|

|

| _Cuckoo_and_Azaleas.jpg.webp) |

- Beauty Looking Back, Moronobu, late 17th century

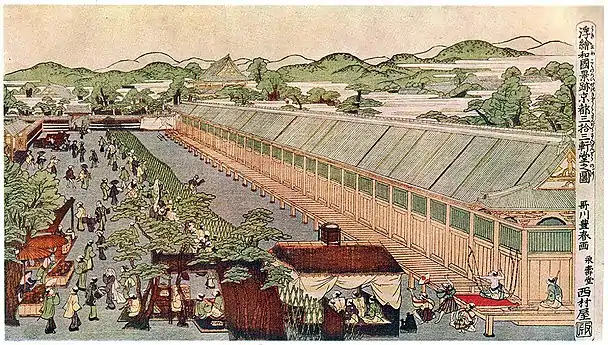

- Shibai Uki-e, Masanobu, c. 1741–1744

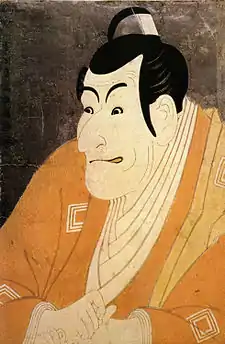

- Otani Oniji III, Sharaku, 1794

- Comb, Utamaro, 1798

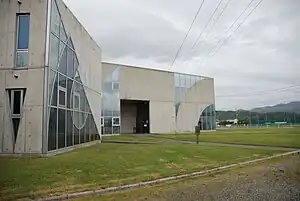

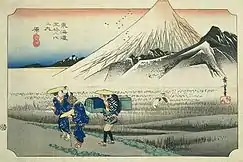

- Hara, 13th station of The Fifty-three Stations of the Tōkaidō, Hiroshige, 1833–34

- Cuckoo and Azaleas, Hokusai, 1828

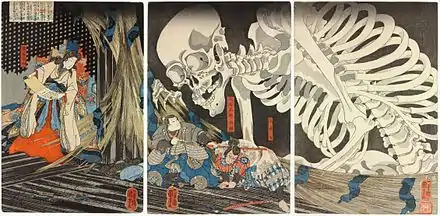

- Takiyasha the Witch and the Skeleton Spectre, Kuniyoshi, c. 1844

Ukiyo-e[lower-alpha 1] is a genre of Japanese art that flourished from the 17th through 19th centuries. Its artists produced woodblock prints and paintings of such subjects as female beauties; kabuki actors and sumo wrestlers; scenes from history and folk tales; travel scenes and landscapes; flora and fauna; and erotica. The term ukiyo-e (浮世絵) translates as 'picture[s] of the floating world'.

In 1603, the city of Edo (Tokyo) became the seat of the ruling Tokugawa shogunate. The chōnin class (merchants, craftsmen and workers), positioned at the bottom of the social order, benefited the most from the city's rapid economic growth, and began to indulge in and patronize the entertainment of kabuki theatre, geisha, and courtesans of the pleasure districts; the term ukiyo ('floating world') came to describe this hedonistic lifestyle. Printed or painted ukiyo-e works were popular with the chōnin class, who had become wealthy enough to afford to decorate their homes with them.

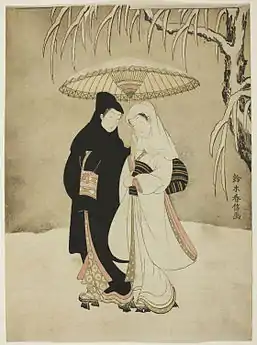

The earliest ukiyo-e works emerged in the 1670s, with Hishikawa Moronobu's paintings and monochromatic prints of beautiful women. Colour prints were introduced gradually, and at first were only used for special commissions. By the 1740s, artists such as Okumura Masanobu used multiple woodblocks to print areas of colour. In the 1760s, the success of Suzuki Harunobu's "brocade prints" led to full-colour production becoming standard, with ten or more blocks used to create each print. Some ukiyo-e artists specialized in making paintings, but most works were prints. Artists rarely carved their own woodblocks for printing; rather, production was divided between the artist, who designed the prints, the carver, who cut the woodblocks, the printer, who inked and pressed the woodblocks onto handmade paper, and the publisher, who financed, promoted, and distributed the works. As printing was done by hand, printers were able to achieve effects impractical with machines, such as the blending or gradation of colours on the printing block.

Specialists have prized the portraits of beauties and actors by masters such as Torii Kiyonaga, Utamaro, and Sharaku that came in the late 18th century. The 19th century also saw the continuation of masters of the ukiyo-e tradition, with the creation of the artist Hokusai's The Great Wave off Kanagawa, one of the most well-known works of Japanese art, and the artist Hiroshige's The Fifty-three Stations of the Tōkaidō. Following the deaths of these two masters, and against the technological and social modernization that followed the Meiji Restoration of 1868, ukiyo-e production went into steep decline. However, the 20th century saw a revival in Japanese printmaking: the shin-hanga ('new prints') genre capitalized on Western interest in prints of traditional Japanese scenes, and the sōsaku-hanga ('creative prints') movement promoted individualist works designed, carved, and printed by a single artist. Prints since the late 20th century have continued in an individualist vein, often made with techniques imported from the West.

Ukiyo-e was central to forming the West's perception of Japanese art in the late 19th century, particularly the landscapes of Hokusai and Hiroshige. From the 1870s onwards, Japonisme became a prominent trend and had a strong influence on the early Impressionists such as Edgar Degas, Édouard Manet and Claude Monet, as well as influencing Post-Impressionists such as Vincent van Gogh, and Art Nouveau artists such as Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec.

History

Pre-history

Japanese art since the Heian period (794–1185) had followed two principal paths: the nativist Yamato-e tradition, focusing on Japanese themes, best known by the works of the Tosa school; and Chinese-inspired kara-e in a variety of styles, such as the monochromatic ink wash paintings of Sesshū Tōyō and his disciples. The Kanō school of painting incorporated features of both.[1]

Since antiquity, Japanese art had found patrons in the aristocracy, military governments, and religious authorities.[2] Until the 16th century, the lives of the common people had not been a main subject of painting, and even when they were included, the works were luxury items made for the ruling samurai and rich merchant classes.[3] Later works appeared by and for townspeople, including inexpensive monochromatic paintings of female beauties and scenes of the theatre and pleasure districts. The hand-produced nature of these shikomi-e (仕込絵) limited the scale of their production, a limit that was soon overcome by genres that turned to mass-produced woodblock printing.[4]

During a prolonged period of civil war in the 16th century, a class of politically powerful merchants developed. These machishū, the predecessors of the Edo period's chōnin, allied themselves with the court and had power over local communities; their patronage of the arts encouraged a revival in the classical arts in the late 16th and early 17th centuries.[5] In the early 17th century, Tokugawa Ieyasu (1543–1616) unified the country and was appointed shōgun with supreme power over Japan. He consolidated his government in the village of Edo (modern Tokyo),[6] and required the territorial lords to assemble there in alternate years with their entourages. The demands of the growing capital drew many male labourers from the country, so that males came to make up nearly seventy percent of the population.[7] The village grew during the Edo period (1603–1867) from a population of 1800 to over a million in the 19th century.[6]

The centralized shogunate put an end to the power of the machishū and divided the population into four social classes, with the ruling samurai class at the top and the merchant class at the bottom. While deprived of their political influence,[5] those of the merchant class most benefited from the rapidly expanding economy of the Edo period,[8] and their improved lot allowed for leisure that many sought in the pleasure districts—in particular Yoshiwara in Edo[6]—and collecting artworks to decorate their homes, which in earlier times had been well beyond their financial means.[9] The experience of the pleasure quarters was open to those of sufficient wealth, manners, and education.[10]

Woodblock printing in Japan traces back to the Hyakumantō Darani in 770 CE. Until the 17th century, such printing was reserved for Buddhist seals and images.[11] Movable type appeared around 1600, but as the Japanese writing system required about 100,000 type pieces,[lower-alpha 2] hand-carving text onto woodblocks was more efficient. In Saga, Kyoto, calligrapher Hon'ami Kōetsu and publisher Suminokura Soan combined printed text and images in an adaptation of The Tales of Ise (1608) and other works of literature.[12] During the Kan'ei era (1624–1643) illustrated books of folk tales called tanrokubon ('orange-green books') were the first books mass-produced using woodblock printing.[11] Woodblock imagery continued to evolve as illustrations to the kanazōshi genre of tales of hedonistic urban life in the new capital.[13] The rebuilding of Edo following the Great Fire of Meireki in 1657 occasioned a modernization of the city, and the publication of illustrated printed books flourished in the rapidly urbanizing environment.[14]

The term ukiyo (浮世), which can be translated as 'floating world', was homophonous with the ancient Buddhist term ukiyo (憂き世), meaning 'this world of sorrow and grief'. The newer term at times was used to mean 'erotic' or 'stylish', among other meanings, and came to describe the hedonistic spirit of the time for the lower classes. Asai Ryōi celebrated this spirit in the novel Ukiyo Monogatari (Tales of the Floating World, c. 1661):[15]

[L]iving only for the moment, savouring the moon, the snow, the cherry blossoms, and the maple leaves, singing songs, drinking sake, and diverting oneself just in floating, unconcerned by the prospect of imminent poverty, buoyant and carefree, like a gourd carried along with the river current: this is what we call ukiyo.

Emergence of ukiyo-e (late 17th – early 18th centuries)

The earliest ukiyo-e artists came from the world of Japanese painting.[16] Yamato-e painting of the 17th century had developed a style of outlined forms which allowed inks to be dripped on a wet surface and spread out towards the outlines—this outlining of forms was to become the dominant style of ukiyo-e.[17]

Around 1661, painted hanging scrolls known as Portraits of Kanbun Beauties gained popularity. The paintings of the Kanbun era (1661–1673), most of which are anonymous, marked the beginnings of ukiyo-e as an independent school.[16] The paintings of Iwasa Matabei (1578–1650) have a great affinity with ukiyo-e paintings. Scholars disagree whether Matabei's work itself is ukiyo-e;[18] assertions that he was the genre's founder are especially common amongst Japanese researchers.[19] At times Matabei has been credited as the artist of the unsigned Hikone screen,[20] a byōbu folding screen that may be one of the earliest surviving ukiyo-e works. The screen is in a refined Kanō style and depicts contemporary life, rather than the prescribed subjects of the painterly schools.[21]

In response to the increasing demand for ukiyo-e works, Hishikawa Moronobu (1618–1694) produced the first ukiyo-e woodblock prints.[16] By 1672, Moronobu's success was such that he began to sign his work—the first of the book illustrators to do so. He was a prolific illustrator who worked in a wide variety of genres, and developed an influential style of portraying female beauties. Most significantly, he began to produce illustrations, not just for books, but as single-sheet images, which could stand alone or be used as part of a series. The Hishikawa school attracted a large number of followers,[22] as well as imitators such as Sugimura Jihei,[23] and signalled the beginning of the popularization of a new artform.[24]

Torii Kiyonobu I and Kaigetsudō Ando became prominent emulators of Moronobu's style following the master's death, though neither was a member of the Hishikawa school. Both discarded background detail in favour of focus on the human figure—kabuki actors in the yakusha-e of Kiyonobu and the Torii school that followed him,[25] and courtesans in the bijin-ga of Ando and his Kaigetsudō school. Ando and his followers produced a stereotyped female image whose design and pose lent itself to effective mass production,[26] and its popularity created a demand for paintings that other artists and schools took advantage of.[27] The Kaigetsudō school and its popular "Kaigetsudō beauty" ended after Ando's exile over his role in the Ejima-Ikushima scandal of 1714.[28]

Kyoto native Nishikawa Sukenobu (1671–1750) painted technically refined pictures of courtesans.[29] Considered a master of erotic portraits, he was the subject of a government ban in 1722, though it is believed he continued to create works that circulated under different names.[30] Sukenobu spent most of his career in Edo, and his influence was considerable in both the Kantō and Kansai regions.[29] The paintings of Miyagawa Chōshun (1683–1752) portrayed early 18th-century life in delicate colours. Chōshun made no prints.[31] The Miyagawa school he founded in the early-18th century specialized in romantic paintings in a style more refined in line and colour than the Kaigetsudō school. Chōshun allowed greater expressive freedom in his adherents, a group that later included Hokusai.[27]

- Early ukiyo-e masters

Standing portrait of a courtesanInk and colour painting on silk, Kaigetsudō Ando, c. 1705–10

Standing portrait of a courtesanInk and colour painting on silk, Kaigetsudō Ando, c. 1705–10 Portrait of actorsHand-coloured printKiyonobu, 1714

Portrait of actorsHand-coloured printKiyonobu, 1714 Printed page from Asakayama E-honSukenobu, 1739

Printed page from Asakayama E-honSukenobu, 1739 Ryukyuan Dancer and MusiciansInk and color painting on silk, Chōshun, c. 1718

Ryukyuan Dancer and MusiciansInk and color painting on silk, Chōshun, c. 1718

Colour prints (mid-18th century)

Even in the earliest monochromatic prints and books, colour was added by hand for special commissions. Demand for colour in the early-18th century was met with tan-e[lower-alpha 3] prints hand-tinted with orange and sometimes green or yellow.[33] These were followed in the 1720s with a vogue for pink-tinted beni-e[lower-alpha 4] and later the lacquer-like ink of the urushi-e. In 1744, the benizuri-e were the first successes in colour printing, using multiple woodblocks—one for each colour, the earliest beni pink and vegetable green.[34]

A great self-promoter, Okumura Masanobu (1686–1764) played a major role during the period of rapid technical development in printing from the late 17th to mid-18th centuries.[34] He established a shop in 1707[35] and combined elements of the leading contemporary schools in a wide array of genres, though Masanobu himself belonged to no school. Amongst the innovations in his romantic, lyrical images were the introduction of geometrical perspective in the uki-e genre[lower-alpha 5] in the 1740s;[39] the long, narrow hashira-e prints; and the combination of graphics and literature in prints that included self-penned haiku poetry.[40]

Ukiyo-e reached a peak in the late 18th century with the advent of full-colour prints, developed after Edo returned to prosperity under Tanuma Okitsugu following a long depression.[41] These popular colour prints came to be called nishiki-e, or 'brocade pictures', as their brilliant colours seemed to bear resemblance to imported Chinese Shuchiang brocades, known in Japanese as Shokkō nishiki.[42] The first to emerge were expensive calendar prints, printed with multiple blocks on very fine (or finer than standard) paper with heavy, opaque inks. These prints had the number of days for each month hidden in the design, and were sent at the New Year[lower-alpha 6] as personalized greetings, bearing the name of the patron rather than the artist. The blocks for these prints were later re-used for commercial production, obliterating the patron's name and replacing it with that of the artist.[43]

The delicate, romantic prints of Suzuki Harunobu (1725–1770) were amongst the first to realize expressive and complex colour designs,[44] printed with up to a dozen separate blocks to handle the different colours[45] and half-tones.[46] His restrained, graceful prints invoked the classicism of waka poetry and Yamato-e painting. The prolific Harunobu was the dominant ukiyo-e artist of his time.[47] The success of Harunobu's colourful nishiki-e from 1765 on led to a steep decline in demand for the limited palettes of benizuri-e and urushi-e, as well as hand-coloured prints.[45]

A trend against the idealism of the prints of Harunobu and the Torii school grew following Harunobu's death in 1770. Katsukawa Shunshō (1726–1793) and his school produced portraits of kabuki actors with greater fidelity to the actors' actual features than had been the trend.[48] Sometime-collaborators Koryūsai (1735 – c. 1790) and Kitao Shigemasa (1739–1820) were prominent depicters of women who also moved ukiyo-e away from the dominance of Harunobu's idealism by focusing on contemporary urban fashions and celebrated real-world courtesans and geisha.[49] Koryūsai was perhaps the most prolific ukiyo-e artist of the 18th century, and produced a larger number of paintings and print series than any predecessor.[50] The Kitao school that Shigemasa founded was one of the dominant schools of the closing decades of the 18th century.[51]

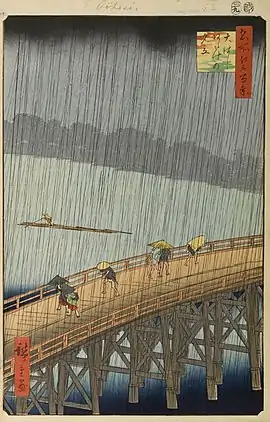

In the 1770s, Utagawa Toyoharu produced a number of uki-e perspective prints[52] that demonstrated a mastery of Western perspective techniques that had eluded his predecessors in the genre.[36] Toyoharu's works helped pioneer the landscape as an ukiyo-e subject, rather than merely a background for human figures.[53] In the 19th century, Western-style perspective techniques were absorbed into Japanese artistic culture, and deployed in the refined landscapes of such artists as Hokusai and Hiroshige,[54] the latter a member of the Utagawa school that Toyoharu founded. This school was to become one of the most influential,[55] and produced works in a far greater variety of genres than any other school.[56]

Peak period (late 18th century)

While the late 18th century saw hard economic times,[57] ukiyo-e saw a peak in quantity and quality of works, particularly during the Kansei era (1789–1791).[58] The ukiyo-e of the period of the Kansei Reforms brought about a focus on beauty and harmony[51] that collapsed into decadence and disharmony in the next century as the reforms broke down and tensions rose, culminating in the Meiji Restoration of 1868.[58]

Especially in the 1780s, Torii Kiyonaga (1752–1815)[51] of the Torii school[58] depicted traditional ukiyo-e subjects like beauties and urban scenes, which he printed on large sheets of paper, often as multiprint horizontal diptychs or triptychs. His works dispensed with the poetic dreamscapes made by Harunobu, opting instead for realistic depictions of idealized female forms dressed in the latest fashions and posed in scenic locations.[59] He also produced portraits of kabuki actors in a realistic style that included accompanying musicians and chorus.[60]

A law went into effect in 1790 requiring prints to bear a censor's seal of approval to be sold. Censorship increased in strictness over the following decades, and violators could receive harsh punishments. From 1799 even preliminary drafts required approval.[61] A group of Utagawa-school offenders including Toyokuni had their works repressed in 1801, and Utamaro was imprisoned in 1804 for making prints of 16th-century political and military leader Toyotomi Hideyoshi.[62]

Utamaro (c. 1753–1806) made his name in the 1790s with his bijin ōkubi-e ('large-headed pictures of beautiful women') portraits, focusing on the head and upper torso, a style others had previously employed in portraits of kabuki actors.[63] Utamaro experimented with line, colour, and printing techniques to bring out subtle differences in the features, expressions, and backdrops of subjects from a wide variety of class and background. Utamaro's individuated beauties were in sharp contrast to the stereotyped, idealized images that had been the norm.[64] By the end of the decade, especially following the death of his patron Tsutaya Jūzaburō in 1797, Utamaro's prodigious output declined in quality,[65] and he died in 1806.[66]

Appearing suddenly in 1794 and disappearing just as suddenly ten months later, the prints of the enigmatic Sharaku are amongst ukiyo-e's best known. Sharaku produced striking portraits of kabuki actors, introducing a greater level of realism into his prints that emphasized the differences between the actor and the portrayed character.[67] The expressive, contorted faces he depicted contrasted sharply with the serene, mask-like faces more common to artists such as Harunobu or Utamaro.[46] Published by Tsutaya,[66] Sharaku's work found resistance, and in 1795 his output ceased as mysteriously as it had appeared; his real identity is still unknown.[68] Utagawa Toyokuni (1769–1825) produced kabuki portraits in a style Edo townsfolk found more accessible, emphasizing dramatic postures and avoiding Sharaku's realism.[67]

A consistent high level of quality marks ukiyo-e of the late 18th-century, but the works of Utamaro and Sharaku often overshadow those other masters of the era.[66] One of Kiyonaga's followers,[58] Eishi (1756–1829), abandoned his position as painter for shōgun Tokugawa Ieharu to take up ukiyo-e design. He brought a refined sense to his portraits of graceful, slender courtesans, and left behind a number of noted students.[66] With a fine line, Eishōsai Chōki (fl. 1786–1808) designed portraits of delicate courtesans. The Utagawa school came to dominate ukiyo-e output in the late Edo period.[69]

Edo was the primary centre of ukiyo-e production throughout the Edo period. Another major centre developed in the Kamigata region of areas in and around Kyoto and Osaka. In contrast to the range of subjects in the Edo prints, those of Kamigata tended to be portraits of kabuki actors. The style of the Kamigata prints was little distinguished from those of Edo until the late 18th century, partly because artists often moved back and forth between the two areas.[70] Colours tend to be softer and pigments thicker in Kamigata prints than in those of Edo.[71] In the 19th century many of the prints were designed by kabuki fans and other amateurs.[72]

Late flowering: flora, fauna, and landscapes (19th century)

The Tenpō Reforms of 1841–1843 sought to suppress outward displays of luxury, including the depiction of courtesans and actors. As a result, many ukiyo-e artists designed travel scenes and pictures of nature, especially birds and flowers.[73] Landscapes had been given limited attention since Moronobu, and they formed an important element in the works of Kiyonaga and Shunchō. It was not until late in the Edo period that landscape came into its own as a genre, especially via the works of Hokusai and Hiroshige The landscape genre has come to dominate Western perceptions of ukiyo-e, though ukiyo-e had a long history preceding these late-era masters.[74] The Japanese landscape differed from the Western tradition in that it relied more heavily on imagination, composition, and atmosphere than on strict observance of nature.[75]

The self-proclaimed "mad painter" Hokusai (1760–1849) enjoyed a long, varied career. His work is marked by a lack of the sentimentality common to ukiyo-e, and a focus on formalism influenced by Western art. Among his accomplishments are his illustrations of Takizawa Bakin's novel Crescent Moon, his series of sketchbooks, the Hokusai Manga, and his popularization of the landscape genre with Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji,[76] which includes his best-known print, The Great Wave off Kanagawa,[77] one of the most famous works of Japanese art.[78] In contrast to the work of the older masters, Hokusai's colours were bold, flat, and abstract, and his subject was not the pleasure districts but the lives and environment of the common people at work.[79] Established masters Eisen, Kuniyoshi, and Kunisada also followed Hokusai's steps into landscape prints in the 1830s, producing prints with bold compositions and striking effects.[80]

Though not often given the attention of their better-known forebears, the Utagawa school produced a few masters in this declining period. The prolific Kunisada (1786–1865) had few rivals in the tradition of making portrait prints of courtesans and actors.[81] One of those rivals was Eisen (1790–1848), who was also adept at landscapes.[82] Perhaps the last significant member of this late period, Kuniyoshi (1797–1861) tried his hand at a variety of themes and styles, much as Hokusai had. His historical scenes of warriors in violent combat were popular,[83] especially his series of heroes from the Suikoden (1827–1830) and Chūshingura (1847).[84] He was adept at landscapes and satirical scenes—the latter an area rarely explored in the dictatorial atmosphere of the Edo period; that Kuniyoshia could dare tackle such subjects was a sign of the weakening of the shogunate at the time.[83]

Hiroshige (1797–1858) is considered Hokusai's greatest rival in stature. He specialized in pictures of birds and flowers, and serene landscapes, and is best known for his travel series, such as The Fifty-three Stations of the Tōkaidō and The Sixty-nine Stations of the Kisokaidō,[85] the latter a cooperative effort with Eisen.[82] His work was more realistic, subtly coloured, and atmospheric than Hokusai's; nature and the seasons were key elements: mist, rain, snow, and moonlight were prominent parts of his compositions.[86] Hiroshige's followers, including adopted son Hiroshige II and son-in-law Hiroshige III, carried on their master's style of landscapes into the Meiji era.[87]

- Masters of the late period

_Dawn_at_Futami-ga-ura.jpg.webp) Dawn at Futami-ga-uraKunisada, c. 1832

Dawn at Futami-ga-uraKunisada, c. 1832

_Two_mandarin_ducks.jpg.webp) Two mandarin ducksHiroshige, 1838

Two mandarin ducksHiroshige, 1838

Decline (late 19th century)

Following the deaths of Hokusai and Hiroshige[88] and the Meiji Restoration of 1868, ukiyo-e suffered a sharp decline in quantity and quality.[89] The rapid Westernization of the Meiji period that followed saw woodblock printing turn its services to journalism, and face competition from photography. Practitioners of pure ukiyo-e became more rare, and tastes turned away from a genre seen as a remnant of an obsolescent era.[88] Artists continued to produce occasional notable works, but by the 1890s the tradition was moribund.[90]

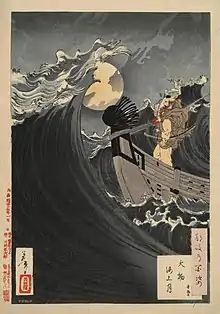

Synthetic pigments imported from Germany began to replace traditional organic ones in the mid-19th century. Many prints from this era made extensive use of a bright red, and were called aka-e ('red pictures').[91] Artists such as Yoshitoshi (1839–1892) led a trend in the 1860s of gruesome scenes of murders and ghosts,[92] monsters and supernatural beings, and legendary Japanese and Chinese heroes. His One Hundred Aspects of the Moon (1885–1892) depicts a variety of fantastic and mundane themes with a moon motif.[93] Kiyochika (1847–1915) is known for his prints documenting the rapid modernization of Tokyo, such as the introduction of railways, and his depictions of Japan's wars with China and with Russia.[92] Earlier a painter of the Kanō school, in the 1870s Chikanobu (1838–1912) turned to prints, particularly of the imperial family and scenes of Western influence on Japanese life in the Meiji period.[94]

- Meiji-era ukiyo-e

_Mirror_of_Japanese_Nobility_(cropped_and_rotated).jpg.webp) Mirror of the Japanese NobilityChikanobu, 1887

Mirror of the Japanese NobilityChikanobu, 1887 From One Hundred Aspects of the MoonYoshitoshi, 1891

From One Hundred Aspects of the MoonYoshitoshi, 1891_Nichiro_Jinsenk-o_kaisen_dai_Nihon_kaigundaish%C5%8Dri_Banzai.jpg.webp) Russo-Japanese Naval Battle at the Entrance of Incheon: The Great Victory of the Japanese Navy—Banzai!Kiyochika, 1904

Russo-Japanese Naval Battle at the Entrance of Incheon: The Great Victory of the Japanese Navy—Banzai!Kiyochika, 1904

Introduction to the West

Aside from Dutch traders, who had had trading relations dating to the beginning of the Edo period,[95] Westerners paid little notice to Japanese art before the mid-19th century, and when they did they rarely distinguished it from other art from the East.[95] Swedish naturalist Carl Peter Thunberg spent a year in the Dutch trading settlement Dejima, near Nagasaki, and was one of the earliest Westerners to collect Japanese prints. The export of ukiyo-e thereafter slowly grew, and at the beginning of the 19th century Dutch merchant-trader Isaac Titsingh's collection drew the attention of connoisseurs of art in Paris.[96]

The arrival in Edo of American Commodore Matthew Perry in 1853 led to the Convention of Kanagawa in 1854, which opened Japan to the outside world after over two centuries of seclusion. Ukiyo-e prints were amongst the items he brought back to the United States.[97] Such prints had appeared in Paris from at least the 1830s, and by the 1850s were numerous;[98] reception was mixed, and even when praised ukiyo-e was generally thought inferior to Western works which emphasized mastery of naturalistic perspective and anatomy.[99] Japanese art drew notice at the International Exhibition of 1867 in Paris,[95] and became fashionable in France and England in the 1870s and 1880s.[95] The prints of Hokusai and Hiroshige played a prominent role in shaping Western perceptions of Japanese art.[100] At the time of their introduction to the West, woodblock printing was the most common mass medium in Japan, and the Japanese considered it of little lasting value.[101]

Early Europeans promoters and scholars of ukiyo-e and Japanese art included writer Edmond de Goncourt and art critic Philippe Burty,[102] who coined the term Japonism.[103][lower-alpha 7] Stores selling Japanese goods opened, including those of Édouard Desoye in 1862 and art dealer Siegfried Bing in 1875.[104] From 1888 to 1891 Bing published the magazine Artistic Japan[105] in English, French, and German editions,[106] and curated an ukiyo-e exhibition at the École des Beaux-Arts in 1890 attended by artists such as Mary Cassatt.[107]

American Ernest Fenollosa was the earliest Western devotee of Japanese culture, and did much to promote Japanese art—Hokusai's works featured prominently at his inaugural exhibition as first curator of Japanese art Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, and in Tokyo in 1898 he curated the first ukiyo-e exhibition in Japan.[108] By the end of the 19th century, the popularity of ukiyo-e in the West drove prices beyond the means of most collectors—some, such as Degas, traded their own paintings for such prints. Tadamasa Hayashi was a prominent Paris-based dealer of respected tastes whose Tokyo office was responsible for evaluating and exporting large quantities of ukiyo-e prints to the West in such quantities that Japanese critics later accused him of siphoning Japan of its national treasure.[109] The drain first went unnoticed in Japan, as Japanese artists were immersing themselves in the classical painting techniques of the West.[110]

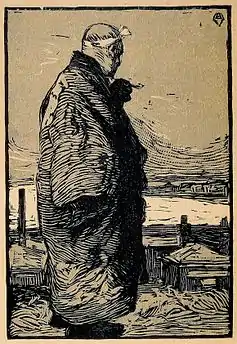

Japanese art, and particularly ukiyo-e prints, came to influence Western art from the time of the early Impressionists.[111] Early painter-collectors incorporated Japanese themes and compositional techniques into their works as early as the 1860s:[98] the patterned wallpapers and rugs in Manet's paintings were inspired by the patterned kimono found in ukiyo-e pictures, and Whistler focused his attention on ephemeral elements of nature as in ukiyo-e landscapes.[112] Van Gogh was an avid collector, and painted copies in oil of prints by Hiroshige and Eisen.[113] Degas and Cassatt depicted fleeting, everyday moments in Japanese-influenced compositions and perspectives.[114] ukiyo-e's flat perspective and unmodulated colours were a particular influence on graphic designers and poster makers.[115] Toulouse-Lautrec's lithographs displayed his interest not only in ukiyo-e's flat colours and outlined forms, but also in their subject matter: performers and prostitutes.[116] He signed much of this work with his initials in a circle, imitating the seals on Japanese prints.[116] Other artists of the time who drew influence from ukiyo-e include Monet,[111] La Farge,[117] Gauguin,[118] and Les Nabis members such as Bonnard[119] and Vuillard.[120] French composer Claude Debussy drew inspiration for his music from the prints of Hokusai and Hiroshige, most prominently in La mer (1905).[121] Imagist poets such as Amy Lowell and Ezra Pound found inspiration in ukiyo-e prints; Lowell published a book of poetry called Pictures of the Floating World (1919) on oriental themes or in an oriental style.[122]

- Ukiyo-e influence on Western art

Bamboo Yards, Kyōbashi BridgeHiroshige, c. 1857–58

Bamboo Yards, Kyōbashi BridgeHiroshige, c. 1857–58

Sudden Shower over Shin-Ōhashi bridge and AtakeHiroshige, 1857

Sudden Shower over Shin-Ōhashi bridge and AtakeHiroshige, 1857

_c1879-1880.jpg.webp) Mary Cassatt at the Louvre: The Paintings GalleryDegas, c. 1879–80

Mary Cassatt at the Louvre: The Paintings GalleryDegas, c. 1879–80 Woman BathingCassatt, c. 1890–91

Woman BathingCassatt, c. 1890–91

Descendant traditions (20th century)

The travel sketchbook became a popular genre beginning about 1905, as the Meiji government promoted travel within Japan to have citizens better know their country.[123] In 1915, publisher Shōzaburō Watanabe introduced the term shin-hanga ("new prints") to describe a style of prints he published that featured traditional Japanese subject matter and were aimed at foreign and upscale Japanese audiences.[124] Prominent artists included Goyō Hashiguchi, called the "Utamaro of the Taishō period" for his manner of depicting women; Shinsui Itō, who brought more modern sensibilities to images of women;[125] and Hasui Kawase, who made modern landscapes.[126] Watanabe also published works by non-Japanese artists, an early success of which was a set of Indian- and Japanese-themed prints in 1916 by the English Charles W. Bartlett (1860–1940). Other publishers followed Watanabe's success, and some shin-hanga artists such as Goyō and Hiroshi Yoshida set up studios to publish their own work.[127]

Artists of the sōsaku-hanga ('creative prints') movement took control of every aspect of the printmaking process—design, carving, and printing were by the same pair of hands.[124] Kanae Yamamoto (1882–1946), then a student at the Tokyo School of Fine Arts, is credited with the birth of this approach. In 1904, he produced Fisherman using woodblock printing, a technique until then frowned upon by the Japanese art establishment as old-fashioned and for its association with commercial mass production.[128] The foundation of the Japanese Woodcut Artists' Association in 1918 marks the beginning of this approach as a movement.[129] The movement favoured individuality in its artists, and as such has no dominant themes or styles.[130] Works ranged from the entirely abstract ones of Kōshirō Onchi (1891–1955) to the traditional figurative depictions of Japanese scenes of Un'ichi Hiratsuka (1895–1997).[129] These artists produced prints not because they hoped to reach a mass audience, but as a creative end in itself, and did not restrict their print media to the woodblock of traditional ukiyo-e.[131]

Prints from the late-20th and 21st centuries have evolved from the concerns of earlier movements, especially the sōsaku-hanga movement's emphasis on individual expression. Screen printing, etching, mezzotint, mixed media, and other Western methods have joined traditional woodcutting amongst printmakers' techniques.[132]

- Descendants of ukiyo-e

Taj Mahal, Charles W. Bartlett, 1916

Taj Mahal, Charles W. Bartlett, 1916 Combing the HairGoyō Hashiguchi, 1920

Combing the HairGoyō Hashiguchi, 1920 Shiba Zōjōji, Hasui Kawase, 1925

Shiba Zōjōji, Hasui Kawase, 1925 Lyric No. 23Kōshirō Onchi, 1952

Lyric No. 23Kōshirō Onchi, 1952

Style

Early ukiyo-e artists brought with them a sophisticated knowledge of and training in the composition principles of classical Chinese painting; gradually these artists shed the overt Chinese influence to develop a native Japanese idiom. The early ukiyo-e artists have been called "Primitives" in the sense that the print medium was a new challenge to which they adapted these centuries-old techniques—their image designs are not considered "primitive".[133] Many ukiyo-e artists received training from teachers of the Kanō and other painterly schools.[134]

A defining feature of most ukiyo-e prints is a well-defined, bold, flat line.[135] The earliest prints were monochromatic, and these lines were the only printed element; even with the advent of colour this characteristic line continued to dominate.[136] In ukiyo-e composition forms are arranged in flat spaces[137] with figures typically in a single plane of depth. Attention was drawn to vertical and horizontal relationships, as well as details such as lines, shapes, and patterns such as those on clothing.[138] Compositions were often asymmetrical, and the viewpoint was often from unusual angles, such as from above. Elements of images were often cropped, giving the composition a spontaneous feel.[139] In colour prints, contours of most colour areas are sharply defined, usually by the linework.[140] The aesthetic of flat areas of colour contrasts with the modulated colours expected in Western traditions[137] and with other prominent contemporary traditions in Japanese art patronized by the upper class, such as in the subtle monochrome ink brushstrokes of zenga brush painting or tonal colours of the Kanō school of painting.[140]

The colourful, ostentatious, and complex patterns, concern with changing fashions, and tense, dynamic poses and compositions in ukiyo-e are in striking contrast with many concepts in traditional Japanese aesthetics. Prominent amongst these, wabi-sabi favours simplicity, asymmetry, and imperfection, with evidence of the passage of time;[141] and shibui values subtlety, humility, and restraint.[142] Ukiyo-e can be less at odds with aesthetic concepts such as the racy, urbane stylishness of iki.[143]

ukiyo-e displays an unusual approach to graphical perspective, one that can appear underdeveloped when compared to European paintings of the same period. Western-style geometrical perspective was known in Japan—practised most prominently by the Akita ranga painters of the 1770s—as were Chinese methods to create a sense of depth using a homogeny of parallel lines. The techniques sometimes appeared together in ukiyo-e works, geometrical perspective providing an illusion of depth in the background and the more expressive Chinese perspective in the fore.[144] The techniques were most likely learned at first through Chinese Western-style paintings rather than directly from Western works.[145] Long after becoming familiar with these techniques, artists continued to harmonize them with traditional methods according to their compositional and expressive needs.[146] Other ways of indicating depth included the Chinese tripartite composition method used in Buddhist pictures, where a large form is placed in the foreground, a smaller in the midground, and yet a smaller in the background; this can be seen in Hokusai's Great Wave, with a large boat in the foreground, a smaller behind it, and a small Mt Fuji behind them.[147]

There was a tendency since early ukiyo-e to pose beauties in what art historian Midori Wakakura called a "serpentine posture",[lower-alpha 8] which involves the subjects' bodies twisting unnaturally while facing behind themselves. Art historian Motoaki Kōno posited that this had its roots in traditional buyō dance; Haruo Suwa countered that the poses were artistic licence taken by ukiyo-e artists, causing a seemingly relaxed pose to reach unnatural or impossible physical extremes. This remained the case even when realistic perspective techniques were applied to other sections of the composition.[148]

Themes and genres

Typical subjects were female beauties ("bijin-ga"), kabuki actors ("yakusha-e"), and landscapes. The women depicted were most often courtesans and geisha at leisure, and promoted the entertainments to be found in the pleasure districts.[149] The detail with which artists depicted courtesans' fashions and hairstyles allows the prints to be dated with some reliability. Less attention was given to accuracy of the women's physical features, which followed the day's pictorial fashions—the faces stereotyped, the bodies tall and lanky in one generation and petite in another.[150] Portraits of celebrities were much in demand, in particular those from the kabuki and sumo worlds, two of the most popular entertainments of the era.[151] While the landscape has come to define ukiyo-e for many Westerners, landscapes flourished relatively late in the ukiyo-e's history.[74]

Ukiyo-e prints grew out of book illustration—many of Moronobu's earliest single-page prints were originally pages from books he had illustrated.[12] E-hon books of illustrations were popular[152] and continued be an important outlet for ukiyo-e artists. In the late period, Hokusai produced the three-volume One Hundred Views of Mount Fuji and the 15-volume Hokusai Manga, the latter a compendium of over 4000 sketches of a wide variety of realistic and fantastic subjects.[153]

Traditional Japanese religions do not consider sex or pornography a moral corruption in the sense of most Abrahamic faiths,[154] and until the changing morals of the Meiji era led to its suppression, shunga erotic prints were a major genre.[155] While the Tokugawa regime subjected Japan to strict censorship laws, pornography was not considered an important offence and generally met with the censors' approval.[62] Many of these prints displayed a high level a draughtsmanship, and often humour, in their explicit depictions of bedroom scenes, voyeurs, and oversized anatomy.[156] As with depictions of courtesans, these images were closely tied to entertainments of the pleasure quarters.[157] Nearly every ukiyo-e master produced shunga at some point.[158] Records of societal acceptance of shunga are absent, though Timon Screech posits that there were almost certainly some concerns over the matter, and that its level of acceptability has been exaggerated by later collectors, especially in the West.[157]

Scenes from nature have been an important part of Asian art throughout history. Artists have closely studied the correct forms and anatomy of plants and animals, even though depictions of human anatomy remained more fanciful until modern times. Ukiyo-e nature prints are called kachō-e, which translates as "flower-and-bird pictures", though the genre was open to more than just flowers or birds, and the flowers and birds did not necessarily appear together.[73] Hokusai's detailed, precise nature prints are credited with establishing kachō-e as a genre.[159]

The Tenpō Reforms of the 1840s suppressed the depiction of actors and courtesans. Aside from landscapes and kachō-e, artists turned to depictions of historical scenes, such as of ancient warriors or of scenes from legend, literature, and religion. The 11th century Tale of Genji[160] and the 13th-century Tale of the Heike[161] have been sources of artistic inspiration throughout Japanese history,[160] including in ukiyo-e.[160] Well-known warriors and swordsmen such as Miyamoto Musashi (1584–1645) were frequent subjects, as were depictions of monsters, the supernatural, and heroes of Japanese and Chinese mythology.[162]

From the 17th to 19th centuries Japan isolated itself from the rest of the world. Trade, primarily with the Dutch and Chinese, was restricted to the island of Dejima near Nagasaki. Outlandish pictures called Nagasaki-e were sold to tourists of the foreigners and their wares.[97] In the mid-19th century, Yokohama became the primary foreign settlement after 1859, from which Western knowledge proliferated in Japan.[163] Especially from 1858 to 1862, Yokohama-e prints documented, with various levels of fact and fancy, the growing community of world denizens with whom the Japanese were now coming in contact;[164] triptychs of scenes of Westerners and their technology were particularly popular.[165]

Specialized prints included surimono, deluxe, limited-edition prints aimed at connoisseurs, of which a five-line kyōka poem was usually part of the design;[166] and uchiwa-e printed hand fans, which often suffer from having been handled.[12]

- Ukiyo-e genres

_-_Peonies_and_Canary_(Shakuyaku%252C_kanaari)%252C_from_an_untitled_series_known_as_Small_Flowers_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg.webp)

_English_Couple_(crop).jpg.webp) English CoupleYokohama-e by Utagawa Yoshitora, 1860

English CoupleYokohama-e by Utagawa Yoshitora, 1860

Production

Paintings

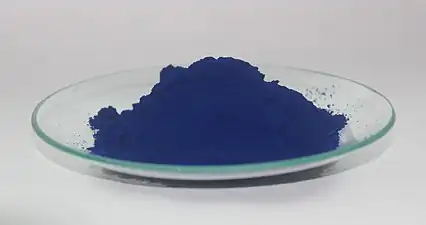

Ukiyo-e artists often made both prints and paintings; some specialized in one or the other.[167] In contrast with previous traditions, ukiyo-e painters favoured bright, sharp colours,[168] and often delineated contours with sumi ink, an effect similar to the linework in prints.[169] Unrestricted by the technical limitations of printing, a wider range of techniques, pigments, and surfaces were available to the painter.[170] Artists painted with pigments made from mineral or organic substances, such as safflower, ground shells, lead, and cinnabar,[171] and later synthetic dyes imported from the West such as Paris green and Prussian blue.[172] Silk or paper kakemono hanging scrolls, makimono handscrolls, or byōbu folding screens were the most common surfaces.[167]

- Ukiyo-e paintings

Bijin-gaKaigetsudō Ando, 18th century

Bijin-gaKaigetsudō Ando, 18th century A Winter PartyUtagawa Toyoharu, mid-18th – late 19th century

A Winter PartyUtagawa Toyoharu, mid-18th – late 19th century_Yoshiwara_no_Hana.jpg.webp) Yoshiwara no HanaUtamaro, c. 1788–91

Yoshiwara no HanaUtamaro, c. 1788–91 Feminine WaveHokusai, mid-19th century

Feminine WaveHokusai, mid-19th century

Print production

_key_block_face_b.jpg.webp)

Ukiyo-e prints were the works of teams of artisans in several workshops;[173] it was rare for designers to cut their own woodblocks.[174] Labour was divided into four groups: the publisher, who commissioned, promoted, and distributed the prints; the artists, who provided the design image; the woodcarvers, who prepared the woodblocks for printing; and the printers, who made impressions of the woodblocks on paper.[175] Normally only the names of the artist and publisher were credited on the finished print.[176]

Ukiyo-e prints were impressed on hand-made paper[177] manually, rather than by mechanical press as in the West.[178] The artist provided an ink drawing on thin paper, which was pasted[179] to a block of cherry wood[lower-alpha 9] and rubbed with oil until the upper layers of paper could be pulled away, leaving a translucent layer of paper that the block-cutter could use as a guide. The block-cutter cut away the non-black areas of the image, leaving raised areas that were inked to leave an impression.[173] The original drawing was destroyed in the process.[179]

Prints were made with blocks face up so the printer could vary pressure for different effects, and watch as paper absorbed the water-based sumi ink,[178] applied quickly in even horizontal strokes.[182] Amongst the printer's tricks were embossing of the image, achieved by pressing an uninked woodblock on the paper to achieve effects, such as the textures of clothing patterns or fishing net.[183] Other effects included burnishing[184] rubbing the paper with agate to brighten colours;[185] varnishing; overprinting; dusting with metal or mica; and sprays to imitate falling snow.[184]

The ukiyo-e print was a commercial art form, and the publisher played an important role.[186] Publishing was highly competitive; over a thousand publishers are known from throughout the period. The number peaked at around 250 in the 1840s and 1850s[187]—200 in Edo alone[188]—and slowly shrank following the opening of Japan until about 40 remained at the opening of the 20th century. The publishers owned the woodblocks and copyrights, and from the late 18th century enforced copyrights[187] through the Picture Book and Print Publishers Guild.[lower-alpha 10][189][189] Prints that went through several pressings were particularly profitable, as the publisher could reuse the woodblocks without further payment to the artist or woodblock cutter. The woodblocks were also traded or sold to other publishers or pawnshops.[190] Publishers were usually also vendors, and commonly sold each other's wares in their shops.[189] In addition to the artist's seal, publishers marked the prints with their own seals—some a simple logo, others quite elaborate, incorporating an address or other information.[191]

Print designers went through apprenticeship before being granted the right to produce prints of their own that they could sign with their own names.[192] Young designers could be expected to cover part or all of the costs of cutting the woodblocks. As the artists gained fame, publishers usually covered these costs, and artists could demand higher fees.[193]

In pre-modern Japan, people could go by numerous names throughout their lives, their childhood yōmyō personal name different from their zokumyō name as an adult. An artist's name consisted of a gasei—an artist surname—followed by an azana personal art name. The gasei was most frequently taken from the school the artist belonged to, such as Utagawa or Torii,[194] and the azana normally took a Chinese character from the master's art name—for example, many students of Toyokuni (豊国) took the "kuni" (国) from his name, including Kunisada (国貞) and Kuniyoshi (国芳).[192] The names artists signed to their works can be a source of confusion as they sometimes changed names through their careers;[195] Hokusai was an extreme case, using over a hundred names throughout his 70-year career.[196]

The prints were mass-marketed,[186] and by the mid-19th century, the total circulation of a print could run into the thousands.[197] Retailers and travelling sellers promoted them at prices affordable to prosperous townspeople.[198] In some cases, the prints advertised kimono designs by the print artist.[186] From the second half of the 17th century, prints were frequently marketed as part of a series,[191] each print stamped with the series name and the print's number in that series.[199] This proved a successful marketing technique, as collectors bought each new print in the series to keep their collections complete.[191] By the 19th century, series such as Hiroshige's Fifty-three Stations of the Tōkaidō ran to dozens of prints.[199]

- Making ukiyo-e prints

_Making_Prints.jpg.webp) Making Prints, Hosoki Toshikazu, 1879

Making Prints, Hosoki Toshikazu, 1879_Imay%C5%8D_mitate_shin%C5%8D_k%C5%8Dsh%C5%8D_yori_shokunin.jpg.webp) The woodblock printing process, Kunisada, 1857. A fantasy version, wholly staffed by well-dressed "beauties". In fact, few women worked in printmaking;[200] Hokusai's daughter Katsushika Ōi was one.

The woodblock printing process, Kunisada, 1857. A fantasy version, wholly staffed by well-dressed "beauties". In fact, few women worked in printmaking;[200] Hokusai's daughter Katsushika Ōi was one.

Colour print production

While colour printing in Japan dates to the 1640s, early ukiyo-e prints used only black ink. Colour was sometimes added by hand, using a red lead ink in tan-e prints, or later in a pink safflower ink in beni-e prints. Colour printing arrived in books in the 1720s and in single-sheet prints in the 1740s, with a different block and printing for each colour. Early colours were limited to pink and green; techniques expanded over the following two decades to allow up to five colours.[173] The mid-1760s brought full-colour nishiki-e prints[173] made from ten or more woodblocks.[201] To keep the blocks for each colour aligned correctly, registration marks called kentō were placed on one corner and an adjacent side.[173]

Printers first used natural colour dyes made from mineral or vegetable sources. The dyes had a translucent quality that allowed a variety of colours to be mixed from primary red, blue, and yellow pigments.[202] In the 18th century, Prussian blue became popular, and was particularly prominent in the landscapes of Hokusai and Hiroshige,[202] as was bokashi, where the printer produced gradations of colour or blended one colour into another.[203] Cheaper and more consistent synthetic aniline dyes arrived from the West in 1864. The colours were harsher and brighter than traditional pigments. The Meiji government promoted their use as part of broader policies of Westernization.[204]

Criticism and historiography

Contemporary records of ukiyo-e artists are rare. The most significant is the Ukiyo-e Ruikō ("Various Thoughts on ukiyo-e"), a collection of commentaries and artist biographies. Ōta Nanpo compiled the first, no-longer-extant version around 1790. The work did not see print during the Edo era, but circulated in hand-copied editions that were subject to numerous additions and alterations;[205] over 120 variants of the Ukiyo-e Ruikō are known.[206]

Before World War II, the predominant view of ukiyo-e stressed the centrality of prints; this viewpoint ascribes ukiyo-e's founding to Moronobu. Following the war, thinking turned to the importance of ukiyo-e painting and making direct connections with 17th century Yamato-e paintings; this viewpoint sees Matabei as the genre's originator, and is especially favoured in Japan. This view had become widespread among Japanese researchers by the 1930s, but the militaristic government of the time suppressed it, wanting to emphasize a division between the Yamato-e scroll paintings associated with the court, and the prints associated with the sometimes anti-authoritarian merchant class.[19]

The earliest comprehensive historical and critical works on ukiyo-e came from the West. Ernest Fenollosa was Professor of Philosophy at the Imperial University in Tokyo from 1878, and was Commissioner of Fine Arts to the Japanese government from 1886. His Masters of Ukioye of 1896 was the first comprehensive overview and set the stage for most later works with an approach to the history in terms of epochs: beginning with Matabei in a primitive age, it evolved towards a late-18th century golden age that began to decline with the advent of Utamaro, and had a brief revival with Hokusai and Hiroshige's landscapes in the 1830s.[207] Laurence Binyon, the Keeper of Oriental Prints and Drawings at the British Museum, wrote an account in Painting in the Far East in 1908 that was similar to Fenollosa's, but placed Utamaro and Sharaku amongst the masters. Arthur Davison Ficke built on the works of Fenollosa and Binyon with a more comprehensive Chats on Japanese Prints in 1915.[208] James A. Michener's The Floating World in 1954 broadly followed the chronologies of the earlier works, while dropping classifications into periods and recognizing the earlier artists not as primitives but as accomplished masters emerging from earlier painting traditions.[209] For Michener and his sometime collaborator Richard Lane, ukiyo-e began with Moronobu rather than Matabei.[210] Lane's Masters of the Japanese Print of 1962 maintained the approach of period divisions while placing ukiyo-e firmly within the genealogy of Japanese art. The book acknowledges artists such as Yoshitoshi and Kiyochika as late masters.[211]

Seiichirō Takahashi's Traditional Woodblock Prints of Japan of 1964 placed ukiyo-e artists in three periods: the first was a primitive period that included Harunobu, followed by a golden age of Kiyonaga, Utamaro, and Sharaku, and then a closing period of decline following the declaration beginning in the 1790s of strict sumptuary laws that dictated what could be depicted in artworks. The book nevertheless recognizes a larger number of masters from throughout this last period than earlier works had,[212] and viewed ukiyo-e painting as a revival of Yamato-e painting.[17] Tadashi Kobayashi further refined Takahashi's analysis by identifying the decline as coinciding with the desperate attempts of the shogunate to hold on to power through the passing of draconian laws as its hold on the country continued to break down, culminating in the Meiji Restoration in 1868.[213]

Ukiyo-e scholarship has tended to focus on the cataloguing of artists, an approach that lacks the rigour and originality that has come to be applied to art analysis in other areas. Such catalogues are numerous, but tend overwhelmingly to concentrate on a group of recognized geniuses. Little original research has been added to the early, foundational evaluations of ukiyo-e and its artists, especially with regard to relatively minor artists.[214] While the commercial nature of ukiyo-e has always been acknowledged, evaluation of artists and their works has rested on the aesthetic preferences of connoisseurs and paid little heed to contemporary commercial success.[215]

Standards for inclusion in the ukiyo-e canon rapidly evolved in the early literature. Utamaro was particularly contentious, seen by Fenollosa and others as a degenerate symbol of ukiyo-e's decline; Utamaro has since gained general acceptance as one of the form's greatest masters. Artists of the 19th century such as Yoshitoshi were ignored or marginalized, attracting scholarly attention only towards the end of the 20th century.[216] Works on late-era Utagawa artists such as Kunisada and Kuniyoshi have revived some of the contemporary esteem these artists enjoyed. Many late works examine the social or other conditions behind the art, and are unconcerned with valuations that would place it in a period of decline.[217]

Novelist Jun'ichirō Tanizaki was critical of the superior attitude of Westerners who claimed a higher aestheticism in purporting to have discovered ukiyo-e. He maintained that ukiyo-e was merely the easiest form of Japanese art to understand from the perspective of Westerners' values, and that Japanese of all social strata enjoyed ukiyo-e, but that Confucian morals of the time kept them from freely discussing it, social mores that were violated by the West's flaunting of the discovery.[218]

[[File:Tagosaku to Mokube no Tokyo Kenbutsu.jpg|thumb|left|alt=Black-and-white comic strip in Japanese|Manga histories often find an ancestor in the Hokusai Manga.

Rakuten Kitazawa, Tagosaku to Mokube no Tōkyō Kenbutsu,{{efn|Tagosaku to Mokube no Tokyo Kenbutsu (田吾作と杢兵衛の東京見物, Tagosaku and Mokube Sightseeing in Tokyo), 1902]]

Since the dawn of the 20th century historians of manga—Japanese comics and cartooning—have developed narratives connecting the art form to pre-20th century Japanese art. Particular emphasis falls on the Hokusai Manga as a precursor, though Hokusai's book is not narrative, nor does the term "manga" originate with Hokusai.[219] In English and other languages, the word "manga" is used in the restrictive sense of "Japanese comics" or "Japanese-style comics",[220] while in Japanese it indicates all forms of comics, cartooning,[221] and caricature.[222]

Collection and preservation

The ruling classes strictly limited the space permitted for the homes of the lower social classes; the relatively small size of ukiyo-e works was ideal for hanging in these homes.[223] Little record of the patrons of ukiyo-e paintings has survived. They sold for considerably higher prices than prints—up to many thousands of times more, and thus must have been purchased by the wealthy, likely merchants and perhaps some from the samurai class.[10] Late-era prints are the most numerous extant examples, as they were produced in the greatest quantities in the 19th century, and the older a print is the less chance it had of surviving.[224] Ukiyo-e was largely associated with Edo, and visitors to Edo often bought what they called azuma-e[lower-alpha 11] as souvenirs. Shops that sold them might specialize in products such as hand-held fans, or offer a diverse selection.[189]

The ukiyo-e print market was highly diversified as it sold to a heterogeneous public, from dayworkers to wealthy merchants.[225] Little concrete information is known about production and consumption habits. Detailed records in Edo were kept of a wide variety of courtesans, actors, and sumo wrestlers, but no such records pertaining to ukiyo-e remain—or perhaps ever existed. Determining what is understood about the demographics of ukiyo-e consumption has required indirect means.[226]

Determining at what prices prints sold is a challenge for experts, as records of hard figures are scanty and there was great variety in the production quality, size,[227] supply and demand,[228] and methods, which went through changes such as the introduction of full-colour printing.[229] How expensive prices can be considered is also difficult to determine as social and economic conditions were in flux throughout the period.[230] In the 19th century, records survive of prints selling from as low as 16 mon[231] to 100 mon for deluxe editions.[232] Jun'ichi Ōkubo suggests that prices in the 1920s and 1930s of mon were likely common for standard prints.[233] As a loose comparison, a bowl of soba noodles in the early 19th century typically sold for 16 mon.[234]

The dyes in ukiyo-e prints are susceptible to fading when exposed even to low levels of light; this makes long-term display undesirable. The paper they are printed on deteriorates when it comes in contact with acidic materials, so storage boxes, folders, and mounts must be of neutral pH or alkaline. Prints should be regularly inspected for problems needing treatment, and stored at a relative humidity of 70% or less to prevent fungal discolourations.[235]

The paper and pigments in ukiyo-e paintings are sensitive to light and seasonal changes in humidity. Mounts must be flexible, as the sheets can tear under sharp changes in humidity. In the Edo era, the sheets were mounted on long-fibred paper and preserved scrolled up in plain paulownia wood boxes placed in another lacquer wooden box.[236] In museum settings, display times are heavily limited to prevent deterioration from exposure to light and environmental pollution, and care is taken in the unrolling and rerolling of scrolls, with scrolling causing concavities in the paper, and the unrolling and rerolling of the scrolls causing creasing.[237] The humidity levels that scrolls are kept in are generally between 50 percent and 60 percent, as scrolls kept in too dry an atmosphere become brittle.[238]

Because ukiyo-e prints were mass-produced, collecting them presents considerations different from the collecting of paintings. There is wide variation in the condition, rarity, cost, and quality of extant prints. Prints may have stains, foxing, wormholes, tears, creases, or dogmarks, the colours may have faded, or they may have been retouched. Carvers may have altered the colours or composition of prints that went through multiple editions. When cut after printing, the paper may have been trimmed within the margin.[239] Values of prints depend on a variety of factors, including the artist's reputation, print condition, rarity, and whether it is an original pressing—even high-quality later printings will fetch a fraction of the valuation of an original.[240]

Ukiyo-e prints often went through multiple editions, sometimes with changes made to the blocks in later editions. Editions made from recut woodblocks also circulate, such as legitimate later reproductions, as well as pirate editions and other fakes.[241] Takamizawa Enji (1870–1927), a producer of ukiyo-e reproductions, developed a method of recutting woodblocks to print fresh colour on faded originals, over which he used tobacco ash to make the fresh ink seem aged. These refreshed prints he resold as original printings.[242] Amongst the defrauded collectors was American architect Frank Lloyd Wright, who brought 1500 Takamizawa prints with him from Japan to the US, some of which he had sold before the truth was discovered.[243]

Ukiyo-e artists are referred to in the Japanese style, the surname preceding the personal name, and well-known artists such as Utamaro and Hokusai by personal name alone.[244] Dealers normally refer to ukiyo-e prints by the names of the standard sizes, most commonly the 34.5-by-22.5-centimetre (13.6 in × 8.9 in) aiban, the 22.5-by-19-centimetre (8.9 in × 7.5 in) chūban, and the 38-by-23-centimetre (15.0 in × 9.1 in) ōban[203]—precise sizes vary, and paper was often trimmed after printing.[245]

Many of the largest high-quality collections of ukiyo-e lie outside Japan.[246] Examples entered the collection of the National Library of France in the first half of the 19th century. The British Museum began a collection in 1860[247] that by the late 20th century numbered 70000 items.[248] The largest, surpassing 100000 items, resides in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston,[246] begun when Ernest Fenollosa donated his collection in 1912.[249] The first exhibition in Japan of ukiyo-e prints was likely one presented by Kōjirō Matsukata in 1925, who amassed his collection in Paris during World War I and later donated it to the National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo.[250] The largest collection of ukiyo-e in Japan is the 100000 pieces in the Japan Ukiyo-e Museum in the city of Matsumoto.[251]

See also

Notes

- ↑ The obsolete transliteration "ukiyo-ye" appears in older texts.

- ↑ Many of these type pieces were repeat characters; as certain characters were used multiple times on the same page, multiples of these characters needed to be available to the printer.

- ↑ tan (丹): a pigment made from red lead mixed with sulphur and saltpetre[32]

- ↑ beni (紅): a pigment produced from safflower petals.[34]

- ↑ Torii Kiyotada is said to have made the first uki-e;[36] Masanobu advertised himself as its innovator.[37]A Layman's Explanation of the Rules of Drawing with a Compass and Ruler introduced Western-style geometrical perspective drawing to Japan in the 1734, based on a Dutch text of 1644 (see Rangaku, "Dutch learning" during the Edo period); Chinese texts on the subject also appeared during the decade.[36]Okumura likely learned about geometrical perspective from Chinese sources, some of which bear a striking resemblance to Okumura's works.[38]

- ↑ Until 1873 the Japanese calendar was lunisolar, and each year the Japanese New Year fell on different days of the Gregorian calendar's January or February.

- ↑ Burty coined the term le Japonisme in French in 1872.[103]

- ↑ jatai shisei (蛇体姿勢, "serpentine posture")

- ↑ Traditional Japanese woodblocks were cut along the grain, as opposed to the blocks of Western wood engraving, which were cut across the grain. In both methods, the dimensions of the woodblock was limited by the girth of the tree.[180] In the 20th century, plywood became the material of choice for Japanese woodcarvers, as it is cheaper, easier to carve, and less limited in size.[181]

- ↑ Jihon Toiya (地本問屋, "Picture Book and Print Publishers Guild")[189]

- ↑ azuma-e (東絵, "pictures of the Eastern capital")

References

- ↑ Lane 1962, pp. 8–9.

- 1 2 Kobayashi 1997, p. 66.

- ↑ Kobayashi 1997, pp. 66–67.

- ↑ Kobayashi 1997, pp. 67–68.

- 1 2 Kita 1984, pp. 252–253.

- 1 2 3 Penkoff 1964, pp. 4–5.

- ↑ Marks 2012, p. 17.

- ↑ Singer 1986, p. 66.

- ↑ Penkoff 1964, p. 6.

- 1 2 Bell 2004, p. 137.

- 1 2 Kobayashi 1997, p. 68.

- 1 2 3 Harris 2011, p. 37.

- ↑ Kobayashi 1997, p. 69.

- ↑ Kobayashi 1997, pp. 69–70.

- ↑ Hickman 1978, pp. 5–6.

- 1 2 3 Kikuchi & Kenny 1969, p. 31.

- 1 2 Kita 2011, p. 155.

- ↑ Kita 1999, p. 39.

- 1 2 Kita 2011, pp. 149, 154–155.

- ↑ Kita 1999, pp. 44–45.

- ↑ Yashiro 1958, pp. 216, 218.

- ↑ Kobayashi 1997, pp. 70–71.

- ↑ Kobayashi 1997, pp. 71–72.

- ↑ Kobayashi 1997, p. 71.

- ↑ Kobayashi 1997, pp. 72–73.

- ↑ Kobayashi 1997, pp. 72–74.

- 1 2 Kobayashi 1997, pp. 75–76.

- ↑ Kobayashi 1997, pp. 74–75.

- 1 2 Noma 1966, p. 188.

- ↑ Hibbett 2001, p. 69.

- ↑ Munsterberg 1957, p. 154.

- ↑ Kobayashi 1997, p. 76.

- ↑ Kobayashi 1997, pp. 76–77.

- 1 2 3 Kobayashi 1997, p. 77.

- ↑ Penkoff 1964, p. 16.

- 1 2 3 King 2010, p. 47.

- ↑ Kobayashi 1997, p. 78.

- ↑ Suwa 1998, pp. 64–68.

- ↑ Suwa 1998, p. 64.

- ↑ Kobayashi 1997, pp. 77–79.

- ↑ Kobayashi 1997, pp. 80–81.

- ↑ Kobayashi 1997, p. 82.

- ↑ Lane 1962, pp. 150, 152.

- ↑ Kobayashi 1997, p. 81.

- 1 2 Michener 1959, p. 89.

- 1 2 Munsterberg 1957, p. 155.

- ↑ Kobayashi 1997, pp. 82–83.

- ↑ Kobayashi 1997, p. 83.

- ↑ Kobayashi 1997, pp. 84–85.

- ↑ Hockley 2003, p. 3.

- 1 2 3 Kobayashi 1997, p. 85.

- ↑ Marks 2012, p. 68.

- ↑ Stewart 1922, p. 224; Neuer, Libertson & Yoshida 1990, p. 259.

- ↑ Thompson 1986, p. 44.

- ↑ Salter 2006, p. 204.

- ↑ Bell 2004, p. 105.

- ↑ Neuer, Libertson & Yoshida 1990, p. 145.

- 1 2 3 4 Kobayashi 1997, p. 91.

- ↑ Kobayashi 1997, pp. 85–86.

- ↑ Kobayashi 1997, p. 87.

- ↑ Michener 1954, p. 231.

- 1 2 Lane 1962, p. 224.

- ↑ Kobayashi 1997, pp. 87–88.

- ↑ Kobayashi 1997, p. 88.

- ↑ Kobayashi 1997, pp. 88–89.

- 1 2 3 4 Neuer, Libertson & Yoshida 1990, p. 40.

- 1 2 Kobayashi 1997, pp. 91–92.

- ↑ Kobayashi 1997, pp. 89–91.

- ↑ Neuer, Libertson & Yoshida 1990, pp. 40–41.

- ↑ Harris 2011, p. 38.

- ↑ Salter 2001, pp. 12–13.

- ↑ Winegrad 2007, pp. 18–19.

- 1 2 Harris 2011, p. 132.

- 1 2 Michener 1959, p. 175.

- ↑ Michener 1959, pp. 176–177.

- ↑ Kobayashi 1997, pp. 92–93.

- ↑ Lewis & Lewis 2008, p. 385; Honour & Fleming 2005, p. 709; Benfey 2007, p. 17; Addiss, Groemer & Rimer 2006, p. 146; Buser 2006, p. 168.

- ↑ Lewis & Lewis 2008, p. 385; Belloli 1999, p. 98.

- ↑ Munsterberg 1957, p. 158.

- ↑ King 2010, pp. 84–85.

- ↑ Lane 1962, pp. 284–285.

- 1 2 Lane 1962, p. 290.

- 1 2 Lane 1962, p. 285.

- ↑ Harris 2011, pp. 153–154.

- ↑ Kobayashi 1997, pp. 94–95.

- ↑ Munsterberg 1957, pp. 158–159.

- ↑ King 2010, p. 116.

- 1 2 Michener 1959, p. 200.

- ↑ Michener 1959, p. 200; Kobayashi 1997, p. 95.

- ↑ Kobayashi 1997, p. 95; Faulkner & Robinson 1999, pp. 22–23; Kobayashi 1997, p. 95; Michener 1959, p. 200.

- ↑ Seton 2010, p. 71.

- 1 2 Seton 2010, p. 69.

- ↑ Harris 2011, p. 153.

- ↑ Meech-Pekarik 1986, pp. 125–126.

- 1 2 3 4 Watanabe 1984, p. 667.

- ↑ Neuer, Libertson & Yoshida 1990, p. 48.

- 1 2 Harris 2011, p. 163.

- 1 2 Meech-Pekarik 1982, p. 93.

- ↑ Watanabe 1984, pp. 680–681.

- ↑ Watanabe 1984, p. 675.

- ↑ Salter 2001, p. 12.

- ↑ Weisberg, Rakusin & Rakusin 1986, p. 7.

- 1 2 Weisberg 1975, p. 120.

- ↑ Jobling & Crowley 1996, p. 89.

- ↑ Meech-Pekarik 1982, p. 96.

- ↑ Weisberg, Rakusin & Rakusin 1986, p. 6.

- ↑ Jobling & Crowley 1996, p. 90.

- ↑ Meech-Pekarik 1982, pp. 101–103.

- ↑ Meech-Pekarik 1982, pp. 96–97.

- ↑ Merritt 1990, p. 15.

- 1 2 Mansfield 2009, p. 134.

- ↑ Ives 1974, p. 17.

- ↑ Sullivan 1989, p. 230.

- ↑ Ives 1974, p. 37–39, 45.

- ↑ Jobling & Crowley 1996, pp. 90–91.

- 1 2 Ives 1974, p. 80.

- ↑ Meech-Pekarik 1982, p. 99.

- ↑ Ives 1974, p. 96.

- ↑ Ives 1974, p. 56.

- ↑ Ives 1974, p. 67.

- ↑ Gerstle & Milner 1995, p. 70.

- ↑ Hughes 1960, p. 213.

- ↑ King 2010, pp. 119, 121.

- 1 2 Seton 2010, p. 81.

- ↑ Brown 2006, p. 22; Seton 2010, p. 81.

- ↑ Brown 2006, p. 23; Seton 2010, p. 81.

- ↑ Brown 2006, p. 21.

- ↑ Merritt 1990, p. 109.

- 1 2 Munsterberg 1957, p. 181.

- ↑ Statler 1959, p. 39.

- ↑ Statler 1959, pp. 35–38.

- ↑ Fiorillo 1999.

- ↑ Penkoff 1964, pp. 9–11.

- ↑ Lane 1962, p. 9.

- ↑ Bell 2004, p. xiv; Michener 1959, p. 11.

- ↑ Michener 1959, pp. 11–12.

- 1 2 Michener 1959, p. 90.

- ↑ Bell 2004, p. xvi.

- ↑ Sims 1998, p. 298.

- 1 2 Bell 2004, p. 34.

- ↑ Bell 2004, pp. 50–52.

- ↑ Bell 2004, pp. 53–54.

- ↑ Bell 2004, p. 66.

- ↑ Suwa 1998, pp. 57–60.

- ↑ Suwa 1998, pp. 62–63.

- ↑ Suwa 1998, pp. 106–107.

- ↑ Suwa 1998, pp. 108–109.

- ↑ Suwa 1998, pp. 101–106.

- ↑ Harris 2011, p. 60.

- ↑ Hillier 1954, p. 20.

- ↑ Harris 2011, pp. 95, 98.

- ↑ Harris 2011, p. 41.

- ↑ Harris 2011, pp. 38, 41.

- ↑ Harris 2011, pp. 124.

- ↑ Seton 2010, p. 64; Harris 2011.

- ↑ Seton 2010, p. 64.

- 1 2 Screech 1999, p. 15.

- ↑ Harris 2011, pp. 128.

- ↑ Harris 2011, p. 134.

- 1 2 3 Harris 2011, p. 146.

- ↑ Harris 2011, pp. 155–156.

- ↑ Harris 2011, pp. 148, 153.

- ↑ Harris 2011, p. 163–164.

- ↑ Harris 2011, p. 166–167.

- ↑ Harris 2011, p. 170.

- ↑ King 2010, p. 111.

- 1 2 Fitzhugh 1979, p. 27.

- ↑ Bell 2004, p. xii.

- ↑ Bell 2004, p. 236.

- ↑ Bell 2004, p. 235–236.

- ↑ Fitzhugh 1979, pp. 29, 34.

- ↑ Fitzhugh 1979, pp. 35–36.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Faulkner & Robinson 1999, p. 27.

- ↑ Penkoff 1964, p. 21.

- ↑ Salter 2001, p. 11.

- ↑ Salter 2001, p. 61.

- ↑ Michener 1959, p. 11.

- 1 2 Penkoff 1964, p. 1.

- 1 2 Salter 2001, p. 64.

- ↑ Statler 1959, pp. 34–35.

- ↑ Statler 1959, p. 64; Salter 2001.

- ↑ Bell 2004, p. 225.

- ↑ Bell 2004, p. 246.

- 1 2 Bell 2004, p. 247.

- ↑ Frédéric 2002, p. 884.

- 1 2 3 Harris 2011, p. 62.

- 1 2 Marks 2012, p. 180.

- ↑ Salter 2006, p. 19.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Marks 2012, p. 10.

- ↑ Marks 2012, p. 18.

- 1 2 3 Marks 2012, p. 21.

- 1 2 Marks 2012, p. 13.

- ↑ Marks 2012, pp. 13–14.

- ↑ Marks 2012, p. 22.

- ↑ Merritt 1990, pp. ix–x.

- ↑ Link & Takahashi 1977, p. 32.

- ↑ Ōkubo 2008, pp. 153–154.

- ↑ Harris 2011, p. 62; Meech-Pekarik 1982, p. 93.

- 1 2 King 2010, pp. 48–49.

- ↑ "'Japanesque" sheds light on two worlds", The Mercury New, by Jennifer Modenessi, 14 October 2010

- ↑ Ishizawa & Tanaka 1986, p. 38; Merritt 1990, p. 18.

- 1 2 Harris 2011, p. 26.

- 1 2 Harris 2011, p. 31.

- ↑ Bell 2004, p. 234.

- ↑ Takeuchi 2004, pp. 118, 120.

- ↑ Tanaka 1999, p. 190.

- ↑ Bell 2004, pp. 3–5.

- ↑ Bell 2004, pp. 8–10.

- ↑ Bell 2004, p. 12.

- ↑ Bell 2004, p. 20.

- ↑ Bell 2004, pp. 13–14.

- ↑ Bell 2004, pp. 14–15.

- ↑ Bell 2004, pp. 15–16.

- ↑ Hockley 2003, pp. 13–14.

- ↑ Hockley 2003, pp. 5–6.

- ↑ Bell 2004, pp. 17–18.

- ↑ Bell 2004, pp. 19–20.

- ↑ Yoshimoto 2003, p. 65–66.

- ↑ Stewart 2014, pp. 28–29.

- ↑ Stewart 2014, p. 30.

- ↑ Johnson-Woods 2010, p. 336.

- ↑ Morita 2010, p. 33.

- ↑ Bell 2004, pp. 140, 175.

- ↑ Kita 2011, p. 149.

- ↑ Bell 2004, p. 140.

- ↑ Hockley 2003, pp. 7–8.

- ↑ Kobayashi & Ōkubo 1994, p. 216.

- ↑ Ōkubo 2013, p. 31.

- ↑ Ōkubo 2013, p. 32.

- ↑ Kobayashi & Ōkubo 1994, pp. 216–217.

- ↑ Ōkubo 2008, pp. 151–153.

- ↑ Kobayashi & Ōkubo 1994, p. 217.

- ↑ Ōkubo 2013, p. 43.

- ↑ Kobayashi & Ōkubo 1994, p. 217; Bell 2004, p. 174.

- ↑ Fiorillo 1999–2001.

- ↑ Fleming 1985, p. 61.

- ↑ Fleming 1985, p. 75.

- ↑ Toishi 1979, p. 25.

- ↑ Harris 2011, p. 180, 183–184.

- ↑ Fiorillo 2001–2002a.

- ↑ Fiorillo 1999–2005.

- ↑ Merritt 1990, p. 36.

- ↑ Fiorillo 2001–2002b.

- ↑ Lane 1962, p. 313.

- ↑ Faulkner & Robinson 1999, p. 40.

- 1 2 Merritt 1990, p. 13.

- ↑ Bell 2004, p. 38.

- ↑ Merritt 1990, pp. 13–14.

- ↑ Bell 2004, p. 39.

- ↑ Checkland 2004, p. 107.

- ↑ Garson 2001, p. 14.

Bibliography

Academic journals

- Fitzhugh, Elisabeth West (1979). "A Pigment Census of Ukiyo-E Paintings in the Freer Gallery of Art". Ars Orientalis. Freer Gallery of Art, The Smithsonian Institution and Department of the History of Art, University of Michigan. 11: 27–38. JSTOR 4629295.

- Fleming, Stuart (November–December 1985). "Ukiyo-e Painting: An Art Tradition under Stress". Archaeology. Archaeological Institute of America. 38 (6): 60–61, 75. JSTOR 41730275.

- Hickman, Money L. (1978). "Views of the Floating World". MFA Bulletin. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. 76: 4–33. JSTOR 4171617.

- Meech-Pekarik, Julia (1982). "Early Collectors of Japanese Prints and the Metropolitan Museum of Art". Metropolitan Museum Journal. University of Chicago Press. 17: 93–118. doi:10.2307/1512790. JSTOR 1512790. S2CID 193121981.

- Kita, Sandy (September 1984). "An Illustration of the Ise Monogatari: Matabei and the Two Worlds of Ukiyo". The Bulletin of the Cleveland Museum of Art. Cleveland Museum of Art. 71 (7): 252–267. JSTOR 25159874.

- Singer, Robert T. (March–April 1986). "Japanese Painting of the Edo Period". Archaeology. Archaeological Institute of America. 39 (2): 64–67. JSTOR 41731745.

- Tanaka, Hidemichi (1999). "Sharaku Is Hokusai: On Warrior Prints and Shunrô's (Hokusai's) Actor Prints". Artibus et Historiae. IRSA s.c. 20 (39): 157–190. doi:10.2307/1483579. JSTOR 1483579.

- Thompson, Sarah (Winter–Spring 1986). "The World of Japanese Prints". Philadelphia Museum of Art Bulletin. Philadelphia Museum of Art. 82 (349/350, The World of Japanese Prints): 1, 3–47. JSTOR 3795440.

- Toishi, Kenzō (1979). "The Scroll Painting". Ars Orientalis. Freer Gallery of Art, The Smithsonian Institution and Department of the History of Art, University of Michigan. 11: 15–25. JSTOR 4629294.

- Watanabe, Toshio (1984). "The Western Image of Japanese Art in the Late Edo Period". Modern Asian Studies. Cambridge University Press. 18 (4): 667–684. doi:10.1017/s0026749x00016371. JSTOR 312343. S2CID 145105044.

- Weisberg, Gabriel P. (April 1975). "Aspects of Japonisme". The Bulletin of the Cleveland Museum of Art. Cleveland Museum of Art. 62 (4): 120–130. JSTOR 25152585.

- Weisberg, Gabriel P.; Rakusin, Muriel; Rakusin, Stanley (Spring 1986). "On Understanding Artistic Japan". The Journal of Decorative and Propaganda Arts. Florida International University Board of Trustees on behalf of The Wolfsonian-FIU. 1: 6–19. doi:10.2307/1503900. JSTOR 1503900.

Books

- Addiss, Stephen; Groemer, Gerald; Rimer, J. Thomas (2006). Traditional Japanese Arts And Culture: An Illustrated Sourcebook. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-2018-3.

- Bell, David (2004). Ukiyo-e Explained. Global Oriental. ISBN 978-1-901903-41-6.

- Belloli, Andrea P. A. (1999). Exploring World Art. Getty Publications. ISBN 978-0-89236-510-4.

- Benfey, Christopher (2007). The Great Wave: Gilded Age Misfits, Japanese Eccentrics, and the Opening of Old Japan. Random House. ISBN 978-0-307-43227-8.

- Brown, Kendall H. (2006). "Impressions of Japan: Print Interactions East and West". In Javid, Christine (ed.). Color Woodcut International: Japan, Britain, and America in the Early Twentieth Century. Chazen Museum of Art. pp. 13–29. ISBN 978-0-932900-64-7.

- Buser, Thomas (2006). Experiencing Art Around Us. Cengage Learning. ISBN 978-0-534-64114-6.

- Checkland, Olive (2004). Japan and Britain After 1859: Creating Cultural Bridges. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-203-22183-9.

- Faulkner, Rupert; Robinson, Basil William (1999). Masterpieces of Japanese Prints: Ukiyo-e from the Victoria and Albert Museum. Kodansha International. ISBN 978-4-7700-2387-2.

- Frédéric, Louis (2002). Japan Encyclopedia. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-01753-5.

- Garson, Alfred (2001). Suzuki Twinkles: An Intimate Portrait. Alfred Music. ISBN 978-1-4574-0504-4.

- Gerstle, C. Andrew; Milner, Anthony Crothers (1995). Recovering the Orient: Artists, Scholars, Appropriations. Psychology Press. ISBN 978-3-7186-5687-5.