Nimbus 1 satellite image of Typhoon Sally (Aring) on September 10 shortly after its landfall in South China | |

| Meteorological history | |

|---|---|

| Formed | September 3, 1964 |

| Dissipated | September 11, 1964 |

| Violent typhoon | |

| 10-minute sustained (JMA) | |

| Highest winds | 220 km/h (140 mph) |

| Lowest pressure | 895 hPa (mbar); 26.43 inHg |

| Category 5-equivalent super typhoon | |

| 1-minute sustained (SSHWS/JTWC) | |

| Highest winds | 315 km/h (195 mph) |

| Lowest pressure | 894 hPa (mbar); 26.40 inHg |

| Overall effects | |

| Fatalities | 10 as a tropical cyclone, ≥211 from remnants |

| Damage | $1.37 million |

| Areas affected | Marianas Islands, Luzon, Batanes Islands, Babuyan Islands, Taiwan, Hong Kong, South Korea |

| IBTrACS | |

Part of the 1964 Pacific typhoon season | |

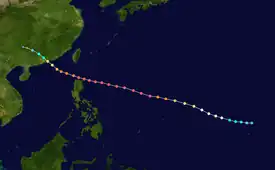

Typhoon Sally, known in the Philippines as Typhoon Aring,[1] was a powerful tropical cyclone that brought widespread impacts during its week-long trek across the western Pacific in September 1964. The strongest tropical cyclone of the 1964 Pacific typhoon season and one of the most intense tropical cyclones on record, and among the strongest typhoons ever recorded, with one-minute maximum sustained winds of 315 km/h (196 mph) as estimated by the Joint Typhoon Warning Center. Sally first became a tropical cyclone near the Marshall Islands on September 3, organizing into a tropical depression and then a tropical storm later that day. On September 4, Sally intensified into a typhoon and struck southern Guam the next day. Widespread agricultural damage occurred in the island's southern regions, with the banana crop suffering the costliest losses; the damage toll from crops and property exceeded $115,000. Sally continued to intensify on its west-northwestward trek, and reached its peak strength on September 7 over the Philippine Sea.

Sally's winds lessened thereafter as it brushed the northern Philippines, buffeting areas north of Manila with strong winds and heavy rain and causing serious damage. A person drowned from the typhoon's onslaught, while the naval station at San Vicente and the adjoining village sustained an estimated $500,000 in damage. After crossing the South China Sea, Sally made landfall on the South China coast east of Hong Kong on September 10. Due to fears of a repeat of Typhoon Ruby, which struck the region less than a week prior, 10,000 people were evacuated ahead of the storm. Sally produced wind gusts as strong as 154 km/h (96 mph) and dropped torrential rain that damaged homes and crops and induced one landslide that killed nine people. However, the overall impacts in Hong Kong were less than forecast. Sally weakened as it moved into inland China and dissipated on September 11. The remnants of Sally moved northeast and contributed to severe flooding around Seoul, South Korea, leaving 211 people dead or missing and 317 people injured, though 206 people remain unaccounted for. Over 36,000 people were left homeless as over 9,000 homes were either destroyed or flooded, resulting in $750,000 in property damage. The floods were the region's most significant in two decades.

Meteorological history

Tropical storm (39–73 mph, 63–118 km/h)

Category 1 (74–95 mph, 119–153 km/h)

Category 2 (96–110 mph, 154–177 km/h)

Category 3 (111–129 mph, 178–208 km/h)

Category 4 (130–156 mph, 209–251 km/h)

Category 5 (≥157 mph, ≥252 km/h)

Unknown

The origins of Sally can be traced to the interaction of a trough of low pressure with a westward-propagating tropical wave. This led to the development of a vortex over the Marshall Islands on September 2.[2] The next day, observations from ships in the region indicated that the system organized into a tropical depression approximately 240 km (150 mi) southwest of Eniwetok Atoll. Aircraft reconnaissance investigating the nascent cyclone later that day determined that Sally reached tropical storm strength while located roughly 320 km (200 mi) northeast of Chuuk State.[3] During this time, Sally took a west-northwest course that would continue for the remainder of its duration.[4] The storm intensified into a typhoon early on September 4.[4] The next day, the center of Sally moved across southern Guam with a forward speed of 37 km/h (23 mph); one-minute maximum sustained winds near the center were estimated by the Joint Typhoon Warning Center (JTWC) to have reached 155 km/h (96 mph) during its passage of Guam.[3][5]

Sally strengthened further as it traversed the Philippine Sea, and at 06:00 UTC on September 7, the JTWC analyzed Sally's one-minute sustained winds to have reached 315 km/h (196 mph); surface winds as fast as 370 km/h (230 mph) were estimated by aircraft reconnaissance probing the typhoon.[4][2] The Japan Meteorological Agency (JMA) estimated that Sally's central barometric pressure decreased to 895 hPa (mbar; 26.43 inHg).[4] This made Sally the strongest typhoon of the 1964 Pacific typhoon season as measured by both wind speed (tied with Opal) and central pressure.[3] These winds were also among the fastest ever analyzed for a tropical cyclone globally.[6] The center of Sally then moved near the northern Philippines, passing 40 km (25 mi) north of Aparri on September 9.[7] The JTWC estimated that Sally's one-minute sustained winds decreased during this period, and continued to diminish further as the typhoon tracked across the South China Sea.[4] At 15:00 UTC on September 10, Sally made landfall on the People's Republic of China east of Hong Kong with one-minute sustained winds of 155 km/h (96 mph). After moving inland, the system rapidly weakened, degenerating into a tropical storm later on September 10 and losing its identity as a tropical cyclone the following day over South China.[3][2][4] The remnants of Sally continued towards South Korea and Japan before they were last noted on September 16 over southern Kamchatka.[3]

Preparations and impact

Guam and the Philippines

On September 4, Sally was forecast by the JTWC to bring heavy surf and sustained winds of 75–85 km/h (47–53 mph) to Guam, accompanied by higher gusts.[8] Sally was ultimately stronger and closer to Guam than forecast,[9] crossing over southern Guam as a developing typhoon on September 5 and producing damaging winds.[5] While the highest observed wind gust reached 100 km/h (62 mph) at Andersen Air Force Base, higher gusts up to 130 km/h (81 mph) were estimated to have buffeted Guam. Gale-force winds lasted for eight hours. A maximum 24-hour rainfall total of 53 mm (2.1 in) accompanied the storm.[5] Over 1,000 people sought refuge at the College of Guam, and others took shelter in other sturdy buildings.[10] Numerous trees were downed and homes were unroofed by the typhoon.[5] Downed trees and other debris blocked roads, rendering them impassable.[11]: 12 The island's southern districts sustained the heaviest impacts from Sally; 18 structures in those areas were damaged, with the impacts most evident to their roofs.[11]: 1 The majority of the monetary losses caused by Sally on the island was sustained by crops: agricultural damage was estimated at $105,440, with $92,398 sustained by the banana crop.[5][12] Damage to residential and commercial buildings was estimated at $9,680, resulting in a total damage toll of about $115,000, mostly were to farm crops.[12] Storm surge along Talofofo Bay led to coastal inundation;[5] eight homes suffered roof damage there.[11]: 1 Damage was also documented in Agat, Inarajan, Merizo, and Umatac. Power outages occurred in those villages in addition to Talofofo and Santa Rita. Sally's impacts in Guam were negligible outside of the southern regions of the island,[11]: 12 and in total there were no casualties.[13]

Sally was one of the strongest to approach the Philippines on record.[14] The west-northwestward trajectory of Sally threatened the northern Philippines, leading to the issuance of warnings for the region by the Philippine Weather Bureau on September 7.[15] Typhoon signal no. 2, signifying winds up to 114 km/h (71 mph) within 24 hours, was issued for the Batanes Islands.[14] The storm brought strong winds and heavy rains to areas north of Manila,[7] resulting in substantial crop and property damage.[16] The United States Agency for International Development described Sally as having done "considerable damage" in northern Luzon, but could not assess the total number of casualties.[17] The naval station at San Vicente and the adjoining village sustained an estimated $500,000 in damage; one person drowned and two thousand others were left in need of food and clothing.[18]

Hong Kong and Taiwan

The outer reaches of Sally brought high winds to southern Taiwan but were inconsequential.[19] Following Typhoon Ruby's impacts in Hong Kong earlier in September, 3,400 workers were enlisted to clear the colony's drainage systems in preparation for Sally.[20] While the center of the storm was forecast to miss Hong Kong, Sally's peripheral winds were expected to be comparable to Ruby's.[21] A spokesperson for the Royal Observatory in Hong Kong called Sally "the biggest [typhoon] in living memory" while the storm was centered 275 km (171 mi) to the southeast.[22][23] The Hong Kong government noted that cranes, fences, scaffolding, and signboards loosened in Ruby's passage became hazardous with Sally's potential impacts.[24] Ships were brought to protected moorings at the harbor in Hong Kong after the issuance of the first tropical cyclone signals for Sally's approach, leaving the harbor devoid of any vessels; two ships evacuated to open sea to ride out the storm there.[20][25] Businesses closed and bus and ferry service saw suspensions.[22] Some airlines also canceled their fights.[22]: 7 Over 10,000 people were evacuated out of vulnerable areas.[26] Radio broadcasts called upon residents to head home and remain home while Sally passed. Riot police were deployed for crowd control as people began to flee Hong Kong's islands for the mainland en masse. The Hong Kong Red Cross started a blood donation drive in downtown Hong Kong, offering free beer and cigarettes to donors. Sixteen first aid centers were also established throughout Hong Kong.[22]

Sally was the fourth typhoon to impact the Hong Kong area in 1964,[27] though its effects were less severe than initially feared.[28] Thirty people were injured in Hong Kong.[29] The outer extents of Sally began affecting the territory before the storm's closest approach, with the outer winds triggering landslides and depositing trees, glass, and other debris on streets. One person sustained a fractured skull after being struck by a falling iron rod.[22]: 7 During its closest approach, the center of Sally was 55 km (34 mi) northeast of Hong Kong.[30] The Royal Observatory escalated their warnings up to tropical cyclone signal no. 7 and recorded a peak gust of 104 km/h (65 mph) at their headquarters.[31][30] The strongest gust measured in Hong Kong reached 154 km/h (96 mph) as registered at Tate's Cairn. Gusts reached 107 km/h (66 mph) at Kai Tak Airport.[32] Sally produced up to 354.4 mm (13.95 in) of rain in Hong Kong with over 175 mm (6.9 in) falling in 12 hours;[32][26] landslides triggered by these rains killed 9 people and injured 24, in addition to causing the collapse of houses.[30] Other landslides marooned people in their homes and blocked streets.[33][28] Severe flooding occurred throughout Hong Kong.[29] Cattle and crop industries were impacted by the storm, though the overall damage was minimized by Typhoon Ruby's agricultural impacts less than week prior. A few hundred chickens were killed by Sally. At Tai Po, the storm caused tides to rise 1.1 m (3.6 ft) above astronomical tide. Eight boats were damaged at Ko Lau Wan and Sha Tau Kok; additional locales in Hong Kong also reported damage to fishing craft, leading to the colonial government granting HK$10,031 in repairs.[32]

South Korea

The remnants of Sally produced the heaviest rainfall in the Seoul area in 22 years, with 125–200 mm (4.9–7.9 in) of rain falling in the area in two hours on the morning of September 13.[3][34] At least 211 people were killed and 317 people were injured according to local police; another 206 people were unaccounted for.[35] The high death toll was compounded by the storm's passage at night when most people were asleep.[36] The combination of flash floods and landslides in central South Korea destroyed and flooded 9,152 homes, displacing 36,665 people. Bridges, highways, railroads, and rice paddies were seriously damaged.[37] Total property damage amounted to $750,000.[38] Hardest-hit was Gyeonggi Province, where 72 people died and 115 people went missing.[36] There were 26 confirmed fatalities in Gangwon Province.[39] In Seoul, there were at least 70 fatalities.[39] Almost 2,800 houses were destroyed or inundated around the city.[39] Seoul's power and telephone services were also hampered by the storm.[36] Railways between Seoul and eastern South Korea were cut off by landslides and washouts.[39] A village north of Seoul was completely flooded after a river overflowed its banks; all 96 inhabitants of the village were declared missing, though 10 bodies were later recovered. Fifty homes were buried by a landslide 55 km (34 mi) northeast of Seoul, killing 21 people.[36] The State Council of South Korea convened in an emergency session on September 14 in response to the floods.[34] Park Chung-hee, the President of South Korea, initiated "emergency relief measures" for those affected by the storms.[36] Food and bedding were provisioned by the Korean government through an assistance program for affected areas.[38] Chung-hee also ordered soldiers deployed in Seoul to handle rescue operations; they were also joined by soldiers from the United States Army.[40][39] Helicopters from the U.S. Army evacuated at least 50 flood-stricken people from the suburbs of Seoul.[36]

See also

- Typhoon Mangkhut (2018)

- Typhoon Viola (1969)

- Typhoon Rita (1953)

- Typhoon Kent (1995)

- Typhoon Sally (1996) – a typhoon with the same name that had an identical track and intensity 32 years later.

References

- ↑ "Annual Report of the Weather Bureau, FY 1964–1965". Manila, Philippines: Philippines Weather Bureau. 1965.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - 1 2 3 Cassidy, Richard M., ed. (February 15, 1964). Annual Typhoon Report, 1964 (PDF) (Report). Annual Typhoon Report. Guam, Mariana Islands: Fleet Weather Central/Joint Typhoon Warning Center. Retrieved June 12, 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Climatological Data: National Summary (Annual 1964)" (PDF). Climatological Data. Asheville, North Carolina: United States Weather Bureau. 15 (13). 1965. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 13, 2020. Retrieved June 12, 2020 – via National Centers for Environmental Information.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "1964 Super Typhoon SALLY (1964247N09159)". IBTrACS - International Best Track Archive for Climate Stewardship. Asheville, North Carolina: University of North Carolina–Asheville. 2018. Retrieved June 28, 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Weir, Robert C. (October 25, 1983). Tropical Cyclones Affecting Guam (1671–1980) (PDF) (Report). San Francisco, California: Joint Typhoon Warning Center. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 5, 2020. Retrieved June 12, 2020.

- ↑ "Typhoon Haiyan: how does it compare with other tropical cyclones?". The Guardian. Guardian News and Media Limited. November 8, 2013. Retrieved July 4, 2020.

- 1 2 "Typhoon Blows By Philippines". Santa Maria Times. Santa Maria, California. United Press International. September 9, 1964. p. 23. Retrieved July 3, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Typhoon Nearing Guam". Guam Daily News. Vol. 19, no. 216. Hagåtña, Guam. September 5, 1964. p. 2. Retrieved July 3, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Unforgotten Lesson". Guam Daily News. Vol. 19, no. 217. Hagåtña, Guam. September 7, 1964. p. 2. Retrieved July 3, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Guam Is Battered By Typhoon Sally". Honolulu Star-Bulletin. Vol. 53, no. 249. Honolulu, Hawaii. September 5, 1964. p. 1. Retrieved June 29, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- 1 2 3 4 "Typhoon Sally Damages 18 Houses Here". Guam Daily News. Vol. 19, no. 217. Hagåtña, Guam. September 7, 1964. pp. 1, 12. Retrieved July 3, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- 1 2 "Over $115-Gs Damage By 'Sally' Here". Guam Daily News. Vol. 19, no. 224. Hagåtña, Guam. September 15, 1964. p. 12. Retrieved July 3, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Typhoon Sally Does Light Damage". The Sacramento Bee. Vol. 215, no. 34928. Sacramento, California. September 6, 1964. p. A16. Retrieved July 3, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- 1 2 "Typhoon Moves On North Philippines". The Honolulu Advertiser. No. 54511. Honolulu, Hawaii. United Press International. September 8, 1964. p. A11. Retrieved July 3, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Storm Threatens The Philippines". Alexandria Daily Town Talk. Vol. 82, no. 150. Alexandria, Louisiana. United Press International. September 7, 1964. p. 33. Retrieved July 3, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Huge Typhoon Heads For Hong Kong". Los Angeles Times. Vol. 83. Los Angeles, California. United Press International. September 10, 1964. p. 23. Retrieved July 3, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ Henderson, Faye (1980). "Tropical Cyclone Disasters in the Philippines" (PDF). Washington, D.C.: United States Agency for International Development. p. 15. Retrieved July 3, 2020.

- ↑ "Formosa Escapes Typhoon Tilda's Fury". Racine Journal-Times. Vol. 108, no. 219. Racine, Wisconsin. Associated Press. September 16, 1964. p. 5E. Retrieved September 4, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Typhoon Lashes Philippines". The Edmonton Journal. Edmonton, Alberta. Associated Press. p. 2. Retrieved July 3, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- 1 2 "Hong Kong Eyes Sally". Victoria Daily Times. No. 78. Victoria, British Columbia. United Press International. p. 19. Retrieved July 3, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Sally Smashes Into Hong Kong". The Windsor Star. Vol. 93, no. 8. Windsor, Ontario. United Press International. September 10, 1964. p. 1. Retrieved July 3, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Huge Typhoon Sets Hong Kong Chinese Panic". Corsicana Daily Sun. Vol. 69, no. 81. Corsicana, Texas. Associated Press. September 10, 1964. pp. 1, 7. Retrieved July 3, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Hong Kong Buttons Up". The Miami Herald. No. 281. Miami, Florida. Associated Press. September 10, 1964. p. 2A. Retrieved July 3, 2020 – via newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Hong Kong Girds For 2nd Typhoon". The Detroit Daily Press. Vol. 1, no. 49. Detroit, Michigan. Reuters. September 9, 1964. p. 18. Retrieved July 3, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Typhoon Sally Nears Hong Kong". The Capital Times. Vol. 94, no. 77. Madison, WIsconsin. United Press International. September 10, 1964. p. 3. Retrieved July 3, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- 1 2 "Slide Triggered By Typhoon Kills Six In Hong Kong". Poughkeepsie Journal. Vol. 180, no. 32. Poughkeepsie, New York. Associated Press. September 11, 1964. p. 10. Retrieved July 4, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Hong Kong Set For Sideswipe Of 4th Typhoon". The Philadelphia Inquirer. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. United Press International. September 10, 1964. p. 3. Retrieved July 3, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- 1 2 Essoyan, Roy (September 11, 1964). "Typhoon Sally Hits Hong Kong". The Oregon Statesman. No. 168. Salem, Oregon. Associated Press. p. 26. Retrieved July 4, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- 1 2 "Typhoon Rains Swamp Hong Kong". Stevens Point Daily Journal. Stevens Point, Wisconsin. Associated Press. September 11, 1964. p. 1. Retrieved July 4, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- 1 2 3 Woon-Pui, Kwong (April 1974). "Tropical Cyclone Rainfall In Hong Kong" (PDF). Hong Kong, China: Hong Kong Observatory. Retrieved July 3, 2020.

- ↑ Pui-yin, Ho (2003). "A Review of Natural Disasters of the Past". Weathering the Storm: Hong Kong Observatory and Social Development (PDF). Hong Kong, China: Hong Kong University Press. ISBN 9622097014. Retrieved June 13, 2020.

- 1 2 3 Shing, Pun Kwok (May 1966). A Survey of the Climatological Phenomena of Typhoons of Western N. Pacific Ocean and the South China Sea With Special Preference to Hong Kong (M.A.). University of Hong Kong.

- ↑ "Sally Lives Up To Fickle Typhoon Nature Today". The Daily Free Press. No. 119. Nanaimo, British Columbia. Associated Press. September 11, 1964. p. 5. Retrieved July 4, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- 1 2 "Korea Flood Toll Grows". Evening Journal. Vol. 32, no. 217. Wilmington, Delaware. Associated Press. September 14, 1964. p. 2. Retrieved July 4, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Korea Storm Toll May Reach 400". Independent. Vol. 27, no. 16. Long Beach, California. Associated Press. September 16, 1964. p. A5. Retrieved July 4, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "403 Die, Hundreds Hurt In Fierece Korea Floods". The Boston Globe. Vol. 186, no. 76. Boston, Massachusetts. United Press International. September 14, 1964. p. 8. Retrieved July 4, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "190 Killed In South Korea Floods, Landslides". Sun-Democrat. Vol. 87, no. 221. Paducah, Kentucky. Associated Press. September 14, 1964. p. 9. Retrieved July 4, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- 1 2 "Storm Kills 190". The News and Observer. Vol. 199, no. 77. Raleigh, North Carolina. United Press International. September 15, 1964. p. 2. Retrieved July 4, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "250 Reported Killed In Korea Floods". The Knoxville Journal. Vol. 220, no. 88. Knoxville, Kentucky. CTPS. September 14, 1964. p. A7. Retrieved July 4, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Korea Slides; Floods Kill 86". The Morning Call. No. 24177. Allentown, Pennsylvania. Associated Press. September 14, 1961. p. 3. Retrieved July 4, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.