| Bahram II 𐭥𐭫𐭧𐭫𐭠𐭭 | |

|---|---|

| King of Kings of Iran and non-Iran[lower-alpha 1] | |

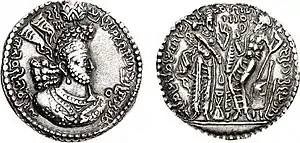

.jpg.webp) Drachma of Bahram II | |

| Shahanshah of the Sasanian Empire | |

| Reign | September 274 – 293 |

| Predecessor | Bahram I |

| Successor | Bahram III |

| Died | 293 |

| Consort | Shapurdukhtak |

| Issue | Bahram III |

| House | House of Sasan |

| Father | Bahram I |

| Religion | Zoroastrianism |

Bahram II (also spelled Wahram II or Warahran II; Middle Persian: 𐭥𐭫𐭧𐭫𐭠𐭭) was the fifth Sasanian King of Kings (shahanshah) of Iran, from 274 to 293. He was the son and successor of Bahram I (r. 271–274). Bahram II, while still in his teens, ascended the throne with the aid of the powerful Zoroastrian priest Kartir, just like his father had done.

He was met with considerable challenges during his reign, facing a rebellion in the east led by his brother, the Kushano-Sasanian dynast Hormizd I Kushanshah, who also assumed the title of King of Kings and possibly laid claims to the Sasanian throne. Another rebellion, led by Bahram II's cousin Hormizd of Sakastan in Sakastan, also occurred around this period. In Khuzestan, a Zoroastrian factional revolt led by a high-priest (mowbed) occurred. The Roman emperor Carus exploited the turbulent situation of Iran by launching a campaign into its holdings in Mesopotamia in 283. Bahram II, who was in the east, was unable to mount an effective coordinated defense at the time, possibly losing his capital of Ctesiphon to the Roman emperor. However, Carus died soon afterwards, reportedly being struck by lightning. As a result, the Roman army withdrew, and Mesopotamia was reclaimed by the Sasanians. By the end of his reign, Bahram II had made peace with the Roman emperor Diocletian and put an end to the disturbances in Khuzestan and the east.

In the Caucasus, Bahram II strengthened Sasanian authority by securing the Iberian throne for Mirian III, an Iranian nobleman from the House of Mihran. Bahram II has been suggested by scholars to be the first Sasanian ruler to have coins minted of his family. He also ordered the carving of several rock reliefs that unambiguously emphasize distinguished representations of his family and members of the high nobility. He was succeeded by his son Bahram III, who after only four months of reign, was overthrown by Narseh, a son of the second Sasanian ruler, Shapur I (r. 240–270).

Name

His theophoric name "Bahram" is the New Persian form of the Middle Persian Warahrān (also spelled Wahrām), which is derived from the Old Iranian Vṛθragna.[1] The Avestan equivalent was Verethragna, the name of the old Iranian god of victory, whilst the Parthian version was *Warθagn.[1] The name is transliterated in Greek as Baranes,[2] whilst the Armenian transliteration is Vahagn/Vrām.[1] The name is attested in Georgian as Baram[3] and Latin as Vararanes.[4]

Background

Bahram II was the eldest son of Bahram I (r. 271–274), the fourth king (shah) of the Sasanian dynasty, and the grandson of the prominent shah Shapur I (r. 240–270).[5] The Sasanians had supplanted the Parthian Arsacid Empire as the sovereigns of Iran in 224, when Ardashir I (Bahram II's great-grandfather) defeated and killed its last monarch Artabanus IV (r. 213–224) at the Battle of Hormozdgan.[6] A terminus post quem for Bahram II's birth is c. 262, since that is the date of Shapur I's inscription at the Ka'ba-ye Zartosht,[7] which mentions the rest of the royal family but not him.[8] His father, Bahram I, although the eldest son of Shapur I, was not considered a candidate for succession, probably due to his mother's lowly origin. She was either a minor queen or perhaps even a concubine.[9][10] Shapur I died in 270, and was succeeded by his son Hormizd I, who only reigned for a year before he died. Bahram I, with the aid of the powerful Zoroastrian priest Kartir, ascended the throne.[11] He then made a settlement with his brother Narseh to give up his entitlement to the throne in return for the governorship of the important frontier province of Armenia, which was constantly the source of conflict between the Roman and Sasanian Empires.[9] Nevertheless, Narseh still most likely viewed Bahram I as a usurper.[11]

Governorship and accession

Bahram was briefly given the governorship of the southeastern provinces of Sakastan, Hind and Turgistan, which Narseh had previously governed.[12][13] Sakastan was far away from the imperial court in Ctesiphon, and ever since its conquest the Sasanians had found it difficult to control.[14] As a result, the province had since its early days functioned as a form of vassal kingdom, ruled by princes from the Sasanian family, who held the title of sakanshah ("King of the Saka").[14] Bahram I's reign lasted briefly, ending in September 274 with his death.[11] Bahram II, still in his teens,[12] succeeded him as shah; he was probably aided by Kartir to ascend the throne instead of Narseh.[5][15] This most likely frustrated Narseh, who held the title of Vazurg Šāh Arminān ("Great King of Armenia"), which was used by the heir to the throne.[16]

Bahram II's accession is mentioned in the narratives included in the history of the medieval Iranian historian al-Tabari;

"He is said to have been knowledgeable about the affairs [of government]. When he was crowned, the great men of state called down blessings on his head, just as they had done for his forefathers, and he returned to them greetings in a handsome manner and behaved in a praiseworthy fashion toward them. He was wont to say: If fortune furthers our designs, we receive this with thankfulness; if the reverse, we are content with our share."

Reign

Wars

Bahram II was met with considerable challenges during his reign. His brother Hormizd I Kushanshah, who governed the eastern portion of the empire (i.e., the Kushano-Sasanian Kingdom), rebelled against him.[18][19] Hormizd I Kushanshah was the first Kushano-Sasanian ruler to mint coins with the inscription of "Hormizd, the Great Kushan King of Kings" instead of the traditional "Great Kushan King" title.[20] The Kushano-Sasanian king, now laying claims to the title of King of Kings, which had originally also been used by the Kushan Empire, displays a "noteworthy transition" (Rezakhani) in Kushano-Sasanian ideology and self-perception and possibly a direct dispute with the ruling branch of the Sasanian family.[20] Hormizd I Kushanshah was supported in his efforts by the Sakastanis, Gilaks, and Kushans.[16] Another revolt also occurred in Sakastan, led by Bahram II's cousin Hormizd of Sakastan, who has been suggested to be the same person as Hormizd I Kushanshah.[18] However, according to the Iranologist Khodadad Rezakhani, this proposal must now be disregarded.[20] At the same time, a revolt led by a high-priest (mowbed) occurred in the province of Khuzestan, which was seized by the latter for a period.[21]

Meanwhile, the Roman emperor Carus, hearing of the civil war occurring in the Sasanian Empire, chose to take advantage of the situation by making a campaign into the empire in 283.[18] He invaded Mesopotamia while Bahram II was in the east, and even besieged the Sasanian capital of Ctesiphon without much fighting.[11][22] The Sasanians, due to severe internal problems, were unable to mount an effective coordinated defense at the time; Carus and his army may have captured Ctesiphon.[23] However, Carus briefly died afterwards, reportedly being struck by lightning.[23] The Roman army as a result withdrew, and Mesopotamia was re-captured by the Sasanians.[11]

Consolidation of the empire

The following year, Bahram II made peace with the new Roman emperor Diocletian, who was faced with internal issues of his own.[11][22] The terms of the peace reportedly divided Armenia between the two empires, with Western Armenia being ruled by the pro-Roman Arsacid prince Tiridates III, and the remaining greater portion being kept by Narseh.[22] However, this division is dismissed by the modern historian Ursula Weber, who argues that it conflicts with other sources, and that the Sasanians most likely kept control over Armenia until the later Peace of Nisibis (299).[9]

In the same year, Bahram II secured the Iberian throne for Mirian III, an Iranian nobleman from the House of Mihran, one of the Seven Great Houses of Iran.[24] His motive was to strengthen Sasanian authority in the Caucasus and utilize the position of the Iberian capital Mtskheta as an entrance to the important passes through the Caucasus Mountains.[24] This was of such importance to Bahram II that he allegedly went in person to Mtskheta in order to secure Mirian III's position.[24] He also sent one of his grandees named Mirvanoz (also a Mihranid) to the country in order to act as the guardian of Mirian III, who was then aged seven.[25] After Mirian III's marriage with Abeshura (daughter of the previous Iberian ruler Aspacures), 40,000 Sasanian "select mounted warriors/cavalry" were subsequently stationed in eastern Iberia, Caucasian Albania and Gugark. In western Iberia, 7,000 Sasanian cavalrymen were sent to Mtskheta to safeguard Mirian III.[26]

By the time of Bahram II's death in 293, the revolts in the east had been suppressed, with his son and heir Bahram III being appointed the governor of Sakastan, receiving the title of sakanshah ("King of the Saka").[11][22] Following Bahram II's death, Bahram III, against his own will, was proclaimed shah in Pars by a group of nobles led by Wahnam and supported by Adurfarrobay, governor of Meshan.[27] After four months of reigning, however, he was overthrown by Narseh, who had Wahnam executed.[9] The line of succession was thus shifted to Narseh, whose descendants continued to rule the empire until its fall in 651.[6]

Relations with Kartir and religious policy

Before Bahram II, the Sasanian shahs had been "lukewarm Zoroastrians."[15] He displayed a particular fondness to his name-deity by giving his son the name of Bahram, and by selecting the wings of the god's bird, Verethragna, as the central component of his crown.[11] Bahram II, like his father, received the influential Zoroastrian priest Kartir well. He saw him as his mentor, and handed out several honors to him, giving him the rank of grandee (wuzurgan), and appointing him as the supreme judge (dadwar) of the whole empire, which implies that thenceforth priests were given the office of judge.[11][28] Kartir was also appointed the steward of the Anahid fire-temple at Istakhr, which had originally been under the care of the Sasanian family.[11][16] The Sasanian kings thus lost much of their religious authority in the empire.[16] The clergy from now on served as judges all over the country, with court cases most likely being based on Zoroastrian jurisprudence, with the exception of when representatives of other religions had conflicts with each other.[16]

It is thus under Bahram II that Kartir unquestionably becomes a powerful figure in the empire; the latter claimed on his inscription at the Ka'ba-ye Zartosht that he "struck down" the non-Zoroastrian minorities, such as the Christians, Jews, Mandaeans, Manichaeans, and Buddhists.[15] According to the modern historian Parvaneh Pourshariati: "it is not clear, however, to what extent Kartir's declarations reflect the actual implementation, or for that matter, success, of the measures he is supposed to have promoted."[29] Indeed, Jewish and Christian sources, for example, make no mention of persecutions during this period.[29][30]

Coins

.jpg.webp)

Starting with Bahram II, all the Sasanian shahs are portrayed with earrings on their coins.[31] He is the first shah to have wings on his crown, which refers to the wings of the god's bird, Verethragna.[32] Like his predecessors (with the exception of Ardashir I and Shapur I, whose legends were slightly different), Bahram II's legend on his coinage was "the Mazda-worshiping, divine Bahram, King of Kings of Iran(ians) and non-Iran(ians), whose image/brilliance is from the gods."[33][34][lower-alpha 2]

Several coin types were minted during Bahram II's reign; one type imitates him alone; another with him and a female figure; a third one with Bahram II and an unbearded youngster wearing a high tiara (known as a Median bonnet); and a fourth one shows Bahram II with the female figure and the unbearded youngster all together.[11][35][36] The female figure is wearing different headdress on some of the coins, sometimes with a boar, griffin, horse or eagle.[37] The precise meaning of these variations is unclear.[37]

As the coins' legends contain no information regarding the status of these characters, it is difficult to analyze them.[36] The unbearded youngster is usually understood as being the crown prince Bahram III,[38][11] while the female figure is usually labelled as Bahram II's queen Shapurdukhtak, who was his cousin.[16][36][37] If the supposition is correct, this would make Bahram II the first (and last) shah to have coins minted of his family.[16] According to the Iranologist Touraj Daryaee, "this is an interesting feature of Bahram II in that he was very much concerned to leave a portrait of his family which incidentally gives us information about the court and the Persian concept of the royal banquet (bazm)."[16] The modern historian Jamsheed Choksy has attempted to establish that the female figure in reality illustrates the goddess Anahita,[lower-alpha 3] whilst the unbearded youngster illustrates Verethragna.[37] The reverse shows the traditional fire altar flanked by two attendants.[11]

Drachma of Bahram II with his queen Shapurdukhtak

Drachma of Bahram II with his queen Shapurdukhtak%252C_struck_at_the_Balkh_mint.jpg.webp) Drachma of Bahram II with his son and heir Bahram III

Drachma of Bahram II with his son and heir Bahram III Drachma of Bahram II with Shapurdukhtak and Bahram III

Drachma of Bahram II with Shapurdukhtak and Bahram III

Rock reliefs

Various rock reliefs were carved under Bahram II; one of them being at Guyom, 27 km northwest of Shiraz, where Bahram is portrayed standing alone.[11] An additional relief at Sar Mashhad, south of Kazerun, portrays Bahram as a hunter: a dead lion reclines at his feet, and he thrusts his sword into a second lion as it attacks him.[11] His queen Shapurdukhtak is holding his right hand in a signal of safeguard, whilst Kartir and another figure, most likely a prince, are watching.[11] The scenery has been the subject of several symbolic and metaphorical meanings, thought it is most likely supposed to portray a simple royal display of braveness during a real-life hunt.[11] An inscription of Kartir is underneath the relief.[11] A third relief at Sarab-e Bahram, close to Nurabad, and 40 km north of Bishapur, portrays Bahram II facing, with Kartir and Papak, the governor of Iberia, to his left, and two other grandees to his right.[11]

A fourth relief, at Bishapur, portrays Bahram mounted on a horse, whilst facing an Iranian grandee who is escorting a group of six men resembling Arabs in their clothing, arriving with horses and dromedaries.[11] Apparently, it depicts the dimplomatic mission from the Himyarite king Shammar Yahri'sh at the beginning of his reign.[41] A fifth relief, at Naqsh-e Rostam, portrays Bahram II standing whilst being surrounded by his family members and attendants; to his left are the sculptures of Shapurdukhtak, a prince, the crown prince Bahram III, Kartir, and Narseh.[11] To his right are the sculptures of Papak, and two other grandees.[11]

A sixth relief, portraying an equestrian combat, was carved directly below the tomb of the Achaemenid King of Kings Darius the Great (r. 522–486 BCE).[11] The relief has two panels. The top panel depicts Bahram II's war against Carus, which he claims as a victory. The lower panel depicts Bahram II's war with Hormizd I Kushanshah.[11][18] A seventh relief, at Tang-e (or Sarab-e) Qandil, depicts a divine investiture scene, with Bahram II receiving a flower from Anahita.[42] Bahram II also erected two rock reliefs in Barm-e Delak: the first depicts Bahram II giving a flower to Shapurdukhtak; the second depicts Bahram II making gesture of piety, whilst being offered a diadem by a courtier.[42]

Rock relief of Bahram II at Guyom

Rock relief of Bahram II at Guyom Rock relief at Sar Mashhad, showing Bahram II slaying two lions

Rock relief at Sar Mashhad, showing Bahram II slaying two lions The Sarab-e Bahram relief of Bahram II surrounded by grandees, Kartir and Papak being on his left

The Sarab-e Bahram relief of Bahram II surrounded by grandees, Kartir and Papak being on his left.JPG.webp) Court scene at Naqsh-e Rostam

Court scene at Naqsh-e Rostam Tang-e (or Sarab-e) Qandil relief depicting a divine investiture scene of Bahram II receiving a flower by the goddess Anahita

Tang-e (or Sarab-e) Qandil relief depicting a divine investiture scene of Bahram II receiving a flower by the goddess Anahita First Barm-e Delak relief of Bahram II giving a flower to Shapurdukhtak

First Barm-e Delak relief of Bahram II giving a flower to Shapurdukhtak Second Barm-e Delak relief of Bahram II making gesture of piety, whilst being offered a diadem by a courtier

Second Barm-e Delak relief of Bahram II making gesture of piety, whilst being offered a diadem by a courtier

Legacy

During the reign of Bahram II, art in Sasanian Iran flourished, notably in the portrayals of the shah and his courtiers.[11] He is the first and only shah to have a woman illustrated on his coins, apart from the 7th-century Sasanian queen Boran (r. 630–630, 631–632).[43] The modern historian Matthew P. Canepa calls Bahram II a relatively weak shah, whose shortscomings allowed Kartir to take over some of the royal privileges.[44] Military wise, however, Bahram II was more successful, putting an end to the disturbances in Khuzestan and the east, and repelling the Romans from Mesopotamia.[45][46] According to Daryaee and Rezakhani, Bahram II's reign "appears to be one of stability and increasing introspection for the Sasanian administration."[47]

Notes

- ↑ Also spelled "King of Kings of Iranians and non-Iranians".

- ↑ In Middle Persian: Mazdēsn bay Warahrān šāhān šāh Ērān ud Anērān kēčihr az yazdān.[33]

- ↑ The worship of Anahita was popular under the Achaemenids and Sasanians,[39] and she enjoyed the status of patron deity of the Sasanian dynasty.[40]

References

- ↑ Wiesehöfer 2018, pp. 193–194.

- ↑ Rapp 2014, p. 203.

- ↑ Martindale, Jones & Morris 1971, p. 945.

- 1 2 Daryaee & Rezakhani 2017, p. 157.

- 1 2 Shahbazi 2005.

- ↑ Rapp 2014, p. 28.

- ↑ Frye 1984, p. 303.

- 1 2 3 4 Weber 2016.

- ↑ Frye 1983, p. 127.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 Shahbazi 1988, pp. 514–522.

- 1 2 Frye 1984, pp. 303–304.

- ↑ Lukonin 1983, pp. 729–730.

- 1 2 Christensen 1993, p. 229.

- 1 2 3 Skjærvø 2011, pp. 608–628.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Daryaee 2014, p. 11.

- ↑ Bosworth 1999, p. 46.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Shahbazi 2004.

- ↑ Rezakhani 2017, pp. 81–82.

- 1 2 3 Rezakhani 2017, p. 81.

- ↑ Daryaee 2014, pp. 11–12.

- 1 2 3 4 Daryaee 2014, p. 12.

- 1 2 Potter 2013, p. 26.

- 1 2 3 Rapp 2014, pp. 243–244.

- ↑ Toumanoff 1969, p. 22.

- ↑ Rapp 2014, p. 247.

- ↑ Klíma 1988, pp. 514–522.

- ↑ Daryaee 2014, p. 76.

- 1 2 Pourshariati 2008, p. 348.

- ↑ Payne 2015, p. 24.

- ↑ Schindel 2013, p. 832.

- ↑ Schindel 2013, p. 829.

- 1 2 Schindel 2013, p. 836.

- ↑ Shayegan 2013, p. 805.

- ↑ Curtis & Stewart 2008, pp. 25–26.

- 1 2 3 Schindel 2013, p. 831.

- 1 2 3 4 Curtis & Stewart 2008, p. 26.

- ↑ Curtis & Stewart 2008, p. 25.

- ↑ Choksy 1989, p. 131.

- ↑ Choksy 1989, p. 119.

- ↑ Overlaet, Bruno (November 2009). "A Himyarite diplomatic mission to the Sasanian court of Bahram II depicted at Bishapur". Arabian Archaeology and Epigraphy. 20 (2): 218–221. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0471.2009.00313.x.

- 1 2 Canepa 2013, p. 864.

- ↑ Brosius 2000.

- ↑ Canepa 2013, p. 862.

- ↑ Daryaee 2018.

- ↑ Kia 2016, p. 235.

- ↑ Daryaee & Rezakhani 2016, p. 29.

Sources

- Bosworth, C. E., ed. (1999). The History of al-Ṭabarī, Volume V: The Sāsānids, the Byzantines, the Lakhmids, and Yemen. SUNY Series in Near Eastern Studies. Albany, New York: State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-4355-2.

- Brosius, Maria (2000). "Women i. In Pre-Islamic Persia". Encyclopædia Iranica, online edition. New York.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Canepa, Matthew P. (2013). "Sasanian Rock Reliefs". In Potts, Daniel T. (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Iran. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0199733309.

- Choksy, Jamsheed K. (1989). "A Sasanian Monarch, his queen, crown prince, and deities: The coinage of Wahram II". American Numismatic Society. 1: 117–135. JSTOR 43580158. (registration required)

- Christensen, Peter (1993). The Decline of Iranshahr: Irrigation and Environments in the History of the Middle East, 500 B.C. to A.D. 1500. Museum Tusculanum Press. pp. 1–351. ISBN 978-1784533182.

- Curtis, Vesta Sarkhosh; Stewart, Sarah (2008). The Sasanian Era. I.B.Tauris. pp. 1–200. ISBN 978-1845116903.

- Daryaee, Touraj (2014). Sasanian Persia: The Rise and Fall of an Empire. I.B.Tauris. pp. 1–240. ISBN 978-0857716668.

- Daryaee, Touraj; Rezakhani, Khodadad (2016). From Oxus to Euphrates: The World of Late Antique Iran. H&S Media. pp. 1–126. ISBN 978-1780835778.

- Daryaee, Touraj; Rezakhani, Khodadad (2017). "The Sasanian Empire". In Daryaee, Touraj (ed.). King of the Seven Climes: A History of the Ancient Iranian World (3000 BCE – 651 CE). UCI Jordan Center for Persian Studies. pp. 1–236. ISBN 978-0692864401.

- Daryaee, Touraj (2018). "Bahram II". In Nicholson, Oliver (ed.). The Oxford Dictionary of Late Antiquity. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-866277-8.

- Lukonin, V. G. (1983). "Political, Social and Administrative Institutions: Taxes and Trade". In Yarshater, Ehsan (ed.). The Cambridge History of Iran, Volume 3(2): The Seleucid, Parthian and Sasanian Periods. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 681–747. ISBN 0-521-24693-8.

- Multiple authors (1988). "Bahrām". Encyclopædia Iranica, online edition, Vol. III, Fasc. 5. New York. pp. 514–522.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Payne, Richard E. (2015). A State of Mixture: Christians, Zoroastrians, and Iranian Political Culture in Late Antiquity. Univ of California Press. pp. 1–320. ISBN 978-0520292451.

- Pourshariati, Parvaneh (2008). Decline and Fall of the Sasanian Empire: The Sasanian-Parthian Confederacy and the Arab Conquest of Iran. I.B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1-84511-645-3.

- Potter, David (2013). Constantine the Emperor. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0199755868.

- Frye, R. N. (1983). "The political history of Iran under the Sasanians". In Yarshater, Ehsan (ed.). The Cambridge History of Iran, Volume 3(1): The Seleucid, Parthian and Sasanian Periods. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-20092-X.

- Frye, R. N. (1984). The History of Ancient Iran. C.H.Beck. ISBN 9783406093975.

- Schindel, Nikolaus (2013). "Sasanian Coinage". In Potts, Daniel T. (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Iran. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0199733309.

- Kia, Mehrdad (2016). The Persian Empire: A Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1610693912. (2 volumes)

- Klíma, O. (1988). "Bahrām III". Encyclopædia Iranica, Vol. III, online edition, Fasc. 5. New York. pp. 514–522.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Martindale, J. R.; Jones, A. H. M.; Morris, J. (1971). The Prosopography of the Later Roman Empire: Volume 1, AD 260-395. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521072335.

- Shahbazi, A. Shapur (1988). "Bahrām II". Encyclopædia Iranica, online edition, Vol. III, Fasc. 5. New York. pp. 514–522.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Shahbazi, A. Shapur (2004). "Hormozd Kusansah". Encyclopædia Iranica, online edition. New York.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Shahbazi, A. Shapur (2005). "Sasanian dynasty". Encyclopædia Iranica, online edition. New York.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Shayegan, M. Rahim (2013). "Sasanian Political Ideology". In Potts, Daniel T. (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Iran. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0199733309.

- Skjærvø, Prods Oktor (2011). "Kartir". Encyclopædia Iranica, online edition, Vol. XV, Fasc. 6. New York. pp. 608–628.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Rapp, Stephen H. (2014). The Sasanian World through Georgian Eyes: Caucasia and the Iranian Commonwealth in Late Antique Georgian Literature. Routledge. ISBN 978-1472425522.

- Rezakhani, Khodadad (2017). ReOrienting the Sasanians: East Iran in Late Antiquity. Edinburgh University Press. pp. 1–256. ISBN 978-1474400299.

- Toumanoff, Cyril (1969). "Chronology of the early kings of Iberia". Traditio. Cambridge University Press. 25: 1–33. doi:10.1017/S0362152900010898. JSTOR 27830864. S2CID 151472930. (registration required)

- Weber, Ursula (2016). "Narseh". Encyclopædia Iranica, online edition. New York.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Wiesehöfer, Josef (2018). "Bahram I". In Nicholson, Oliver (ed.). The Oxford Dictionary of Late Antiquity. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-866277-8.

Further reading

- Gnoli; Jamzadeh, G. P. (1988). "Bahrām (Vərəθraγna)". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. III, Fasc. 5. pp. 510–514.