44]

In the northern counties of England, the song was often called the "Ten Days of Christmas", as there were only ten gifts. It was also known in Somerset, Dorset, and elsewhere in England. The kinds of gifts vary in a number of the versions, some of them becoming alliterative tongue-twisters.[45] "The Twelve Days of Christmas" was also widely popular in the United States and Canada. It is mentioned in the section on "Chain Songs" in Stith Thompson's Motif-Index of Folk-Literature (Indiana University Studies, Vol. 5, 1935), p. 416.

There is evidence pointing to the North of England, specifically the area around Newcastle upon Tyne, as the origin of the carol. Husk, in the 1864 excerpt quoted below, stated that the carol was "found on broadsides printed at Newcastle at various periods during the last hundred and fifty years", i.e. from approximately 1714. In addition, many of the nineteenth century citations come from the Newcastle area.[14][21][23][25] Peter and Iona Opie suggest that "if '[t]he partridge in the peartree' is to be taken literally it looks as if the chant comes from France, since the Red Leg partridge, which perches in trees more frequently than the common partridge, was not successfully introduced into England until about 1770".[46]

Some authors suggest a connection to a religious verse entitled "Twelfth Day", found in a thirteenth century manuscript at Trinity College, Cambridge;[47][48][49] this theory is criticised as "erroneous" by Yoffie.[50] It has also been suggested that this carol is connected to the "old ballad" which Sir Toby Belch begins to sing in Shakespeare's Twelfth Night.[51]

Manner of performance

Many early sources suggest that The Twelve Days of Christmas was a "memory-and-forfeits" game, in which participants were required to repeat a verse of poetry recited by the leader. Players who made an error were required to pay a penalty, in the form of offering a kiss or confection.[52]

Halliwell, writing in 1842, stated that "[e]ach child in succession repeats the gifts of the day, and forfeits for each mistake."[6]

Salmon, writing from Newcastle, claimed in 1855 that the song "[had] been, up to within twenty years, extremely popular as a schoolboy's Christmas chant".[14]

Husk, writing in 1864, stated:[53]

This piece is found on broadsides printed at Newcastle at various periods during the last hundred and fifty years. On one of these sheets, nearly a century old, it is entitled "An Old English Carol," but it can scarcely be said to fall within that description of composition, being rather fitted for use in playing the game of "Forfeits," to which purpose it was commonly applied in the metropolis upwards of forty years since. The practice was for one person in the company to recite the first three lines; a second, the four following; and so on; the person who failed in repeating her portion correctly being subjected to some trifling forfeit.

Thomas Hughes, in a short story published in 1864, described a fictional game of Forfeits involving the song:[17]

[A] cry for forfeits arose. So the party sat down round Mabel on benches brought out from under the table, and Mabel began, --

The first day of Christmas my true love sent to me a partridge and a pear-tree;

The second day of Christmas my true love sent to me two turtle-doves, a partridge, and a pear-tree;

The third day of Christmas my true love sent to me three fat hens, two turtle-doves, a partridge, and a pear-tree;

The fourth day of Christmas my true love sent to me four ducks quacking, three fat hens, two turtle-doves, a partridge, and a pear-tree;

The fifth day of Christmas my true love sent to me five hares running, four ducks quacking, three fat hens, two turtle-doves, a partridge, and a pear-tree;

And so on. Each day was taken up and repeated all round; and for every breakdown (except by little Maggie, who struggled with desperately earnest round eyes to follow the rest correctly, but with very comical results), the player who made the slip was duly noted down by Mabel for a forfeit.

Barnes (1882), stated that the last verse "is to be said in one breath".[22]

Scott (1892), reminiscing about Christmas and New Year's celebrations in Newcastle around the year 1844, described a performance thus:[25]

A lady begins it, generally an elderly lady, singing the first line in a high clear voice, the person sitting next takes up the second, the third follows, at first gently, but before twelfth day is reached the whole circle were joining in with stentorian noise and wonderful enjoyment.

Lady Gomme wrote in 1898:[54]

"The Twelve Days" was a Christmas game. It was a customary thing in a friend's house to play "The Twelve Days," or "My Lady's Lap Dog," every Twelfth Day night. The party was usually a mixed gathering of juveniles and adults, mostly relatives, and before supper—that is, before eating mince pies and twelfth cake—this game and the cushion dance were played, and the forfeits consequent upon them always cried. The company were all seated round the room. The leader of the game commenced by saying the first line. [...] The lines for the "first day" of Christmas was said by each of the company in turn; then the first "day" was repeated, with the addition of the "second" by the leader, and then this was said all round the circle in turn. This was continued until the lines for the "twelve days" were said by every player. For every mistake a forfeit—a small article belonging to the person—had to be given up. These forfeits were afterwards "cried" in the usual way, and were not returned to the owner until they had been redeemed by the penalty inflicted being performed.

Meanings of the gifts

Partridge in a pear tree

An anonymous "antiquarian", writing in 1867, speculated that "pear-tree" is a corruption of French perdrix ([pɛʁ.dʁi], "partridge").[18] This was also suggested by Anne Gilchrist, who observed in 1916 that "from the constancy in English, French, and Languedoc versions of the 'merry little partridge,' I suspect that 'pear-tree' is really perdrix (Old French pertriz) carried into England".[55] The variant text "part of a juniper tree", found as early as c. 1840, is likely not original, since "partridge" is found in the French versions.[11][48] It is probably a corruption of "partridge in a pear tree", though Gilchrist suggests "juniper tree" could have been joli perdrix, [pretty partridge].[56][55]

Another suggestion is that an old English drinking song may have furnished the idea for the first gift. William B. Sandys refers to it as a "convivial glee introduced a few years since, 'A Pie [i.e., a magpie] sat on a Pear Tree,' where one drinks while the others sing."[57] The image of the bird in the pear tree also appears in lines from a children's counting rhyme an old Mother Goose.[45]

- A pye sate on a pear tree, Heigh O

- Once so merrily hopp'd she; Heigh O

- Twice so merrily, etc.

- Thrice so, etc.

French hens

Gilchrist suggests that the adjective "French" may mean "foreign".[55] Sharp reports that one singer sings "Britten chains", which he interprets as a corruption of "Breton hens".[58] William and Ceil Baring-Gould also suggest that the birds are Breton hens, which they see as another indication that the carol is of French origin.[59]

Colly birds

The word "colly", found in the earliest publications, was the source of considerable confusion.[60] Multiple sources confirm that it is a dialectal word, found in Somerset and elsewhere, meaning "black", so "colly birds" are blackbirds.[14][55] Despite this, other theories about the word's origin are also found in the literature, such as that the word is a corruption of French collet ("ruff"), or of "coloured".[18][47]

Gold rings

Shahn suggests that "the five golden rings refer to the ringed pheasant".[61] William and Ceil Baring-Gould reiterate this idea, which implies that the gifts for first seven days are all birds.[59] Others suggest the gold rings refer to "five goldspinks"—a goldspink being an old name for a goldfinch;[62] or even canaries.[lower-alpha 1] However, the 1780 publication includes an illustration that clearly depicts the "five gold rings" as being jewellery.[4]

General

According to The Oxford Dictionary of Nursery Rhymes, "Suggestions have been made that the gifts have significance, as representing the food or sport for each month of the year. Importance [certainly has] long been attached to the Twelve Days, when, for instance, the weather on each day was carefully observed to see what it would be in the corresponding month of the coming year. Nevertheless, whatever the ultimate origin of the chant, it seems probable [that] the lines that survive today both in England and France are merely an irreligious travesty."[46] In 1979, a Canadian hymnologist, Hugh D. McKellar, published an article, "How to Decode the Twelve Days of Christmas", in which he suggested that "The Twelve Days of Christmas" lyrics were intended as a catechism song to help young English Catholics learn their faith, at a time when practising Catholicism was against the law (from 1558 until 1829).[64] McKellar offered no evidence for his claim. Three years later, in 1982, Fr. Hal Stockert wrote an article (subsequently posted online in 1995) in which he suggested a similar possible use of the twelve gifts as part of a catechism. The possibility that the twelve gifts were used as a catechism during the period of Catholic repression was also hypothesised in this same time period (1987 and 1992) by Fr. James Gilhooley, chaplain of Mount Saint Mary College of Newburgh, New York.[65][66] Snopes.com claims this to be false, but offers no facts or evidence, other than theory, to substantiate their claims.[67]

Music

Standard melody

The now-standard melody for the carol was popularised by the English baritone and composer Frederic Austin. The singer, having arranged the music for solo voice with piano accompaniment, included it in his concert repertoire from 1905 onwards.[68] A Times review from 1906 praised the "quaint folk-song", while noting that "the words ... are better known than the excellent if intricate tune".[69]

.png.webp)

Austin's arrangement was published by Novello & Co. in 1909.[70][71][72][73] According to a footnote added to the posthumous 1955 reprint of his musical setting, Austin wrote:[74]

This song was, in my childhood, current in my family. I have not met with the tune of it elsewhere, nor with the particular version of the words, and have, in this setting, recorded both to the best of my recollection. F. A.

A number of later publications state that Austin's music for "five gold rings" is an original addition to an otherwise traditional melody. An early appearance of this claim is found in the 1961 University Carol Book, which states:[75][76]

This is a traditional English singing game but the melody of five gold rings was added by Richard [sic] Austin whose fine setting (Novello) should be consulted for a fuller accompaniment.

Similar statements are found in John Rutter's 1967 arrangement,[77] and in the 1992 New Oxford Book of Carols.[78]

Many of the decisions Austin made with regard to the lyrics subsequently became widespread:

- The initial "On" at the beginning of each verse.

- The use of "calling birds", rather than "colly birds", on the fourth day.

- The ordering of the ninth to twelfth verses.

The time signature of this song is not constant, unlike most popular music. This irregular meter perhaps reflects the song's folk origin. The introductory lines "On the [nth] day of Christmas, my true love gave to me", are made up of two 4

4 bars, while most of the lines naming gifts receive one 3

4 bar per gift with the exception of "Five gold rings", which receives two 4

4 bars, "Two turtle doves" getting a 4

4 bar with "And a" on its fourth beat and "partridge in a pear tree" getting two 4

4 bars of music. In most versions, a 4

4 bar of music immediately follows "partridge in a pear tree". "On the" is found in that bar on the fourth (pickup) beat for the next verse. The successive bars of three for the gifts surrounded by bars of four give the song its hallmark "hurried" quality.

The second to fourth verses' melody is different from that of the fifth to twelfth verses. Before the fifth verse (when "Five gold rings" is first sung), the melody, using solfege, is "sol re mi fa re" for the fourth to second items, and this same melody is thereafter sung for the twelfth to sixth items. However, the melody for "four colly birds, three French hens, two turtle doves" changes from this point, differing from the way these lines were sung in the opening four verses.

In the final verse, Austin inserted a flourish on the words "Five gold rings". This has not been copied by later versions, which simply repeat the melody from the earlier verses.

Earlier melodies

The earliest known sources for the text, such as Mirth Without Mischief, do not include music.

A melody, possibly related to the "traditional" melody on which Austin based his arrangement, was recorded in Providence, Rhode Island in 1870 and published in 1905.[79] Cecil Sharp's Folk Songs from Somerset (1905) contains two different melodies for the song, both distinct from the now-standard melody.[27]

!["[C]opied from a manuscript of 1790"](../I/Twelve_Days_of_Christmas_(Barry_1790).png.webp) "[C]opied from a manuscript of 1790"[79]

"[C]opied from a manuscript of 1790"[79]!["[C]ollected by the late Mr. John Bell, of Gateshead, about eighty years ago" [i.e. around 1808] Playⓘ](../I/Twelve_Days_Stokoe.png.webp) "[C]ollected by the late Mr. John Bell, of Gateshead, about eighty years ago" [i.e. around 1808][23] ⓘ

"[C]ollected by the late Mr. John Bell, of Gateshead, about eighty years ago" [i.e. around 1808][23] ⓘ From Edward Rimbault's Nursery Rhymes, with the Tunes to which They Are Still Sung in the Nurseries of England (1846)[12]

From Edward Rimbault's Nursery Rhymes, with the Tunes to which They Are Still Sung in the Nurseries of England (1846)[12]!["[R]ecorded about 1875 by a lady of Providence, RI, from the singing of an aged man."](../I/Twelve_Days_of_Christmas_(Barry_1875).png.webp) "[R]ecorded about 1875 by a lady of Providence, RI, from the singing of an aged man."[79]

"[R]ecorded about 1875 by a lady of Providence, RI, from the singing of an aged man."[79].png.webp) Current in "country villages in Wiltshire", according to an 1891 newspaper article[24]

Current in "country villages in Wiltshire", according to an 1891 newspaper article[24]!["[A]s sung by the Allens at the Homestead, Castle Hill, Medfield, Massachusetts, 1899"](../I/Twelve_Days_of_Christmas_(Barry_1899).png.webp) "[A]s sung by the Allens at the Homestead, Castle Hill, Medfield, Massachusetts, 1899"[80]

"[A]s sung by the Allens at the Homestead, Castle Hill, Medfield, Massachusetts, 1899"[80]!["[S]ung by Mr. George Wyatt, at West Harptree, Somerset, April 15th, 1904".](../I/Twelve_Days_of_Christmas_(Wyatt_1904).png.webp) "[S]ung by Mr. George Wyatt, at West Harptree, Somerset, April 15th, 1904".[81]

"[S]ung by Mr. George Wyatt, at West Harptree, Somerset, April 15th, 1904".[81]

Several folklorists have recorded the carol using traditional melodies. Peter Kennedy recorded the Copper family of Sussex, England singing a version in 1955 which differs slightly from the common version,[82] whilst Helen Hartness Flanders recorded several different versions in the 1930s and 40s in New England,[83][84][85][86] where the song seems to have been particularly popular. Edith Fowke recorded a single version sung by Woody Lambe of Toronto, Canada in 1963,[87] whilst Herbert Halpert recorded one version sung by Oscar Hampton and Sabra Bare in Morgantown, North Carolina One interesting version was also recorded in 1962 in Deer, Arkansas, performed by Sara Stone;[88] the recording is available online courtesy of the University of Arkansas.[89]

Parodies and other versions

- Bing Crosby and the Andrews Sisters recorded the traditional version of this song on 10 May 1949 for Decca Records.[90]

- The Ray Conniff Singers recorded a traditional version in 1962, appearing on the album We Wish You a Merry Christmas.

- Jasper Carrott performed "Twelve Drinks of Christmas" where he appears to be more inebriated with each successive verse.[91] This was based on Scottish comedian Bill Barclay's version.[92]

- Perry Como recorded a traditional version of "Twelve Days of Christmas" for RCA Victor in 1953, but varied the lyrics with "11 Lords a Leaping", "10 Ladies Dancing", and "9 Pipers Piping". The orchestrations were done by Mitchell Ayres.

- Allan Sherman released two different versions of "The Twelve Gifts of Christmas".[93] Sherman wrote and performed his version of the classic Christmas carol on a 1963 TV special that was taped well in advance of the holiday. Warner Bros. Records rushed out a 45 RPM version in early December.[94]

- Alvin and the Chipmunks covered the song for their 1963 album Christmas with The Chipmunks, Vol. 2.

- The illustrator Hilary Knight included A Firefly in a Fir Tree in his Christmas Nutshell Library, a boxed set of four miniature holiday-themed books published in 1963.[95] In this rendition, the narrator is a mouse, with the various gifts reduced to mouse scale, such as "nine nuts for nibbling" and "four holly berries".[96] Later released separately with the subtitle A Carol for Mice.[96]

- Frank Sinatra and his children, Frank Sinatra Jr., Nancy Sinatra, and Tina Sinatra, included their own version of "The Twelve Days of Christmas" on their 1968 album, The Sinatra Family Wish You a Merry Christmas.[97]

- Sears put out a special Christmas coloring book with Disney's Winnie-the-Pooh characters in 1973 featuring a version of the carol focusing on Pooh's attempts to get a pot of honey from a hollow honey tree, with each verse ending in "and a hunny pot inna hollow tree".

- Fay McKay, an American musical comedian, is best known for "The Twelve Daze of Christmas", a parody in which the gifts were replaced with various alcoholic drinks, resulting in her performance becoming increasingly inebriated over the course of the song.[98]

- A radio play written by Brian Sibley, "And Yet Another Partridge in a Pear Tree" was broadcast on BBC Radio 4 on Christmas Day 1977.[99] Starring Penelope Keith, it imagines the increasingly exasperated response of the recipient of the "twelve days" gifts.[100] It was rebroadcast in 2011.[101]

- The Muppets and singer-songwriter John Denver performed "The Twelve Days of Christmas" on the 1979 television special John Denver and the Muppets: A Christmas Together. It was featured on the album of the same name. The song has been recorded by the Muppets five different times, featuring different Muppets in different roles each time.[102]

- A Māori / New Zealand version, titled "A Pukeko in a Ponga Tree", written by Kingi Matutaera Ihaka, appeared as a picture book and cassette recording in 1981.[103][104]

- On the late-night sketch-comedy program Second City TV in 1982, the Canadian-rustic characters Bob & Doug McKenzie (Rick Moranis and Dave Thomas) released a version on the SCTV spin-off album Great White North.[105]

- The Twelve Days of Christmas (TV 1993), an animated tale which aired on NBC, features the voices of Marcia Savella, Larry Kenney, Carter Cathcart, Donna Vivino and Phil Hartman.[106]

- VeggieTales parodied "The Twelve Days of Christmas" under the title "The 8 Polish Foods of Christmas" in the 1996 album A Very Veggie Christmas. It was later rerecorded as a Silly Song for the episode The Little Drummer Boy in 2011.[107]

- Christian rock band Relient K released a recording of the song on their 2007 album Let It Snow, Baby... Let It Reindeer. This version known for its slightly satirical refrain: "What's a partridge? What's a pear tree? I don't know, so please don't ask me. But I can bet those are terrible gifts to get."[108]

- A program hosted by Tom Arnold, The 12 Days of Redneck Christmas, which takes a look at Christmas traditions, premiered on CMT in 2008. The theme music is "The Twelve Days of Christmas".[109]

- Shannon Chan-Kent, as her character of Pinkie Pie from My Little Pony: Friendship Is Magic, sings her own version of the song on the album My Little Pony: It's a Pony Kind of Christmas.[110]

- Irish actor Frank Kelly recorded "Christmas Countdown" in 1982 in which a man named Gobnait O'Lúnasa receives the 12 Christmas gifts referenced in the song from a lady named Nuala. As each gift is received, Gobnait gets increasingly upset with the person who sent them, as said gifts wreak havoc in the house where he lives with his mother. This version charted in both Ireland (where it reached number 8 in 1982) and the UK (entering the UK chart in December 1983 and reaching number 26).[111][112] The song peaked at number 15 in Australia in 1984.[113]

- A special Creature Comforts orchestral arrangement of "The Twelve Days of Christmas" was made by British animator Nick Park and Aardman Animations. Featuring different animals discussing or trying to remember the lyrics of the song, it was released on Christmas Day 2005.[114]

- New Orleans band Benny Grunch and the Bunch perform a "locals-humor take" on the song, titled "The Twelve Yats of Christmas".[115][116]

- The video game StarCraft: Broodwar released a new map named Twelve Days of StarCraft with the song which was adopted a new lyric featured units from the game by Blizzard on 23 December 1999.[117] In 2013, CarbotAnimations created a new web animation, StarCraft's Christmas Special 2013 the Twelve Days of StarCrafts, with the song which was played in the map Twelve Days of Starcraft.[118]

- In Hawaii, The Twelve Days of Christmas, Hawaiian Style, with the words by Eaton Bob Magoon Jr., Edward Kenny, and Gordon N. Phelps, is popular. It is typically sung by children in concerts with proper gesticulation.[119][120]

- A version by Crayola was made in 2008 titled The 64 Days of Crayola.

- American rock and roll radio on-air personality Bob Rivers made a version of the song, The Twelve Pains of Christmas (from Twisted Christmas, 1988), replacing the traditional gifts with a list of hassles associated with Christmas, such as installing decorative lighting, or going shopping for gifts.

- In the 12 Disasters of Christmas movie, the song has actually been created by the Mayas to ensure that a prophecy of the end of the world be foretold among Europeans even after the destruction of the Mayas' civilization.

- With reference to President Trump’s impeachment just before Christmas 2019, the Washington International Chorus performed the 12 Days of Christmas carol, with specially adapted lyrics by BBC News.

Christmas Price Index

Since 1984, the cumulative costs of the items mentioned in the Frederic Austin version have been used as a tongue-in-cheek economic indicator. Assuming the gifts are repeated in full in each round of the song, then a total of 364 items are delivered by the twelfth day.[121][122] This custom began with and is maintained by PNC Bank.[123][124] Two pricing charts are created, referred to as the Christmas Price Index and The True Cost of Christmas. The former is an index of the current costs of one set of each of the gifts given by the True Love to the singer of the song "The Twelve Days of Christmas". The latter is the cumulative cost of all the gifts with the repetitions listed in the song. The people mentioned in the song are hired, not purchased. The total costs of all goods and services for the 2015 Christmas Price Index is US$34,130.99,[125] or $155,407.18 for all 364 items.[126][127] The original 1984 cost was $12,623.10. The index has been humorously criticised for not accurately reflecting the true cost of the gifts featured in the Christmas carol.[128]

John Julius Norwich's 1998 book, The Twelve Days of Christmas (Correspondence), uses the motif of repeating the previous gifts on each subsequent day, to humorous effect.

Computational complexity

In the famous article The Complexity of Songs, Donald Knuth computes the space complexity of the song as function of the number of days, observing that a hypothetical "The Days of Christmas" requires a memory space of as where is the length of the song, showing that songs with complexity lower than indeed exist. Incidentally, it is also observed that the total number of gifts after days equals .[129]

In 1988, a C program authored by Ian Philipps won the International Obfuscated C Code Contest. The code, which according to the jury of the contest "looked like what you would get by pounding on the keys of an old typewriter at random", takes advantage of the recursive structure of the song to print its lyrics with code that is shorter than the lyrics themselves.[130]

Notes

References

Footnotes

- ↑ Truscott, Jeffrey A. (2011). Worship. Armour Publishing. p. 103. ISBN 9789814305419.

As with the Easter cycle, churches today celebrate the Christmas cycle in different ways. Practically all Protestants observe Christmas itself, with services on 25 December or the evening before. Anglicans, Lutherans and other churches that use the ecumenical Revised Common Lectionary will likely observe the four Sundays of Advent, maintaining the ancient emphasis on the eschatological (First Sunday), ascetic (Second and Third Sundays), and scriptural/historical (Fourth Sunday). Besides Christmas Eve/Day, they will observe a 12-day season of Christmas from 25 December to 5 January.

- ↑ Scott, Brian (2015). But Do You Recall? 25 Days of Christmas Carols and the Stories Behind Them. p. 114.

Called Christmastide or Twelvetide, this twelve-day version began on December 25, Christmas Day, and lasted until the evening of January 5. During Twelvetide, other feast days are celebrated.

- 1 2 Austin (1909).

- 1 2 3 Anonymous (1780). Mirth without Mischief. London: Printed by J. Davenport, George's Court, for C. Sheppard, no. 8, Aylesbury Street, Clerkenwell. pp. 5–16.

- 1 2 The Twelve Days of Christmas. Newcastle: Angus – via Bodleian Library.

- 1 2 3 Halliwell, James Orchard (1842). The Nursery Rhymes of England. Percy Society. Early English poetry, v. IV. London: Percy Society. pp. 127–128. hdl:2027/iau.31858030563740.

- 1 2 3 For example, Swortzell, Lowell (1966). A Partridge in a Pear Tree: A Comedy in One Act. New York: Samuel French. p. 20. ISBN 0-573-66311-4.

- ↑ http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/colly, http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/collie

- 1 2 "The Twelve Days of Christmas". Active Bible Church of God, Chicago (Hyde Park), Illinois. Archived from the original on 17 August 2012. Retrieved 16 December 2014. Annotations reprinted from 4000 Years of Christmas by Earl W. Count (New York: Henry Schuman, 1948)

- ↑ "Gold keeps the 'Twelve Days of Christmas' cost a-leaping". Pittsburgh Tribune-Review. Retrieved 8 December 2009.

- 1 2 In a manuscript by Cecily Baring-Gould, dated "about 1840", transcribed in Baring-Gould, Sabine (1974). Hitchcock, Gordon (ed.). Folk Songs of the West Country. Newton Abbot, Devon: David & Charales. pp. 102–103. ISBN 0715364197.; note that the linked webpage misidentifies the book in which this melody was published.

- 1 2 Rimbault, Edward F. (n.d.). Nursery Rhymes, with the Tunes to Which They Are Still Sung in the Nurseries of England. London: Cramer, Beale & Co. pp. 52–53. hdl:2027/wu.89101217990.. Undated; date of 1846 confirmed by this catalogue from the Bodleian Library (p. 112), and an advertisement in the Morning Herald ("Christmas Carols". Morning Herald: 8. 25 December 1846.).

- ↑ Halliwell, James Orchard (1853). The Nursery Rhymes and Nursery Tales of England (Fifth ed.). London: Frederick Warne and Co. pp. 73–74. hdl:2027/uc1.31175013944015.

- 1 2 3 4 Salmon, Robert S. (29 December 1855). "Christmas Jingle". Notes and Queries. London: George Bell. xii: 506–507. hdl:2027/nyp.33433081666293.

- ↑ "Christmas Carol". The Caledonian. St. Johnsbury, VT. 22 (25): 1. 25 December 1858.

- ↑ Husk (1864), pp. 181–185.

- 1 2 Thomas Hughes, "The Ashen Fagot", in Household Friends for Every Season. Boston, MA: Ticknor and Fields. 1864. p. 34.

- 1 2 3 An Antiquarian (December 1867). "Christmas Carols". The Cliftonian. Clifton, Bristol: J. Baker: 145–146.

- ↑ Clark, Georgiana C. (c. 1875). Jolly Games for Happy Homes. London: Dean & Son. pp. 238–242.

- 1 2 3 Kittredge, G. L., ed. (July–September 1917). "Ballads and Songs". The Journal of American Folk-Lore. Lancaster, PA: American Folk-Lore Society. XXX (CXVII): 365–367.

Taken down by G. L. Kittredge, Dec. 30, 1877, from the singing of Mrs Sarah G. Lewis of Barnstaple, Mass. (born in Boston, 1799). Mrs. Lewis learned the song when a young girl from her grandmother, Mrs. Sarah Gorham.

- 1 2 Henderson, William (1879). Notes on the Folk-lore of the Northern Counties of England and the Borders. London: Satchell, Peyton and Co. p. 71.

- 1 2 Barnes, W. (9 February 1882). "Dorset Folk-lore and Antiquities". Dorset County Chronicle and Somersetshire Gazette: 15.

- 1 2 3 Bruce, J. Collingwood; Stokoe, John (1882). Northumbrian Ministrelsy. Society of Antiquaries of Newcastle-upon-Tyne. pp. 129–131. hdl:2027/uc1.c034406758.. Reprinted at Stokoe, John (January 1888). "The North-Country Garland of Song". The Monthly Chronicle of North-country Lore and Legend. Newcastle upon Tyne: Walter Scott: 41–42.

- 1 2 Kidson, Frank (10 January 1891). "Old Songs and Airs: Melodies Once Popular in Yorkshire". Leeds Mercury Weekly Supplement: 5.

- 1 2 3 Minto, W., ed. (1892). Autobiographical Notes on the Life of William Bell Scott, vol. i. London: James R. Osgood, McIlvaine & Co. pp. 186–187.

- ↑ Cole, Pamela McArthur (January–March 1900). "The Twelve Days of Christmas; A Nursery Song". Journal of American Folk-Lore. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. xiii (xlviii): 229–230.; "obtained from Miss Nichols (Salem, Mass., about 1800)"

- 1 2 Sharp (1905), pp. 52–55

- ↑ "Old Carols". Leicester Daily Post. 26 December 1907. p. 3. – via britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk (subscription required)

- ↑ Chambers, Robert (1842). Popular Rhymes, Fireside Stories, and Amusements, of Scotland. Edinburgh: William and Robert Chambers. pp. 49–50.

- ↑ Chambers, Robert (1847). Popular Rhymes of Scotland (third ed.). Edinburgh: W. and R. Chambers. pp. 198–199.

- ↑ "Dictionary of the Scots Languages". Retrieved 15 March 2017.

- ↑ "Another Counting Song". Retrieved 7 December 2015.

- ↑ "The twelve Days of Christmas - Set of mint". Posta. Retrieved 28 January 2021.

- ↑ "Archived copy" (PDF). luf.ht.lu.se. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 October 2021. Retrieved 12 January 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ↑ https://katalog.visarkiv.se/lib/views/rec/ShowRecord.aspx?id=697897 (7:00-10:00)

- ↑ Ruth Rubin, Voices of a People: The Story of Yiddish Folksong, ISBN 0-252-06918-8, p. 465

- 1 2 de Coussemaker, E[dmond] (1856). Chants Populaires des Flamands de France. Gand: Gyselynck. pp. 133–135. hdl:2027/hvd.32044040412256.

- ↑ Durieux, A.; Bruyelle, A. (1864). Chants et Chansons Populaires du Cambresis. Cambrai. p. 127. hdl:2027/uc1.a0000757377.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ For another version with a melody, see Hamy, E. T. (15 January 1892). "Le Premier Mois de l'Année". Revue des Traditions Populaires. Paris. 7 (1): 34–36.

- ↑ Durielles & Bruyelles, op. cit., p. 127: "Petit fromage de Maroilles (arrondissement d'Avesnes)".

- ↑ Rolland, Eugène (1877). Faune Populaire de la France. Paris: Maisonneuve. p. 336.

Les jeunes perdrix de l'année sont appelées [...] PERTRIOLLE f. Flandres, Vermesse.

- ↑ Mark Lawson-Jones, Why was the Partridge in the Pear Tree?: The History of Christmas Carols, 2011, ISBN 0-7524-7750-1

- ↑ "Twelfth Night noun - Definition, pictures, pronunciation and usage notes". Oxford Advanced Learner's Dictionary. Retrieved 9 January 2021.

- ↑ Pinks, William J. (1881). Wood, Edward J. (ed.). History of Clerkenwell (second ed.). London: Charles Herbert. p. 678.

- 1 2 Yoffie (1949), p. 400.

- 1 2 Opie and Opie (1951), pp. 122–23.

- 1 2 Brewster, Paul G. (1940). Ballads and Songs of Indiana. Bloomington: Indiana University. p. 354.

- 1 2 Poston, Elizabeth (1970). Second Penguin Book of Christmas Carols. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books. p. 31. ISBN 9780140708387.

- ↑ For the medieval text, see Brown, Carleton (1932). English Lyrics of the XIIIth Century. London: Oxford University Press. pp. 39–41. or Greg, W. W. (1913). "A Ballad of Twelfth Day". Modern Language Review. Modern Humanities Research Association. 8 (1): 64–67. doi:10.2307/3712650. JSTOR 3712650.

- ↑ Yoffie (1949), p. 399

- ↑ Cauthen, I. B. (1949). "The Twelfth Day of December: Twelfth Night II.iii.91". Studies in Bibliography. Bibliographical Society of the University of Virginia. ii: 182–185.

- ↑ "The song "The Twelve Days of Christmas" was created as a coded reference". Snopes.com. 15 December 2008. Retrieved 10 December 2011.

There is absolutely no documentation or supporting evidence for [the claim that the song is a secret Catholic catechism] whatsoever, other than mere repetition of the claim itself. The claim appears to date only to the 1990s, marking it as likely an invention of modern day speculation rather than historical fact.

- ↑ Husk (1864), p. 181.

- ↑ Gomme (1898), p. 319.

- 1 2 3 4 Sharp, Gilchrist & Broadwood (1916), p. 280.

- ↑ Brice, Douglas (1967). The Folk-Carol of England. London: Herbert Jenkins. p. 89.

- ↑ Sandys, William (1847). Festive Songs of the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries. Vol. 23. London: Percy Society. p. 74.

- ↑ Sharp (1905), p. 74

- 1 2 Baring-Gould, William S.; Baring-Gould, Ceil (1962). The Annotated Mother Goose. New York: Bramhall House. pp. 196–197. OCLC 466911815.

- ↑ Also spelled "colley" or "collie"

- ↑ Shahn, Ben (1951). A Partridge in a Pear Tree. New York: Museum of Modern Art.

- ↑ Aled Jones, Songs of Praise, BBC, 26 December 2010.

- ↑ Pape, Gordon, and Deborah Kerbel. Quizmas Carols: Family Trivia Fun with Classic Christmas Songs. New York: A Plume Book, October 2007. ISBN 978-0-452-28875-1

- ↑ McKellar, High D. (October 1994). "The Twelve Days of Christmas". The Hymn. 45 (4).

In any case, really evocative symbols do not allow of [sic] definitive explication, exhausting all possibilities. I can at most report what this song's symbols have suggested to me in the course of four decades, hoping thereby to start you on your own quest.

- ↑ Gilhooley, (Rev.) James (28 December 1987). "Letter to the Editor: True Love Revealed". The New York Times. Retrieved 23 December 2013.

- ↑ Fr. James Gilhooley, "Those Wily Jesuits: If you think 'The Twelve Days of Christmas'is just a song, think again," Our Sunday Visitor, v. 81, no. 34 (20 December 1992), p. 23.

- ↑ Mikkelson, David (16 December 2000). "The Twelve Days of Christmas". Snopes. Retrieved 30 December 2023.

- ↑ "The Marie Hall Concerts at Exeter". Western Times. Exeter: 2. 24 April 1905.

- ↑ "Concerts". Times. London: 13. 5 April 1906.

- ↑ Austin (1909)

- ↑ Registered for US copyright in August 1909; see "Twelve (The) Days of Christmas". Catalogue of Copyright Entries Part 3: Musical Compositions. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office. n.s. 4 (44–47): 982. November 1909.

- ↑ "Reviews". Musical Times. 50 (801): 722. 1 November 1909.

- ↑ "New Music". Manchester Courier: 11. 18 December 1909.

- ↑ Austin, Frederic (1955). The Twelve Days of Christmas: Traditional (Song for Low Voice). Novello. p. 2. Novello 13056.. With the exception of the footnote, outer covers, and position of the dedication, the 1955 and 1909 publications are typographically identical; both are assigned the same Novello catalogue number of 13056.

- ↑ Routley, Erik (1961). University Carol Book. Brighton: H. Freeman & Co. pp. 268–269. OCLC 867932371. Though Erik Routley was the overall editor of this volume, its arrangement of "Twelve Days of Christmas" was made by Gordon Hitchcock, who is thus the likely source of this statement.

- ↑ Richard Austin, the son of Frederic Austin, had published an arrangement the previous year: Austin, Frederic; Austin, Richard (1960). The Twelve Days of Christmas: a traditional song arranged for unison voices & piano by Frederic Austin, accompaniment simplified by Richard Austin. London: Novello. OCLC 497413045. Novello School Songs 2039..

- ↑ Rutter, John (1967). Eight Christmas Carols: Set 2. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 15. OCLC 810573578.

Melody for "Five gold rings" added by Frederic Austin, and reproduced by permission of Novello & Co. Ltd.

- ↑ Keyte, Hugh; Parrott, Andrew (1992). New Oxford Book of Carols. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. xxxiii. ISBN 0-19-353323-5.

Melody for 'Five gold rings' (added by Frederick [sic] Austin)

- 1 2 3 Barry (1905), p. 58. See also p. 50.

- ↑ Barry (1905), p. 57.

- ↑ Sharp et al. (1916), p. 278

- ↑ "The Christmas Presents (Roud Folksong Index S201515)". The Vaughan Williams Memorial Library. Retrieved 9 December 2020.

- ↑ "Twelve Days of Christmas (Roud Folksong Index S254563)". The Vaughan Williams Memorial Library. Retrieved 9 December 2020.

- ↑ "Twelve Days of Christmas (Roud Folksong Index S254559)". The Vaughan Williams Memorial Library. Retrieved 9 December 2020.

- ↑ "Twelve Days of Christmas (Roud Folksong Index S254562)". The Vaughan Williams Memorial Library. Retrieved 9 December 2020.

- ↑ "Twelve Days of Christmas (Roud Folksong Index S254561)". The Vaughan Williams Memorial Library. Retrieved 9 December 2020.

- ↑ "Twelve Days of Christmas (Roud Folksong Index S163946)". The Vaughan Williams Memorial Library. Retrieved 9 December 2020.

- ↑ "Days of Christmas (Roud Folksong Index S407817)". The Vaughan Williams Memorial Library. Retrieved 9 December 2020.

- ↑ "CONTENTdm". digitalcollections.uark.edu. Retrieved 9 December 2020.

- ↑ "A Bing Crosby Discography". BING magazine. International Club Crosby. Retrieved 21 May 2017.

- ↑ DVD An Audience with... Jasper Carrott

- ↑ Jasper Carrott - 12 Days Of Christmas, 10 September 1977, retrieved 21 December 2022

- ↑ Liner notes from Allan Sherman: My Son, The Box (2005)

- ↑ "Allan Sherman Discography". Povonline.com. 30 November 1924. Archived from the original on 16 December 2011. Retrieved 5 December 2011.

- ↑ Knight, Hilary (1963). Christmas Nutshell Library. Harper and Row Publishers. ISBN 9780060231651.

- 1 2 Knight, Hilary (2004). A firefly in a fir tree: A carol for mice. New York: Katherine Tegen Books. Retrieved 27 December 2017 – via Internet Archive.

- ↑ "Sinatra Family Twelve Days of Christmas". Caroling Corner. Retrieved 5 December 2011.

- ↑ Obituary: "R.I.P. FAY MCKAY". Las Vegas Review-Journal, 5 April 2008.

- ↑ "... and yet Another Partridge in a Pear Tree". Radio Times (2824): 31. 22 December 1977.

- ↑ Sibley, Brian. "And Another Partridge in a Pear Tree". Brian Sibley: The Works. Retrieved 15 December 2014.

- ↑ "And Yet Another Partridge in a Pear Tree". BBC Radio 4 Extra. Retrieved 26 January 2015.

- ↑ John Denver and the Muppets: A Christmas Together (1979). Retrieved 24 January 2009.

- ↑ "A Pukeko in a Ponga Tree". Folksong.org.nz. 1 December 2000. Retrieved 5 December 2011.

- ↑ "A Pukeko in a Ponga Tree". Maori-in-Oz. Archived from the original on 5 September 2012. Retrieved 5 December 2011.

- ↑ The Mad Music Archive. Retrieved 25 December 2008.

- ↑ dalty_smilth (3 December 1993). "The Twelve Days of Christmas (TV Movie 1993)". IMDb. Retrieved 7 December 2015.

- ↑ VeggieTales Official, VeggieTales Christmas Party: The 8 Polish Foods of Christmas, archived from the original on 14 December 2021, retrieved 9 December 2018

- ↑ "Let It Snow, Baby... Let It Reindeer". iTunes. 23 October 2007. Retrieved 13 December 2016.

- ↑ CMT.com: Shows: The 12 Days of Redneck Christmas. Retrieved 25 December 2008.

- ↑ "It's a Pony Kind of Christmas". iTunes. Retrieved 7 December 2015.

- ↑ "FRANK KELLY | full Official Chart History | Official Charts Company". www.officialcharts.com. Retrieved 22 December 2021.

- ↑ Irish chart site. Archived 16 August 2016 at the Wayback Machine Type Frank Kelly in the search box to retrieve the data

- ↑ Kent, David (1993). Australian Chart Book 1970–1992 (illustrated ed.). St Ives, N.S.W.: Australian Chart Book. p. 164. ISBN 0-646-11917-6.

- ↑ 'Creature Comforts': A Very Human Animal Kingdom - The Washington Post; 20 October 2006

- ↑ Catching Up With Benny Grunch, New Orleans Magazine, December 2013

- ↑ 12 Yats of Christmas, YouTube, Uploaded on 24 December 2007

- ↑ "SCC: Map Archives". Classic Battle.net. 23 December 1999. Retrieved 27 May 2017.

- ↑ CarbotAnimations (14 December 2013). "StarCrafts Christmas Special 2013 the Twelve Days of StarCrafts". YouTube. Retrieved 27 May 2017.

- ↑ "Twelve Days of Christmas". www.huapala.org. Retrieved 22 December 2021.

- ↑ Berger, John (19 December 2010). "'12 Days' Hawaiian-style song still fun after 50 years". Honolulu Star-Advertiser. Retrieved 22 December 2021.

- ↑ The 12 Days of Christmas Eddie's Math and Calculator. Accessed December 2013

- ↑ Tetrahedral (or triangular pyramidal) numbers The 12th tetrahedral number is 364. Accessed August 2020

- ↑ Spinner, Jackie (20 December 2007). "Two Turtledoves, My Love". Washington Post. Retrieved 5 December 2011.

- ↑ Olson, Elizabeth (25 December 2003). "The '12 Days' Index Shows a Record Increase". The New York Times. Retrieved 5 December 2011.

- ↑ "2015 PNC Christmas Price Index". PNC Financial Services. Archived from the original on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 5 December 2015.

- ↑ "2015 PNC Christmas Price Index". PNC Financial Services. 5 December 2015. Archived from the original on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 5 December 2015.

- ↑ Mitchell, Kathy; Sugar, Marcy (25 December 2014). "The 12 Days of Christmas Adjusted for Inflation". Creators Syndicate. Retrieved 25 December 2014.

- ↑ "The 12 Days of Christmas – a lesson in how a complex appraisal can go astray". Fulcrum.com. Retrieved 14 December 2011.

- ↑ Knuth, Donald (Summer 1977). "The Complexity of Songs". SIGACT News. 27 (4): 17–24. doi:10.1145/358027.358042. S2CID 207711569.

- ↑ Mike Markowski. "xmas.c". Retrieved 12 December 2022.

Bibliography

- Anonymous (c. 1800). Mirth without mischief Comtaining [sic] The twelve days of Christmas; The play of the gaping-wide-mouthed-wadling-frog; Love and hatred; ... and Nimble Ned's alphabet and figures. London: C. Sheppard.

- Austin, Frederic, (arr.) (1909). The Twelve Days of Christmas (Traditional Song). London: Novello. OCLC 1254007259. Novello 13056.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Barry, Phillips (January 1905). "Some Traditional Songs". Journal of American Folk-Lore. Boston: Houghton, Mifflin and Company. XVIII (68): 49–59. doi:10.2307/534261. JSTOR 534261.

- Eckenstein, Lina (1906). "Chapter XII: Chants of Numbers". Comparative Studies in Nursery Rhymes. London: Duckworth. pp. 61–65.

- Gomme, Alice Bertha (1898). The Traditional Games of England, Scotland, and Ireland. Vol. ii. London: David Nutt. pp. 315–321.

- Husk, William Henry, ed. (1864). Songs of the Nativity. London: John Camden Hotten. pp. 181–185.

- Opie, Peter and Iona, eds. The Oxford Dictionary of Nursery Rhymes. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1951, pp. 122–230, ISBN 0-19-869111-4.

- Sharp, Cecil J.; Marson, Charles L. (1905). Folk Songs from Somerset (Second Series). Taunton: Simpkin. hdl:2027/inu.39000005860007.

- Sharp, Cecil J.; Gilchrist, A. G.; Broadwood, Lucy E. (November 1916). "Forfeit Songs; Cumulative Songs; Songs of Marvels and of Magical Animals". Journal of the Folk-Song Society. 5 (20): 277–296.

- Yoffie, Leah Rachel Clara (October–December 1949). "Songs of the 'Twelve Numbers' and the Hebrew Chant of 'Echod mi Yodea'". The Journal of American Folklore. 62 (246): 399–401. doi:10.2307/536580. JSTOR 536580.

External links

- Free scores of The Twelve Days of Christmas in the Choral Public Domain Library (ChoralWiki)

- Free online simple melody score for all verses (as JPEGs or a PDF file) in English and Esperanto: "The Twelve Days of Christmas / La Dek Du Tagoj de Kristnasko"