| |

| Observation data Epoch J2000.0 Equinox J2000.0 | |

|---|---|

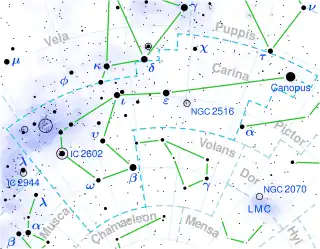

| Constellation | Carina |

| Right ascension | 11h 08m 35.39s[1] |

| Declination | −58° 58′ 30.1″[1] |

| Apparent magnitude (V) | +3.83[2] (3.84 - 4.02[3]) |

| Characteristics | |

| Spectral type | G0-4-Ia+[4] |

| U−B color index | +0.96[2] |

| B−V color index | +1.26[2] |

| Variable type | L[5] |

| Astrometry | |

| Radial velocity (Rv) | +6.00[6] km/s |

| Proper motion (μ) | RA: −4.97[1] mas/yr Dec.: 1.67[1] mas/yr |

| Parallax (π) | 0.52 ± 0.17 mas[1] |

| Distance | 6.2k ly (1.9k[7] pc) |

| Absolute magnitude (MV) | −9.0[4] |

| Details | |

| Mass | 20[4] M☉ |

| Radius | 485[7] R☉ |

| Luminosity | 212,000 ± 12,300[7] L☉ |

| Surface gravity (log g) | 0.50[8] cgs |

| Temperature | 5,625 ± 312[7] K |

| Metallicity | +0.05[8] |

| Age | 6.8[9] Myr |

| Other designations | |

| Database references | |

| SIMBAD | data |

V382 Carinae, also known as x Carinae (x Car), is a yellow hypergiant in the constellation Carina. It is a G-type star with a mean apparent magnitude of +3.93, and a variable star of low amplitude.

Variability

The radial velocity of V382 Carinae has long been known to be variable, but variations in its brightness were unclear. Brightness variations were detected by some observers, but others found it to be constant.[11] It was formally named as a variable star in 1981, listed in the General Catalogue of Variable Stars as a possible δ Cephei variable.[12][3] It has been described as a pseudo-Cepheid, a supergiant with pulsations similar to a Cepheid but less regular.[8]

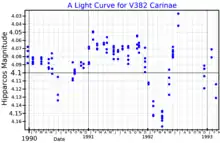

Analysis of Hipparcos photometry showed clear variation with a maximum range of 0.12 magnitudes and the star was treated as an α Cygni variable. A period of 556 days was suggested, but it is not entirely consistent.[13] It is now generally treated as a semiregular or irregular supergiant.[8][5]

Properties

V382 Car is the brightest yellow hypergiant in the night sky, easily visible to the naked eye and brighter than Rho Cassiopeiae although not visible from much of the northern hemisphere. It is 6,200 light years from Earth and around 500 times the radius of the Sun.[7] The large size means that V382 Car is over 200,000 times as luminous as the sun. The low infrared excess suggest that V382 Carinae may be cooling towards a red supergiant phase, less common than yellow hypergiants evolving towards hotter temperatures.[4][14]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 van Leeuwen, Floor (13 August 2007). "Validation of the new Hipparcos reduction". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 474 (2): 653–664. arXiv:0708.1752. Bibcode:2007A&A...474..653V. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20078357. eISSN 1432-0746. ISSN 0004-6361.

- 1 2 3 Ducati, J. R. (2002). "VizieR Online Data Catalog: Catalogue of Stellar Photometry in Johnson's 11-color system". CDS/ADC Collection of Electronic Catalogues. 2237. Bibcode:2002yCat.2237....0D.

- 1 2 Samus, N. N.; Durlevich, O. V.; et al. (2009). "VizieR Online Data Catalog: General Catalogue of Variable Stars (Samus+ 2007-2013)". VizieR On-line Data Catalog: B/GCVS. Originally Published in: 2009yCat....102025S. 1. Bibcode:2009yCat....102025S.

- 1 2 3 4 Achmad, L.; et al. (1992). "A photometric study of the G0-4 Ia(+) hypergiant HD 96918 (V382 Carinae)". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 259: 600–606. Bibcode:1992A&A...259..600A.

- 1 2 Watson, C. L. (2006). "The International Variable Star Index (VSX)". The Society for Astronomical Sciences 25th Annual Symposium on Telescope Science. Held May 23–25. 25: 47. Bibcode:2006SASS...25...47W.

- ↑ Gontcharov, G. A. (2006). "Pulkovo Compilation of Radial Velocities for 35 495 Hipparcos stars in a common system". Astronomy Letters. 32 (11): 759–771. arXiv:1606.08053. Bibcode:2006AstL...32..759G. doi:10.1134/S1063773706110065. S2CID 119231169.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Groenewegen, M. A. T. (2020). "Analysing the spectral energy distributions of Galactic classical Cepheids". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 635: A33. arXiv:2002.02186. Bibcode:2020A&A...635A..33G. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201937060. S2CID 211043995.

- 1 2 3 4 Usenko, I. A.; Kniazev, A. Yu.; Berdnikov, L. N.; Kravtsov, V. V. (2011). "Spectroscopic studies of Cepheids (S Cru, AP Pup, AX Cir, S TrA, T Cru, R Mus, S Mus, U Car) and semiregular bright supergiants (V382 Car, HD 75276, R Pup) in the southern hemisphere". Astronomy Letters. 37 (7): 499. Bibcode:2011AstL...37..499U. doi:10.1134/S1063773711070061. S2CID 122968535.

- ↑ Tetzlaff, N; Neuhäuser, R; Hohle, M. M (2011). "A catalogue of young runaway Hipparcos stars within 3 kpc from the Sun". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 410 (1): 190–200. arXiv:1007.4883. Bibcode:2011MNRAS.410..190T. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2010.17434.x. S2CID 118629873.

- ↑ "Hipparcos Tools Interactive Data Access". Hipparcos. ESA. Retrieved 8 December 2021.

- ↑ Balona, L. A. (1982). "Radial Velocity Observations of Yellow Supergiants". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 201: 105–110. Bibcode:1982MNRAS.201..105B. doi:10.1093/mnras/201.1.105.

- ↑ Kholopov, P. N.; Samus', N. N.; Kukarkina, N. P.; Medvedeva, G. I.; Perova, N. B. (1981). "65th Name-List of Variable Stars". Information Bulletin on Variable Stars. 1921: 1. Bibcode:1981IBVS.1921....1K.

- ↑ Van Leeuwen, F.; Van Genderen, A. M.; Zegelaar, I. (1998). "Hipparcos photometry of 24 variable massive stars (α Cygni variables)". Astronomy and Astrophysics Supplement Series. 128: 117–129. Bibcode:1998A&AS..128..117V. doi:10.1051/aas:1998129.

- ↑ Stothers, R. B.; Chin, C. W. (2001). "Yellow Hypergiants as Dynamically Unstable Post–Red Supergiant Stars". The Astrophysical Journal. 560 (2): 934. Bibcode:2001ApJ...560..934S. doi:10.1086/322438. hdl:2060/20010083764.