| United States v. Singer Mfg. Co. | |

|---|---|

| |

| Argued April 25, 29, 1963 Decided June 17, 1963 | |

| Full case name | United States v. Singer Manufacturing Company |

| Citations | 374 U.S. 174 (more) |

| Case history | |

| Prior | 205 F. Supp. 394 (S.D.N.Y. 1962) |

| Subsequent | 231 F. Supp. 240 (S.D.N.Y. 1964) |

| Court membership | |

| |

| Case opinions | |

| Majority | Clark, joined by Warren, Black, Douglas, Brennan, Stewart, White, Goldberg |

| Concurrence | White |

| Dissent | Harlan |

United States v. Singer Mfg. Co., 374 U.S. 174 (1963), was a 1963 decision of the Supreme Court, holding that the defendant Singer violated the antitrust laws by conspiring with two European competitors to exclude Japanese sewing machine competition from the US market.[1] Singer effectuated the conspiracy by agreeing with the two European competitors to broaden US patent rights and concentrate them under Sanger's control in order to more effectively exclude the Japanese firms. A further aspect of the conspiracy was to fraudulently procure a US patent and use it as an exclusionary tool. This was the first Supreme Court decision holding that exclusionary use of a fraudulently procured patent could be an element supporting an antitrust claim.[1]

Background

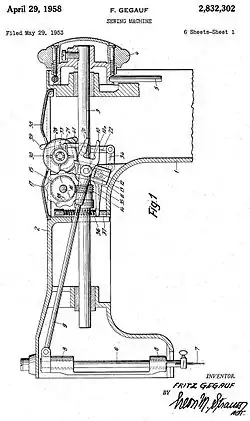

The United States brought a civil action against Singer Manufacturing Co. (now Singer Corporation), the sole American manufacturer of household zigzag sewing machines,[2] to restrain Singer from conspiring with two of its competitors that also manufactured such machines, Vigorelli, an Italian manufacturer, and Gegauf, a Swiss manufacturer. The conspiracy alleged was one to restrain the importation into the United States of such machines. The targets of the conspiracy were Japanese manufacturers, that were under-pricing the conspirators in the US market.[3]

Singer accounted for 61% of US sales in 1959, Japanese manufacturers sold 23%, and European manufacturers sold the remaining 16%. Shortly before the events of this case, Singer filed patent applications on zig zag sewing machines. Vigorelli also filed patent applications, and it appeared to Singer that its design would infringe Vigorelli's patents if they issued. Singer concluded that litigation would result between it and Vigorelli unless a cross-licensing agreement could be made, and this was effectuated in November 1955. In the agreement, each party agreed not to make any legal challenge against the other's patents.[4]

Singer then learned that Gegauf had a pending US application that predated Singer's and would likely overcome Singer's. Singer then arranged a meeting with Gegauf. Singer used Gagauf's concern with the inroads that the Japanese manufacturers were making on the US market as a "lever" to persuade Gegauf that it would be in their mutual interest to join forces to exclude the Japanese instead of litigating against one another. Singer's "strong point" in the discussions "was that an agreement should be made 'in order to fight against this Japanese competition in their building a machine that in any way reads on the patents of ourselves and [Gegauf] which are in conflict.'" Singer and Gegauf then entered into a cross-license in which they agreed not to interfere with one another's efforts to gain broad patent coverage.[5]

Singer then persuaded Gegauf that Singer could better prosecute the Gegauf patent in the United States and enforce it against the Japanese than Gegauf could, including doing so by combining the Singer and Gegauf patents in Singer's hands. Finally, Gegauf assigned to Singer its pending patent application and all rights in the invention claimed and to all United States patents which might be granted under it, for a price that the Court considered lower than its fair market value.[6]

Gegauf's patent issued and was assigned to Singer in 1958, and Singer promptly sued importers and distributors of Japanese zig zag machines for infringement of the patent. Singer also brought a proceeding before the US Tariff Commission under 19 U.S.C. § 1337[7] against the importation of Japanese machines, which remained pending during the government antitrust case.[8]

The district court, after a bench trial, held on the basis of the foregoing facts that no antitrust violation occurred.[9] The government then appealed to the Supreme Court.

Supreme Court ruling

The government claimed in the Supreme Court that Singer engaged in a series of transactions with Gegauf and Vigorelli for an illegal purpose, i.e., to rid itself and Gegauf, together, perhaps, with Vigorelli as well, of infringements by their common competitors, the Japanese manufacturers. The government claimed that the parties entered into an agreement that had an identity of purpose and they took actions in pursuance of it that, in law, amount to a combination or conspiracy in violation of § 1 of the Sherman Act, 15 U.S.C. § 1. "There is no claim by the Government that it is illegal for one merely to acquire a patent in order to exclude his competitors; or that the owner of a lawfully acquired patent cannot use the patent laws to exclude all infringers of the patent; or that a licensee cannot lawfully acquire the covering patent in order better to enforce it on his own account, even when the patent dominates an industry in which the licensee is the dominant firm." The Court said that it would "put all these matters aside without discussion.[10]

Majority opinion

.jpg.webp)

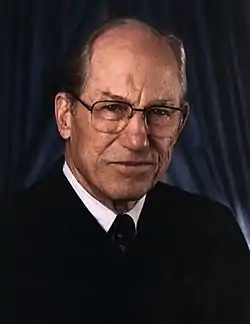

Justice Tom Clark wrote the majority opinion. He explained that by combining the patent interests of the companies in Singer's hands "to stifle competition" from the Japanese manufacturers, the conspirators more effectively were able to exclude competition against themselves. In particular, the Tariff Commission proceeding based on infringement of the Gegauf patent could be brought only on behalf of a US complaining company. Gegauf and Vigorelli could not bring such complaints to the Tariff Commission under 19 U.S.C. § 1337.[11]

On the basis of Singer's overall pattern of conduct, the Court reversed the judgment of the district court and remanded the case for entry of a decree against Singer.[12]

Concurring opinion

Justice Byron White filed an opinion concurring in the judgment, but he would have separated the case into two branches, each of which was a violation of § 1 of the Sherman Act:

There are two phases to the Government's case here: one, the conspiracy to exclude the Japanese from the market, and the other, the collusive termination of a Patent Office interference proceeding pursuant to an agreement between Singer and Gegauf to help one another to secure as broad a patent monopoly as possible, invalidity considerations notwithstanding. The Court finds a violation of § 1 of the Sherman Act in the totality of Singer's conduct, and intimates no views as to either phase of the Government's case standing alone. ... [I]n my view, either branch of the case is sufficient to warrant relief. ...[13]

Justice White then turned his attention to the Patent Office proceeding. Singer withdrew from an interference with Gegauf, so that Gegauf would have no difficulty in obtaining the US patent (which then went to Singer under the agreement). Gegauf had been afraid that

Singer might, in self-defense, draw to the attention of the Patent Office certain earlier patents the Office was unaware of, and which might cause the Gegauf claims to be limited or invalidated; Singer "let them know that we thought we could knock out their claims, but that, in so doing, we were probably going to hurt both of us."[14]

Justice White explained that the Singer-Gegauf agreement to keep prior art from the notice of the Patent Office was itself a criminal action:

In itself, the desire to secure broad claims in a patent may well be unexceptionable—when purely unilateral action is involved. And the settlement of an interference in which the only interests at stake are those of the adversaries, as in the case of a dispute over relative priority only and where possible invalidity, because of known prior art, is not involved, may well be consistent with the general policy favoring settlement of litigation. But the present case involves a less innocuous setting. Singer and Gegauf agreed to settle an interference at least in part to prevent an open fight over validity. There is a public interest here, which the parties have subordinated to their private ends—the public interest in granting patent monopolies only when the progress of the useful arts and of science will be furthered because as the consideration for its grant the public is given a novel and useful invention. When there is no novelty and the public parts with the monopoly grant for no return, the public has been imposed upon, and the patent clause subverted. Whatever may be the duty of a single party to draw the prior art to the Office's attention, clearly collusion among applicants to prevent prior art from coming to or being drawn to the Office's attention is an inequitable imposition on the Office and on the public. In my view, such collusion to secure a monopoly grant runs afoul of the Sherman Act's prohibitions against conspiracies in restraint of trade—if not bad per se, then such agreements are at least presumptively bad. The patent laws do not authorize, and the Sherman Act does not permit, such agreements between business rivals to encroach upon the public domain and usurp it to themselves.[15]

Dissenting opinion

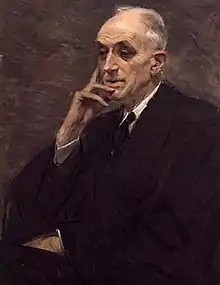

Justice John Marshall Harlan II filed a dissenting opinion. In his view the case turned on what he considered the "invulnerable" findings of the district court that no agreement to restrain trade occurred.[16]

District court remand decision

On remand from the Supreme Court, the district court entered a decree regarding patent issues. The Government proposed a judgment that would enjoin the defendant Singer from enforcing all five of its patents that the Government argued were the subject of the conspiracy. Singer argued that the court should limit the decree to one patent alone (the "Gegauf I" patent), which Singer argued was the only patent involved in the conspiracy and to compulsory licensing of that patent at a reasonable royalty rather than, in effect, royalty-free licensing.[17] Some of the patents were lawfully acquired but all five concerned zig-zag sewing machines, which were the subject of the conspiracy. The Government argued that Singer had misused all five patents and "should not be permitted to effectuate any part of the conspiracy by virtue of any of the five patents which it has." Further:

[W]hether or not the patents were lawfully acquired is immaterial, since they were employed to achieve an unlawful end. Answering Singer's position, the Government urges that the acquisition of "Gegauf I" was but one of the overt acts of the overall conspiracy which embraced all five patents, and that to grant relief only against the one patent is to leave the defendant free to employ the other four patents to accomplish the unlawful exclusion.[18]

The district court said, "The Government's theory is predicated on conspiracy directed to a particular type machine and defendant's theory is that it was a conspiracy directed to one patent." In the court's view, the theory of the Government's case, which the Supreme Court accepted, was that "Singer unlawfully acquired Gegauf I and II pursuant to the conspiracy, with the purpose of using them in conjunction with" the other patents in order "to exclude Japanese competitors in household zigzag sewing machines." The district court therefore found that all five patents were relevant to the relief.[19]

The district court then turned to the reasonable royalty–royalty-free controversy. The Government argued that reasonable royalty licensing "does nothing but reward the defendant and permit it to continue the exclusion." The court disagreed, relying on Hartford-Empire Co. v. United States:[20]

Whatever the logic there may be in this argument (and it must be admitted that it is not entirely devoid of some rational basis), the Supreme Court has to date refused to approve either royalty-free licensing or non-enforcement of patents. . . . Mr. Justice Roberts in [Hartford-Empire] questioned the power of the Court in framing an anti-trust decree to order forfeiture of a patent, and reversed the district court which had so decreed. The principle underlying the decision was that since validity of the patents was not attacked their enforcement should not be restrained because it was an interference with the property right of the patent. The dissent supported the Government's position that the patents were not only the weapons of the conspiracy but its fruits, and that to restore competition it was necessary to decree royalty-free licensing. . . . In any event, the majority opinion of the Court equated compulsory royalty-free licensing with forfeiture of the patents, and in the face of the magnitude of the violation which in addition to a restraint of trade also included a monopoly, refused to affirm the decree of the lower court.[21]

The district court said that the test "which must guide the Court in framing an anti-trust decree is what measure must be applied in order to dispel the evil effect of the defendant's wrongful conduct, which means what will restore competition." It therefore ordered a reasonable royalty decree for the five patents.[22]

Subsequent developments

In Walker Process Equipment, Inc. v. Food Machinery & Chemical Corp.,[23] the Supreme Court extended the ruling in this case by holding that a private party injured by enforcement of a fraudulently procured patent could bring a private antitrust suit, if the enforcement had a substantial anticompetitive effect. The reasoning of the Court in Walker Process is similar to that of the concurring opinion of Justice White in the Singer case.

The court considered the FTC's cease-and desist order against several US manufacturers of tetracycline in American Cyanamid Co. v. FTC.[24] In that case Pfizer and Cyanamid cross-licensed one another; Cyanamid made erroneous representations to the Patent Office concerning matters bearing upon the patentability of tetracycline; and although Cyanamid soon discovered that these representations were inaccurate, it did not disclose this fact to the Patent Office until after the tetracycline patent had been granted to Pfizer, thereby aiding Pfizer in its efforts to obtain a patent monopoly. The FTC ruled that this suppression of material information, combined with the cross-licensing agreement between Pfizer and Cyanamid and the acceptance by the latter of a license from the former to produce and sell tetracycline, constituted an illegal attempt to share a monopoly with Pfizer and amounted to a combination in restraint of trade. Although the court vacated and ordered retrial on a technical issue (disqualification of a commissioner) and evidentiary shortcomings, it upheld the FTC's jurisdiction in the matter. In so ruling, the court cited the concurring opinion of Justice White in Singer to underscore the seriousness of the misconduct in procuring the tetracycline patent and how it could properly be the basis for an FTC proceeding against an unfair method of competition under § 5 of the FTC Act.[25]

In FTC v. Activis, Inc.,[26] the Supreme Court discussed the Singer case and said it exemplified the principle that patent settlement agreements should be evaluated by measuring the settlement's anticompetitive effects against procompetitive antitrust policies rather than solely against patent law policy. The Activis Court pointed out that in Singer:

The Court did not examine whether, on the assumption that all three patents were valid, patent law would have allowed the patents' holders to do the same. Rather, emphasizing that the Sherman Act "imposes strict limitations on the concerted activities in which patent owners may lawfully engage," it held that the agreements, although settling patent disputes, violated the antitrust laws.[27]

Then, citing the concurring opinion, the Court said that in Activis as in Singer it was important that the settlement not run counter to public policy by shielding an invalid patent from legal scrutiny.[28]

References

The citations in this article are written in Bluebook style. Please see the talk page for more information.

- 1 2 United States v. Singer Mfg. Co., 374 U.S. 174 (1963).

- ↑ "The zigzag stitch [sewing] machine produces various ornamental and functional zigzag stitches, as well as straight ones. The automatic multi-cam zigzag machine, unlike the manually operated zigzag and the replaceable cam machine, each of which requires hand manipulation or insertion, operates in response to the turning of a knob or dial on the exterior of the machine. While the multi-cam machines involved here function in slightly different ways, all are a variant of the same basic principle." 374 U.S. at 176. See also Sewing machine#Zigzag stitch.

- ↑ 374 U.S. at 175.

- ↑ 374 U.S. at 176-79.

- ↑ 374 U.S. at 180.

- ↑ 374 U.S. at 184-87.

- ↑ At that time, only a domestic manufacturer could instigate such a proceeding. Gegauf and Vigorelli could not do so. 374 U.S. at 195.

- ↑ 374 U.S. at 188-89.

- ↑ United States v. Singer Mfg. Co., 205 F. Supp. 394 (S.D.N.Y. 1962).

- ↑ 374 U.S. at 189.

- ↑ 374 U.S. at 192-95.

- ↑ 374 U.S. at 197.

- ↑ 374 U.S. at 197 (White, J., concurring in the judgment).

- ↑ 374 U.S. at 198.

- ↑ 374 U.S. at 199-200 (citations omitted).

- ↑ 374 U.S. at 202 (Harlan, J., dissenting).

- ↑ United States v. Singer Mfg. Co., 231 F. Supp. 240, 241 (S.D.N.Y. 1964).

- ↑ 231 F. Supp. at 241

- ↑ 231 F. Supp. at 241-42.

- ↑ Hartford-Empire Co. v. United States, 323 U.S. 386 (1945).

- ↑ 241 F. Supp. at 243-44.

- ↑ 241 F. Supp. at 244.

- ↑ Walker Process Equipment, Inc. v. Food Machinery & Chemical Corp., 382 U.S. 172 (1965).

- ↑ American Cyanamid Co. v. FTC, 363 F.2d 757 (6th Cir. 1966).

- ↑ On remand, the FTC reached the same result and this time the court upheld and enforced the FTC's order. Charles Pfizer & Co., Inc. v. FTC, 401 F.2d 574, 577-78 (6th Cir. 1968).

- ↑ FTC v. Activis, Inc., 570 U.S. 756 (2013).

- ↑ 570 U.S. at _ (citations omitted).

- ↑ Id. See also Lear, Inc. v. Adkins, 395 U.S. 653 (1969).

External links

- Text of United States v. Singer Mfg. Co., 374 U.S. 174 (1963) is available from: CourtListener Google Scholar Justia Library of Congress Oyez (oral argument audio)