United States war plans for a conflict with the Soviet Union (USSR) were formulated and revised on a regular basis between 1945 and 1950. Although most were discarded as impractical, they nonetheless would have served as the basis for action had a conflict occurred. At no point was it considered likely that the Soviet Union or United States would resort to war, only that one could potentially occur as a result of a miscalculation. Planning was conducted by agencies of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, in collaboration with planners from the United Kingdom and Canada.

American intelligence assessments of the Soviet Union's capabilities were that it could mobilize as many as 245 divisions, of which 120 could be deployed in Western Europe, 85 in the Balkans and Middle East, and 40 in the Far East. All war plans assumed that the conflict would open with a massive Soviet offensive. The defense of Western Europe was regarded as impractical, and the Pincher, Broiler and Halfmoon plans called for a withdrawal to the Pyrenees, while a strategic air offensive was mounted from bases in the United Kingdom, Okinawa, and the Cairo-Suez or Karachi areas, with ground operations launched from the Middle East aimed at southern Russia. By 1949, priorities had shifted, and the Offtackle plan called for an attempt to hold Soviet forces on the Rhine, followed, if necessary, by a retreat to the Pyrenees, or mounting an Operation Overlord–style invasion of Soviet-occupied Western Europe from North Africa or the United Kingdom.

Despite doubts about its viability and effectiveness, a strategic air offensive was regarded as the only means of striking back in the short term. The air campaign plan, which steadily grew in size, called for the delivery of up to 292 atomic bombs and 246,900 short tons (224,000 t) of conventional bombs. It was estimated that 85 percent of the industrial targets would be completely destroyed. These included electric power, shipbuilding, petroleum production and refining, and other essential war fighting industries. About 6.7 million casualties were anticipated, of whom 2.7 million would be killed. There was conflict between the United States Air Force and the United States Navy over naval participation in the strategic bombing effort, and whether it was a worthwhile use of resources. The concept of nuclear deterrence did not figure in the plans.

Background

In 1944, at the height of World War II, the Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) forecast that the war would result in the United States and the Soviet Union becoming the leading world powers. While Britain was still an important power, its position was greatly diminished.[1][2] On 5 February, the JCS produced an assessment of Soviet post-war intentions. It was expected that the Soviet Union would demobilize most of its forces to facilitate the reconstruction of its economy, which had been devastated by the war, and was not expected to recover before 1952. Until then, the Soviet Union would seek to avoid conflict, but for its own security it would attempt to control border states. Even after demobilization, the capabilities of the Soviet Union would be formidable. American intelligence reports estimated that it would retain over 4,000,000 troops under arms, with 113 divisions. Another 84 divisions would be available from satellite nations.[3]

During World War II, the United States mobilized the largest armed forces in American history. The United States Army, which at the time included the United States Army Air Forces (USAAF), had a strength of 8.3 million, of which 3 million were deployed in the European Theater of Operations, and the United States Navy and United States Marine Corps had a combined strength of 3.8 million. By early 1945, plans called for 21 divisions (about 1,000,000 personnel) to be redeployed from Europe to the Pacific via the United States for the invasion of Japan. About 400,000 personnel were to remain in Europe on military occupation duties, and the Army would release 2 million personnel from active duty under a points system whereby soldiers were awarded points based for length of service, length of overseas service, children and decorations. Those with the highest scores had priority for separation from the Army. By the time of the surrender of Japan in August 1945, 581,000 Army personnel had been separated. Under overwhelming public and political pressure, the demobilization of United States armed forces after World War II proceeded much faster than originally planned.[4] By 30 June 1946, the strength of the Army had declined to 1,434,000, the Navy to 983,000 and the Marine Corps to 155,000; by 30 June 1947, the Army was down to 990,000, the Navy to 477,000 and the Marine Corps to 82,000,[5] and only one division remained in Europe.[6] Meanwhile, the economies of European nations were still recovering from the war, and their ability to maintain forces was constrained.[7]

The Joint Staff Planners (JSP) consulted with Vannevar Bush, the Chairman of the Joint Committee on New Weapons and Equipment, and Major General Leslie R. Groves, the director of the Manhattan Project, on the potential of new weapons then under development, in particular nuclear weapons and long-range missiles. Bush doubted that it was possible to build a missile like the German V-2 rocket of World War II, but with an extended range of 2,000 nautical miles (3,700 km). Even if the rocket was possible, it would still require allied overseas bases to reach the Soviet Union. Groves was more optimistic; while he agreed that long-range missiles were not technologically feasible in 1945, he thought that they might be in the next ten to twenty years. As for atomic bombs, he recommended that a stockpile be built up but warned that the destruction of a nation's industrial capacity would not affect the outcome of a war.[8]

The JCS fashioned a defense posture and war plans oriented toward a single contingency—an all-out global conflict. Mainly they relied on strategic bombardment with nuclear weapons as the country’s principal deterrent and first line of defense. This strategy was found as most practical, effective, and affordable form of defense, and laid foundation for a series of war plans developed over the next few years for dealing with a possible conflict with the Soviet Union.[9]

Pincher (1946)

On 2 March 1946, the Joint War Plans Committee (JWPC) circulated a discussion paper for an outline war plan codenamed Pincher.[10] The outline, which was revised in April and June, estimated that the Soviets could deploy 270 divisions in Europe, 42 in the Middle East, and 49 in the Far East sixty days after mobilization.[11] The most likely flashpoint for hostilities was the Middle East, where Soviet ambitions might come into conflict with those of Britain. The United States would be neutral in such a conflict, but might eventually be drawn into it, as had occurred in 1917 and 1941. The Soviet Union had the resources to quickly overrun Europe east of the Rhine. The Rhine was a major barrier, but it was anticipated that it could not be held for long, forcing US and British forces to retreat to the Pyrenees.[10] The planners believed that the Italian, Iberian, Danish and Scandinavian peninsulas could be held against superior numbers, but expected that the British and French forces would concentrate on defending their homelands, and would be unwilling to divert the resources required to hold Scandinavia, although they might assist in attempting to hold Spain and Italy.[12] The Soviet drive into Western Europe would likely be accompanied by one into the Middle East. If the Soviets also attacked in the Far East, US forces would fall back to Japan.[10]

The objective of the United States forces would be to hold the British Isles, North Africa, India, China and Japan, from whence strategic air operations could be launched, while the Navy blockaded the Soviet Union's ports.[10] The concept of launching a second Operation Overlord was rejected; it would involve fighting the Soviet forces where they were strongest, and far from their homeland. The possibility of recapturing Scandinavia was considered, but the logistical difficulties were great. The preferred course of action was therefore to attack the Dardanelles and Bosporus, and invade the Soviet Union via the Black Sea. The plan did not specifically call for the use of nuclear weapons, although it noted that bases within Boeing B-29 Superfortress range of key targets were lacking.[13] At the time the B-29 was the USAAF's most advanced long-range bomber.[14] There was no concept for operations beyond the initial counter-offensive, and the logistical implications of deploying a large force in the Middle East were not explored. Nonetheless, on 8 July 1946 the Joint Strategic Planners accepted Pincher as the basis for planning.[15]

The JWPC and the Joint Intelligence Committee (JIC) then produced a series of regional studies based upon Pincher. The first was Broadview, which was issued on 5 August, and revised on 24 October 1946. It dealt with the defense of North America. Long-range weapons meant that the heartland could no longer be considered invulnerable. In the immediate future, the Soviet Union was capable of conducting one-way air strikes and commando raids, and submarines could attack shipping and lay mines in American waters. The major threat, though, was seen as sabotage and subversion by Soviet agents. After 1950, there was a possibility the Soviet Union would develop nuclear weapons, and the long range aircraft or missiles to deliver them against cities in the United States. The possibility of an invasion of Alaska was also considered. To counter these threats, the United States would need mobile ground forces to counter raids, an air warning system, and antisubmarine forces.[16]

Plan Griddle, which was issued on 15 August 1946, dealt with the defense of Turkey. The Turkish Army was large, with 48 divisions, but it lacked modern equipment. The study estimated that the Soviet Union could deploy up to 110 divisions against Turkey without compromising operations elsewhere. A two-pronged advance was envisaged, with an attack on Eastern Thrace from Soviet-aligned Bulgaria, coupled with one into Anatolia from Soviet Transcaucasia. Airborne and amphibious forces could strike at both sides of the Dardanelles and Bosporus. From Turkey, Soviet forces could advance into Iraq and Iran. It was estimated that Turkey could hold out for at most 120 days before Turkish forces had to fall back to the western Anatolian coast. Nonetheless, Turkey figured large in American strategy as a potential base for air attacks on the Soviet Union, and blunting the Soviet drive into the Middle East. The study therefore called for increased military aid to Turkey, and development of Turkish airbases and ports.[17]

This led to the next study, which was issued on 2 November 1946. It was codenamed Caldron, and dealt with the Middle East. While the Soviet Union produced ample oil for its own peacetime needs, the planners felt that it had insufficient reserves for a major conflict, and therefore that seizing the oil resources of the Middle East would be a Soviet priority. Conversely, this would deny them to the Allies. The region was also considered as an important staging area for an attack on the Soviet Union, so it was expected that the Soviets would move to preclude that. Up to 85 Soviet divisions would be available for operations in the Middle East, where the British would have five divisions to stop them. Soviet forces were expected to reach Palestine within 60 days. About 14 Allied divisions could be concentrated in Egypt.[18][19]

Cockspur, a study of the threat to Italy, was dated 20 December 1946. It envisaged an attack on Italy by Yugoslav forces while Soviet forces concentrated on overrunning Germany, although once this was accomplished Soviet forces could then invade Italy from the north. The Allies had the option of trying to defend northern Italy, which was regarded as impractical, or conducting a fighting retreat. This raised the prospect of Allied forces there being overrun or destroyed, leaving nothing for the defense of Sicily. The study therefore recommended that the best course of action was to immediately withdraw to Sicily.[20]

Since the Pincher plan called for a withdrawal to the Pyrenees, the Iberian peninsula assumed considerable importance. Accordingly, Drumbeat, which was issued on 4 August 1947, dealt with its defense. It was estimated that Spain could mobilize 22 divisions in sixty days, but the quality of the Spanish Army was regarded as only fair. Portugal could mobilize another two divisions, and there were 5,000 British troops in Gibraltar. The JWPC did not believe that the Soviet Union would attack Spain, but the possibility was considered. It was estimated that as many as 20 Soviet divisions could reach the Pyrenees by D plus 45, and 50 by D plus 90. Nonetheless, the planners assessed that there was a chance that the Allies could hold Spain.[21]

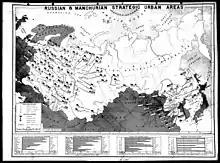

The Far East was considered a theater of secondary importance. Plan Moonrise, which covered it, was presented to the Joint Chiefs of Staff on 29 August 1947. It was estimated that the Soviet Union could deploy about 45 divisions in the region. Given the limitations of the Soviet Pacific Fleet, the Soviet Union's main target would be China. The Nationalist Chinese Army was large, but also largely ineffective, and the Soviet forces would be augmented by 1.115 million Chinese Red Army troops and 2 million militia, and perhaps three divisions from Mongolia, a Soviet satellite state. The first phase of a Soviet attack was expected to target the Port Arthur area. Manchuria would soon be overrun and Beijing would fall in about ten days. The planners estimated that Soviet forces could reach the Yellow River by D plus 90, and Nanjing and Hankou in another three weeks. An advance to the Yangtze River was not anticipated. At the time, US forces still garrisoned Korea, but the plan called for the American forces there to be withdrawn to Japan.[22]

Broiler (1947)

Although the Pincher studies were not accepted as a war plan by the Joint Chiefs of Staff, on 16 July 1947 the JWPC informed the Joint Staff Planners that sufficient progress had been made to formulate one.[19] On 29 August, the Joint Strategic Plans Committee (JSPC), which had replaced the JSP with the enactment of the National Security Act of 1947, instructed the Joint Strategic Plans Group (JSPG) to develop one based on Pincher, with the assumptions that a war would occur in 1948, that the United States would be allied with Britain and Canada, and that atomic weapons would be used.[23] The increased emphasis on atomic weapons represented an important change in emphasis.[24]

The resultant war plan was codenamed Broiler. Its starting point was estimates of the available strength of the US forces furnished by the three services; assessments of deficiencies would be based upon the plan at a later stage. The JSPG also drafted a longer-range war plan based on Broiler called Bushwacker, for a war starting on 1 January 1952, and one codenamed Charioteer, for one in 1955 that assumed that Western Europe had already been overrun and a strategic air campaign was called for. The planners had no political guidance as to what the ultimate objective of the war would be, so it was assumed that it would be to drive the Soviet Union back to its 1939 borders.[23]

The same scenario as Pincher was envisaged, and the Joint Intelligence Staff's assessment of Soviet Union's capabilities remained substantial: it could mobilize as many as 245 divisions. Of these, 120 could be deployed in Western Europe, 85 in the Balkans and Middle East, and 40 in the Far East. This gave it the capability of overrunning most of Europe in 45 days. In the longer term, the Soviet Union was expected to possess not just numerical superiority but technological equality as well. It was anticipated that the Soviet Union would have developed nuclear weapons by 1952, and long range bombers to deliver them to targets in the United States by 1956.[25]

To secure the United States, Greenland and Iceland would be occupied. The development of aerial refuelling capability would permit B-29 and the Boeing B-50 Superfortress, an improved version of the B-29, aircraft to attack twenty major urban areas in the Soviet Union.[26][27] B-29s were converted to Boeing KB-29 Superfortress aerial tankers, but the first planes were not delivered until late 1948; 77 would be in service by May 1950.[28] Major overseas bases would be established in the United Kingdom, Okinawa and Karachi; the Cairo-Suez and Basra areas were rejected as indefensible. The JSPG admitted that Karachi was far from ideal as a base, but at least it was defensible.[29]

The American mobilization plan, JCS 1725/1, submitted on 13 February 1947, was based on the assumption that nuclear weapons would not be used. It called for an Army of 13 divisions at the outbreak of hostilities, which would be increased to 45 divisions in a year, and 80 divisions in two years. This was similar to what had been achieved in World War II. In July the JWPC submitted a plan based on the use of nuclear weapons. On the assumption that between 100 and 200 nuclear weapons would be available, it called for 34 atomic bombs to be dropped on 24 Soviet cities; seven would be dropped on Moscow, three on Leningrad and two each on Kharkov and Stalingrad. It was reckoned that this would do massive damage to the Soviet Union's industries, and would kill or injure about one million of its citizens. The damage might well cause the Soviet Union to sue for peace.[30][31]

.jpg.webp)

The assumption that a hundred atomic bombs were available was not correct. The number of bombs in the stockpile was a closely-guarded secret in 1947. President Harry S. Truman was shocked when he was informed how small the stockpile really was.[32] By June 1948, components for about fifty Fat Man and two Little Boy bombs were on hand.[31] These were not whole and complete bombs, but components that had to be assembled by specially trained Armed Forces Special Weapons Project assembly teams known as special weapons units.[33] A well-trained team could assemble a bomb in two days, but the teams that had assembled the bombs during the war had returned to civilian life.[32] The first United States Army unit was formed in August 1947, followed by a second in December, and a third in March 1948.[33] Bomb components would have to be delivered to the assembly teams at forward bases by transport aircraft.[34]

In 1948, training of a United States Navy special weapons unit began, as the Navy foresaw the delivering of Little Boy nuclear weapons from its Midway-class aircraft carriers with Lockheed P2V Neptune and North American AJ Savage bombers.[35][36] An additional Army unit was created in May 1948, and two United States Air Force units in September and December 1948.[37] The Air Force gradually became the agency most concerned with the delivery of nuclear weapons, and by the end of 1949 it had twelve special weapons units, with another three in training, while the Army had four, and the Navy three, one for each of the three Midway-class carriers.[38] The Navy's claim to a role in strategic bombing caused friction with the Air Force.[36]

Only Silverplate B-29 bombers were capable of delivering Fat Man nuclear weapons, and of the 65 Silverplate B-29s that had been made, only 32 were still operational at the start of 1948, all of which were assigned to the 509th Bombardment Group, which was based at Roswell Army Airfield in New Mexico.[39][40] Trained crews were also in short supply; at the beginning of 1948 only six crews were qualified to fly atomic bombing missions, although enough personnel had been trained to assemble an additional fourteen crews in an emergency.[41] Up to 20 percent of the target cities were beyond the 3,000-nautical-mile (5,600 km) range of the B-29, requiring a one-way mission, which would expend the crew, bomb and aircraft. The Convair B-36 Peacemaker, with a range of 4,000 nautical miles (7,400 km), was in the process of being introduced to service in 1948, but was not atomic capable.[42] There were also doubts about the ability of the B-29 to penetrate Soviet air space; as a propeller-driven bomber it was no match for Soviet jet fighters, even at night.[43]

The forced reliance on nuclear weapons represented an important doctrinal change. During World War II, the USAAF had devastated Axis cities, but had clung to the doctrine of precision bombing even as it had drifted away in practice to area bombing; the latter had now become doctrine. One reason for this was the paucity of intelligence on the precise location of the Soviet Union's industrial facilities.[44][45] It was hoped that with the power of atomic bombs, just finding the right cities would be good enough.[31]

_1955.jpg.webp)

However, this was far from certain. In January 1949, Lieutenant General Curtis LeMay, who assumed command of the Strategic Air Command (SAC) in October 1948, ordered a practice attack on the Wright-Patterson Air Force Base as an exercise. A similar exercise had been conducted in May 1947, when 101 B-29s were ordered to attack New York; 30 had not left the ground due to mechanical problems. This time, the crews were ordered to attack at combat altitude of 30,000 feet (9,100 m) rather than the customary 10,000 to 15,000 feet (3,000 to 4,600 m), which was warmer and did not require cabin pressurization or the use of oxygen masks, and at night, using radar bombing techniques. They were given 1938 maps of Dayton, Ohio, which while old, were better than the ones they had of the Soviet Union. The high altitude and cold temperatures took their toll on aircraft and crews alike. Many sorties were cancelled due to freezing rain, and the radar had difficulty locating targets due to ground clutter and thunderstorm activity. Of the 303 simulated attacks on the target, two-thirds were more than 7,000 feet (2,100 m) from the target, and the average error was 10,000 feet (3,000 m). The atomic bombs of the era would have left the target unscathed.[46][47] LeMay said "Not one airplane finished that mission as briefed. Not one".[48]

When the Joint Logistics Committee (JLC) studied the plan, it assessed that the Mediterranean line of communications to the Cairo-Suez area would require 912 ships after six months. If the Mediterranean were closed, the longer route around the Cape of Good Hope and the Red Sea would call for 1,042 ships. Over two years the need would rise to 2,252 and 3,848 ships respectively. On 2 September 1947, after a more detailed examination of requirements, the figure for support via the Red Sea after six months was raised from 1,042 to 1,788 ships. The JLC calculated that it would take 16 months to reactivate so many mothballed cargo ships. Allied forces would require 32,360 short tons (29,360 t) of supplies per day, but the combined capacity of the Red Sea ports was only 26,400 short tons (23,900 t).[49][50]

A 14 October 1947 assessment of aircraft requirements for the first twelve months came to 91,332 aircraft of all types, but a month later the Munitions Board (the successor to the Army-Navy Munitions Board under the National Security Act of 1947) reported that this was unrealistic. The JLC assessed the mobilization requirements as unrealistic too, as they would require 300,000 men per month to be inducted, which would put enormous strain on the training and logistical infrastructure.[49][50] On 23 January 1948, the Munitions Board reported that Broiler and Charioteer called for resources that were not available. It was estimated that the stockpiling of equipment and activation of standby munitions plants would require $139.6 million in fiscal year 1949 (equivalent to $1367 million in 2022), but only $37.6 million (equivalent to $368 million in 2022) was available. It recommended that a more realistic war plan be drafted.[51]

The JSPC presented Broiler to the Joint Chiefs of Staff on 10 March 1948. A slightly modified version, codenamed Frolic, was forwarded to the Secretary of Defense, James Forrestal.[23] Although Broiler was accepted as an emergency war plan, all the Joint Chiefs had reservations about it.[52][53] The Chief of Staff to the Commander in Chief, Fleet Admiral William D. Leahy, did not like the reliance on the use of nuclear weapons when it was uncertain that their use would be authorized. The Chief of Naval Operations, Admiral Louis E. Denfeld, did not agree with the concept of abandoning Western Europe, which he argued was contrary to the foreign policy and national objectives of the United States. He contended that a better strategy would be to build up US forces in Europe to the point that a stand could be made on the Rhine.[52][53]

Halfmoon (1948)

By 1948, the United States had become enmeshed in great power politics. At the same time, severe limitations on defense spending created an ever-widening gap between capabilities and obligations. Western Europe remained weak and divided, and China was wracked with the Chinese Civil War.[54] Planners from the United States, Britain and Canada met in Washington, D.C., from 12 to 21 April 1948, and they drew up an outline emergency war plan based on Broiler.[55]

This resulted in a new plan called Halfmoon (renamed Fleetwood in August 1948). The number of countries assumed to be on the Allied side was increased. It was assumed that the British Commonwealth, the Western Union countries (France, Belgium, the Netherlands and Luxembourg), and the entire Western Hemisphere would be allies of the United States, and that Turkey, Spain, Norway, Iraq, Iran, Pakistan, Afghanistan, Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Jordan, Syria, Lebanon, and Yemen would become allies if attacked by the Soviet Union. At the insistence of the British that it was feasible to hold the Cairo-Suez area, a base there was substituted for the one in Karachi, although the Americans retained the latter as a back up. A strategic air offensive would be launched with B-36 bombers from the United States and B-29 and B-50 bombers based in the United Kingdom, Cairo-Suez and Okinawa.[55]

Halfmoon assumed that atomic bombs would be used from the outset by the United States, and by the Soviet Union too once it had developed them. US intelligence (incorrectly) assessed that this would not be in 1949.[55] In the absence of adequate conventional forces, the planners felt that they had no alternative.[56] The President, Harry S. Truman, was briefed on Halfmoon on 6 May 1948, and he expressed misgivings. He asked Leahy to prepare an alternative plan to "resist a Russian attack without using atomic bombs for the reason that we might not have them available either because they might at that time be outlawed or because the people of the United States might not at the time permit their use for aggressive purposes."[57]

The Secretary of the Army, Kenneth C. Royall, was particularly disturbed by Truman's objection, and circulated a memo on 19 May calling for a review of national policy regarding the use of nuclear weapons. He raised the matter at a National Security Council (NSC) meeting the next day chaired by the Secretary of State, George C. Marshall,[58] who considered Truman's policy of resisting the Soviet Union without the means to do so was "playing with fire while we have nothing with which to put it out."[59] In July Forrestal told the Joint Chiefs to ignore the President's request for an alternative plan.[58] The policy that Royall called for was drafted by the Air Force in July, updated with minor revisions in early September, and adopted by the NSC as NSC 30 on 16 September. It stated that:

12. It is recognized that, in the event of hostilities, the National Military Establishment must be ready to utilize, promptly and effectively all appropriate means available, including atomic weapons, in the interests of national security and must therefore plan accordingly.

13. The decision as to the employment of atomic weapons in the event of war is to be made by the Chief Executive when he considers such decision to be required.[60]

Thus, after three years, the inclusion of nuclear weapons in war plans was officially authorized. While the president remained the sole authority on their use, the selection of targets and the circumstances in which they would be used was in the hands of the planners.[60] An updated version of Halfmoon was issued on 28 January 1949 called Trojan. This contained an annex detailing the strategic air offensive. This would target 70 Soviet cities with 133 nuclear weapons, of which eight would be dropped on Moscow and seven on Leningrad.[55] The main change from Fleetwood was the addition of Greece, Italy, Iceland, Ireland, the Philippines and Switzerland to the list of allies, but at the same time dropping the assumption that Arab countries would be on the Allied side, due to the deterioration of relations with the United States in the wake of the 1948 Arab–Israeli War and the creation of the state of Israel.[55][61]

The JLC used Halfmoon as the basis for a new mobilization plan called Cogwheel in response to a request from the Secretary of Defense to provide details that could be used by the Munitions Board as a basis for industrial mobilization. Cogwheel detailed the requirements of the war plan for the first two years, assuming a start of hostilities on 1 July 1949. The only point of disagreement among the three services concerned the construction of additional aircraft carriers; the Army and Air Force believed that the Navy had sufficient on hand or in mothballs, and the additional carriers could not be completed in two years, by which time the Army and Air Force would have completely mobilized. This was submitted on 1 September 1948. On 6 December the Joint Chiefs of Staff ordered the three services to prepare revised mobilization plans. Before this could occur, the Munitions Board submitted its assessment of Cogwheel. It concluded that aircraft production would be 60 percent of requirements by the end of the first year. Further, it was assessed that demand for raw materials such as copper and aluminum would exceed supply, that those for munitions exceeded the capacity to produce them, and that the call for manpower exceeded the ability of the Selective Service System to process them. The Munitions Board therefore decided to base its planning on 50 percent of the requirements of Cogwheel.[62][63]

| Force | At start | After one year | After two years |

|---|---|---|---|

| Army divisions | 20 | 40 | 80 |

| Air Force groups | 66 | 103 | 186 |

| Navy warships | 510 | 1,785 | 2,976 |

| Navy aircraft carriers | 11 | 16 | 25 |

On 4 October 1948, Denfeld told the Senate Armed Services Committee:

The unpleasant fact remains that the Navy has honest and sincere misgivings as to the ability of the Air Force successfully to deliver the [atomic] weapon by means of unescorted missions flown by present-day bombers, deep into enemy territory in the face of strong Soviet air defenses, and to drop it on targets whose locations are not accurately known.[64]

The Joint Chiefs of Staff approved Trojan on 28 January 1949, but recognized that it fell short of a war plan that could be implemented.[55] General Omar N. Bradley, the Chief of Staff of the United States Army, admitted that the Army had serious deficiencies of both personnel and equipment that it was unable to correct due to budget limitations. Similarly, Denfeld reported that the Navy did not have the resources to carry out its part, and the Chief of Staff of the United States Air Force, General Hoyt Vandenberg stated that the Air Force did not have the means to conduct Trojan.[65] The Joint Chiefs of Staff estimated that $29 billion (equivalent to $281 billion in 2022) was required for fiscal year 1950, but the administration would only support $17 to $18 billion (equivalent to $165 billion to $175 billion in 2022).[66]

Offtackle (1949)

On 25 February 1949, the acting Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, General of the Army Dwight D. Eisenhower issued a directive providing more guidance for the strategic planners. He accepted that the Rhine could not be held with the available forces, but wanted a return to Western Europe at the earliest possible date. Over the next seven months, a new plan called Offtackle was drawn up. This was followed by a second round of planning conferences with British and Canadian representatives from 26 September to 4 October. For the first time, some political guidance was available from the National Security Council in the form of NSC 20/4. It stated that the policy of the United States would not initiate war with the Soviet Union, but a conflict could result from a miscalculation on the part of the Soviet Union, such as an underestimation of American resolve. In this, it affirmed an assumption that had already been built into the war plans from Pincher on. It also informed the Joint Chiefs that in the event of war with the Soviet Union, it would not be required to force an unconditional surrender or to conduct an occupation. Like previous war plans, Offtackle only dealt with the opening stages of the war and not with the concluding stages or post-conflict issues.[67]

The strategic air campaign outlined in Offtackle was even more ambitious than Trojan. The campaign called for the delivery of 292 atomic bombs and 246,900 short tons (224,000 t) of conventional bombs. It was estimated that 85 percent of the industrial targets would be completely destroyed. These included electric power, shipbuilding, petroleum production and refining, and other essential war fighting industries. Moreover, it was hoped that the campaign would not just cripple Soviet industry, but loosen the control of the government over the people, undermine the determination to prosecute the war, disrupt mobilization, and retard the advance of Soviet ground forces into Western Europe.[67][68] However, SAC lacked the resources to implement the plan. With its available aircraft, it could carry out only 2,000 sorties in the first two months, far short of the 6,000 called for in the plan. Supporting them would require 360 Douglas C-54 Skymaster sorties or their equivalent, but only 260 were allocated to SAC. Spare parts for the B-50s were in short supply, and the amount of avgas in the war reserve was insufficient.[69]

The first steps towards developing an alliance of western countries for an organized and coordinated defense came with the formation of the Western Union on 17 March 1948. This was a mutual defensive alliance consisting of the United Kingdom, France, Belgium, the Netherlands, and Luxembourg.[70] It was followed by the formation of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) on 4 April 1949. On 6 October 1949, Truman signed into law the Mutual Defense Assistance Act, which provided $1 billion (equivalent to $10 billion in 2022) for NATO allies to purchase weapons and equipment.[71] The American ground forces consisted of one division and three regiments in Europe, and five divisions in the United States. The whole NATO alliance could field ten divisions in West Germany, but it was estimated that at least eighteen were required to halt a Soviet advance on the Rhine.[72] Despite misgivings, in December 1949 the twelve NATO allies accepted a common defense plan.[73]

To fulfil Eisenhower's directive, the planners considered other options. The main ones were to fall back to the Pyrenees and hold there, or to mount an Operation Overlord–style invasion of Soviet-occupied Western Europe from North Africa or the United Kingdom. The forces for the former were lacking, so the latter strategy was adopted.[67][68] Field Marshal Lord Montgomery, the Chairman of the Commanders-in-Chief Committee of the Western European Union, reported on 15 June 1950 that "as things stand today and in the foreseeable future, there would be scenes of appalling and indescribable confusion in Western Europe if we were ever attacked by the Russians."[74] He felt that NATO forces were incapable of holding the Rhine, and sought a new directive; in the end the Western European Union ordered him to hold the Rhine.[75]

Forrestal expressed doubts about the plan, which he thought relied too much on the Soviets doing what they were expected to do. He questioned whether strategic bombardment could win a war. Before he committed to the purchase of millions of dollars worth of aircraft, he wanted some assurances. An interservice committee chaired by Lieutenant General Hubert R. Harmon, USAF, was formed to investigate. The report reiterated that in the absence of adequate conventional forces, the strategic air campaign was all that there was. It estimated that it would result in a 30 to 40 percent decrease in Soviet industrial capacity. About 6.7 million casualties were anticipated, of whom 2.7 million would be killed. The survivors would face life without electric power or fuel. Nonetheless, the Harmon committee doubted that it would destroy civilian morale; based on World War II experience, the opposite would be more likely. A separate question, left unanswered, was whether it could be successfully conducted, given the poor state of intelligence regarding the Soviet Union.[76][77] Denfeld, for one, doubted that it could, and proposed that instead a tactical air campaign be conducted to retard the Soviet advance into Western Europe.[78] The Air Force pressed ahead with procurement of the long-range B-36 bomber, which led to a confrontation between the Navy and the Air Force known as the Revolt of the Admirals, and to the relief of Denfeld, who was replaced by Admiral Forrest Sherman.[79]

Outcome

Interservice conflict was relieved by the outbreak of the Korean War and the consequent increase in the defense budget from $14.258 billion in fiscal year 1950 (equivalent to $138 billion in 2022) to $53.208 billion in fiscal year 1951 (equivalent to $483 billion in 2022) and $65.992 billion in fiscal year 1952 (equivalent to $587 billion in 2022). This allowed the Joint Chiefs of Staff to contemplate a 21-division Army, 143-wing Air Force and 402-ship Navy.[80] The Soviet Union's detonation of its first atomic bomb in August 1949—a year before the earliest date that the Joint Intelligence Committee had assessed as possible and four years earlier than the date it regarded as most probable on 22 March 1948—led to a revision of estimates of the Soviet nuclear stockpile. It was now expected to have 10 to 20 bombs by mid-1950, 45 to 90 by mid-1952, and 120 to 200 by mid-1954.[81] This was immediately incorporated into the next draft of the Offtackle war plan dated 25 October. Both sides were assumed to use nuclear weapons from the commencement of hostilities.[81] The United States now had to contemplate the air defense of North America. On 30 March 1949, Truman signed into law legislation authorizing the establishment of 75 radar stations at a cost of $85.5 million (equivalent to $829 million in 2022). No money was appropriated, so only some site selection had been carried out by January 1950.[82]

The Operation Sandstone nuclear tests in April and May 1948 had demonstrated improved designs, with the X-Ray and Yoke tests having yields of 37 kilotons of TNT (150 TJ) and 41 kilotons of TNT (170 TJ) respectively—nearly twice that of the older Mark 3 Fat Man devices in the inventory. The new Mark 4 nuclear bomb, which entered service in March 1949,[83] was a more practical piece of ordnance than its predecessor, and its composite uranium-plutonium core made more economical use of the available fissile material. In May 1948, the Los Alamos Scientific Laboratory commenced work on the design of the Mark 5 nuclear bomb, a smaller and lighter weapon.[84] The development of Soviet atomic bombs provided the impetus for the development of even more destructive thermonuclear weapons.[85] On 31 December 1949, the Strategic Air Command had 521 B-29s, B-36s and B-50s capable of delivering atomic bombs. It was estimated that SAC bombers would suffer 35 percent casualties at night, and fifty percent if missions had to be conducted in daylight. The delivery of the 292 atomic bombs called for by the Offtackle plan was regarded as practical, but there would be no ability to launch follow-up raids.[86] A jet bomber, the Boeing B-47 Stratojet was under development, but would not become operational until 1953.[87] The concept of nuclear deterrence did not figure in the war plans; nuclear weapons were seen purely as weapons of war.[88]

In 1947 the United States European Command (EUCOM) ordered the sole American division stationed in Europe, the 1st Infantry Division, which was scattered about the US Occupation Zone in West Germany, to reassemble to constitute a theater reserve. It was relieved of its occupation duties and its commander, Major General Frank W. Milburn, was ordered to resume its tactical training. By 1950, it was still scattered, while EUCOM looked for suitable locations for its consolidation.[6] To build up the US ground forces, the Joint Chiefs decided to deploy four more divisions to Europe in 1951. Plans for the defense of the Rhine were still regarded as unsound as NATO was short 8,000 tanks, 9,200 half-tracks and 3,200 artillery pieces.[89] Equipment that had been purchased during World War II was increasingly becoming obsolescent or unserviceable. The commander of the Army's Logistics Division, Major General Henry S. Aurand, reported in September 1948 that the Army had 15,526 tanks, but only 1,762 were serviceable.[90] By June 1950, four hundred M26 Pershing tanks had been rebuilt as the new M46 Patton.[91]

The war plans of the late 1940s were never put to the test. It is not known whether the Soviet Union would have overrun Western Europe, whether the strategic air offensive would have succeeded, or even who precisely would have won such a war.[88] The disparity between military means and political commitments weighed heavily on the planners.[92] They concentrated on Soviet capabilities rather than intentions. The assessment of the intent of the Soviet Union was that it did not want to risk a war due to the devastated state of its economy. A calculated risk was taken on that basis.[88] "As long as we can outproduce the world, can control the sea and strike inland with the atomic bomb," Forrestal noted in December 1947, "we can assume certain risks otherwise unacceptable in an effort to restore world trade, to restore the balance of power-military power and to eliminate some of the conditions that breed war."[93]

See also

Notes

- ↑ Ross 1988, p. 4.

- ↑ Schnabel 1996, pp. 7–8.

- ↑ Ross 1988, pp. 4–5.

- ↑ Schnabel 1996, pp. 91–97.

- ↑ Schnabel 1996, p. 109.

- 1 2 Carter 2015, p. 8.

- ↑ Carter 2015, pp. 148–149.

- ↑ Schnabel 1996, pp. 63–65.

- ↑ Rearden 2012, p. 95.

- 1 2 3 4 Schnabel 1996, pp. 71–72.

- ↑ Ross 1988, pp. 31–33.

- ↑ Ross 1988, p. 27.

- ↑ Ross 1988, pp. 27–30.

- ↑ Moody 1995, p. 49.

- ↑ Schnabel 1996, p. 74.

- ↑ Ross 1988, pp. 34–35.

- ↑ Ross 1988, pp. 35–36.

- ↑ Ross 1988, pp. 36–38.

- 1 2 Schnabel 1996, p. 75.

- ↑ Ross 1988, pp. 38–40.

- ↑ Ross 1988, pp. 41–43.

- ↑ Ross 1988, pp. 43–48.

- 1 2 3 Condit 1996, pp. 153–154.

- ↑ Herken 1980, pp. 226–227.

- ↑ Ross 1988, pp. 53–54.

- ↑ Moody 1995, pp. 54–55.

- ↑ Ross 1988, pp. 83–84.

- ↑ Curatola 2016, pp. 119–120.

- ↑ Ross 1988, p. 87.

- ↑ Ross 1988, pp. 54–57.

- 1 2 3 Curatola 2016, pp. 106–107.

- 1 2 Herken 1980, pp. 196–197.

- 1 2 Abrahamson & Carew 2002, pp. 67–69.

- ↑ Moody 1995, p. 60.

- ↑ Abrahamson & Carew 2002, p. 114.

- 1 2 Curatola 2016, pp. 69–71.

- ↑ Abrahamson & Carew 2002, p. 153.

- ↑ Brahmstedt 2002, p. 71.

- ↑ Little 1955, pp. 391–392.

- ↑ Campbell 2005, pp. 61–62.

- ↑ Moody 1995, p. 169.

- ↑ Curatola 2016, pp. 108–109.

- ↑ Knaack 1988, p. 490.

- ↑ Herken 1980, pp. 218–219.

- ↑ Curatola 2016, pp. 103–105.

- ↑ Borowski 1982, p. 167.

- ↑ Curatola 2016, pp. 135–137.

- ↑ Rhodes, Richard (11 June 1995). "The General and World War III". The New Yorker. ISSN 0028-792X. Retrieved 30 November 2023.

- 1 2 Ross 1988, pp. 58–59.

- 1 2 3 Condit 1996, p. 164.

- ↑ Ross 1988, p. 80.

- 1 2 Condit 1996, p. 155.

- 1 2 Ross 1988, pp. 72–74.

- ↑ Ross 1988, pp. 79–81.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Condit 1996, pp. 156–159.

- ↑ Ross 1988, p. 91.

- ↑ Williamson & Rearden 1993, p. 85.

- 1 2 Williamson & Rearden 1993, pp. 85–86.

- ↑ Condit 1996, p. 11.

- 1 2 Williamson & Rearden 1993, pp. 90–91.

- ↑ Curatola 2016, pp. 111–112.

- ↑ Condit 1996, pp. 164–165.

- ↑ Ross 1988, pp. 95–96.

- ↑ Curatola 2016, p. 32.

- ↑ Ross 1988, pp. 98–99.

- ↑ Toprani 2019, p. 129.

- 1 2 3 Condit 1996, pp. 159–162.

- 1 2 Curatola 2016, pp. 116–119.

- ↑ Curatola 2016, p. 121.

- ↑ Condit 1996, p. 191.

- ↑ Carter 2015, p. 6.

- ↑ Ross 1988, pp. 138–139.

- ↑ Carter 2015, pp. 6–7.

- ↑ Poole 1998, p. 96.

- ↑ Poole 1998, p. 99.

- ↑ Condit 1996, pp. 169–172.

- ↑ Curatola 2016, pp. 125–126.

- ↑ Condit 1996, pp. 183–185.

- ↑ Condit 1996, pp. 185–188.

- ↑ Ross 1988, p. 139.

- 1 2 Condit 1996, pp. 280–281.

- ↑ Condit 1996, p. 287.

- ↑ Sandia National Laboratory 1967, p. 8.

- ↑ Curatola 2016, pp. 60–62.

- ↑ Condit 1996, pp. 291–293.

- ↑ Ross 1988, pp. 139–140.

- ↑ Curatola 2016, p. 129.

- 1 2 3 Ross 1988, p. 155.

- ↑ Ross 1988, p. 142.

- ↑ Converse 2012, p. 171.

- ↑ Converse 2012, p. 177.

- ↑ Condit 1996, p. 13.

- ↑ Rearden 1984, p. 424.

References

- Abrahamson, James L.; Carew, Paul H. (2002). Vanguard of American Atomic Deterrence. Westport, Connecticut: Praeger. ISBN 978-0-275-97819-8. OCLC 49859889.

- Borowski, Harry R. (1982). A Hollow Threat: Strategic Air Power and Containment Before Korea. Contributions in Military History. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-313-22235-1. OCLC 836244900.

- Brahmstedt, Christian (2002). Defense's Nuclear Agency, 1947–1997 (PDF). DTRA history series. Washington, D.C.: Defense Threat Reduction Agency, US Department of Defense. OCLC 52137321. Retrieved 9 August 2020.

- Campbell, Richard H. (2005). The Silverplate Bombers: A History and Registry of the Enola Gay and Other B-29s Configured to Carry Atomic Bombs. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company. ISBN 978-0-7864-2139-8. OCLC 58554961.

- Carter, Donald A. (2015). Forging the Shield: The U.S. Army in Europe, 1951–1962 (PDF). Washington, D.C.: Center of Military History, United States Army. ISBN 978-0-16-092754-6. OCLC 931745874. Retrieved 12 August 2020.

- Condit, Kenneth W. (1996). The Joint Chiefs of Staff and National Policy, Volume II: 1947–1949 (PDF). History of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. Washington, D.C.: Office of Joint History Office of the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. OCLC 4651413. Retrieved 30 April 2020.

- Converse, Elliott Vanveltner (2012). Rearming for the Cold War, 1945–1960 (PDF). History of Acquisition in the Department of Defense. Washington, D.C.: Historical Office, Office of the Secretary of Defense. ISBN 978-0-16-091132-3. OCLC 793093436. Retrieved 12 August 2020.

- Curatola, John M. (2016). Bigger Bombs for a Brighter Tomorrow: The Strategic Air Command and American War Plans at the Dawn of the Atomic Age, 1945–1950. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-9419-4. OCLC 927620067.

- Herken, Gregg (1980). The Winning Weapon: The Atomic Bomb and the Cold War 1945–1950. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 978-0-394-50394-3. OCLC 251501723.

- Knaack, Marcelle Size (1988). Encyclopedia of U.S. Air Force Aircraft and Missile Systems: Volume II: Post-World War II Bombers, 1945–1973 (PDF). Washington, D.C.: Office of Air Force History. ISBN 978-0-912799-59-9. OCLC 631301640. Retrieved 5 May 2020.

- Little, Robert D. (1955). Foundations of an Atomic Air Force and Operation Sandstone 1946–1948 (PDF). The History of Air Force Participation in the Atomic Energy Program, 1943–1953. Vol. II. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Air Force, Air University Historical Liaison Office. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 28 July 2013.

- Moody, Walton S. (1995). Building a Strategic Air Force (PDF). Washington, D.C.: Air Force History and Museums Program. OCLC 1001725427. Retrieved 2 May 2020.

- Poole, Walter S. (1998). The Joint Chiefs of Staff and National Policy 1950–1952 (PDF). History of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. Vol. IV. Washington, D.C.: Office of Joint History Office of the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. OCLC 45517053. Retrieved 29 August 2020.

- Rearden, Steven L. (1984). The Formative Years 1947–1950 (PDF). History of the Office of the Secretary of Defense. Washington, D.C.: Historical Office, Office of the Secretary of Defense. OCLC 1096666315. Retrieved 14 September 2020.

- Rearden, Steven L. (2012). Council of War: History of the Joint Chiefs of Staff (PDF). Washington, D.C.: National Defense University Press. OCLC 808500560. Retrieved 22 March 2023.

- Ross, Steven T. (1988). American War Plans 1945–1950. New York and London: Garland. ISBN 978-0-8240-0207-7. OCLC 242582147.

- The History of the Mark 4 Bomb. Albuquerque, New Mexico: Sandia National Laboratory. 1967. Retrieved 12 August 2020.

- Schnabel, James F. (1996). The Joint Chiefs of Staff and National Policy 1945–1947 (PDF). History of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. Vol. I. Washington, D.C.: Office of Joint History Office of the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. OCLC 227843704. Retrieved 30 April 2020.

- Toprani, Anand (2019). "Budgets and Strategy: The Enduring Legacy of the Revolt of the Admirals". Political Science Quarterly. 134 (1): 117–146. doi:10.1002/polq.12870. ISSN 0032-3195. S2CID 159326841. Retrieved 12 August 2020.

- Williamson, Samuel R. Jr.; Rearden, Steven L. (1993). The Origins of U.S. Nuclear Strategy. New York: St Martin's Press. ISBN 978-0-312-08964-1. OCLC 899218592.