The two–Mona Lisa theory is a longstanding theory proposed by various historians, art experts, and others that Leonardo da Vinci painted two versions of the Mona Lisa.[2][3][4] Several of these experts have further concluded that examination of historical documents indicates that one version was painted several years before the second.

The journalist Dianne Hales has noted that "the two–Mona Lisa theory has been around a long time",[2] observing that the sixteenth-century painter and art theorist Gian Paolo Lomazzo identifies two versions of the painting in his 1584 Treatise on Painting.[2] The theory itself may be impossible to definitively prove or disprove, but proponents of the theory highlight a number of pieces of documentary and physical evidence. Among these is the fact that there are several paintings of which Leonardo is known to have painted two versions, and historical accounts such as Lomazzo's writing suggesting that Leonardo similarly worked on two paintings, a Gioconda and a Mona Lisa. Furthermore, various accounts contain inconsistencies and incompatibilities with respect to the dates when Leonardo began and ended work on the painting, by whom it was commissioned, the state of completion in which it was left, and what ultimately became of it. These inconsistencies and incompatibilities are asserted to be broadly resolved with the explanation that there were two versions of the painting having different dates of initiation and states of completion, painted for different patrons, and having different profiles and fates.

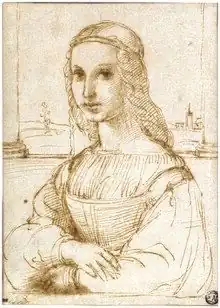

Also cited as a key piece of evidence is a contemporaneous sketch of the painting by Raphael, who observed the painting while visiting Leonardo's studio. The sketch contains characteristics differing from the Mona Lisa in the Louvre, including prominent columns that were initially argued to have been trimmed from the original. However, in 1993 it was demonstrated that the painting in the Louvre had never been trimmed, bolstering claims that Raphael saw a different version of the painting. Other descriptions by eyewitnesses and others living in the period have also been read as indicating that Leonardo painted two paintings of the subject of the Mona Lisa, with several characteristics differing from the painting in the Louvre.

The author John R. Eyre made an extensive case for the theory in his 1915 Monograph on Leonardo da Vinci's Mona Lisa,[3] and Léon Roger-Milès made a similar case in his 1923 book, Leonard de Vinci et les Jocondes.[4] Several more recent examinations of the evidence have led other authors to similar conclusions. While it is possible that a first version was produced by Leonardo and later lost or destroyed, proponents of the theory have identified a number of existing alternative versions of the Mona Lisa as candidates for having also been painted by Leonardo. These include versions more similar to the original such as the Prado Mona Lisa, but more particularly those versions that closely resemble Raphael's sketch and other historical accounts, such as the Vernon Mona Lisa (which is no longer considered a candidate after tests showed that it was painted after Leonardo's death), and the Isleworth Mona Lisa, the latter having received the most substantial support.[5][6][7][8][9]

Evidence cited for the theory

Propensity for painting multiple versions of works

A number of authors have noted that Leonardo often painted two versions of his works, and also often left works unfinished, leaving his students to complete the missing portions. For example, Frank Zöllner wrote of Leonardo's two versions of the Virgin of the Rocks,[10] and Eyre, in his 1915 monograph, wrote that Leonardo "almost invariably commenced two versions of each of his works, which he rarely finished", citing the Virgin of the Rocks along with two versions of Saint John the Baptist and of Leda and the Swan, and two versions each of drawings of Isabella d'Este, the Adoration of the Magi, and Saint Anne.[3]: 12

References to multiple versions of the Mona Lisa

Dianne Hales quotes the sixteenth-century painter and art theorist Gian Paolo Lomazzo as identifying two versions of the painting: "In 1584, in his Treatise on Painting, the Florentine artist and chronicler Giovanni Paolo Lomazzo, a supposed acquaintance of Leonardo's longtime secretary Melzi, wrote that 'the two most beautiful and important portraits by Leonardo are the Mona Lisa and the Gioconda'".[2] Another statement considered as evidence for this purpose was made by Fra Pietro da Novellara in a 1501 letter to Isabella d'Este, Marchesa of Mantua, detailing Leonardo's activities from a visit to his studio. Fra Pietro states in the letter that "[t]wo of his pupils are painting portraits, and he touches them up from time to time".[11][12] Eyre and Eugène Müntz both discuss Fra Pietro's letter, with Müntz deeming the subjects unknown,[13] and Eyre concluding that these were portraits of Lisa del Giocondo.

Raphael's sketch

A number of experts have argued that Leonardo made two versions based on the differences in details in Raphael's sketch.[1][7][8] Circa 1505,[1] Raphael executed a pen-and-ink sketch, in which columns flanking the subject are substantially more apparent. Experts universally agree that this sketch was based on Leonardo's portrait.[14][7][9] Other later copies of the Mona Lisa, such as those in the National Museum of Art, Architecture and Design and The Walters Art Museum, also display large flanking columns. As a result, it was thought that the Mona Lisa had been trimmed.[15][16][17][18] However, by 1993, Frank Zöllner observed that the painting surface had never been trimmed;[19] this was confirmed through a series of tests in 2004.[20] In view of this, the art historian Vincent Delieuvin, curator of sixteenth-century Italian painting at the Louvre, states that the sketch and these other copies must have been inspired by another version,[21] while Zöllner states that the sketch may be after another Leonardo portrait of the same subject.[19]

Disparities in dates of production and completion

Disparate dates proposed for the initiation and completion or abandonment of the Mona Lisa are claimed to indicate that there were actually two different paintings worked on at different times, with one version being begun in 1503 and left unfinished, and the Louvre Mona Lisa being begun after 1513. Specifically, it is believed by some that Leonardo da Vinci had begun working on a portrait of Lisa del Giocondo, the model of the Mona Lisa, in Florence by October 1503.[22] [23][24] Although the Louvre states that it was "doubtless painted between 1503 and 1506",[25] Leonardo experts such as Carlo Pedretti and Alessandro Vezzosi are of the opinion that the Louvre painting is characteristic of Leonardo's style in the final years of his life, post-1513.[26][27] Other academics argue that historical documentation indicates that Leonardo would have painted the work in the Louvre from 1513.[28]

In 2005, a scholar at Heidelberg University discovered a marginal note in a 1477 printing of a volume by the ancient Roman philosopher Cicero. The note was dated October 1503, and was written by Leonardo's contemporary Agostino Vespucci. This note likens Leonardo to the renowned Greek painter Apelles, who is mentioned in the text, and states that Leonardo was at that time working on a painting of Lisa del Giocondo.[22] In response, Delieuvin stated "Leonardo da Vinci was painting, in 1503, the portrait of a Florentine lady by the name of Lisa del Giocondo. About this we are now certain. Unfortunately, we cannot be absolutely certain that this portrait of Lisa del Giocondo is the painting of the Louvre".[29]

The art historian Martin Kemp, while doubting the two-painting theory, nevertheless notes difficulties in confirming the dates with certainty,[30] and the sixteenth-century biographer Giorgio Vasari wrote of Leonardo's work on the Mona Lisa that "after he had lingered over it four years, [he] left it unfinished",[14] though the painting in the Louvre appears to be a finished piece. Proponents of the theory explain that the hypothetical first portrait, displaying prominent columns, would have been commissioned by Giocondo circa 1503, of a younger sitter (Lisa del Giocondo being 23 years old in 1503), and left unfinished in the possession of Leonardo's pupil and assistant Salaì until Salaì's death in 1524. The second, commissioned by Giuliano de' Medici circa 1513, would have been sold by Salaì to Francis I of France in 1518[lower-alpha 1] and is the one in the Louvre today.[9][7][8][31] Notably, even those who believe that there was only one true Mona Lisa have been unable to agree between the two aforementioned fates, or to otherwise account for the incompatibility of the facts of record with only one painting.[30][32][33]

Disparities over the commission

Different sources provide inconsistent information about the identity of the patron for whom the Mona Lisa was painted. In his 1923 book, Leonard de Vinci et les Jocondes, Léon Roger-Milès argues that Leonardo actually painted at least two versions of the Mona Lisa, including one for Francesco del Giocondo, and another for Giuliano de' Medici.[4] According to Vasari, the painting was created for the model's husband, Francesco del Giocondo.[34][35] However, the record of an October 1517 visit by Louis d'Aragon states that the Mona Lisa was executed for the deceased Medici, Leonardo's steward at the Belvedere Palace between 1513 and 1516.[36][37][lower-alpha 2]—though some have suspected this to be an error, hypothesizing that this refers to yet another portrait by Leonardo "of which no record and no copies exist".[38][lower-alpha 3]

Scholars have also developed several alternative views as to the subject of the painting, with some historically having argued that Lisa del Giocondo was the subject of a different Leonardo portrait, and identifying at least four other paintings as the Mona Lisa referenced by Vasari.[39][40] Several other women have been proposed as the subject of the painting in the Louvre.[41] Isabella of Aragon,[42] Cecilia Gallerani,[43] Costanza d'Avalos, Duchess of Francavilla,[41] Isabella d'Este, Pacifica Brandano or Brandino, Isabella Gualanda, Caterina Sforza, Bianca Giovanna Sforza—even feminized versions of Salaì and Leonardo himself—are all among the list of posited models portrayed in the painting.[44][45][46] Based on this assertion, it is proposed that Leonardo painted a different painting actually depicting Lisa del Giocondo.

Eyebrows and eyelashes

One previously cited item that appears to have been resolved is the state of the eyebrows or eyelashes of the Mona Lisa. Eyre noted that the absence of these features in the Louvre's Mona Lisa is contrary to Vasari's description of the eyebrows on the painting, that '"[t]hey spring from the flesh, their varying thickness, the manner in which they curve according to the pores of the skin, could not have been rendered in a more natural fashion".[3]: 22–23 Some researchers accounted for this disparity by asserting that the subject never had eyebrows, and that it was common at this time for genteel women to pluck these hairs, as they were considered unsightly.[47][48][3]: 23 In 2007, however, the French engineer Pascal Cotte announced that his ultra–high resolution scans of the painting provide evidence that the Mona Lisa was originally painted with eyelashes and with visible eyebrows, but that these had gradually disappeared over time, perhaps as a result of overcleaning.[49] Vasari also described red lips,[50] of which Cotte was unable to find traces in the Louvre painting. Cotte discovered that the painting in the Louvre had been reworked several times, with changes made to the size of the sitter's face and the direction of her gaze. He also found that in one layer the subject was depicted wearing numerous hairpins and a headdress adorned with pearls which was later scrubbed out and overpainted.[51]

Other versions

.jpg.webp)

It is possible that a first version of the Mona Lisa was produced and then lost or destroyed. However, a number of existing paintings have been identified as possibly being this first version. The most widely endorsed contender is the Isleworth Mona Lisa, which had been examined by a number of experts in the 1910s and 1920s, and was later hidden in a Swiss bank vault for 40 years before being unveiled to the public on September 27, 2012.[52] The Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich has dated the piece to Leonardo's lifetime, and an expert in sacred geometry has found it to conform to the artist's basic line structures.[53][54] It also has columns similar to those in the sketch made by Raphael, and the red lips described by Vasari. In 1988, the physicist John F. Asmus, who pioneered laser-restoration techniques for Renaissance art, and who had previously examined the Mona Lisa in the Louvre for this purpose, published a computer image processing study concluding that the brush strokes of the face in the Isleworth Mona Lisa were performed by the same artist responsible for the brushstrokes of the face of the Mona Lisa in the Louvre.[55][56]

By the 1970s, Peregrine Cust, 6th Baron Brownlow, also came into possession of a painting which he believed to be another version of the Mona Lisa, and to also have been painted by Leonardo.[57] Brownlow and Henry F. Pulitzer, owner of the Isleworth Mona Lisa at that time, genially disputed who had the "real" Mona Lisa in the press,[57] and both offered to show their respective Mona Lisa paintings at a London exhibition in 1972.[58][59]

Another claimed version is in the Vernon collection.[60] The Vernon Mona Lisa, however, dates from around 1616, though it also has columns, and was itself originally part of the collection at the Louvre. It was given to Joshua Reynolds by the Duke of Leeds around 1790, in exchange for a Reynolds self-portrait. This version was included in an 1824 "Account of the Principal Pictures belonging to the Nobility and Gentry of England", which lists "The Mona Lisa sitting on a Chair" as a painting by "Lionardo da Vinci"; it was then owned by Sir Abraham Hume. The account describes the background as "a Landscape with a Bridge", and states that "[i]t is not known how this portrait was brought to England".[61] Reynolds thought it to be the real painting and the French one a copy, which was later deemed to have been disproved. It is, however, useful in that it was copied when the original's colors were far brighter than they are now, and so it gives some sense of the original's appearance "as new". It remains in a private collection, but was exhibited in 2006 at the Dulwich Picture Gallery.[62]

In 2012 the Museo del Prado in Madrid announced that it had discovered and almost fully restored a copy of the painting by a pupil of Leonardo, very possibly painted alongside the master.[63] The copy gives a better indication of what the portrait looked like at the time, as the varnish on the original has become cracked and yellowed with age.[64] The German imaging researchers Claus-Christian Carbon of the University of Bamberg and Vera Hesslinger of the University of Mainz performed further analysis of the Prado version, comparing it to Leonardo's Mona Lisa, and in 2014 speculated that, based on perspective analysis of key features in the images, the two images were painted at the same time from slightly different viewpoints. They further proposed that two images may therefore form a stereoscopic pair, creating the illusion of three-dimensional depth, when viewed side-by-side.[65] However, a study published in 2017 has demonstrated that this stereoscopic pair in fact gives no reliable stereoscopic depth.[66]

Professor Salvatore Lorusso, who has written several papers and articles comparing these paintings and others, including the Mona Lisa with Columns in Saint Petersburg, and the Oslo Mona Lisa, supported the Isleworth Mona Lisa as one of two original versions by Leonardo, while concluding that the Prado Mona Lisa is likely to have been by one of Leonardo's more talented students, and that the Vernon Mona Lisa was a copy done section-by-section, "probably painted by a French court artist in Fontainebleau or a visiting artist at the beginning of the 17th century".[7]

See also

Notes

- ↑ Along with The Virgin and Child with Saint Anne and Saint John the Baptist

- ↑ "... Messer Lunardo Vinci [sic] ... showed His Excellency three pictures, one of a certain Florentine lady done from life at the instance of the late Magnificent, Giuliano de' Medici."[38]

- ↑ "Possibly it was another portrait of which no record and no copies exist—Giuliano de' Medici surely had nothing to do with the Mona Lisa—the probability is that the secretary, overwhelmed as he must have been at the time, inadvertently dropped the Medici name in the wrong place."[38]

References

- 1 2 3 Becherucci, Luisa (1969). The Complete Work of Raphael. New York: Reynal and Co., William Morrow and Company. p. 50.

- 1 2 3 4 Dianne Hales, Mona Lisa: A Life Discovered (2014), p. 251.

- 1 2 3 4 5 John R. Eyre, Monograph on Leonardo da Vinci's Mona Lisa (1915).

- 1 2 3 Christian Gálvez, Gioconda descodificada: Retrato de la mujer del Renacimiento (2019), p. 195, quoting Léon Roger-Milès, Leonard de Vinci et les Jocondes (1923).

- ↑ Eyre, John (1923). The Two Mona Lisas: which was Giacondo's picture?: ten direct, distinct, and decisive data in favour of the Isleworth version, and some recent Italian expert opinions on it. London, England: J. M. Ouseley & Son. OCLC 19335669.

- ↑ Chappelow, A. C. (July 1, 1956). "The Isleworth Mona Lisa". Apollo Magazine. p. 28.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Lorusso, Salvatore; Natali, Andrea (2015). "Mona Lisa: A comparative evaluation of the different versions and copies". Conservation Science. 15: 57–84. Retrieved 26 July 2017.

- 1 2 3 Boudin de l'Arche, Gerard (2017). A la recherche de Monna Lisa. Cannes, France: Edition de l'Omnibus. ISBN 9791095833017.

- 1 2 3 Isbouts, Jean-Pierre; Heath-Brown, Christopher (2013). The Mona Lisa Myth. Santa Monica, California: Pantheon Press. ISBN 978-1492289494.

- ↑ Frank Zöllner, Leonardo da Vinci, 1452–1519 (2000), p. 30.

- ↑ Letter from Fra Pietro da Novellara to Isabella d'Este, Marchesa of Mantua (March 22, 1501), in John R. Eyre, Monograph on Leonardo da Vinci's Mona Lisa (1915), p. 16-17.

- ↑ E. L. Scott, "Yet Another "Mona Lisa" Adds to Mystery of Louvre Picture", Deseret News (February 14, 1914), p. 25.

- ↑ Eugène Müntz, Léonard da Vinci, l'artiste, le penseur, le savant, vol. 2 (1899), p. 11.

- 1 2 Clark, Kenneth (March 1973). "Mona Lisa". The Burlington Magazine (vol 115 ed.). 115 (840): 144–151. ISSN 0007-6287. JSTOR 877242.

- ↑ Friedenthal, Richard (1959). Leonardo da Vinci: a pictorial biography. New York: Viking Press.

- ↑ Kemp, Martin (1981). Leonardo: The marvelous works of nature and man. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0674524606.

- ↑ Bramly, Serge (1995). Leonardo: The artist and the man. London: Penguin books. ISBN 978-0140231755.

- ↑ Marani, Pietro (2003). Leonardo: The complete paintings. New York: Harry N. Abrams. ISBN 978-0810991590.

- 1 2 Zollner, Frank (1993). "Leonardo da Vinci's portrait of Mona Lisa de Giocondo" (PDF). Gazette des Beaux-Arts. 121: 115–138. Retrieved August 3, 2017.

- ↑ Mohen, Jean-Pierre (2006). Mona Lisa: inside the Painting. Abrams Books. p. 128. ISBN 978-0-8109-4315-5.

- ↑ Delieuvin, Vincent; Tallec, Olivier (2017). What's so special about Mona Lisa. Paris: Editions du musée du Louvre. ISBN 978-2-35031-564-5.

- 1 2 "Mona Lisa – Heidelberg discovery confirms identity". University of Heidelberg. Archived from the original on 5 November 2013. Retrieved 4 July 2010.

- ↑ Delieuvin, Vincent (15 January 2008). "Télématin". Journal Télévisé. France 2 Télévision.

- ↑ Wiesner-Hanks, Merry E. (2005). An Age of Voyages, 1350–1600. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 26. ISBN 978-0-19-517672-8.

- ↑ "Mona Lisa – Portrait of Lisa Gherardini, wife of Francesco del Giocondo". Musée du Louvre. Archived from the original on 30 July 2014. Retrieved 11 March 2012.

- ↑ Pedretti, Carlo (1982). Leonardo, a study in chronology and style. Johnson Reprint Corporation. ISBN 978-0384452800.

- ↑ Vezzosi, Alessandro (2007). "The Gioconda mystery – Leonardo and the 'common vice of painters'". In Vezzosi; Schwarz; Manetti (eds.). Mona Lisa: Leonardo's hidden face. Polistampa. ISBN 9788859602583.

- ↑ Asmus, John F.; Parfenov, Vadim; Elford, Jessie (28 November 2016). "Seeing double: Leonardo's Mona Lisa twin". Optical and Quantum Electronics. 48 (12): 555. doi:10.1007/s11082-016-0799-0. S2CID 125226212.

- ↑ Delieuvin, Vincent (15 January 2008). "Télématin". Journal Télévisé. France 2 Télévision.

- 1 2 Kemp 2006, pp. 261–262

- ↑ Louvre Museum. "Mona Lisa". louvre.fr. Retrieved August 3, 2017.

- ↑ Kemp, Martin; Pallanti, Giuseppe (2017). Mona Lisa: The people and the painting. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198749905.

- ↑ Jestaz, Bertrand (1999). "Francois 1er, Salai, et les tableaux de Léonard". Revue de l'Art (in French). 76: 68–72. doi:10.3406/rvart.1999.348476.

- ↑ Vasari, Giorgio (1550). Le Vite de' più eccellenti pittori, scultori, ed architettori. Florence, Italy: Lorenzo Torrentino.

- ↑ Louvre Museum. "Mona Lisa". louvre.fr. Retrieved August 3, 2017.

- ↑ De Beatis, Antonio (1979) [1st pub.:1517]. Hale, J.R.; Lindon, J.M.A. (eds.). The travel journal of Antonio de Beatis: Germany, Switzerland, the Low Countries, France and Italy 1517–1518. London, England: Haklyut Society.

- ↑ Bacci, Mina (1978) [1963]. The Great Artists: Da Vinci. Translated by Tanguy, J. New York: Funk & Wagnalls.

- 1 2 3 Wallace, Robert (1972) [1966]. The World of Leonardo: 1452–1519. New York: Time-Life Books. pp. 163–64.

- ↑ Stites, Raymond S. (January 1936). "Mona Lisa—Monna Bella". Parnassus. 8 (1): 7–10, 22–23. doi:10.2307/771197. JSTOR 771197.

- ↑ Littlefield, Walter (1914). "The Two "Mona Lisas"". The Century: A Popular Quarterly. 87: 525.

- 1 2 Wilson, Colin (2000). The Mammoth Encyclopedia of the Unsolved. New York, New York: Carroll & Graf Publishers. pp. 364–366. ISBN 978-0-7867-0793-5.

- ↑ Debelle, Penelope (25 June 2004). "Behind that secret smile". The Age. Melbourne. Archived from the original on 25 November 2013. Retrieved 6 October 2007.

- ↑ Johnston, Bruce (8 January 2004). "Riddle of Mona Lisa is finally solved: she was the mother of five". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 11 October 2007. Retrieved 6 October 2007.

- ↑ Chaundy, Bob (29 September 2006). "Faces of the Week". BBC. Archived from the original on 3 August 2014. Retrieved 5 October 2007.

- ↑ Nicholl, Charles (28 March 2002). "The myth of the Mona Lisa". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 5 September 2008. Retrieved 6 October 2007.

- ↑ Kington, Tom (9 January 2011). "Mona Lisa backdrop depicts Italian town of Bobbio, claims art historian". The Guardian. London.

- ↑ Turudich, Daniela (2003). Plucked, Shaved & Braided: Medieval and Renaissance Beauty and Grooming Practices 1000–1600. North Branford, Connecticut: Streamline Press. p. 198. ISBN 978-1-930064-08-9.

- ↑ McMullen, Roy (1976). Mona Lisa: The Picture and the Myth. Macmillan Publishers. ISBN 978-0-333-19169-9.

- ↑ Holt, Richard (22 October 2007). "Solved: Why Mona Lisa doesn't have eyebrows". The Daily Telegraph. UK. Archived from the original on 4 April 2010. Retrieved 11 March 2010.

- ↑ Douglas Mannering, The Art of Leonardo da Vinci (1981), p. 52.

- ↑ Ghose, Tia (9 December 2015). "Lurking Beneath the 'Mona Lisa' May Be the Real One". Livescience.com. Archived from the original on 11 December 2015.

- ↑ "Second Mona Lisa Unveiled for First Time in 40 Years". ABC News. Retrieved September 28, 2012.

- ↑ Brooks, Katherine (February 14, 2013). "Isleworth Mona Lisa Declared Authentic By Swiss-Based Art Foundation And More Art News (PHOTO)". Huffington Post. Retrieved April 19, 2013.

- ↑ "Fresh proof found for the other, 'original' 'Mona Lisa'". Archived from the original on February 16, 2013. Retrieved April 20, 2013.

- ↑ John F. Asmus, "Computer Studies of the Isleworth and Louvre Mona Lisas", in T. Russell Hsing and Andrew G. Tescher, Selected Papers on Visual Communication: Technology and Applications (SPIE Optical Engineering Press, 1990), pp. 652-656; reprinted from Optical Engineering, Vol. 28(7) (July 1989), pp. 800-804.

- ↑ Evans, Robert (13 February 2013). "New proof said found for "original" Mona Lisa". Reuters.

- 1 2 Chris Pritchard, "France said 'non'–so Britain finds another Mona Lisa", The Sydney Morning Herald (October 22, 1972), p. 62.

- ↑ "The World", The New York Times (October 22, 1972), p. E-4.

- ↑ Raymond R. Coffey, "Does Mona Lisa Know", Charleston Daily Mail (October 17, 1972), p. 9A, via the Chicago Daily News.

- ↑ Loadstar's Lair (2007). "Mona Lisa". Loadstar's Lair. Retrieved September 15, 2007.

- ↑ "Works on the Fine Arts", Somerset House Gazette and Literary Museum, No. XLII (London, July 24, 1824), p. 242.

- ↑ Charlotte Higgins (2006-09-23). "Unveiled: early copy that reveals Mona Lisa as her creator intended". The Guardian Unlimited. London. Retrieved September 15, 2007.

- ↑ "Mona Lisas: compare Leonardo with his pupil – interactive" at guardian.co.uk.

- ↑ Brown, Mark (2012-02-01). "The real Mona Lisa? Prado museum finds Leonardo da Vinci pupil's take". The Guardian. London.

- ↑ Jeanna Bryner (5 May 2014). "Did Da Vinci create a 3-D 'Mona Lisa'?". LiveScience.

- ↑ Brooks, K. R. (1 January 2017). "Depth Perception and the History of Three-Dimensional Art: Who Produced the First Stereoscopic Images?". i-Perception. 8 (1): 204166951668011. doi:10.1177/2041669516680114. PMC 5298491. PMID 28203349.

Bibliography

- Kemp, Martin (2006). Leonardo da Vinci: the marvellous works of nature and man. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-280725-0. Retrieved 10 October 2010.