| United States v. Nice | |

|---|---|

| |

| Argued April 24, 1916 Decided June 12, 1916 | |

| Full case name | United States, Plff. in Err., v. Fred Nice. |

| Citations | 241 U.S. 591 (more) 36 S. Ct. 696; 60 L. Ed. 1192 |

| Holding | |

| United States citizenship is not incompatible with tribal existence or continued guardian ship; therefore, Native Americans who are granted citizenship are still subject to protection by congress’s plenary power.[1] | |

| Court membership | |

| |

| Case opinions | |

| Majority | Van Devanter, joined by White, McKenna, Holmes, Pitney, McReynolds |

| Concur/dissent | Day, Hughes |

| Laws applied | |

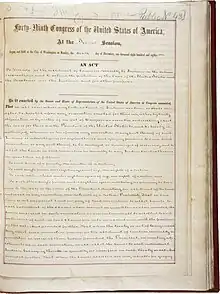

| Dawes Act | |

United States v. Nice, 241 U.S. 591 (1916), is a United States Supreme Court decision which declared that Congress still retains plenary power to protect Native American interests when Native Americans are granted citizenship. United States v. Nice overruled the Heff decision which declared that Native Americans granted citizenship by the Dawes Act were also then citizens of the state in which they resided, meaning the sale of alcohol to such Native Americans was not subject to Congress's authority.[2]

Facts

In 1897, an amendment to the Indian Appropriations Act banned the sale of alcohol to Indians. Citizenship of the parties involved was never clarified. In the Supreme Court case Matter of Heff, the decision clarified that a Native American granted citizenship through the Dawes Act is immediately a citizen of the U.S. and his state. The 1897 amendment banning alcohol was considered a police statute, where power lies with the state and not Congress, and therefore would not apply to such a citizen. Representative of South Dakota, Charles H. Burke, saw the need to correct the situation in order to protect Native Americans from the sale of liquor. He amended the Dawes Act so that citizenship was only granted to a Native with an allotment after the trust period ran out (usually 25 years [3]). This amendment was meant to allow Congress to continue to safeguard Indians’ personal welfare. However, those who received allotments before the amendment was signed into law on May 8, 1906, were still considered state citizens and not subject to federal authority except when concerning their land. The amendment only put the alcohol ban into effect for Natives receiving allotments after May 8, 1906. When Fred Nice was indicted for selling alcohol to a Native American who received an allotment before 1906, he was acquitted in a lower court using the Heff decision as his defense,[2] but the U.S. appealed, represented by Assistant Attorney General Warren. Warren argued that the Pelican Case, 232 U.S. 214 (1914) proved federal authority and overruled the Heff decision.[4]

Holding

The court held that congress would retain plenary power to protect Native Americans. Such plenary power is based on "the clause in the Constitution expressly investing Congress with authority 'to regulate commerce . . . with the Indian tribes,'" and the perceived dependence of tribes on the United States.[4] This decision meant the federal government could regulate Indian alcohol policy through the commerce clause and state powers could regulate Indian alcohol policy through the power of the police to regulate the conduct of citizens.[5] The major ruling is summed up by the following quote:

“Citizenship is not incompatible with tribal existence or continued guardianship, and so may be conferred without completely emancipating the Indians, or placing them beyond the reach of congressional regulations adopted for their protection.”[4]

The decision was based on a complete review of the Dawes Act which found that congress must have wanted to continue the ward- guardian relationship because it retained control over Indian money to look over “education and civilization.” [2] The ruling in United States v. Nice overruled the Heff decision, claiming it was "Not well grounded."[4] The decision also references United States v. Holliday 70 U.S. 407 (1865) to show Congress's ability to regulate commerce. Another reference is made to United States v. Kagama to show the dependence of tribes on the United States. A similar situation in the case United States v. Sandoval is referenced to show that citizenship of the Indian party is not relevant to the issue of Congress's authority.

Implications

The legal position of Native Americans during the time of the case could be compared to that of a Minor. Minors are citizens with guardians and have special laws applying only to them. Native Americans were set to have Congress as a guardian.[2] This status stemmed from the view of Native Americans as an inferior race, as exemplified by the United States Supreme Court case Johnson v. McIntosh.[6] Native Americans were viewed as unable to resist or handle alcohol.[5] Congress viewed United States citizenship as a method of civilizing Native Americans.[7] The treatment of citizenship in United States v. Nice implies the inferiority of Indians and allows for individual liberties of Native Americans to be restricted based on such an implication.[8]

Effects

United States v. Nice was referenced in the case United States v. Mazurie to support the court's decision to uphold a conviction of selling alcohol in Indian Country against non-Indians on the Wind River Reservation who had been denied a tribal liquor license.[9] United States v. Nice upheld Congressional power to regulate any commercial transaction involving individual Indians or a tribe,[10] wherever situated, and to regulate the introduction of alcoholic beverages into Indian country.[9]

In his book American Indian Sovereignty and the U.S. Supreme Court: The Masking of Justice, David E. Wilkins claims that the decision in United States v. Nice "Muffled rights of individual Indians as federal citizens." The court's decision continued the contradictory treatment of Native Americans with the incongruous ideas of Indians as dependent people in need of protection and Indians as United States Citizens.[11]

United States v. Nice upheld the plenary power of Congress. The nearly unlimited power of Congress to adjust Indian rights still exists today. However, in the late 1960s and 1970s, congressional leadership began to see Indian policy in a new light. The past half century has seen a surge of laws favorable to Indians which allow tribes much more influence over their own futures.[12] In fact, some Native Tribes, including the Yakama Nation, have banned alcohol on their reservations through acts of tribal sovereignty.[13]

Notes

- ↑ Duthu, Bruce. American Indians and the Law. New York: Penguin Books, 2008. (138) Print.

- 1 2 3 4 Smith, Michael. “The History of Indian Citizenship.” Great Plains Journal. 10.1 (Fall 1970): 33–35. Print.

- ↑ Canby Jr., William. American Indian Law In a Nut Shell, 4th edition. West Group, 2004. (21) Print.

- 1 2 3 4 United States v. Nice, 241 U.S. 591 (1916).

- 1 2 Miller, Robert J. "The 'Drunken Indian': Myth Distilled into Reality Through Federal Indian Alcohol Policy." Arizona State Law Journal. 28.223 (Spring 1996)

- ↑ Duthu, Bruce. American Indians and the Law. New York: Penguin Books, 2008. (73) Print.

- ↑ Wilkins, David E. American Indian Sovereignty and the U.S. Supreme Court: The Masking of Justice. University of Texas Press, 1997. (119) Print.

- ↑ Wilkins, David E. American Indian Sovereignty and the U.S. Supreme Court: The Masking of Justice. University of Texas Press, 1997. (136) Print.

- 1 2 United States v. Mazurie, 419 U.S. 544 (1975).

- ↑ Ott, Brian R. "Indian Fishing Rights in the Pacific Northwest: The Need for Federal Intervention." Boston College Environmental Affairs Law Review. 14.313 (Winter 1987)

- ↑ Wilkins, David E. American Indian Sovereignty and the U.S. Supreme Court: The Masking of Justice. University of Texas Press, 1997. (118) Print.

- ↑ Wilkinson, Charles. Blood Struggle: The Rise of Modern Indian Nations. New York: Norton & Company, 2005. (242) Print.

- ↑ Haupt, Robert J. "Never Lay a Salmon on the Ground with his Heas Toward the River": State of Washington Sues Yakamas over Alcohol Ban. American Indian Law Review. 26.67 (2001)

External links

- Text of United States v. Nice, 241 U.S. 591 (1916) is available from: CourtListener Findlaw Justia Library of Congress