Ujamaa (lit. 'fraternity' in Swahili) was a socialist ideology that formed the basis of Julius Nyerere's social and economic development policies in Tanzania after it gained independence from Britain in 1961.[1]

More broadly, ujamaa may mean "cooperative economics", in the sense of "local people cooperating with each other to provide for the essentials of living", or "to build and maintain our own stores, shops, and other businesses and to profit from them together".[2]

Ideology and practice

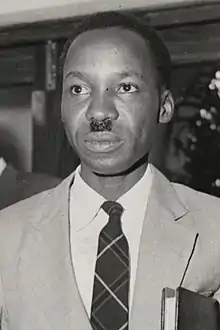

Nyerere used Ujamaa as the basis for a national development project. He translated the Ujamaa concept into the institutionalization of social, economic, and political equality through the creation of a central democracy; the abolition of discrimination based on ascribed status; and the nationalization of the economy's key sectors.[3]

Julius Nyerere's leadership of Tanzania commanded international attention and attracted worldwide respect for his consistent emphasis upon ethical principles as the basis of practical policies. Tanzania under Nyerere made great strides in vital areas of social development: infant mortality was reduced from 138 per 1000 live births in 1965 to 110 in 1985; life expectancy at birth rose from 37 in 1960 to 52 in 1984; primary school enrollment was raised from 25% of age group (only 16% of females) in 1960 to 72% (85% of females) in 1985 (despite the rapidly increasing population); the adult literacy rate rose from 17% in 1960 to 63% by 1975 (much higher than in other African countries) and continued to rise.[4] However, Ujamaa decreased production, casting doubt on the project's ability to offer economic growth.[5]

Within a year of independence, Nyerere introduced the Preventive Detention Act to crush opposition. [6]

In 1967, nationalizations transformed the government into the largest employer in the country. Purchasing power declined,[7] and, according to World Bank researchers, high taxes and bureaucracy created an environment where businessmen resorted to evasion, bribery and corruption.[7] In 1973, a policy of forced villagisation was pursued under Operation Vijiji in order to promote collective farming.[8]

The political infrastructure in independent Tanzania

The Tanzanian political infrastructure created after the 1961 independence declaration was a critical response to colonialist values. The British had held the mainland part of modern Tanzania as a mandated territory (as a former German colony) under the League of Nations after World War I. (Mandated territories could not be colonised by the responsible power, but had to be led through to self-governing independence on a reasonable timescale.) The mainland territory became known as Tanganyika Territory, and was later united with self-governing island Zanzibar (then a Protectorate of Great Britain) to form modern state of Tanzania after independence in 1964. During the colonial administration, grassroots administration was entrusted to "native courts" under the control of a local village headman or local tribal chief (the "jumbe" system). Beginning around 1960, many of the native representative leadership organizations began to become responsible for administrative obligations in the territory. These localized forms of governmental power improved the attendance of village representation. In fact, village representation and attendance at monthly meetings increased to 75% during this time.[9]

Upon the independence from British rule on December 9, 1961, the sovereign state of Tanganyika was created and was in need of a new political order (only later to be united with Zanzibar to form modern Tanzania in 1964). In the lead up to independence, the Tanganyika African National Union (TANU) was a party that was led by Julius Nyerere with a mainly rural peasant-based constituency. TANU was able to create a village-organized political structure that facilitated localization in political representation. This allowed TANU to grow in party support from 100,000 to 1,000,000 million people within only five years.[10]

TANU was able to integrate various labor and agricultural cooperatives onto their party to ensure representation of the working class population of the soon to become independent nation. The party leaders would stay in touch with local village leaders (most often the elders of the village) by taking trips known as "Safaris" and discussing issues particular to the community (a practice inherited from the colonial administration). Once borders became established, individuals were elected to represent the district. As Gerrit Huizer suggests, these elected officials were known as "Cell Boundary Commissions".[11]

Arusha Declaration

Codification and implementation of Ujamaa ideology

TANU believes that it is the responsibility of the State to intervene actively in the economic life of the Nation so as to ensure the well being of all citizens and so as to prevent the exploitation of one person by another or one group by another, and so as to prevent the accumulation of wealth to an extent inconsistent with a classless society.[12]

Ideology of self-reliance and the Five Year Plan

This expansive government spending was introduced and broken down in the Arusha Declaration two "Five Year Plans".[9] These plans promised increased agricultural and industrial production and development yields particularly in rural settings. The solution to this plan was creating "Ujamaa Villages".[9]

Even though it was necessary that Tanzania became an independent economy, the local practices of Ujamaa promoted reliance upon communities. The most important part of society according to Ujamaa ideology was the community. The individual was secondary.[13] Furthermore, Ujamaa ideology promoted the importance of communal living and a change in economic practices in regards to agricultural development that fit in line with Ujamaa ideology. Ujamaa was not only a domestic social project, but proof to the global community that African socialism could be achieved and succeed in creating a fully independent economy.

Ujamaa villages and Tanzanian villagization

Ujamaa Ideology as presented in the Arusha Declaration promoted by TANU, and promoted by President Nyerere, had significant effects on the structural development of the first Five-Year Plan. The beginning of this social and economic experiment began in Ruvuma, the southern region of Songea in Tanzania.[9]

Litowa was a success and resulted in mass movements of people in this region of Tanzania. Anthropologist John Shaw argues that, "According to President Julius Nyerere, from September 1973 to June 1975 over seven million people were moved, and from June 1975 to the end of 1976 a further four million people were moved to new settlements."[14]

Ujamaa village structure

Ujamaa villages were constructed in particular ways to emphasize community and economic self-reliance. The village was structured with homes in the center in rows with a school and a town hall as the center complex. These villages were surrounded by larger communal agricultural farms.[15] Each individual household was given about an acre or so of land to be able to harvest individual crops for their own families; however, the surrounding farm lands were created to serve as economic stimulants as structures of production.[15]

Ujamaa village structure and job description varied amongst the different settlements depending on where each village was in terms of development. Villages with less agricultural infrastructure and smaller populations would have greater divisions of labor amongst its people.[16] Many people would spend their days on the cooperatives plowing land and planting staple crops. Communities that had large populations struggled with division of labor. As larger Ujamaa villages developed, there became a problem not only with agricultural yield, but with labor practices. As Ujamaa villages became increasingly developed, people would pursue less work and would often be punished with being forced to work overtime.[17]

The TANU served a vital purpose in aiding the localized Ujamaa villages. TANU supplied larger resources such as access to clean water, construction material, and funding for supplies. Furthermore, TANU aided local communities by creating elections and forms of representation for the larger political party.[18]

Vijiji project

The Vijiji project was the Ujamaa specialized agricultural program that helped centralize agricultural production within the villagization process. Project officials ensured the population of the Ujamaa villages never fell to less than 250 households and agricultural units were divided into 10 cell units that allowed for communal living and simple representation when relaying information to TANU officials. The Vijiji project designed cities with high modernist ideology. Many academics have studied the Vijiji Project in Tanzania. Priya Lal explains that the villages were created in grid like form with houses that were bordered by a street that led to the city center.[19]

Even though this may seem as though this form of development is not unique, it was a major social transformation that rural Tanzania had not seen before. Thus, the Ujamaa program utilized the Vijiji program in the five-year plan as an example to prove that agricultural yield was possible within socialist communal living. One of the biggest failings of the Vijiji Project was the creation of misinformation. TANU officials would often record preexisting Ujamaa Villages as newly formed villages to inflate success numbers.[20]

Ujamaa and gender

The Ujamaa socialist movement not only changed many economic production practices in Tanzania but altered the ways family dynamics were pursued within Tanzania altogether—particularly, gender roles. The Ujamaa project supported of the idea of a nuclear family.[19]

The nuclear family within the later-developing villagization efforts centralized its focus on the household rather than brotherhood and communal relations, which created internal tensions between the socialist ideas of Ujamaa. In fact, it later became the cause for a struggle for power within the Ujamaa villages. However the TANU party created an entire section of government that represented women's rights and equality within society. This department was known as the Umoja wa Wanawake wa Tanganyika (UWT).[19]

The UWT, as Priya explains, was designed to address the issues concerning women's integration into a socialist society; however it became evident that the officials of the department were the wives of important TANU officials and promoted a rather patriarchal agenda.[19] There were large movements by the UWT to increase the literacy rate of women in Tanzania and institute education systems specifically for women. However, many of these academic institutions were teaching women how to become "a better wife" and further benefit the society as their role as wives.[19] For example, Lal provides the example that classes such as "Baby Care + Nutrition and Health Problems in the City"[19] were taught in these women's educational institutions. Even though the UWT later began to teach women the concepts of structural development, they were still taught it in the realm of home economics.[21]

However, men and women in rural Tanzania continued to farm their individual farms to provide subsistent yields and income for their families ("particularly their cashew plots"[22]).

Ecological effects

During the Ujamaa project there were many ecological effects that influenced both economic and political action. Academics like John Shao show the inherent contradictions that came to the forefront of Ujamaa's political and ecological undertaking.[23]

Rainfall is very important in regards to the agricultural purposes of the land. During the Ujamaa project, Shao writes "Land with only twenty inches or less... is generally not suitable for agriculture and is used mostly for grazing".[24] However, land that received thirty to forty inches of rainfall a year were used to grow staple crops as well as commercial products such as cotton.[24]

The most prominent ecological consequence during this time in Tanzania was due to the forced settlements by the TANU government and President Nyerere. During the time of forced settlement, TANU provided more artificial means of agricultural aid while cracking down on yield results and as a result, production yield began to decrease and land became underdeveloped. Land was not being utilized to its full potential and therefore, not only were crop yields subpar, but the biodiversity also became inferior.[25]

Decline and end of the Ujamaa Project

There were also internal factors that led to the implosion of the Ujamaa program. The first was resistance from the public. During the 1970s there was a resistance from the peasantry to leave their individual farms and move to communal living due to the lack of personal capital that came out of the communal farms. This led President Nyerere to order forced movement to Ujamaa villages.[26]

In popular culture

The hip-hop scene in Tanzania was greatly influenced by the key ideas and themes of Ujamaa. At the turn of the century, the principles of Ujamaa were resurrected through "an unlikely source: rappers and hip hop artists in the streets of Tanzania."[27] In response to years of corrupt government leaders and political figures after Nyerere, themes of unity and family and equality were the messages sent out in a majority of the music being produced. This was in response to the working class oppression and in some sense a form of resistance.[27] The principles of cooperative economics —"local people cooperating with each other to provide for the essentials of living"—[28] can be seen in the lyrics of many Tanzanian hip-hop artists.

Ujamaa is also the name of two African American–themed undergraduate dorms at Cornell University and Stanford University.[29]

See also

References

- ↑ Delehanty, Sean (2020). "From Modernization to Villagization: The World Bank and Ujamaa". Diplomatic History. 44 (2): 289–314. doi:10.1093/dh/dhz074.

- ↑ "Julius Nyerere, African socialist". 2005.

- ↑ Pratt, Cranford (1999). "Julius Nyerere: Reflections on the Legacy of his Socialism". Canadian Journal of African Studies. 33 (1): 137–52. doi:10.2307/486390. JSTOR 486390.

- ↑ Colin Legum, G. R. V. Mmari (1995). Mwalimu: the influence of Nyerere. Britain-Tanzania Society. ISBN 9780852553862.

- ↑ Martin Plaut, "Africa's bright future", BBC News Magazine, 2 November 2012.

- ↑ Legum, Colin; Mmari, G. R. V. (1994). Mwalimu: The Influence of Nyerere. Britain-Tanzania Society. ISBN 9780852553862.

- 1 2 Rick Stapenhurst, Sahr John Kpundeh. Curbing corruption: toward a model for building national integrity. Pp. 153-156.

- ↑ Lange, Siri. (2008) Land Tenure and Mining In Tanzania. Bergen: Chr. Michelson Institute, p. 2.

- 1 2 3 4 Huizer, Gerrit (June 1973). "Theujamaa village program in tanzania: new forms of rural development". Studies in Comparative International Development. 8 (2): 189. doi:10.1007/bf02810000. ISSN 0039-3606. S2CID 79510406.

- ↑ Huizer, Gerrit (June 1973). "Theujamaa village program in tanzania: new forms of rural development". Studies in Comparative International Development. 8 (2): 186. doi:10.1007/bf02810000. ISSN 0039-3606. S2CID 79510406.

- ↑ Huizer, Gerrit (June 1973). "Theujamaa village program in tanzania: new forms of rural development". Studies in Comparative International Development. 8 (2): 187. doi:10.1007/bf02810000. ISSN 0039-3606. S2CID 79510406.

- ↑ "Arusha Declaration" (PDF). Dar es Salaam: TANU. 1967. p. 1 – via library.fes.de.

- ↑ "Julius Nyerere | Biography, Philosophy, & Achievements | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 2022-05-24.

- ↑ Shao, John (1986). "The Villagization Program and the Disruption of the Ecological Balance in Tanzania". Canadian Journal of African Studies. 20 (2): 219–239. doi:10.2307/484871. ISSN 0008-3968. JSTOR 484871.

- 1 2 Huizer, Gerrit (June 1973). "Theujamaa village program in tanzania: new forms of rural development". Studies in Comparative International Development. 8 (2): 192. doi:10.1007/bf02810000. ISSN 0039-3606. S2CID 79510406.

- ↑ Huizer, Gerrit (June 1973). "Theujamaa village program in tanzania: new forms of rural development". Studies in Comparative International Development. 8 (2): 193. doi:10.1007/bf02810000. ISSN 0039-3606. S2CID 79510406.

- ↑ Huizer, Gerrit (June 1973). "Theujamaa village program in tanzania: new forms of rural development". Studies in Comparative International Development. 8 (2): 194. doi:10.1007/bf02810000. ISSN 0039-3606. S2CID 79510406.

- ↑ Huizer, Gerrit (June 1973). "Theujamaa village program in tanzania: new forms of rural development". Studies in Comparative International Development. 8 (2): 195. doi:10.1007/bf02810000. ISSN 0039-3606. S2CID 79510406.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 LAL, PRIYA (March 2010). "Militants, Mothers, and the National Family: Ujamaa, Gender, and Rural Development in Postcolonial Tanzania". The Journal of African History. 51 (1): 7. doi:10.1017/s0021853710000010. ISSN 0021-8537. S2CID 154960614.

- ↑ LAL, PRIYA (March 2010). "Militants, Mothers, and the National Family: Ujamaa, Gender, and Rural Development in Postcolonial Tanzania". The Journal of African History. 51 (1): 3. doi:10.1017/s0021853710000010. ISSN 0021-8537. S2CID 154960614.

- ↑ LAL, PRIYA (March 2010). "Militants, Mothers, and the National Family: Ujamaa, Gender, and Rural Development in Postcolonial Tanzania". The Journal of African History. 51 (1): 8. doi:10.1017/s0021853710000010. ISSN 0021-8537. S2CID 154960614.

- ↑ LAL, PRIYA (March 2010). "Militants, Mothers, and the National Family: Ujamaa, Gender, and Rural Development in Postcolonial Tanzania". The Journal of African History. 51 (1): 11. doi:10.1017/s0021853710000010. ISSN 0021-8537. S2CID 154960614.

- ↑ Shao, John (1986). "The Villagization Program and the Disruption of the Ecological Balance in Tanzania". Canadian Journal of African Studies. 20 (2): 222. doi:10.2307/484871. ISSN 0008-3968. JSTOR 484871.

- 1 2 Shao, John (1986). "The Villagization Program and the Disruption of the Ecological Balance in Tanzania". Canadian Journal of African Studies. 20 (2): 227. doi:10.2307/484871. ISSN 0008-3968. JSTOR 484871.

- ↑ "Tanzania - Independence | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 2022-05-15.

- ↑ Ergas, Zaki (1980). "Why Did the Ujamaa Village Policy Fail? - Towards a Global Analysis". The Journal of Modern African Studies. 18 (3): 387–410. doi:10.1017/S0022278X00011575. ISSN 0022-278X. JSTOR 160361. S2CID 154537221.

- 1 2 Lemelle, Sidney J. "‘Ni wapi Tunakwenda’: Hip Hop Culture and the Children of Arusha". In The Vinyl Ain’t Final: Hip Hop and the Globalization of Black Popular Culture, ed. Dipannita Basu and Sidney J. Lemelle, pp. 230–54. London; Ann Arbor, MI: Pluto Press.

- ↑ "Denied:1up! Software".

- ↑ "Ujamaa | Residential Education". Archived from the original on 2018-03-11. Retrieved 2018-03-28.

Further reading

- A collection of essays on Ujamaa villages, by Kayombo, E. O. [and others] University of Dar es Salaam. [Dar es Salaam] 1971.

- Paul Collier: Labour and Poverty in Rural Tanzania. Ujamaa and Rural Development in the United Republic of Tanzania. New York: Oxford University Press, 1986, ISBN 0198285310

- Nyerere, Julius K. Ujamaa. English Ujamaa--essays on socialism. Dar es Salaam, Oxford University Press, 1968.

- Building Ujamaa villages in Tanzania. Edited by J. H. Proctor. Dar es Salaam, Tanzania Pub. House, 1971.

- Huizer, Gerrit. The Ujamaa village programme in Tanzania: new forms of rural development. The Hague, Institute of Social Studies, 1971.

- Hydén, Göran (1980). Beyond ujamaa in Tanzania: underdevelopment and an uncaptured peasantry. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0520039971.

- Kijanga, Peter A. S. Ujamaa and the role of the church in Tanzania. Arusha, Tanzania : Evangelical Lutheran Church in Tanzania, c1978.

- Jennings, Michael. Surrogates of the state : NGOs, development, and Ujamaa in Tanzania Bloomfield, CT : Kumarian Press, 2008.

- McHenry, Dean E. (1979). Tanzania's ujamaa villages: the implementation of a rural development strategy. Research series - Institute of International Studies, University of California, Berkeley ; no. 39. Berkeley: Institute of International Studies, University of California. ISBN 0877251398.

- Putterman, Louis G. Peasants, collectives, and choice : economic theory and Tanzania's villages. Greenwich, Conn. : JAI Press, c1986.

- Ujamaa villages : a collection of original manuscripts, 1969-70. Dar es Salaam : [s.n.], 1970.

- Vail, David J. Technology for Ujamaa Village development in Tanzania Syracuse, N. Y. : Maxwell School of Citizenship and Public Affairs, Syracuse University, 1975.

External links

- Ibhawoh, Bonny and J.I. Dibua, "Deconstructing Ujamaa: The Legacy of Julius Nyerere in the Quest for Social and Economic Development" (PDF). (1.30 MiB) in African Journal of Political Science, Vol. 8, No. 1, 2003: pp. 59–83.

- Lawrence Cockcroft and Gerald Belkin, Ralph Ibbott: "Who conceived/led the way to Ujamaa?" in Tanzanian Affairs Issue 92, January 2009.

- Ujamaa: the hidden story of Tanzania's socialist villages Ralph Ibbott, participant, December 2014