An unconstitutional constitutional amendment is a concept in judicial review based on the idea that even a properly passed and properly ratified constitutional amendment, specifically one that is not explicitly prohibited by a constitution's text, can nevertheless be unconstitutional on substantive (as opposed to procedural) grounds—such as due to this amendment conflicting with some constitutional or even extra-constitutional norm, value, and/or principle.[1][2][3] As Israeli legal academic Yaniv Roznai's 2017 book Unconstitutional Constitutional Amendments: The Limits of Amendment Powers demonstrates, the unconstitutional constitutional amendment doctrine has been adopted by various courts and legal scholars in various countries throughout history.[1] While this doctrine has generally applied specifically to constitutional amendments, there have been moves and proposals to also apply this doctrine to original parts of a constitution.

Concept and Origination in the United States

Given that the Constitution of the United States is codified and there are no limits on amendments found within Article V (excluding the one remaining entrenched clause), the ability and willingness of the Supreme Court of the United States to overturn any constitutional amendment is questionable. No national constitutional amendment in the United States has ever been ruled unconstitutional by a court. Unlike the uncodified constitutions of many other countries, such as Israel and the United Kingdom, the codified US constitution sets high standards for amendments, but places no limits on the content of amendments. Additionally, amendments to the Constitution are extremely rare, with the last amendment to the Constitution (excluding amendments originally approved in the 18th century) being ratified in the 1970s. Nevertheless, some legal scholars support the possibility of unconstitutional amendments.

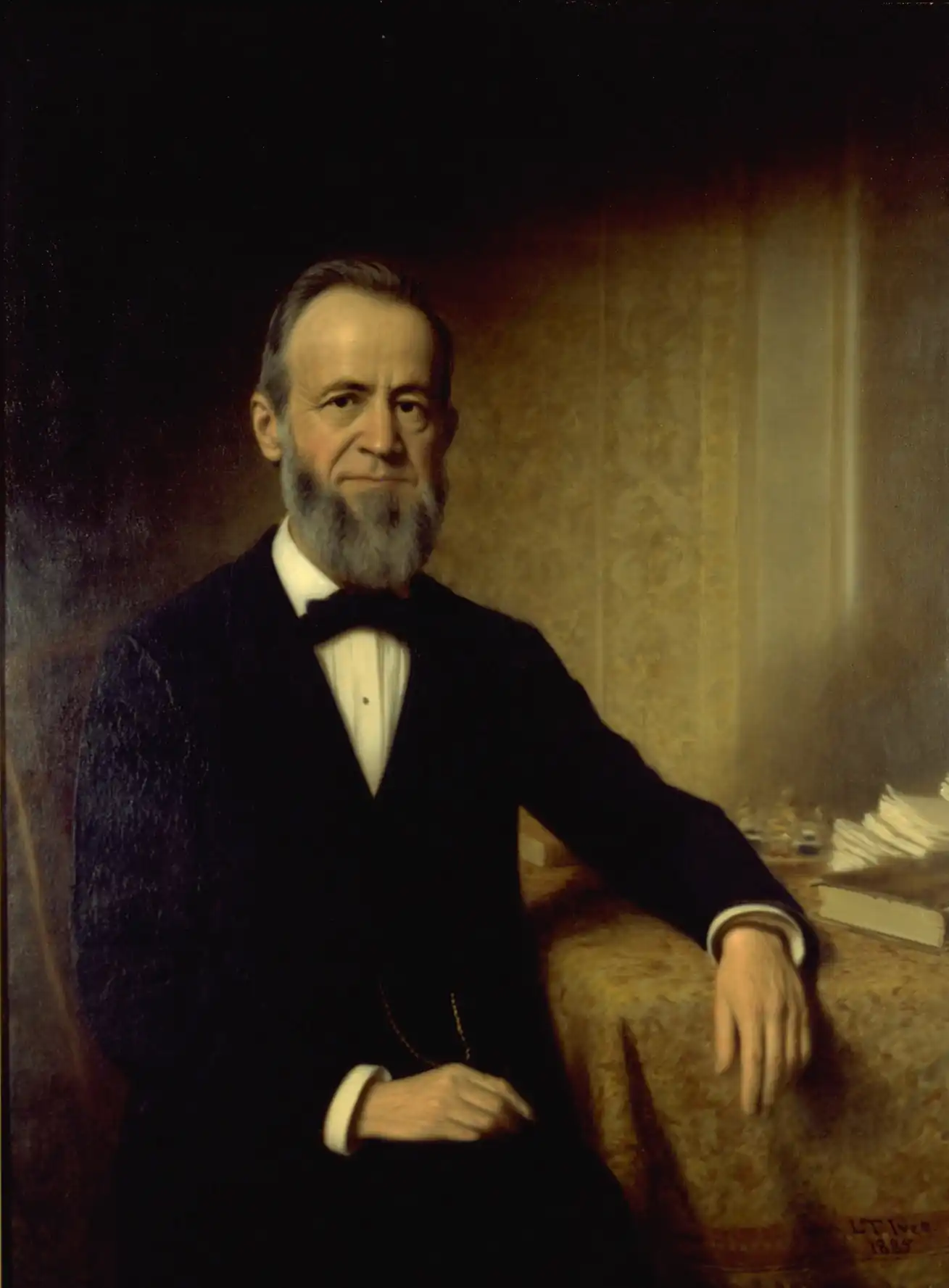

The idea of an unconstitutional constitutional amendment has been around since at least the 1890s—with it being embraced by former Michigan Supreme Court Chief Justice Thomas M. Cooley in 1893[4] and US law professor Arthur Machen in 1910 (in Machen's case, in arguing that the Fifteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution might be unconstitutional).[5] This theory is based on the idea that there is a difference between amending a particular constitution (in other words, the constitution-amending power or the secondary constituent power) and revising it to such an extent that it is essentially a new constitution (in other words, the constitution-making power or the primary constituent power)—with proponents of this idea viewing the former as being acceptable while viewing the latter as being unacceptable (even if the existing constitution doesn't actually explicitly prohibit doing the latter through its amendment process) unless the people actually adopt a new constitution using their constitution-making power.[6] Thomas M. Cooley insisted that amendments "cannot be revolutionary; they must be harmonious with the body of the instrument".[7] Elaborating on this point, Cooley argued that "an amendment converting a democratic republican government into an aristocracy or a monarchy would not be an amendment, but rather a revolution" that would require the creation and adoption of a new constitution even if the text of the existing constitution didn't actually prohibit such an amendment.[7]

In a 1991 law review article, United States law professor Richard George Wright argues that if a constitutional amendment leaves a constitution in such a state that it is a "smoldering, meaningless wreckage" and extremely internally inconsistent and incoherent, then such an amendment should indeed be declared unconstitutional.[6] Wright compares this to a scenario of a body rejecting a tissue transplant due to this transplant being extremely incompatible with the body to which it is grafted—thus triggering an immune response on the part of the body.[6] In Wright's analogy, the constitution is the body and the amendment is a tissue transplant and while both can peacefully exist separately, they cannot peacefully exist together.[6] While Wright rejects the idea that certain specific hypothetical amendments are unconstitutional (such as an amendment that abolishes one or more US states), Wright does agree with Yale law professor Akhil Amar's view that a hypothetical constitutional amendment that completely abolishes freedom of speech would be unconstitutional because such an amendment would also undermine many other US constitutional provisions and thus "leave standing only a disjointed, unworkably insufficient, fragmentary constitutional structure."[6] Such an amendment would not only conflict with the provisions of the US Constitution's First Amendment—such an override being in fact not unheard of—but also with an innumerable multitude of other US constitutional provisions.[6] Wright also agrees with US law professor Walter F. Murphy's view that a constitutional amendment that legally enshrines white supremacy, limits the franchise to whites, requires both US state governments and the US federal governments to segregate public institutions, and authorizes other legal disabilities that clearly offend and even deny the human dignity of non-whites would be unconstitutional because–in spite of such an amendment's compatibility with the pre-Civil War US Constitution–such an amendment "conflicts fundamentally and irreconcilably with virtually all conceptions of the commonly cited constitutional value of equality."[6]

In a 2015 article, Yaniv Roznai argues that the more that the expression of the secondary constituent power (as in, the constitution-amending power) resembles the expression of a democratic primary constituent power, the less that it should be bound by limitations (whether explicit or implicit), and vice versa–with the less that the secondary constituent power resembles the primary constituent power and the more that the secondary constituent power resembles an ordinary legislative power, the more that it should be bound by limitations (whether explicit or implicit).[8] A variation of this argument was also endorsed in 2013 by Carlos Bernal-Pulido.[9] Meanwhile, in a 2018 review of Yaniv Roznai's 2017 book about unconstitutional constitutional amendments, Joel Colón-Rios argued that the unconstitutional constitutional amendment doctrine should only apply in jurisdictions where the constitution-making process was indeed both strongly democratic and strongly inclusive–something that Colón-Rios pointed out is not actually true for the processes by which many currently existing constitutions were made and ratified.[10] In addition, Colón-Rios speculated as to whether the distinction between the primary constituent power and the secondary constituent power can actually be sustained at all in cases where the secondary constituent power is as democratic (as in, a genuine expression of the people's will) or even more democratic than the primary constituent power is–for instance, if an expression of the secondary constituent power involves the convocation of a democratic and inclusive constituent assembly or constitutional convention whereas an expression of the primary constituent power doesn't.[10] In the same article, Colón-Rios wondered whether jurisdictions with constitutions that lack a legal mechanism to resurrect the primary constituent power should categorically reject the unconstitutional constitutional amendment doctrine since the use and invocation of this doctrine in these jurisdictions would mean that certain constitutional principles there would only be capable of being changed or altered through revolution.[10]

In a 2018 review of Roznai's book, Adrienne Stone argues that there is a sound case that an amendment that transforms a constitution into some entity other than a constitution–for instance, by eliminating the rule of law–would be unconstitutional.[11] Otherwise, according to Stone, the concept of a constitution would lack any meaningful sense.[11] However, Stone is much more critical of Roznai's claim that constitutional changes that alter a constitution's identity while allowing it to remain a constitution–simply a different constitution from what it was when it was first created–are unconstitutional.[11] After all, Stone argues that a particular constitution's extreme malleability–and thus a particular constitution's rejection of the unconstitutional constitutional amendment doctrine–can itself be considered a part of this constitution's identity, thus making it improper for courts to alter it.[11] Stone also argues that the question of whether a constitutional amendment is indeed unconstitutional should not only be decided based on whether the constitution-amending process was democratic, inclusive, and deliberative, but also on whether the constitution-making process was as democratic, inclusive, and deliberative as the constitution-amending process was.[11] Stone uses her home country of Australia as an example where the constitution-amending process was more democratic and thus a better representation of the people's will than the constitution-making process was since at the time that Australia's constitution was written back in the 1890s, Australian Aborigines and women were both excluded from the Australian constitution-making process–whereas both of these groups are full participants in any 21st century Australian constitution-amending process.[11] Stone argues that, in cases where the constitution-amending process is more democratic and inclusive–and thus more legitimate–than the constitution-making process is, it would indeed be permissible to enact even transformational constitutional changes through the constitution-amending process (as opposed to through a new constitution-making process).[11]

National views about this theory

Countries that adopted this theory

Germany

Contemporary Germany arose from the ashes of World War II and the totalitarian experience of Nazism. Based on the legacy of the Weimar Constitution and especially on the correction of its flaws, the Federal Republic of Germany was born in 1949 (as West Germany) and the Federal Constitutional Court has been active since 1951. The court's jurisdiction is focused on constitutional issues and the compliance of all governmental institutions with the constitution. Both ordinary laws and constitutional laws (and amendments) passed by the Parliament are subject to its judicial review, since they have to be compatible with the principles of the Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany defined by the eternity clause.[12]

Honduras

In 2015, the Supreme Court of Honduras declared unconstitutional a part of the original 1982 constitution of Honduras that created a one-term limit for the president of Honduras and also created protective provisions punishing attempts to alter this presidential term limit.[13] This case was novel in the sense that a part of an original constitution rather than a constitutional amendment was declared unconstitutional.[13]

India

In the 1960s and 1970s, the Indian Supreme Court articulated the basic structure doctrine—as in, the idea that a constitutional amendment that violates the basic structure of the Indian Constitution should be declared unconstitutional.[14] This was a significant reversal from 1951—when the Indian Supreme Court declared that the constitutional amendment power was unlimited.[15]

Israel

Israel does not have a unified constitution; its legal framework is instead codified in a series of quasi-constitutional Basic Laws.

In July 2023, the ruling coalition under Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu passed an amendment to Basic Law: The Judiciary, which defines the powers of that branch of government. It would have limited the powers of the Supreme Court of Israel to strike down legislation that it considers contrary to the Basic Laws. The law was very controversial and led to widespread protests in the country.[16]

On 1 January 2024, the Supreme Court ruled 12-3 that it may reject amendments to Basic Laws in "extreme" circumstances. That specific amendment was struck down by an 8-7 vote.[16] In the decision, the justices noted that the judicial overhaul would jeopardise the basic characteristic of Israel as a democratic country.[17]

Italy

Similar to Germany, the Italian Republic was born out of fascism. The Constitution of Italy, effective since 1948, is largely amendable, however the Constitutional Court of Italy (active since 1955) decides on the constitutionality of both ordinary laws and constitutional laws, for example, in respects to inviolable human rights, highlighted by the Constitution's "Article 2".[18] The Constitutional Court's ruling is final and not subject to appeal.

An example of an unconstitutional constitutional amendment would be a measure to restore the monarchy, which was abolished in 1946. This is because Italy's republican form of government is explicitly protected in an entrenched clause, which is impossible to amend.

Taiwan (Republic of China)

Even though the ROC Constitution made no mentioning of judicial reviews of constitutional amendments, in Interpretation No. 499, the Council of the Grand Justices (Constitutional Court) declared a Constitutional Amendment unconstitutional and struke it down. This set the precedence of court review of constitutional amendments in Taiwan ROC.

Countries that rejected this theory

Finland

The Parliament of Finland enjoys parliamentary sovereignty: its acts do not undergo judicial review, and cannot be stricken down by any court, so the constitutionality of a constitutional amendment is a purely political question. A 5⁄6 supermajority can immediately enact an emergency constitutional amendment. In 1973, President of Finland Urho Kekkonen requested a four-year term extension by means of an emergency constitutional amendment, in order to avoid arranging presidential elections. He succeeded in persuading the opposition National Coalition Party and Swedish People's Party to vote for the amendment, and got his extension.

Finland has had for most of its independence a semi-presidential system, but in the last few decades the powers of the President have been diminished. Constitutional amendments, which came into effect in 1991 and 1992, as well as the most recently drafted constitution of 2000 (amended in 2012), have made the presidency a primarily ceremonial office.

United Kingdom

The Constitution of the United Kingdom is not strictly codified in contrast to that of many other nations. This enables the constitution to be easily changed as no provisions are formally entrenched.[19] The United Kingdom has a doctrine of parliamentary sovereignty,[20] so the Supreme Court of the United Kingdom (active since 2009) is in fact limited in its powers of judicial review as it cannot overturn any primary legislation made by the Parliament of the United Kingdom and any Act of Parliament can become part of the UK's constitutional sources without binding scrutiny.

Potential future applications

In a 2016 op-ed, published just a month after the 2016 US presidential election, US law professor Erwin Chemerinsky argued that the United States Supreme Court should declare the unequal allocation of electoral college votes to be unconstitutional due to it being (in his opinion) contrary to the equal protection principles that the US Supreme Court has found in the Fifth Amendment.[21] Chemerinsky argues that a part of the United States Constitution can be unconstitutional if it conflicts with some principle(s) in a subsequent US constitutional amendment (specifically as this amendment is interpreted by the courts).[21] At around the same time that Chemerinsky published his op-ed, in an article in the Huffington Post, US law professor Leon Friedman made an argument similar to Chemerinsky's.[22]

In a 2018 blog post, US law professor Michael Dorf points out that it is possible (as opposed to plausible) for the United States Supreme Court (SCOTUS) to utilize the unconstitutional constitutional amendment doctrine to strike down the unequal apportionment in the United States Senate (which violates the one person, one vote principle); in the very same article, however, Dorf also expresses extreme skepticism that the US Supreme Court (or even a single justice on the US Supreme Court) would actually embrace the unconstitutional constitutional amendment doctrine—at least anytime soon.[3]

In a 2019 article, Yaniv Roznai and Tamar Hostovsky Brandes embraced the argument previously proposed by Rosalind Dixon and David Landau and argued that since the constitutional replacement process can also be abused, it would be permissible and legitimate for courts to strike down constitutional replacements that are not fully democratic or inclusive.[23] In other words, Yoznai and Hostovsky Brandes argue that the more the constitutional replacement process resembles the secondary constituent power (as opposed to the primary constituent power), the more legitimate it would be for the judiciary to strike down any constitution that was produced through a constitutional replacement process.[23]

Criticism

United States law professor Mike Rappaport criticizes the unconstitutional constitutional amendment doctrine and argues that the adoption of this doctrine in the US would undermine popular sovereignty because nine unelected US Supreme Court Justices with life tenure would give themselves the power to overturn the will of a huge majority of the American people.[2] Rappaport points out that having the US Supreme Court adopt this doctrine might not always result in outcomes that liberal living constitutionalists are actually going to like (for instance, Rappaport argues that the US Supreme Court could use this doctrine to strike down a new constitutional amendment that will overturn the 2010 Citizens United ruling due to a belief that this new amendment conflicts with the First Amendment and the idea of free speech that the First Amendment embodies) and also argues that such a move on the part of the US Supreme Court would obstruct the US constitutional amendment process even further because people might hesitate to put effort into passing a new constitutional amendment if they thought that the US Supreme Court could strike down the amendment and declare it unconstitutional.[2] Rappaport is also critical of the tendency in the US to use the judiciary to achieve various constitutional changes outside of the Article V constitutional amendment process because this reduces the incentive to actually pass and ratify new US constitutional amendments since achieving constitutional change through the courts is astronomically easier than going through the extremely long and cumbersome Article V constitutional amendment process (as convincing five or more Justices on the US Supreme Court to agree with one's position is astronomically easier than getting two-thirds of the US Congress and three-fourths of US state legislatures to agree with one's position).[2]

Meanwhile, Conall Towe criticizes the unconstitutional constitutional amendment doctrine for violating two canons of construction: specifically the lex specialis canon and the expressio unius est exclusio alterius canon.[24] The lex specialis canon states that specific language should trump general language whenever possible–with Towe citing a statement by Professor Oran Doyle that "it is not permissible to over-write one clear provision in favour of an amorphous spirit that has no particular textual foundation".[24] Specifically, Towe uses an argument that George Washington Williams previously used back in 1928–as in, "if the constituent power is all-powerful, and the constituent power is expressed via the text of the constitution[,] then it is difficult to see how implicit unamendability on the basis of constituent power theory can avoid [the] charge [that] it simultaneously disregards the constitution under the pretence of upholding it."[24] Meanwhile, the expressio unius est exclusio alterius canon states that the specific inclusion of one thing in a legal text or document excludes other things that were not mentioned in it.[24] While Towe argues that a literal reading of the constitutional text can be ignored in cases where it will produce an absurd outcome–a move that is in fact permitted by the absurdity doctrine–Towe rejects the idea that carefully crafted unlimited amendment powers are absurd.[24] Towe also wonders why exactly any constitutional provisions were made explicitly unamendable if implicit unamendability is so obvious; after all, if implicit unamendability was indeed so obvious, then there would be no need to make any constitutional provisions explicitly unamendable.[24] In contrast, if certain provisions were made explicitly unamendable, Towe wonders why exactly the draftsmen of a particular constitution would not have made explicitly unamendable all of the constitutional provisions that they indeed wanted to be unamendable.[24]

On a separate note, Conall Towe also criticizes Yaniv Roznai's conceptual framework in regards to primary constituent power and secondary constituent power for violating Occam's Razor, which states that the simplest explanations possible for various phenomena should be preferred.[24] Professor Oran Doyle has also previously criticized Yaniv Roznai's conception of the people as primary constituent power and the people as secondary constituent power as separate entities for violating Occam's Razor–with Doyle arguing that constituent power should be best thought of as a capacity rather than as an entity.[25]

In a 1985 article of his, United States law professor John R. Vile argues against the idea of having judges impose implicit limits on the United States constitutional amendment power for fear that such judicial power could just as easily be used for bad or evil ends as for good or desirable ends–especially if the original text of a particular constitution, such as the original text of the United States Constitution, is not particularly liberal or progressive to begin with.[26] For instance, Vile points out that a reactionary United States Supreme Court could have struck down the progressive Reconstruction Amendments (which abolished slavery and extended both human rights and the suffrage to African-Americans) as being unconstitutional and also struck down hypothetical progressive amendments that would extend legal protection to the handicapped, the aged, and the unborn.[26] Vile also argues that the United States constitutional amendment process is meant to serve as a "safety-valve" in order to provide a legal avenue to achieving constitutional change–however radical and far-reaching–so that revolution in the United States can be avoided.[26] Vile argues that without any legal avenue to achieve certain constitutional changes, the American people might feel compelled to spark a revolution in order to achieve their desired changes to the United States constitutional order.[26]

Responses to criticism

In response to criticism that the unconstitutional constitutional amendment theory blocks constitutional change, US law professor David Landau pointed out that this theory has ways to get around it.[27] Specifically, Landau argues that political actors can engage in wholesale constitutional replacement in response to a judicial ruling that declares a particular constitutional amendment to be unconstitutional and also argues that political actors can "exert influence over the court[s] through appointments and other devices[]" in order to have the courts deliver rulings in these political actors' favor.[27] Thus Landau, along with Australian law professor Rosalind Dixon, argues that a "speed bump" is the more proper comparison for the unconstitutional constitutional amendment doctrine and that while the unconstitutional constitutional amendment doctrine can delay change–perhaps with the hope of allowing a new political configuration to emerge in the meantime–it cannot permanently prevent constitutional change because political actors have workarounds (specifically those mentioned earlier in this paragraph) to achieve constitutional change even in the face of an initially hostile judiciary.[27]

See also

References

- 1 2 Roznai, Yaniv (September 19, 2017). Unconstitutional Constitutional Amendments: The Limits of Amendment Powers. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198768791 – via Google Books.

- 1 2 3 4 Rappaport, Mike (June 28, 2018). "The Problems With Declaring Procedurally Valid Constitutional Amendments to be Unconstitutional". The Originalism Blog. Retrieved September 21, 2019.

- 1 2 Dorf, Michael C. (November 12, 2018). "How Much of a Problem is the Senate?". Take Care. Retrieved September 21, 2019.

- ↑ Roznai, Yaniv (September 13, 1971). "Towards A Theory of Constitutional Unamendability: On the Nature and Scope of the Constitutional Amendment Powers". Juspoliticum.com. Retrieved October 11, 2019.

- ↑ Machen, Arthur W. (1910). "Is the Fifteenth Amendment Void?". Harvard Law Review. 23 (3): 169–193. doi:10.2307/1324228. JSTOR 1324228.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Could a Constitutional Amendment be Unconstitutional?" (PDF). IUPUI ScholarWorks. Loyola University Chicago Law Journal. 1991. Retrieved July 9, 2021.

- 1 2 Roznai, Yaniv (February 2014). "Unconstitutional Constitutional Amendments: A Study of the Nature and Limits of Constitutional Amendment Powers" (PDF). The London School of Economics and Political Science. pp. 1–373 – via etheses.lse.ac.uk.

- ↑ Roznai, Yaniv (August 24, 2015). "The Spectrum of Constitutional Amendment Powers". SSRN 2649816 – via papers.ssrn.com.

- ↑ Bernal-Pulido, Carlos; Roznai, Yaniv (October 17, 2013). "Article Review/Response, Unconstitutional Constitutional Amendments in the Case Study of Colombia". International Journal of Constitutional Law Blog – via www.iconnectblog.com.

- 1 2 3 Colon-Rios, Joel I (2018). "Enforcing the Decisions of the People Book Reviews". Constituntional Commentary. University of Minnesota Law School. 33: 1–7 – via scholarship.law.umn.edu.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Stone, A --- "Unconstitutional Constitutional Amendments: Between Contradiction and Necessity" [2018] UMelbLRS 9". classic.austlii.edu.au.

- ↑ Article 79 paragraph (3) of the Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany.

- 1 2 Roznai, Yaniv; Dixon, Rosalind; Landau, David (July 4, 2018). "From an Unconstitutional Constitutional Amendment to an Unconstitutional Constitution? Lessons From Honduras by David Landau, Rosalind Dixon, Yaniv Roznai :: SSRN". FSU College of Law, Public Law. SSRN 3208185.

- ↑ Stith, Richard (1996). "Unconstitutional Constitutional Amendments: The Extraordinary Power of Nepal's Supreme Court". American University International Law Review. American University. 11 (1): 47–77 – via american.edu.

- ↑ Albert, Richard (2018). "Constitutional Amendment and Dismemberment". The Yale Journal of International Law. 43 (1): 1–84 – via digitalcommons.law.yale.edu.

- 1 2 Sharon, Jeremy (January 1, 2024). "In historic 1st, High Court strikes down Basic Law amendment, voiding reasonableness law". The Times of Israel.

- ↑ Rabinovitch, Ari (January 1, 2024). "Israel's Supreme Court strikes down disputed law that limited court oversight". Reuters.

- ↑ Bin, Roverto and Pitruzella, Giovanni (2008), Diritto costituzionale, G. Giappichelli Editore, Turin, p. 326.

- ↑ King, Anthony (2007). The British Constitution. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- ↑ "Parliamentary Sovereignty". GOV.UK. Retrieved January 22, 2020.

- 1 2 Chemerinsky, Erwin (December 13, 2016). "Why the Electoral College system violates the Constitution: Erwin Chemerinsky – Daily News". Dailynews.com. Retrieved October 8, 2019.

- ↑ Friedman, Leon (November 18, 2016). "Is The Electoral College System For Choosing Our President Unconstitutional?". HuffPost. Retrieved October 8, 2019.

- 1 2 Roznai, Yaniv; Brandes, Tamar Hostovsky (May 26, 2019). "Democratic Erosion, Populist Constitutionalism and the Unconstitutional Constitutional Amendment Doctrine". doi:10.2139/ssrn.3394412. S2CID 197775549. SSRN 3394412 – via papers.ssrn.com.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "Constituent Power and Doctrines of Unconstitutional Constitutional Amendments". January 21, 2020.

- ↑ Doyle, Oran (April 21, 2019). "Populist constitutionalism and constituent power". German Law Journal. 20 (2): 161–180. doi:10.1017/glj.2019.11.

- 1 2 3 4 Vile, John R. (1985). "Limitations on the Constitutional Amending Process". Constitutional Commentary. University of Minnesota Law School. 2: 373–388 – via scholarship.law.umn.edu.

- 1 2 3 "Yale Journal of International Law | Archives | 2018 | February". Yjil.yale.edu. Retrieved April 2, 2020.