| Urasoe Castle 浦添城 | |

|---|---|

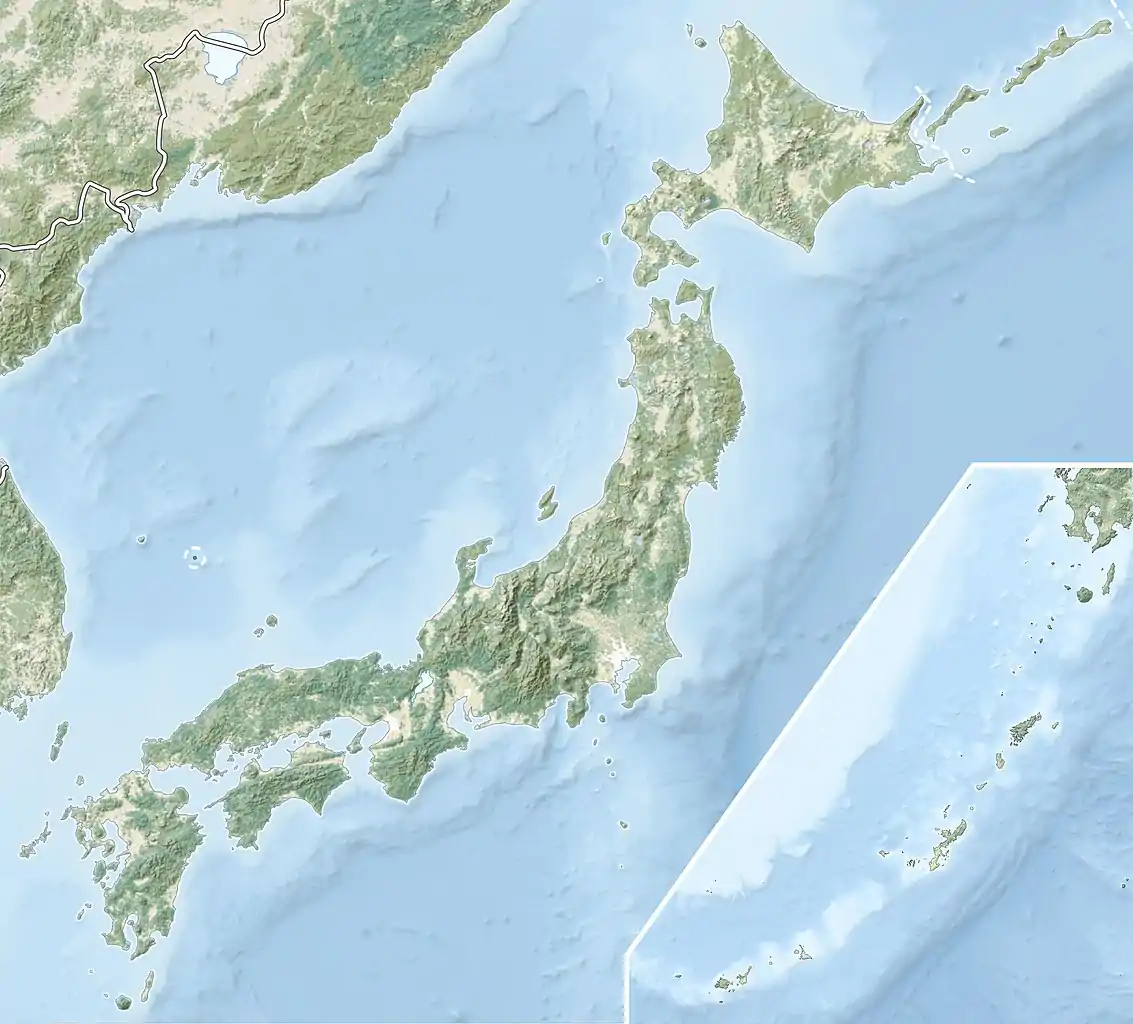

| Urasoe, Okinawa, Japan | |

Outer walls of Urasoe Castle | |

Urasoe Castle 浦添城  Urasoe Castle 浦添城 | |

| Type | Gusuku |

| Site information | |

| Controlled by | Chūzan (late 13th century - 1429) |

| Condition | Ruins |

| Site history | |

| Built | late 13th – early 14th century; later expanded and refurbished |

| In use | late 13th century – 1609 |

| Materials | Ryukyuan limestone, wood, ceramic roof tiles |

| Demolished | 1609 invasion of Ryukyu |

| Battles/wars | Invasion of Ryukyu (1609) |

| Garrison information | |

| Occupants | Kings of Chūzan, incl. Eiso (r. 1260–1299) |

Urasoe Castle (浦添城, Urasoe jō, Okinawan: Urashii Gushiku[1]) is a Ryukyuan gusuku which served as the capital of the medieval Okinawan principality of Chūzan prior to the unification of the island into the Ryukyu Kingdom, and the moving of the capital to Shuri. In the 14th century, Urasoe was the largest castle on the island, but today only ruins remain.

Description

The castle ruins lie behind the modern city of Urasoe, on the northern edge of Naha, today the capital of Okinawa Prefecture. It sits roughly 130-140m above sea level, and consists of two sections, arranged for the most part along a northwest–southeast axis. The Kogusuku (old castle) and Migusuku together cover an area roughly 380m long by 60-70m wide, the kogusuku being on a slightly higher rise to the east of the migusuku. A series of interconnected enclosures cross the site from east–west. As much of the site has been extensively damaged, both historically and more recently, the overall size, layout and structure of the castle is difficult to ascertain, along with many other aspects of its history and use.

A series of four separate ramparts and palisades defended the lower portion of the castle, along with a moat that has been dated to the late 14th or early 15th century. The upper portion of the castle, like many other gusuku, was situated in such a way that it was sufficiently defended by sheer cliffs and the sea and likely lacked significant defensive walls or ramparts.

The oldest Buddhist temples in Okinawa, the Ryufuku-ji and Gokuraku-ji, are nearby, along with Urasoe yōdore, the site of the royal mausolea of several kings of Chūzan, dug directly into the cliffside.

King Eiso (r. 1260–1299) ruled Chūzan from Urasoe, and is entombed near the northwest cliff of the castle. His mausoleum contains three stone coffins from China, possibly from Fujian; it is believed that Eiso is buried in the largest one, his father and grandfather in the other two. The coffins are decorated with birds, flowers, deer, shishi (lion-dogs), and various Buddhist images, along with dragons and phoenixes on the lids, which are designed to look like tiled roofs. Eiso lived in the 13th century, however, based on the style of designs and decorations on the coffins, archaeologists believe these to be of later, 15th-century, construction. King Shō Nei (r. 1597–1620), is also entombed here.

Excavations in the last decades of the 20th century uncovered a ceremonial path leading from the castle to the tombs, along with the remains of an artificial lake, a tunnel entrance to the castle, and a series of residences believed to have belonged to a noble family. Over 30,000 artifacts were recovered from these excavations.

History

As royal capital, Urasoe represents the first instance of a major shift in the construction of elite structures, and castles (gusuku) in particular, in Okinawa. It is believed to have been grander in scale and complexity than sites which came before. Most of what is known about the castle's history comes from archaeological excavations, and not from narrative historical documentation.

Low stone walls and post-holes indicate the original form of the castle, constructed in the late 13th–early 14th centuries. Over the next century or so, the castle was expanded, and came to encompass what is today labeled the kogusuku. Korean roof tiles were used in the expansions and construction at this time. Significant portions of the castle were taken away in the early 16th century to aid in the construction of Shuri Castle. The castle remained in use, however, and Shō Iko, the son of King Shō Shin, took up residence there in 1509. Finding it largely in ruins, he oversaw its refurbishment, and it is believed he moved the residential section of the castle from the kogusuku to the migusuku at this time.

The castle was burned and destroyed in the 1609 invasion of Ryukyu by Satsuma, along with the Ryufuku-ji temple which sat below it on the hillside. The castle and the ridge it was built upon were also a Japanese defensive position during the Battle of Okinawa. Desmond Doss earned his Medal of Honor by lowering injured men down the cliff on the North side of the castle.

Many scholars have traditionally seen the establishment of Shuri as royal capital as bringing with it great changes and developments in the representation of the monarchy. However, some scholars today believe that "the form for the royal capital at Shuri, which included a central palace (seiden), a plaza for gathering allied elites and subjects, a ritual area, a large external pond, and attached Buddhist temples, was already complete at Urasoe".[2] Archaeologists point out in particular the wealth, power, and aesthetic grandeur indicated by elements of the site's structures. Roof tiles and other items, mostly ceramics, were imported from Korea, and stone coffins carved in the Chinese style, likely in Fujian, were also imported, indicating the tiny kingdom's extensive trade and diplomatic connections; items from Korea, in particular, are known to have been quite rare and expensive in Okinawa for many centuries, and have been excavated only in the most elite of sites. The Buddhist temples on the site indicate strong political and cultural connections to Japan, and the large pond or lake below the castle is a common symbol of elite power and prestige throughout East Asia.

References

Sources

- Pearson, Richard (2001). "Archaeological Perspectives on the Rise of the Okinawan State." Journal of Archaeological Research, Vol 9, No 3. pp270–271.