| 6th Marine Division | |

|---|---|

6th Marine Division insignia | |

| Active | 7 September 1944 – 1 April 1946 |

| Country | |

| Branch | |

| Type | Infantry |

| Role | Locate, close with, and destroy the enemy by fire and maneuver |

| Nickname(s) | The Striking Sixth[1] or New Breed[2] |

| Engagements | World War II |

| Decorations | Presidential Unit Citation |

| Commanders | |

| Notable commanders | Lemuel C. Shepherd, Jr. |

The 6th Marine Division was a United States Marine Corps World War II infantry division formed in September 1944. During the invasion of Okinawa it saw combat at Yae-Take and Sugar Loaf Hill and was awarded a Presidential Unit Citation. The 6th Division had also prepared for the invasion of Japan before the war ended. After the war it served in Tsingtao, China, where the division was disbanded on April 1, 1946, being the only Marine division to be formed and disbanded overseas and never set foot in the United States.[4]

World War II

Formation on the Solomon Islands

The 6th Marine Division was activated on Guadalcanal in the southern Solomon Islands on September 7, 1944.[4][5] The 6th Division was formed from three infantry regiments, the 4th, 22nd, and 29th Marines and other units such as engineer, medical, pioneer, motor transport, tank, headquarters, and service battalions.[4] The core cadre around which the division was formed was the former 1st Provisional Marine Brigade which included the 4th and 22nd Marine Regiments, plus their supporting artillery battalions; these artillery battalions were later consolidated into the 15th Marine Regiment.[4]

The Battle of Guam ended in August 1944 and the 1st Provisional Marine Brigade was called to Guadalcanal along with the 1st Battalion, 29th Marines, which had served with the 2nd Marine Division in the Battle of Saipan on the Mariana Islands. With a core of all these veterans incorporated into the new division, the 6th was not considered "green" despite being a new formation; most of the men were veterans of at least one campaign and many were serving a second combat tour,[6] half the forces in the three Infantry Regiments were all veterans,[1] and some units even consisted of 70% veterans.[7] The 2nd and 3rd Battalions, 29th Marines, disembarked from the United States on 1 August 1944, and landed on Guadalcanal on 7 September 1944 to further augment the division.[4] The now fully manned 6th Division underwent "rugged" training on Guadalcanal between October and January[6] before it shipped 6,000 miles to land as part of the III Amphibious Corps on Okinawa on 1 April 1945.[4]

Okinawa

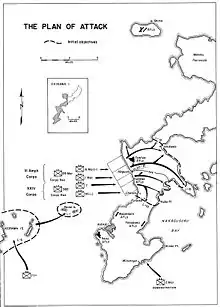

The division's initial objectives in the amphibious landing were the capture of Yontan Airfield and protection of the left (north) flank.[8] Despite a Japanese battalion in their zone[9] the division met only light resistance. By the third day, the division was approaching Iskhikawa, twelve days ahead of schedule.[10] By 14 April, the division had swept all through the northern Ishikawa Isthmus, 55 miles from the original landings.[11] The division's rapid advance continued until eventually they encountered prepared and dug-in defenders at Yae-Take, where the majority of the Udo Force was entrenched. The Udo Force, or Kunigami Detachment, under Colonel Takehiko Udo was built around the 2nd Infantry Unit of the 44th Independent Mixed Brigade—reinforced by having absorbed both former sea-raiding suicide squadrons and remnants of the Battalion earlier destroyed by the 6th—was responsible for defense of the Motobu Peninsula and Ie Shima.[12] The 6th Division's drive captured most of northern Okinawa and the Division won praise for its fast campaign – Brigadier General Oliver P. Smith wrote: "The campaign in the north should dispel the belief held by some that Marines are beach-bound and are not capable of rapid movement."[11]

After heavy fighting in the south, the division was ordered to replace the Army 27th Infantry Division on the western flank. The 6th division advanced south to partake in the assault against the strong Japanese defense line, called the Shuri Line, that had been constructed across the southern coastline. The Shuri Line was located in hills that were honeycombed with caves and passages, and the Marines had to traverse the hills to cross the line. The division was ordered to capture the Sugar Loaf Hill Complex, 3 hills which formed the western anchor of the Shuri Line defense.[13][14] The Marines that had assaulted the line were attacked by heavy Japanese mortar and artillery fire, which made it more difficult to secure the line.[4] After a week of fighting, the hill had been taken.[13]

After Sugarloaf the Division advanced through Naha, conducted a shore-to-shore amphibious assault on, and subsequent 10-day battle to capture, the Oroku peninsula[15] (defended by Admiral Ōta's forces), and partook in mop-up operations in the south. The battle on Okinawa ended on 21 June 1945. The Sixth division was credited with over 23,839 enemy soldiers killed or captured,[16] and with helping to capture 2⁄3 of the island,[17] but at the cost of heavy casualties,[18] including 576 casualties on one day (May 16) alone,[19] a day described as the "bitterest" fighting of the Okinawa campaign where "the regiments had attacked with all the effort at their command and had been unsuccessful".[20]

For its actions at Okinawa, the 6th Marine Division (and reinforcing units) earned a Presidential Unit Citation. The citation reads:

For extraordinary heroism in action against enemy Japanese forces during the assault and capture of Okinawa, April 1 to June 21, 1945. Seizing Yontan Airfield in its initial operation, the SIXTH Marine Division, Reinforced, smashed through organized resistance to capture Ishikawa Isthmus, the town of Nago and heavily fortified Motobu Peninsula in 13 days. Later committed to the southern front, units of the Division withstood overwhelming artillery and mortar barrages, repulsed furious counterattacks and staunchly pushed over the rocky terrain to reduce almost impregnable defenses and capture Sugar Loaf Hill. Turning southeast, they took the capital city of Naha and executed surprise shore-to-shore landings on Oroku Peninsula, securing the area with its prized Naha Airfield and Harbor after nine days of fierce fighting. Reentering the lines in the south, SIXTH Division Marines sought out enemy forces entrenched in a series of rocky ridges extending to the southern tip of the island, advancing relentlessly and rendering decisive support until the last remnants of enemy opposition were exterminated and the island secured. By their valor and tenacity, the officers and men of the SIXTH Marine Division, Reinforced contributed materially to the conquest of Okinawa, and their gallantry in overcoming a fanatic enemy in the face of extraordinary danger and difficulty adds new luster to Marine Corps history, and to the traditions of the United States Naval Service.

— Secretary of the Navy James Forrestal for the President[21]

During the war, the 6th Marine Division had two Seabee Battalions posted to it. The 53rd Naval Construction Battalion (NCB) was a component of the 1st Provisional Marine Brigade. Later the 58th NCB replaced them for the invasion of Okinawa. (see: Seabees)

Guam and China

In July 1945, the 6th division was withdrawn from Okinawa to the island of Guam to prepare for Operation Coronet, the planned invasion of Honshū, Japan that was supposed to occur in March 1946 but the Japanese surrendered in August 1945. While the 4th Marines were sent for brief occupation duty in Japan,[22] the rest of the 6th spent September in Guam preparing for duty in China.[23]

The division arrived in Tsingtao, China on 11 October 1945[23] where it remained until it was disbanded on April 1, 1946,[24][25][26] being replaced by the 3d Marine Brigade.[27] In its time at Tsingtao the division not only accepted the surrender of local Japanese forces (on October 25[24][25]) but also oversaw their subsequent repatriation to Japan; prevented the communists from attacking the surrendered Japanese forces and dissuaded communist forces from advancing on the city,[28] restored and maintained order,[29] and came to be seen as the protector of minority groups in the former German concession.[25]

Command structure

The 6th Division had two commanders during its short existence:[26]

- Major General Lemuel C. Shepherd, Jr., 7 September 1944 – 24 December 1945

- Major General Archie F. Howard, 24 December 1945 – 1 April 1946

Assistant Division Commander

- Brigadier General William T. Clement, November 1944 – 1 April 1946[26][30]

Chief of Staff

- Colonel John T. Walker, 7 September 1944 – 16 November 1944

- Colonel John C. McQueen, 17 November 1944 – 16 February 1946

- Colonel Harry E. Dunkelberger, 17 February 1946 – 1 April 1946

Personnel Officer (G-1)

- Major Addison B. Overstreet, 7 September 1944 – 22 July 1945

- Colonel Karl K. Louther, 23 July 1945 – 17 November 1945

- Lieutenant Colonel Frederick Belton, 18 November 1945 – 31 March 1946

Intelligence Officer (G-2)

- Lieutenant Colonel August Larson, 7 September 1944 – 30 September 1944

- Major William R. Watson, Jr., 1 October 1944 – 9 November 1944

- Lieutenant Colonel Thomas E. Williams, 10 November 1944 – 16 February 1946

- Lieutenant Colonel Carl V. Larsen, 17 February – 31 March 1946

Operations Officer (G-3)

- Lieutenant Colonel Thomas A. Culhane, Jr., 7 September 1944 – 10 November 1944

- Lieutenant Colonel Victor H. Krulak, 11 November 1944 – 26 October 1945

- Lieutenant Colonel Wayne H. Adams, 27 October 1945 – 31 December 1945

- Lieutenant Colonel George W. Killen, 1 January 1946 – 31 March 1946

Logistics Officer (G-4)

- Lieutenant Colonel August Larson, 1 October 1944 – 17 May 1945

- Lieutenant Colonel Wayne H. Adams, 18 May 1945 – 31 December 1945

- Lieutenant Colonel Samuel R. Shaw, 1 January 1946 – 31 March 1946

Subordinate units

- Colonel Alan Shapley, 7 September 1944 – 3 July 1945

- Lieutenant Colonel Fred D. Beans, 4 July 1945 – 28 January 1946

- Colonel Wilburt S. Brown, 23 October 1944 – 17 November 1944

- Colonel Robert B. Luckey, 18 November 1944 – 15 March 1946

- Colonel Merlin F. Schneider, 7 September 1944 – 16 May 1945

- Colonel Harold C. Roberts, 17 May 1945 – 18 June 1945 (KIA)

- Lieutenant Colonel August Larson, 19 June 1945 – 24 June 1945

- Colonel John D. Blanchard, 25 June 1945 – 31 March 1946

- Colonel Victor Bleasdale, 7 September 1944 – 14 April 1945

- Colonel William J. Whaling, 15 April 1945 – 31 March 1946

6th Tank Battalion

- Major Harry T. Milne, 29 September 1944 – 16 October 1944

- Lieutenant Colonel Robert L. Denig Jr., 17 October 1944 – 26 March 1946

Campaign and award streamers

| Streamer | Award | Additional info |

|---|---|---|

| Presidential Unit Citation Streamer | Okinawa, April 1 — June 30, 1945 | |

| China Service Medal (Extended) | Oct. 11, 1945 — March 26, 1946 | |

| Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal[31] | ||

| World War II Victory Medal | ||

Medal of Honor recipients

The Medal of Honor was awarded to five Marines and one Navy corpsman assigned to the 6th Marine Division during World War II:[4]

- Richard E. Bush

- Henry A. Courtney Jr., USMCR (posthumous)

- James L. Day

- Harold Gonsalves (posthumous)

- Fred F. Lester, USN (posthumous)

- Robert M. McTureous Jr. (posthumous)

See also

Notes

- 1 2 Hallis (2007), p. 15

- ↑ Sloan (2008), p. 398

- ↑ The 15th Marines was an artillery regiment.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Sixth Marine Division official website

- ↑ Carlton (1946), p. 1 & Rottman (2002) p. 140.

- 1 2 Frank & Shaw (1968), p. 88

- ↑ Sloan (2008), p. 147

- ↑ Carleton (1946), p. 4; Frank & Shaw (1968), p. 68

- ↑ Frank & Shaw (1968), p. 120

- ↑ Frank & Shaw (1968), p. 128

- 1 2 Brigadier General Oliver P. Smith's Personal Narrative, p. 82, quoted in Frank & Shaw (1968), p. 155

- ↑ Frank & Shaw (1968), pp. 49–50, 53, 55

- 1 2 Wukovits (2006)

- ↑ Sugar-Loaf the Gateway to Naha

- ↑ Frank & Shaw (1968), pp. 300–324

- ↑ sources vary: 20,532 killed and 3,307 taken prisoner according to Carlton (1946), p. 123, or 23,000 killed and over 3,500 captured according to Stockman, p. 16

- ↑ Stockman, p.16

- ↑ sources differ as to how many: The official report lists 8,222 casualties, of which 1,622 were killed. The official Sixth Division Website states nearly 1,700 killed or died of wounds and more than 7,400 wounded. Stockman (p. 16) says 8,222 killed and wounded. Frank & Shaw (1968) in appendix M gives 9,105 killed, missing, or wounded. Carlton (1946), in the Appendix Charts has 1,337 dead, 5,706 wounded and nearly 11,000 total casualties, while Wukovits and Frank & Shaw (1968), (both in turn referencing the 6thMarDiv SAR, Ph III, p. 9), give 2,662 killed or wounded at Sugar Loaf Hill alone with another 1,289 having to be evacuated from there due to exhaustion or battle fatigue

- ↑ Carlton (1946), Appendix Chart No. 1

- ↑ 6th MarDiv SAR, Ph III, p.9 quoted in Frank & Shaw (1968), p. 250

- ↑ Frank & Shaw (1968), p. 886 (appendix N)

- ↑ They rejoined the division in China in January, see Frank & Shaw (1968), p. 490

- 1 2 Stockman, p. 18

- 1 2 Nofi (1997), p. 79

- 1 2 3 Stockman, p. 19

- 1 2 3 Frank & Shaw (1968), p. 873 (Appendix L)

- ↑ Frank & Shaw (1968), p. 599

- ↑ Stockman, pp. 18–19; Shaw (1968), pp. 6–13; & Frank & Shaw (1968), p. 564

- ↑ Frank & Shaw (1968), p. 565

- ↑ Carleton (1946), p.3

- ↑ Members of the Division HQ during Okinawa are eligible for a bronze campaign star.

References

- Bibliography

- Frank, Benis M.; Shaw Jr., Henry I. (1968), Victory and occupation (PDF), History of U.S. Marine Corps Operation in World War II, vol. V, Washington, D.C.: Historical Branch, G-3 Division, Headquarters, U.S. Marine Corps, p. 886, archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-07-14, retrieved 2014-07-04, transcription also available here

- Carlton, Philips D. (1946). The conquest of Okinawa: an account of the Sixth Marine Division. Washington, D.C.: Historical Division, Headquarters, U.S. Marine Corps.

- Hallis, James (1 Sep 2007). Killing Ground on Okinawa: The Battle for Sugar Loaf Hill. Naval Institute Press. ISBN 9781591143567.

- Nofi, Albert (1997). The Marine Corps Book of Lists (Illustrated ed.). Da Capo Press. p. 79. ISBN 9780938289890.

- Rottman, Gordon L. (2002). U.S. Marine Corps World War II Order of Battle: Ground and Air Units in the Pacific War. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-313-31906-5.

- Shaw Jr., Henry I (1968) [1960]. The United States Marines in North China 1945–1949 (PDF). Marine Corps Historical Reference Pamphlet (Revised 1962 ed.). Washington D.C.: Historical Branch, G-3 Division, Headquarters, U.S. Marine Corps. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-07-14. Retrieved 2014-07-06.

- Sloan, Bill (14 Oct 2008). The Ultimate Battle: Okinawa 1945—The Last Epic Struggle of World War II. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 9780743292474.

- Stockman, James R. Sixth Marine Division (PDF). Historical Division, Headquarters, U.S. Marine Corps. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 5 July 2013.

- Wukovits, John. "Survival at Sugar Loaf". WWII History Magazine (May 2006). Available at The Military and Wars website, Something about everything military series, Okinawa: Sugar Loaf Hill webpage

- Web

- Sixth Marine Division Association's website

- Johnmeyer, Hillard E. "Okinawa: Sugar Loaf Hill". The Military and Wars. Something about everything military, From the Revolution to Nuclear Subs. Archived from the original on 27 September 2011. Retrieved 5 July 2013.

Further reading

- Appleman, Roy Edgar; Burns, James M.; Gugeler, Russel A.; Stevens, John (1948). Okinawa: The Last Battle. Washington DC: United States Army Center of Military History. ISBN 1-4102-2206-3. Archived from the original on 2010-11-08. Retrieved 2014-07-13. full text online

- Cass, Bevan G., ed. (1987) [1948]. History of the Sixth Marine Division. 1st (1948) Edition published by Infantry Journal Press, Washington, DC. 1987 reprint published by Battery Press, Nashville, TN

- Fisch Jr., Arnold G. (2004). Ryukyus. World War II Campaign Brochures. Washington D.C.: United States Army Center of Military History. ISBN 0-16-048032-9. CMH Pub 72-35. Archived from the original on 2012-01-05. Retrieved 2014-07-13.

- Huber, Thomas M. (May 1990). "Japan's Battle of Okinawa, April–June 1945". Leavenworth Papers. United States Army Command and General Staff College. Archived from the original on April 30, 2008. Retrieved July 11, 2014.

- Lacey, Laura Homan (2005). Stay off the Skyline: The Sixth Marine Division on Okinawa: An Oral History. Washington, DC: Potomac Books. ISBN 9781574889529.

- Nichols Jr., Chas. S.; Shaw Jr., Henry I. "Action in the North, Chp 6 of Okinawa: Victory in the Pacific". Historical Section, Division of Public Information, U.S. Marine Corps. Archived from the original on April 13, 2010. Retrieved July 11, 2014.

- Shilin, Alan T. (January 1945). "Occupation at Tsing Tao". Marine Corps Gazette. 29 (1).