| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

3,3′-[(4S,16S)-3,18-Diethyl-2,7,13,17-tetramethyl-1,19-dioxo-1,4,5,15,16,19,22,24-octahydro-21H-biline-8,12-diyl]dipropanoic acid | |

| Systematic IUPAC name

3,3′-([12S,4(52)Z,72S]-13,74-Diethyl-14,33,54,73-tetramethyl-15,75-dioxo-12,15,72,75-tetrahydro-11H,31H,71H-1,7(2),3,5(2,5)-tetrapyrrolaheptaphan-4(52)-ene-34,53-diyl)dipropanoic acid | |

| Other names

Urochrome | |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol) |

|

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.015.870 |

| MeSH | Urobilin |

PubChem CID |

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA) |

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C33H42N4O6 | |

| Molar mass | 590.721 g·mol−1 |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

Infobox references | |

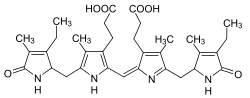

Urobilin or urochrome is the chemical primarily responsible for the yellow color of urine. It is a linear tetrapyrrole compound that, along with the related colorless compound urobilinogen, are degradation products of the cyclic tetrapyrrole heme.

Metabolism

Urobilin is generated from the degradation of heme, which is first degraded through biliverdin to bilirubin. Bilirubin is then excreted as bile, which is further degraded by microbes present in the large intestine to urobilinogen. The enzyme responsible for the degradation is the recently discovered bilirubin reductase. Some of this remains in the large intestine, and its conversion to stercobilin gives feces their brown color. Some is reabsorbed into the bloodstream and then delivered to kidney. When urobilinogen is exposed to air, it is oxidized to urobilin, giving urine its yellow color.[1]

Importance

Many urine tests (urinalysis) monitor the amount of urobilin in urine, as its levels can give insight on the effectiveness of urinary tract function. Normally, urine would appear as either light yellow or colorless. A lack of water intake, for example following sleep or dehydration, reduces the water content of urine, thereby concentrating urobilin and producing a darker color of urine. Obstructive jaundice reduces biliary bilirubin excretion, which is then excreted directly from the blood stream into the urine, giving a dark-colored urine but with a paradoxically low urobilin concentration, no urobilinogen, and usually with correspondingly pale faeces. Darker urine can also be due to other chemicals, such as various ingested dietary components or drugs, porphyrins in patients with porphyria, and homogentisate in patients with alkaptonuria.

See also

References

- Voet and Voet Biochemistry Ed 3 page 1022

- Nelson, L., David, Cox M.M., .2005. “Chapter 22- Biosynthesis of Amino Acids, Nucleotides, and Related Molecules”, pp. 856, In Lehninger Principles of Biochemistry. Freeman, New York. pp. 856

- Bishop, Michael, Duben-Engelkirk, Janet L., and Fody, Edward P. "Chapter 19, Liver Function, Clinical Chemistry Principles, Procedures, Correlations, 2nd Ed." Philadelphia: copyright 1992 J.B. Lippincott Company.

- Munson-Ringsrud, Karen and Jorgenson-Linné, Jean "Urinalysis and Body Fluids, A ColorText and Atlas." St. Louis: copyright 1995 Mosby