Village des Bories is an open-air museum of 20 or so dry stone huts located 1.5 km west of the Provençal village of Gordes, in the Vaucluse department of France. The area was once an outlying district of the village, under the official name of 'Les Savournins', while the grouping of huts were called 'Les Cabanes' in local parlance.

Location

These huts, which were once agricultural outhouses used on a seasonal basis, stand on a hill at an average altitude of 270–275 metres, between the Sénancole stream – its border to the West – and the Gamache vale – its border to the East, in what the Gordes villagers call the “garrigue” (scrubland) or “montagne” (the hills).

Designations

In the 1809 land map, the hamlet is referred to as “hameau des Savournins”, a designation which is abridged to “Les Savournins” in the 1956 land map. In local parlance, it was still called “Les cabanes” (the huts) in the late 1970s.[1] Its modern, museological name was coined by Pierre Viala, the site’s discoverer, owner and restorer at the time.[2]

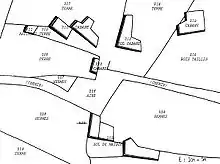

The word “Borie” originates from an 18th-century place name – “Les Borrys”, in the Bouches-du-Rhône département – that was mistakenly construed as meaning “dry stone hut” by a mid 19th-century scholar.[3] In the 1809 land register, the dry stone huts are referred to as “cabane” (when intact and still in use) and “sol de cabane” (when deserted and derelict) (see picture representing “Les Savournins Bas“ in the Napoleonic land register).

History

The emergence of the outlying hamlet of “Les Savournins” dates back to a wide scale campaign of land clearing and cultivation that took place in 18th-century Provence, following a 1766 royal edict. The rush to the hills resulted in masses of stones being extracted from the ground to make way for new fields complete with dry stone walls and huts.[4]

The potsherds found in the huts and fields during the restoration work of the 1970s are characteristic of the earthenware manufactured in the Apt, Vaucluse, region in the 18th-19th centuries.[5]

Building material

The huts were built using locally extracted, 10 to 15 cm-thick, limestone slabs, going by the name of “lauses” or “clapes”.[6]

Structure and form

Out of the 28 stone buildings still extant on the site,

- 20 belong to the so-called “Gordoise nave”, i.e. a rectangular or trapezoid edifice in the form of an upturned keel, either free standing or abutting on another edifice,

- 3 have a rectangular or square plan, with a corbelled vault in the form of a cupola or a half dome,

- 2 have a semi-circular vault of voussoirs as well as a cupola-shaped vault of voussoirs (the two oven houses with their ovens),

- 2 have a circular or horse-shoe-shaped plan (ruined buildings),

- 1 is a conventional first-floor house under a one-sided roof of canal tiles.[7]

The prevalence of the “Gordoise nave”, together with the use of mortarless masonry, lends the hamlet a certain architectural unity.[8] .

The “Gordoise Nave”

Functionally, the “Gordoise nave” appears to have been a multi-purpose edifice used as seasonal dwelling, barn, grain store house, byre, sheep shelter, silkworm house, tool shed, treading house with vat.

The buildings’ layout and functions

The “Village des Bories” comprises several “groups” of “cabanes” which are distributed across the areas North and South of a lane that runs through the site.[9] A “group” is to be seen as a reunion of two or more edifices, either abutting against, or adjoining, one another, or in proximity, usually round a small yard. It would be wrong, however, to think that each group belonged to a single family. A study of the Napoleonic and modern land registers has shown that some groups did belong to two separate owners or that the same person could own one building in a group and another building in another group.[10]

The site also contains two threshing yards but no wells or water storage tanks (the nearest well, 100 metres away from the centre of the grouping, is dry).[11]

Witnesses to Provençal agricultural history

Based on an analysis of the buildings’ functions, the evidence provided by both land registers, the testimonies of Gordes villagers, and vestigial tree stumps, cereals (wheat, rye) were grown in the area in the 19th century, along with olive, almond and mulberry trees (the latter for silkworm rearing) and vines. There was also a cottage industry of leather sole making.[12]

Also, some stone huts may have belonged to people living in a nearby village other than Gordes, a pattern that was not uncommon in the Provence of old.[13]

The site was listed as a historic monument in 1977[14] and has been open to visitors for a fee ever since. Its current owner and manager is the Gordes municipality.[15]

Gallery

Western sub-grouping in Pierre Viala’s group No 2

Western sub-grouping in Pierre Viala’s group No 2 Group No 5 (as per Viala)

Group No 5 (as per Viala) Group No 3 (as per Viala) (from right to left: dwelling, sheep shelter, barn-cum-granary)

Group No 3 (as per Viala) (from right to left: dwelling, sheep shelter, barn-cum-granary) Entrance of the store room of Group No 4 (as per Viala)

Entrance of the store room of Group No 4 (as per Viala) Inside of the dwelling (now occupied by exhibits) of Group No 4 (as per Viala)

Inside of the dwelling (now occupied by exhibits) of Group No 4 (as per Viala) Some of the exhibits: light swing-ploughs (or ards) and a harrow

Some of the exhibits: light swing-ploughs (or ards) and a harrow

Bibliography

- Pierre Viala, Le village des bories à Gordes dans le Vaucluse, Ed. Le village des bories, Gordes, 1976.

- Christian Lassure, Problèmes d'identification et de datation d'un hameau en pierre sèche : le "village des bories" à Gordes (Vaucluse). Premiers résultats d'enquête, in L'architecture rurale', t. 3, 1979.

- Christian Lassure, « Les Cabanes » à Gordes (Vaucluse) : architecture et édification, in L'architecture vernaculaire rurale, supplément No 2, 1980.

See also

References

- ↑ Just like a number of other localities rife with dry stone huts in neighbouring communities: “Cabanes de Saumane”, “Cabanes de Cabrières”, “Cabanes de Bonnieux”.

- ↑ Pierre Viala, Histoire d'une restauration : le village des bories de Gordes (Vaucluse), in L'architecture rurale en pierre sèche, t. 1, 1977, pp. 151-153.

- ↑ Christian Lassure, La terminologie provençale des édifices en pierre sèche : mythes savants et réalités populaires, in L'architecture rurale, t. 3, 1979, pp. 33-45.

- ↑ On the rush to Provençal hills in the 17th and 18th centuries, see Roget Livet, L'habitat rural et les structures agraires en Basse-Provence, thèse de Lettres, Paris, 1962, Aix-en-Provence, éd. Ophrys, 1962. The author delves into the case of the region of Saint-Saturnin-lès-Apt, a community to the West of Gordes.

- ↑ Pierre Viala, Le village des bories à Gordes dans le Vaucluse, Ed. Le village des bories, Gordes, 1976, 16 p., p. 4.

- ↑ Christian Lassure, « Les Cabanes » à Gordes (Vaucluse) : architecture et édification, in L'architecture vernaculaire rurale, suppl. No 2, 1980, pp. 143-160, « Le matériau: nature, origine et façonnage », p. 146.

- ↑ Christian Lassure, « Les Cabanes » à Gordes (Vaucluse)..., op. cit.,. « Classification selon la structure et la morphologie », pp. 146-151.

- ↑ Christian Lassure, « Les Cabanes » à Gordes (Vaucluse)..., 'op. cit., pp. 146-151.

- ↑ Pierre Viala, « Le village des bories... », op. cit., plan p. 3.

- ↑ Christian Lassure, « Les Cabanes » à Gordes (Vaucluse)..., op. cit., note 6, pp. 158-159.

- ↑ Pierre Viala, « Le village des bories... », op. cit., p. 4.

- ↑ Pierre Viala, « Le village des bories... », op. cit., p. 10.

- ↑ Considering that harvesting and threshing in the early 20th century required 12 days’ work, being the owner of a “cabanon” (small hut), “grangeon” (small barn) or “bastidon” (small building) in an outlying plot of land, was no small advantage for a “forain” (outsider). See Daniel Thiery, Pierre sèche et milieu rural dans les montagnes de l'arrière-pays de Grasse (Alpes-Maritimes), in L'architecture vernaculaire, t. 23, 1999, pp. 59-72. Also a page on outsider-owned huts in a village in the Alpes-Maritimes département.

- ↑ Base Mérimée: PA00082045, Ministère français de la Culture. (in French) Village de Bories

- ↑ Official site of Gordes Archived 2010-09-24 at the Wayback Machine. The site claims that the “Village des Bories” has been “inhabited continuously for something like 3000 years, with the bories dating as far back as the Bronze age” although the claim is not borne out by historical and archaeological research.