Vernon March | |

|---|---|

Vernon March, ca. 1925 | |

| Born | 1891 |

| Died | 11 June 1930 Farnborough, Kent, England, United Kingdom |

| Nationality | British |

| Education | No formal training |

| Known for | Sculpture |

| Notable work | "Psyche" The Cenotaph, Cape Town Samuel de Champlain Monument Diamond War Memorial National War Memorial of Canada |

Vernon March (1891–1930) was an English sculptor, renowned for major monuments such as the National War Memorial of Canada in Ottawa, Ontario, the Samuel de Champlain Monument in Orillia, Ontario, and the Cape Town Cenotaph, South Africa. Without the benefit of a formal education in the arts, he was the youngest exhibitor at The Exhibition of the Royal Academy of Arts.

Background

Vernon March, son of George Henry March and his wife Elizabeth Blenkin,[1] was born in 1891 in Kingston upon Hull, in the East Riding of Yorkshire, England.[2] His father was a seed crusher foreman (oil miller) in Yorkshire.[3][4] By 1901, the March family had moved to Battersea, London, England, where his father worked as a builder's clerk.[5] Vernon was the youngest of nine children, eight of whom had careers as artists. Three of the March siblings became sculptors, Sydney, Elsie, and Vernon. The other five siblings who chose a career in the arts were Edward, Percival, Frederick, Dudley, and Walter. Vernon's ninth sibling was his sister Eva Blenkin March. Their parents George and Elizabeth both died in 1904.[6][7]

At the time of the 1911 census, all nine of the March siblings, as yet unmarried, were living together in their 17-roomed home called "Goddendene" in Locksbottom, Farnborough, Kent, England.[8] Two of the siblings eventually married, Eva and Frederick, and produced a total of three children between them. Vernon's sister Eva married Charles Francis Newman in 1916.[9] [10] They had one child, a daughter, Heather.[11] His brother Frederick married a native of Scotland, Agnes Annie Gow, in 1926.[12] They had two children, Elizabeth and Cecil.[13][14] Vernon served with the Royal Flying Corps after enlisting on 8 March 1916.[15] He was discharged less than one year later, on 24 January 1917, with a rank of Air Mechanic 2nd Class.[16]

Career

The March family established studios at the family home of Goddendene in Locksbottom, Farnborough. In 1911, Vernon exhibited two of his works at The Royal Glasgow Institute of the Fine Arts Annual Exhibition. Between 1907 and 1927, he exhibited seven times at The Exhibition of the Royal Academy of Arts, with a total of twelve works.[17] Vernon had the distinction of being the youngest exhibitor at the Royal Academy of Arts, as he was just sixteen when his sculpture of Psyche was exhibited and purchased on the third day of the event in 1907.[18]

Years later, the prodigy was awarded the commission for a war memorial in Cape Town, to honour the fallen of World War I. The Cenotaph memorial has a sandstone base and columns, with bronze plaques and figures. It features winged Victory holding a laurel wreath, and standing on top of a globe, a serpent of evil under her feet. The winged figure on the tall central column is flanked by two South African soldiers on shorter columns. The Cenotaph is located on Heerengracht Street. It now commemorates not only the fallen soldiers of World War I, but also World War II and the Korean War.[19][20] It is the site of the annual Armistice Day wreath-laying ceremony and procession. The Cenotaph was originally unveiled in Adderley Street on 3 August 1924. Street widening in 1959 required that the memorial be moved and reoriented. At that time, additional plaques commemorating the soldiers of World War II and the Korean War were added. The Cenotaph was then unveiled for the second time on 8 November 1959.[20] The Cenotaph was relocated again in 2013, from Adderley Street to Heerengracht Street, to make way for a new MyCiTi bus station.[21][22]

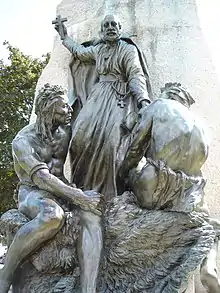

While the Samuel de Champlain Monument in Orillia, Ontario was installed in 1925, a year after the Cape Town memorial, the process began years earlier. Charles Harold Hale was known as "Mr. Orillia" due to his myriad accomplishments on behalf of the city. The idea of a monument to Champlain in the city of Orillia was his brainchild. Hale championed the cause and obtained funding for the project.[23] The competition in 1912 for the design garnered twenty-two entries from three countries, Canada, England, and France. The winning entry was submitted by twenty-year-old Vernon March. The initial target date for completion of the monument was August 1915, to honour the 300th anniversary of Champlain's visit to Huronia. However, World War I delayed the project. The Champlain monument was finally unveiled on 1 July 1925 in Couchiching Park in Orillia, Ontario.[23] On a central pedestal stands a twelve foot tall bronze Champlain in full court attire. Below him on one side there is a robed priest holding a cross above Canadian natives. This side symbolises Christianity. On the side symbolising Commerce, there is a fur trader examining a pelt with two additional natives.[23]

A war memorial dedicated to the citizens of Derry, Northern Ireland who lost their lives in World War I was first considered by public leaders in 1919. After several years of efforts at obtaining the necessary funding, the design and location of the monument were approved by the local war memorial committee in April 1925.[24] Vernon March won the commission to build the memorial that he and his brother Sydney March had designed. The Diamond War Memorial is of bronze and Portland stone. In the center, a winged Victory holds aloft a laurel wreath. The tall column on which she stands has the names of the fallen on four sides. At the base of the monument there are two bronze figures on shorter columns, a soldier on one side who represents the Army and a sailor on the other who represents the Navy. The cenotaph is located on The Diamond in the center of the walled city of Derry. It was unveiled on 23 June 1927.[24]

National War Memorial of Canada

In 1925, Vernon participated in an open, world-wide competition to design and build the National War Memorial of Canada. He was one of seven finalists out of a total of 127 entrants. The seven finalists then submitted scale models of their designs.[19] Vernon was awarded the commission in January 1926 with his entry of "The Great Response of Canada."[25] His design included Liberty holding a torch and winged Victory a laurel wreath, both bronze figures at the top of a granite arch. Below, a cannon is present at the rear of the monument. In front of the cannon, there are twenty-two bronze soldiers under the arch, representing the branches of the Canadian military forces that existed during the First World War.[26]

Work on the monument had not yet been completed when Vernon died of pneumonia in 1930.[19] Six of his siblings completed the bronze statues for the monument. They moulded the figures in clay and cast them in plaster. Then, the bronzes were finished in their foundry at Goddendene. The family completed the work by July 1932. However, construction of the arch in Canada could not commence because the site in Ottawa had not yet been prepared. The bronze memorial groups were mounted on a base instead, and shown at Hyde Park in London. After six months, they were then transferred to the studio in Farnborough where they remained until they were shipped to Canada in 1937.[25]

After a contract was won by Montreal contractors E.G.M. Cape and Company in December 1937, the arch and base for the monument were constructed in Ottawa. Sydney March directed the construction with the assistance of his brothers. The monument, including installation of the bronzes, was finished on 19 October 1938, and landscaping of the area surrounding the memorial commenced. Everything was completed in time for the Royal visit the following spring. The National War Memorial of Canada commemorates the Canadian response during World War I. King George VI performed the unveiling of the monument on 21 May 1939 during a ceremony with an audience of an estimated 100,000.[25]

Victory and Liberty atop the National War Memorial

Victory and Liberty atop the National War Memorial Front

Front Side

Side Rear

Rear

Other collaborative works

One of the first monuments on which the March siblings collaborated was the Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers South African War Memorial; however, Vernon was still a child when it was built and erected.[18] Another project on which the family collaborated was the Lewes War Memorial at School Hill on High Street in Lewes, East Sussex, England. Vernon was the main sculptor for the monument. There is a central obelisk of Portland stone topped by a globe. A bronze winged Victory stands on top of the globe with her arms raised, a laurel wreath in one hand. Two other bronze angels sit near the base of the monument, one on each side. There are adjacent shields, also of bronze, which list the names of the fallen soldiers of World War I.[27] The Lewes War Memorial was unveiled and dedicated on 6 September 1922. It was rededicated on 1 March 1981, to include the deceased soldiers of World War II.[27] On 29 October 1985, the monument was listed as a Grade II structure on the National Heritage List for England.[28] A Grade II structure is deemed to be nationally important and of special interest.[29][28]

The March family also worked together on the war memorial at Sydenham, London, England. Sydney March was the main sculptor for the monument which is now a tribute to the deceased soldiers of both World War I and II who were employees of the Sydenham South Suburban Gas Works. The memorial in front of Livesey Memorial Hall in the London Borough of Lewisham features a bronze figure of Victory standing atop a globe on a wreathed base, with serpents at her feet.[30] Bronze plaques listed the names of fallen soldiers. The plaques also gave the names of those from the company who served in the wars. The Sydenham War Memorial was unveiled by Lord Robert Cecil on 4 June 1920. Also referred to as the Livesey Hall War Memorial, the monument was listed as a Grade II structure on the National Heritage List for England on 30 August 1996.[31] In October 2011, three of the plaques from the front of the monument were stolen.[30]

Death

Vernon March died of pneumonia at age 38 on 11 June 1930 in Farnborough, Kent, England.[32][33] Most of the members of his family, including his parents George and Elizabeth, were interred at Saint Giles the Abbot Churchyard in Farnborough. In 1922, his brother Sydney March had sculpted the bronze angel monument that marked the family grave.[17] Vernon was buried in the family plot on 14 June 1930.[34] His last surviving sibling Elsie March died in 1974.[35]

Legacy

The April 2011 edition of the Chelsfield Village Voice, the monthly newsletter for Chelsfield, Bromley, described a talk that local historian and author Paul Rason had given the previous month to the area historical society. The subject of the lecture was the March family of artists. The talk was accompanied by photographs of the March family home of Goddendene in Locksbottom, Farnborough. The presentation also included images of the bronze statues of the National War Memorial of Canada.[36] In 2011, an exhibition was held at the Bromley Museum at The Priory in Orpington, Bromley. The exhibition featured the work of local artists, and included scale models by members of the March family.[36] A black and white, silent movie filmed in 1924 followed the March artists as they worked in their studios at Goddendene, and has been reproduced by British Pathé.[37]

The original model for the National War Memorial is displayed in the Royal Canadian Legion Hall of Honour in the Canadian War Museum in Ottawa, Ontario, Canada. The National War Memorial of Canada has been the site of Canada's annual National Remembrance Day celebration since 1939, the only exception being those times when construction near the site precluded it.[26] Annual Armistice Day celebrations also take place at Vernon March's Cenotaph war memorial in Cape Town, South Africa and include wreath-laying ceremonies and processions.[20]

The autumn 2010 edition of The Pot, the annual newsletter of the Huronia Chapter of the Ontario Archaeological Society, revealed that the Champlain Monument at Couchiching Park in Orillia had been the site of a ceremony which took place on 16 October 2010. In celebration of the 400th anniversary of the first European visitor to the area, a chapter member played Étienne Brûlé. Events included a flag ceremony, an interview skit, and musical performances. The day's events were a precursor to more elaborate festivities scheduled for 2015, to celebrate the 400th anniversary of Champlain's first visit to Orillia.[38]

Vernon March's Diamond War Memorial in Derry, Northern Ireland has been the inspiration for the Diamond War Memorial Project. The project began in 2007, one of the primary goals being to research the lives of those inscribed on the memorial and disseminate the information. In the process, hundreds of additional names, never inscribed on the memorial, have been uncovered.[39] Miniatures of the Diamond War Memorial are displayed at Saint Columb's Cathedral.[19]

References

- ↑ March, George Henry. "England & Wales, FreeBMD Marriage Index: 1837–1915". ancestry.com. England and Wales Civil Registration Indexes. General Register Office (as re-printed on Ancestry.com).

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|url=(help) - ↑ March, Vernon. "England & Wales, FreeBMD Birth Index, 1837–1915". ancestry.com. England and Wales Civil Registration Indexes. General Register Office (as re-printed on Ancestry.com).

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|url=(help) - ↑ March, George H. "1881 England Census". ancestry.com. Census Returns of England and Wales, 1881. The National Archives of the UK (as re-printed on Ancestry.com).

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|url=(help) - ↑ March, Vernon. "1891 England Census". ancestry.com. Census Returns of England and Wales, 1891. The National Archives of the UK (as re-printed on Ancestry.com).

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|url=(help) - ↑ March, Vernor [sic]. "1901 England Census". ancestry.com. Census Returns of England and Wales, 1901. The National Archives, 1901 (as re-printed on Ancestry.com).

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|url=(help) - ↑ March, George Henry. "England & Wales, FreeBMD Death Index: 1837–1915". ancestry.com. England and Wales Civil Registration Indexes. General Register Office (as re-printed on Ancestry.com).

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|url=(help) - ↑ March, Elizabeth. "England & Wales, FreeBMD Death Index: 1837–1915". ancestry.com. England and Wales Civil Registration Indexes. General Register Office (as re-printed on Ancestry.com).

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|url=(help) - ↑ March, Vernon. "1911 England Census". ancestry.com. Census Returns of England and Wales, 1911. The National Archives of the UK, 1911 (as re-printed on Ancestry.com).

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|url=(help) - ↑ March, Eva B. "England & Wales, Marriage Index: 1916–2005". ancestry.com. England and Wales Civil Registration Indexes. General Register Office (as re-printed on Ancestry.com).

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|url=(help) - ↑ Newman, Charles F. "England & Wales, Marriage Index: 1916–2005". ancestry.com. England and Wales Civil Registration Indexes. General Register Office (as re-printed on Ancestry.com).

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|url=(help) - ↑ Newman, Heather. "England & Wales, Birth Index: 1916–2005". ancestry.com. England and Wales Civil Registration Indexes. General Register Office (as re-printed on Ancestry.com).

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|url=(help) - ↑ March, Frederic H. "England & Wales, Marriage Index: 1916–2005". ancestry.com. England and Wales Civil Registration Indexes. General Register Office (as re-printed on Ancestry.com).

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|url=(help) - ↑ March, Elizabeth E. "England & Wales, Birth Index: 1916–2005". ancestry.com. England and Wales Civil Registration Indexes. General Register Office (as re-printed on Ancestry.com).

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|url=(help) - ↑ March, Cecil G. "England & Wales, Birth Index: 1916–2005". ancestry.com. England and Wales Civil Registration Indexes. General Register Office (as re-printed on Ancestry.com).

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|url=(help) - ↑ March, Vernon. "British Army WWI Pension Records 1914–1920". ancestry.com. War Office: Soldiers' Documents from Pension Claims, First World War. The National Archives of the UK (as re-printed on Ancestry.com).

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|url=(help) - ↑ March, Vernon. "British Army WWI Medal Rolls Index Cards, 1914–1920". ancestry.com. WWI Medal Index Cards. Army Medal Office (as re-printed on Ancestry.com).

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|url=(help) - 1 2 March, Vernon. "Mapping the Practice and Profession of Sculpture in Britain & Ireland 1851–1951". sculpture.gla.ac.uk. University of Glasgow History of Art and HATII. Retrieved 27 March 2012.

- 1 2 "Nine Artists in One Family". The Sydney Mail. 17 February 1909. p. 23. Retrieved 27 March 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 Eamonn Baker (15 July 2008). "Memorial to a celebrated sculptor". Derry Journal. Johnston Publishing Ltd. Retrieved 27 March 2012.

- 1 2 3 The Cenotaph War Memorial, Adderley Street. "flickr". flickr.com. Yahoo! Inc. Retrieved 27 March 2012.

- ↑ "Heritage Statement" (PDF). capetown.gov.za. GIBB Engineering and Science. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 12 April 2012.

- ↑ "Cenotaph war memorial restored in time for Remembrance Day". City of Cape Town. 28 October 2013. Archived from the original on 8 August 2014. Retrieved 2 August 2014.

- 1 2 3 Randy Richmond (22 August 1996). Orillia Spirit: An Illustrated History of Orillia. Dundurn Press Ltd. pp. 64–65. ISBN 9781770700772. Retrieved 27 March 2012.

- 1 2 "Memorial History". diamondwarmemorial.com. Diamond War Memorial Project. Retrieved 27 March 2012.

- 1 2 3 "The Response". veterans.gc.ca. Veterans Affairs Canada. Retrieved 27 March 2012.

- 1 2 "Our Military Heritage – The National War Memorial". legion.ca. The Royal Canadian Legion. Archived from the original on 4 September 2007. Retrieved 29 March 2012.

- 1 2 War Memorial. "Public Sculptures of Sussex – Object Details". publicsculpturesofsussex.co.uk. Cultural Informatics Research Group, University of Brighton. Archived from the original on 13 April 2014. Retrieved 28 March 2012.

- 1 2 Historic England. "War Memorial (1191738)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 28 March 2012.

- ↑ "Listed Buildings". english-heritage.org.uk. English Heritage. Archived from the original on 5 January 2013. Retrieved 28 March 2012.

- 1 2 Sydenham, South Suburban Gas Works WW1 and WW2 War Memorial. "Lewisham War Memorials". lewishamwarmemorials.wikidot.com. Local History and Archives Centre, Lewisham. Retrieved 28 March 2012.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ↑ Historic England. "Livesey Hall War Memorial (1253111)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 28 March 2012.

- ↑ March, Vernon. "England & Wales, Death Index: 1916–2005". ancestry.com. England and Wales Civil Registration Indexes. General Register Office (as re-printed on Ancestry.com).

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|url=(help) - ↑ March, Vernon. "England & Wales, National Probate Calendar (Index of Wills and Administrations), 1861–1941". ancestry.com. Calendar of the Grants of Probate and Letters of Administration made in the Probate Registries of the High Court of Justice in England. Principal Probate Registry (as re-printed on Ancestry.com).

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|url=(help) - ↑ "Burial and Cremation Records". farnborough-kent-parish.org.uk. St. Giles the Abbot, Farnborough (Kent). Retrieved 28 March 2012.

- ↑ March, Elsie. "England & Wales, Death Index: 1916–2005". ancestry.com. England and Wales Civil Registration Indexes. General Register Office (as re-printed on Ancestry.com).

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|url=(help) - 1 2 "Local History Group" (PDF). chelsfieldevents.co.uk. Chelsfield Village Voice. April 2011. pp. 3–4. Retrieved 27 March 2012.

- ↑ "Sister and Seven Brothers". britishpathe.com. British Pathé. 1924. Retrieved 28 March 2012.

- ↑ Brulé at Orillia (Autumn 2010). "The Pot" (PDF). huronia.ontarioarchaeology.on.ca. Huronia Chapter of the Ontario Archaeological Society. pp. 1–2. Retrieved 28 March 2012.

- ↑ "About the Project". diamondwarmemorial.com. Diamond War Memorial Project. Retrieved 28 March 2012.

External links

- erika takacs sculpture – Samuel de Champlain Monument in Orillia Photographs of Champlain Monument

- Sydenham, South Suburban Gas Works WW1 and WW2 War Memorial Photograph of Livesey Hall War Memorial

- Vernon March at Find a Grave

- SilverTiger – Lewes War Memorial Photograph of angel representing Liberty

- British Pathé – Sister and Seven Brothers, 1924 Movie of the March siblings