.jpg.webp)

Montreal was established in 1642 in what is now the province of Quebec, Canada. At the time of European contact the area was inhabited by the St. Lawrence Iroquoians, a discrete and distinct group of Iroquoian-speaking indigenous people. They spoke Laurentian. Jacques Cartier became the first European to reach the area now known as Montreal in 1535 when he entered the village of Hochelaga on the Island of Montreal while in search of a passage to Asia during the Age of Exploration. Seventy years later, Samuel de Champlain unsuccessfully tried to create a fur trading post but the Mohawk of the Iroquois defended what they had been using as their hunting grounds.

A fortress named Ville Marie was built in 1642 as part of a project to create a French colonial empire. Ville Marie became a centre for the fur trade and French expansion into New France until 1760, when it was surrendered to the British army, following the Montreal Campaign. British immigration expanded the city. The city's golden era of fur trading began with the advent of the locally owned North West Company.

Montreal officially became a city in 1832. The city's growth was spurred by the opening of the Lachine Canal and Montreal was the capital of the United Province of Canada from 1844 to 1849. Growth continued and by 1860 Montreal was the largest city in British North America and the undisputed economic and cultural centre of Canada. Annexation of neighbouring towns between 1883 and 1918 changed Montreal back to a mostly Francophone city. The Great Depression in Canada brought unemployment to the city, but this waned in the mid-1930s, and skyscrapers began to be built.

World War II brought protests against conscription and caused the Conscription Crisis of 1944. Montreal's population surpassed one million in the early 1950s. A new metro system was added, Montreal's harbour was expanded, and the St. Lawrence Seaway was opened during this time. More skyscrapers were built along with museums. Montreal's international status was cemented by Expo 67 and the 1976 Summer Olympics. A major league baseball team, the Expos, played in Montreal from 1969 to 2004 when the team relocated to Washington, DC. Historically, business and finance in Montreal were under the control of Anglophones. With the rise of Quebec nationalism in the 1970s, many institutions relocated their headquarters to Toronto.[1]

Pre-contact

The area known today as Montreal had been inhabited by indigenous peoples for some 8,000 years, while the oldest known artifact found in Montreal proper is about 4,000 years old.[2] By about 1000 A.D., nomadic Iroquoian and other peoples around the Great Lakes began to adopt the cultivation of maize and more settled lifestyles. Some settled along the fertile St. Lawrence River, where fishing and hunting in nearby forests supported a full diet. By the 14th century, the people had built fortified villages similar to those described by Cartier on his later visit.[3]

Historians and anthropologists have had many theories about the people encountered by Cartier, as well as the reasons for their disappearance from the valley about 1580. Since the 1950s, archaeological and linguistic comparative studies have established many facts about the people. They are now called the St. Lawrence Iroquoians and recognized by scholars as distinct from other Iroquoian-language people, such as the Huron or Iroquois of the Haudenosaunee, although sharing some cultural characteristics. Their language has been called Laurentian, a distinct branch of the family.[3]

Montreal during the French colonial period

The first European to reach the area was Jacques Cartier on October 2, 1535. Cartier visited the villages of Hochelaga (on Montreal Island) and Stadacona (near modern Quebec City), and noted others in the valley which he did not name. He recorded about 200 words of the people's language.

Seventy years after Cartier, explorer Samuel de Champlain travelled to Hochelaga, but the village no longer existed, nor was there sign of any human habitation in the valley. At times historians theorized that the people migrated west to the Great Lakes (or were pushed out by conflict with other tribes, including the Huron), or suffered infectious disease. Since the 1950s, other theories have been proposed. The Mohawk had most to gain by moving up from New York into the Tadoussac area, at the confluence of the Saguenay and St. Lawrence rivers, which was controlled by local Montagnais.

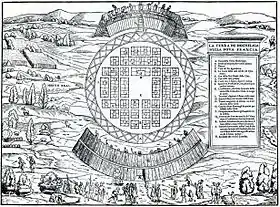

Champlain decided to establish a fur trading post at Place Royal on the Island of Montreal, but the Mohawk, based mostly in present-day New York, successfully defended what had by then become their hunting grounds and paths for their war parties. It was not until 1639 that the French created a permanent settlement on the Island of Montreal, started by tax collector Jérôme le Royer de la Dauversière. Under the authority of the Roman Catholic Société Notre-Dame de Montréal, missionaries Paul Chomedey de Maisonneuve, Jeanne Mance and a few French colonists set up a mission named Ville Marie on May 17, 1642, as part of a project to create a colony dedicated to the Virgin Mary. In 1644, Jeanne Mance founded the Hôtel-Dieu, the first hospital in North America north of Mexico.[4]

Paul Chomedey de Maisonneuve was governor of the colony and on January 4, 1648, he granted Pierre Gadois (who was in his fifties) the first concession of land - some 40 acres (160,000 m2). In 1650, Grou family, the lineage of historian Lionel Groulx, arrived from Rouen, France, and established a land holding known as Coulée Grou which is today encompassed by the borough Rivière-des-Prairies–Pointe-aux-Trembles. In November 1653, another 140 Frenchmen arrived to enlarge the settlement.

By 1651, Ville-Marie had been reduced to less than 50 inhabitants by repeated attacks by the Mohawk. Maisonneuve returned to France that year to recruit 100 men to bolster the failing colony. He had already decided that should he fail to recruit these settlers, he would abandon Ville-Marie and move everyone back downriver to Quebec City. (Even 10 years after its founding, the people of Quebec City still thought of Montreal as "une folle entreprise" - a crazy undertaking.)[5] These recruits arrived on 16 November 1653 and essentially guaranteed the evolution of Ville Marie and of all New France.[5] In 1653 Marguerite Bourgeoys arrived to serve as a teacher. She founded Montreal's first school that year, as well as the Congrégation de Notre-Dame, which became mostly a teaching order. In 1663, the Sulpician seminary became the new Seigneur of the island.

The first water well was dug in 1658 by settler Jacques Archambault, on the orders of Maisonneuve.

Ville Marie would become a centre for the fur trade and the town was fortified in 1725. The French and Iroquois Wars threatened the survival of Ville-Marie until a peace treaty (see the Great Peace of Montreal[6]) was signed at Montreal in 1701. With the Great Peace, Montreal and the surrounding seigneuries (Terrebonne, Lachenaie, Boucherville, Lachine, Longueuil, ...) could develop without the fear of Iroquois raids.[7]

Though Quebec was the capital and thus the centre of government activity, Montreal also served a key administrative function in New France. Along with Quebec and Trois-Rivières, Montreal was considered a district of the colony.[8] Before the cour de la jurisdiction royale was established in 1693, the seminary of St Sulpice had administered justice.[9] Montreal also had a local governor who represented the governor general and a commissaire de la marine who acted as the intendant's representative.[10] While most government positions were appointed, Montreal and the other districts did have some element of democracy, if only briefly. Syndics were elected representatives who attended meetings of the council of Quebec and the Sovereign Council. However, the syndics had little authority and could only raise the concerns of their district's residents. This office existed from 1647 until it was eliminated in the 1670s due to government fears over the potential formation of political factions; in lieu of syndics, citizens brought their issues to the commissaire de la marine.[11] Because of their importance to Montreal and New France, merchants were allowed to establish chambers of commerce called bourses and meet regularly to discuss their concerns.[11] A bourse would have collectively chosen a representative to address these issues with the governor and commissaire de la marine.[12]

Population of Montreal

The Population of the Island of the Montreal during French rule consisted of both native peoples and the French. When the first census was conducted in the colony in 1666, the French population was 659 with an estimated native population of 1000.[13] According to the sources, this was the only point when the native population was higher than the French population on the Island of Montreal. By 1716, the French population had grown to 4,409 people while the native population was 1,177.[14] The French Population of Montreal began slowly through migration. In 1642 a party of 50 Frenchmen representing the Societe de Notre Dame de Montreal pour la conversion des Sauvages de la Nouvelle France set foot on the island that the Compagnie des Cent Associes donated.[15] The initial settlement had 150 individuals in the first ten years; few remained for long because the site of Montreal was vulnerable to Iroquois attacks. Migration to Montreal increased thereafter; between 1653 and 1659, 200 persons arrived.[15] Eventually approximately 1200 to 1500 migrants settled on the island of Montreal between 1642 and 1714; 75% remained and half of them came before 1670.[15] Migrants came from different regions of France: 65 percent of the migrants were rural; 25 percent of the migrants were from the largest cities of France; 10 percent from smaller urban communities.[16]

These migrants came from different groups the largest of which were indentured servants, they were half of the males, excluding those still in service that potentially could go home.[15] By 1681, indentured labour had seen its heyday in both the colony and in Montreal, only religious communities and the richest supported engages who performed agricultural labour.[17] Another prominent group of French migrants was soldiers who accounted for a fifth of all migrants.[18] Soldiers who came in the early part of the colony's history became the notable residents of Ville-Marie, and eventually Montreal.[19] Migrants from a miscellaneous background, who paid their own way to the colony, were an additional fifth of the migrants to Montreal.[15] Women also came to the colony, ¾ of all women were single, and looking for a husband, these were truly permanent residents since single women and whole families did not intend to return to France.[20] The thirty-one girls who arrived in Montreal with the 1653 and 1659 married within the year, some within weeks of landing.[21] Between 1646 and 1717, 178 French girls were married on the Island of Montreal, 20 percent of the overall permanent settlers.[21] During this period the merchant population was relatively small, a hundred came. This was because Quebec City was the primary place for merchants to migrate to; all the merchants who came to Montreal were related to a resident or another merchant.[22]

During the 17th century there were drastic changes in the demographics of Montreal. In 1666, 56 percent of the population were newcomers to Montreal; by 1681, 66% of Montreal was native-born.[23] There was a male to female sex ratio of 163:100 in 1666, by 1681 it was 133:100.[23] Although, the population of Montreal was still dominated by males, the female population grew. The rural proportion represented two-thirds in the first 40 years. However, by 1715-1730 the urban proportion was about 45 percent.[24] Data from 1681 to 1739 show that the point of equilibrium was reached around 1695, with males accounting for 51.6 percent of the population. This percent of the population was maintained until 1710, through migration that was predominantly male.[23] The infant mortality rates in Montreal grew from 9.8% in 1676 to 18.0% to 1706–1715.[25] Illegitimacy rate for Montreal was 1.87 percent higher than the rest of colony due to the status of the Montreal as a garrison town; some unwed mothers from the countryside would abandon their children in the town.[26] Despite some differences in the pattern of population in comparison to the rest of the colony, Montreal's population developed at approximately the same rhythm as that of the whole colony. In the 18th century, the population grew at an even rate of 2.5 percent per annum until 1725 when the growth rate decreased to 0.7 percent per annum.[27]

Economy of Montreal

In the 17th century, Montreal acted as a point of trans-shipment and a stopover on the passage to the interior.[28] Due to the rapids upriver from Montreal, free sailing through the Saint-Laurence ended in Montreal. Portages inland were then taken. This effectively made Montreal a major distribution centre rather than a mere trading post.[28] Pelts and merchandise were stocked for distribution inland and out. Montreal lacked moorings in the 17th century, forcing trans-Atlantic vessels with larger capacity to unload at Quebec. Goods from Quebec had to be transported by river between the two towns until the construction of a road in 1735.[28] Montreal remained subservient to Quebec due to its isolation. Trade between Montreal and France remained indirect.

Not long after its establishment, Montreal provided for its own subsistence.[29] However, the colony was still dependent on France for a range of finished products, iron, and salt.[29] Montreal's principal import, before the end of the 17th century, was finished fabric. The seigneurs of Montreal who owned large flock organized the manufacture and sale of their wool to compensate for the imports. To the contrary, in the early 18th century, for peasants who kept their own sheep and grew flax, production was limited to their own needs. This led to few weavers and a left no more than 5% of textiles sold in Montreal to be manufactured locally. Louise Dechene states: "There was no market-oriented production of fabrics and, understandably no import of raw materials."[29]

Guns, shot, bullets, and powder represented 15% of imported cargo.[30] The presence of guns meant that colonies retained the services of blacksmiths, or arquebusiers, to repair guns, manufacture bullets, and perform other duties to relieve dependence on imports.[31] 4-5% of imports were kettles.[31] The kettle at this time took the form of an "easily transportable large copper cauldron".[31] Knives, scissors, and awls had to be imported. Local production of these items did not begin until approximately 1660. By 1720, all iron tools could be purchased exclusively from colonial blacksmiths.[31] Small stocks of glassware, porcelain, and china were imported as well.

Soon after the founding of the Montreal, when the population numbered 8, the Company of One Hundred Associates gave the city's trading rights up to the colonial merchants. The colonial merchants at Montreal formed the "Communaute des Habitants".[32] Both Indians and Coureurs de Bois supplied furs.[33] The company remained profitable until the Iroquois Wars, where it slipped into semi-bankruptcy. In 1664, The Communaute des Habitants" at Montreal was taken over by the French West India Company.[33] The "compagnie de la colonie" (as the French West India Company were referred to) had significant scale of operations and capital.[34] While the Iroquois Wars did limit trade for a time the Natives were still a lot of trade to be had with them. For example, the Island of Montreal did not have a large native population, but 80,000 natives lived within an 800-kilometre radius of Montreal.[35]

.jpg.webp)

These natives would come to Montreal on occasion to participate in economic activity. One of these occasions happened every August, as Montreal welcomed hundreds of member of various nations to an annual fur fair which dwindled after 1680; as many as 500 to 1000 natives would attend to get better prices than the voyageurs would offer, and the governor would meet them for a ceremony. They would stay outside of town until late September.[36] There were also some natives who lived on the island and in the settlement of Montreal as permanent residents. There were a couple missions founded in Montreal for natives, such as the 1671 La Montagne Mission by the Sulpicians and the Jesuit at Sault-Saint-Louis (Kahnawake).[37] The mission population rose in the 18th century through natural increase and some newcomers; between 1735 and 1752, Kahnawake contained about 1000 people, as did Lac-des-deux-Montagnes. Montreal had some natives residing within the settlement, even if it was temporary, the Jesuits recorded 76 baptisms in 1643 of native children, and this continued to be recorded until 1653.[38] Despite the presence of natives in the settlement of Montreal there seems to be very little intermixing with only seven registered mixed marriages in Montreal, though the number of actually mixed marriages was probably slightly higher.[39] Native slaves were also a reality in Montreal, there were about 50 or so slaves recorded on the island of Montreal in 1716.[39] Therefore, the presence of Natives was definitely necessary for trade, but the Natives were never really integrated into the city of Montreal itself.

Very little information exists on how the colony of Montreal obtained foodstuffs before 1663.[40] The town of Montreal was too small to act as an important internal market. Though habitants came to Montreal to sell their goods (such as eggs, chickens, vegetables, and other goods), it was never a regional distribution centre for grain.[41] Furthermore, despite a surplus of unsold wheat at the colony, flour and lard were still regularly imported to feed French troops during the seventeenth century.[41] The ineffective use of the wheat surplus remained a contentious issue for the habitants in Montreal and the royalty in France.[42] An intendant explained that: "The habitants do not grow hemp because they get nothing for it. Wool is plentiful, but there is no market. They have enough to ensure their subsistence, but since they are all in the same position, the cannot make any money, and this prevents them from meeting other needs and keeps them so poor in winter that we have been told that there are men and women who wander about practically naked."[43]

In the eighteenth century, Montreal was central to the illegal trade of furs.[44] The illegal fur trade can be defined as the "export of furs to any destination other than France".[45] French merchants carried furs were carried down the Richelieu River to English, Dutch, and the converted Jesuit Iroquois at Albany. The contraband was buried outside the walls of Montreal at the request of merchants in order to avoid more loyal French eyes.[46] Furs were traded illegally between Quebec and Albany, however these instances were less extensive than the illegal trade between Quebec and France or Boston.[47] Some estimates place the furs being illegally traded from Montreal to roughly half or two-thirds of total fur-production at the beginning of the 1700s.[48] Later in the century, records appear to be silent. The presence of English supplies amongst the Iroquois during the period, among other reasons, is given as proof of a continued existence of the illegal fur trade between colonies.[48]

The design of Montreal

The organization and building of towns in New France attempted to continue the history of France and had similar designs to the homes and buildings of France. Originally with the lack of stone and the plentiful number of lumber cites like Montreal were almost completely made with wooden buildings designed in the French style.[49] These buildings completely relied on the use of classic French building techniques and many of the craftsmen refused to use anything other than sawn and squared lumber. This caused the natives such as the Iroquoians to view the building methods of the colonists as odd as almost all of their building was done with unfinished materials such as branches, bark and tree trunks.[49] The buildings in the city of Montreal remained wooden until the year 1664 when Louis XIV declared the colony an officially recognized province.

This declaration led to the introduction of ‘king’s engineers’ to New France and to Montreal. This led to actual city layout planning and a shift to stone buildings as well.[49] The government of Montreal helped plan the layout of the city; several aspects of the design of the city in the French colonial period are still present. The Sulpicians, who became the seigneurs of Montreal in 1663, perhaps played the largest role in the early formation of the city.[50] The Sulpicians helped design Montreal's chequerboard city plan decided upon in 1671 and with the help of the king's engineers the establishment of stone buildings also began.[51] For example, Father Superior of the Sulpicians Dollier de Casson and surveyor Bénigne Basset originally planned Rue Notre Dame to be the main street of Montreal in 1672.[52] The designers themselves were all similar to the Father Superior not architects by profession and so the engineers worked closely with the religious order to design and build Montreal. Casson for example also designed the Old Sulpician Seminary, the oldest standing building in Montreal and home to the oldest gardens in North America, in 1684.[53]

The lack of architects led to the lack of classical metropolitan form common in France and so many buildings had more basic designs.[49] The workers did improve however and as stonemasons became more skilled and stone more available stone buildings became more common.[49] Stonemasons became the men in charge when in came to building as their resource was of the highest demand and what ever could be done without stone was, this had some unfortunate side effects though as fires in Montreal became common. When more stone was used, the issue arose of cracking as the cold and heat expansion stressed the stone this led to the discovery of a basic plan, which worked for the environment and uniformity in buildings. The roofs in Montreal were designed to be of a sharp pitch and they were topped not with slate, which common in France, but were uncommon in Montreal, and they used cedar shingles and the cheaper method of Canadian-style sheet metal roofing.[49] The Château Ramezay, which was built in 1705 as the residence for then-Governor Claude de Ramezay was built with these building styles.[54]

Canadian-specific architecture in Montreal began to evolve and form after the fire ordinances in 1721, as wood was removed as much as possible from dwellings and left buildings almost completely stone.[51] This also eliminated the common wooden fashionable extras and designs common in France. This caused only churches truly to have any form of decoration on them and caused many of the colonial buildings to be plain. This lack of artistic expression to demonstrate wealth caused many of the wealthy simply to build larger buildings to demonstrate their greatness. This caused a large boom in the demand for stone and an increase in the size of Montreal.[55]

French military history of Montreal

In 1645, a fort was established on the island of Montreal and this was the beginning of Montreal's military history. The fort was key and effective in repelling the raids of the Iroquois and would become a station for soldiers for years to come.[56] After the arrival of Maisonneuve in the Second Foundation in 1653, Montreal became a front for activity throughout New France and a key launching point for expeditions into the frontier.[57] Montreal did not become reinforced however until after the establishment of New France as a province and the welcoming of the ‘king’s engineers’ who came with the military reinforcements. Many of the expeditions who went out to explore Ontario and the Ohio River Valley would start in Montreal, but much of the time in the beginning they would not make it far or they would be forced to return by hostile native forces.[58]

During the early 1700s, many military expeditions left from Montreal to finally deal with the Hostile natives and to strengthen alliances with the Native allies. This led to one of the most significant events to occur in Montreal during this period was the Great Peace of 1701. The conference took place in August and was between the French and representatives of thirty-nine different Aboriginal nations. For the conference an estimated 2000-3000 people (including roughly 1300 native delegates) entered a theatre south of Pointe-à-Callière to listen to speeches given by French leaders and native chiefs.[59] The French engaged in many Aboriginal gestures of peace, including the burying of hatchets, the exchange of wampum belts, and the use of peace pipes.[60] While the French signed their names using their alphabet, the Aboriginal leaders notably used totem symbols to sign the treaty.[61]

The Great Peace resulted in an end to the Iroquois Wars and, according to historian Gilles Havard, "ostensibly (brought) peace to the vast territory extending from Acadia in the East to the Mississippi in the west, and from James Bay in the north to Missouri in the south".[62] The French had hoped to form a military frontier with their Native allies along the borders on New France against the advancing British colonies. The military thus established many forts along the ‘borders’ down the Ohio Valley into New Orleans.[63] Many of these such as Detroit relied on Montreal to reinforce them with supplies and military men furthering Montreal's military involvement and development.

Due to the importance of Montreal to New France the city walls, a double wall 6.4 metres tall and over three kilometres long was erected in 1737 (after twenty years of construction) to protect the city. Only some of the base of the wall remains today.[64] This helped make Montreal the most militarily capable town in New France, and so when the seven years war started Montreal was declared the military headquarters for operations in the North American Theatre.[65] As the military headquarters, the number of military men in Montreal began to increase and the town itself was further expanded and stressed Montreal for supplies.

In 1757 the number of soldiers and natives stationed in Montreal had gotten so great that Pierre de Rigaud de Vaudreuil the Governor of New France realized they needed to take action on a campaign or the army and the town would begin to suffer from starvation. This led to the great campaign of 1757 and with his large force of native allies and the bronzed soldiery of France General Louis-Joseph de Montcalm moved the large force out of Montreal and left a garrison in its place, relieving the pressure on the city to supply the military slightly.[66] Montcalm was very successful in his military efforts keeping spirits in Montreal high and the people hopeful. After his victory at Carillon, Montcalm returned to Montreal; having just defeated 16,000 British forces Montcalm seemed to be in a good position.[67] This would prove false, because of Montcalm's lack of troops in comparison to the British. Learning of an invasion coming over the Saint Laurence, Montcalm took his forces to reinforce Quebec City.[68] Montcalm would die there and Quebec City would be lost, which caused a major shock in Montreal as it now seemed they were doomed and though the city was also briefly established as the capital, but with three British armies headed for it, the town would not last long. In September 1760, the French forces finally capitulated to the British and the French colonial rule ended in Montreal.

British rule and the American Revolution

Ville-Marie remained a French settlement until 1760, when Pierre de Rigaud, marquis de Vaudreuil-Cavagnial surrendered it to the British army under Jeffery Amherst after a two month campaign. With Great Britain's victory in the Seven Years' War, the Treaty of Paris in 1763 marked its end, with the French being forced to cede Canada and all its dependencies to the other nation.[69]

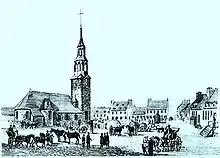

As a British colony, and with immigration no longer limited to members of the Roman Catholic religion, the city began to grow from British immigration. American Revolutionists under General Richard Montgomery briefly captured the city during the 1775 invasion of Canada but left when it became obvious they could not hold Canada.[70] Often having suffered loss of property and personal attacks during hostilities, thousands of English-speaking Loyalists migrated to Canada from the American colonies during and after the American Revolution. In 1782, John Molson estimated the population of the city at 6,000.[71] The government provided most with land, settling them in what became Upper Canada (Ontario) to the west, as well as Nova Scotia and New Brunswick to the east. The first Protestant church in Montreal was St. Gabriel's, established by a Presbyterian missionary in 1792.[72] With 19th-century immigration, more and more English-speaking merchants and residents continued to arrive in what had by then become known as Montreal. Soon the main language of commerce in the city was English. The golden era of fur trading began in the city with the advent of the locally owned North West Company, the main rival to the primarily British Hudson's Bay Company. The first machine shop in Montreal, owned by one George Platt, was in operation before 1809.[73] The census of 1821 numbered 18,767 residents.[74]

The town's population was majority Francophones until around the 1830s. From the 1830s, to about 1865, it was inhabited by a majority of Anglophones, most of recent immigration from the British Isles or other parts of British North America. Fire destroyed one quarter of the town on May 18, 1765.

Scottish contributions

Scottish immigrants constructed Montreal's first bridge across the Saint Lawrence River and founded many of the city's great industries, including Henry Morgan's department store Morgan's, the first in Canada, incorporated within the Hudson's Bay Company in the 1970s; the Bank of Montreal; Redpath Sugar; and both of Canada's national railroads. The city boomed as railways were built to New England, Toronto, and the west, and factories were established along the Lachine Canal. Many buildings from this time period are concentrated in the area known today as Old Montreal. Noted for their philanthropic work, Scots established and funded numerous Montreal institutions, such as McGill University, the Literary and Historical Society of Quebec, the High School of Montreal, and the Royal Victoria Hospital.

The City of Montreal

Montreal was incorporated as a city in 1832. The city's growth was spurred by the opening of the Lachine Canal, which permitted ships to pass by the unnavigable Lachine Rapids south of the island. As the capital of the United Province of Canada from 1844 to 1849, Montreal attracted more English-speaking immigrants: Late Loyalists, Irish, Scottish, and English. The population of Montreal grew from 40,000 in 1841 to 57,000 a decade later.[75]

Riots led by Tories led to the burning of the Provincial Parliament. Rather than rebuild, the government chose Toronto as the new capital of the colony.[76] In Montreal the Anglophone community continued to build McGill, one of Canada's first universities, and the wealthy continued to build large mansions at the foot of Mount Royal as the suburbs expanded.

Long before the Royal Military College of Canada was established in 1876, there were proposals for military colleges in Canada. Staffed by British Regulars, adult male students underwent a 3-month-long military course in Montreal in 1865 at the School of Military Instruction in Montreal. Established by Militia General Order in 1865, the school enabled Officers of Militia or Candidates for Commission or promotion in the Militia to learn Military duties, drill and discipline, to command a Company at Battalion Drill, to Drill a Company at Company Drill, the internal economy of a Company and the duties of a Company's Officer.[77] The school was retained at Confederation, in 1867. In 1868, The School of Artillery was formed in Montreal.[78]

American Civil War

Montréal's status as a major inland port with direct connections to Britain and France made it a valuable asset for both sides of the American Civil War. While Confederate troops secured arms and supplies from the friendly British, Union soldiers and agents spied on their activity while similarly arranging for weapons shipments from France. John Wilkes Booth spent some time in Montréal prior to assassinating President Lincoln, and in one case was said to have drunkenly gallivanted throughout the city telling anyone who would listen of his plan to kill Lincoln. Almost all took him to be a fool. After the War, President of the Confederacy Jefferson Davis stayed at a manor house located at the current site of The Bay on Sainte-Catherine's Street West; a plaque commemorating the site was installed on the West wall of the building, on Union Avenue, in 1957 by the United Daughters of the Confederacy. The plaque was removed in 2017.

Industrialization

The Lachine Canal and major new businesses linked the established port of Montreal with continental markets and led to rapid industrialization during the mid-19th century. The economic boom attracted French Canadian labourers from the surrounding countryside to factories in satellite cities such as Saint-Henri and Maisonneuve. Irish immigrants settled in tough working-class neighbourhoods such as Pointe-Saint-Charles and Griffintown, making English and French linguistic groups roughly equal in size. The growing city also attracted immigrants from Italy, and Eastern Europe.[79]

In 1852, Montreal had 58,000 inhabitants and by 1860, Montreal was the largest city in British North America, and it was the undisputed economic and cultural centre of Canada. From 1861 to the Great Depression of 1930, Montreal developed in what some historians call its Golden Age. Saint Jacques Street became the most important economic centre of the Dominion of Canada. The Canadian Pacific Railway made its headquarters there in 1880, and the Canadian National Railway in 1919. At the time of its construction in 1928, the new head office of the Royal Bank of Canada at 360 St. James Street was the tallest building in the British Empire. With the annexation of neighbouring towns between 1883 and 1918, Montreal became a mostly Francophone city again. The tradition of alternating between a francophone and an anglophone mayor began, lasting until 1914.

Montreal shared control of the Canadian securities market with Toronto from the 1850s to the 1970s causing a persistent rivalry between the two. The financiers were Anglophones. However both cities were overshadowed by London and later New York, for they had easy access to these much larger financial centres.[80]

1914–1939

Montrealers volunteered to serve in the army in the early days of World War I, but most French Montrealers opposed mandatory conscription and enlistment fell off. After the war, the Prohibition movement in the United States turned Montreal into a destination for Americans looking for alcohol. Americans went to Montreal for its drinking, gambling, and prostitution, unrivalled in North America at this time, which earned the city the nickname "Sin City".[81]

Montreal had a population of 618,000 in 1921, growing to 903,000 in 1941.

The twenties saw many changes in the city and the introduction of new technologies continued to have a prominent impact. The introduction of the car in large numbers began to transform the nature of the city. The world's first commercial radio station, XWA began broadcasting in 1920. A huge mooring mast for dirigibles was constructed in St. Hubert in anticipation of trans-Atlantic lighter-than-air passenger service, but only one craft, the R-100, visited in 1930 and the service never developed. However, Montreal became the eastern hub of the Trans-Canada Airway in 1939.

Film production became a part of the city activity. Associated Screen News of Canada in Montreal produced two notable newsreel series, "Kinograms" in the twenties and "Canadian Cameo" from 1932 to 1953. The making of documentary films grew tremendously during World War II with the creation of the National Film Board of Canada, in Montreal, in 1939. By 1945 it was one of the major film production studios in the world with a staff of nearly 800 and over 500 films to its credit including the very popular, "The World in Action" and "Canada Carries On", series of monthly propaganda films. Other developments in the cultural field included the founding of Université de Montréal in 1919 and the Montreal Symphony Orchestra in 1934. The Montreal Forum, built in 1924 became the home ice rink of the fabled Montreal Canadiens hockey team.

Dr. Wilder Penfield, with a grant from the US Rockefeller Foundation founded the Montreal Neurological Institute at the Royal Victoria Hospital (Montreal), in 1934 to study and treat epilepsy and other neurological diseases. Research into the design of nuclear weapons was conducted at the Montreal Laboratory of the National Research Council of Canada during World War II.

Great Depression

Unemployment was high during the Great Depression in Canada in the 1930s. Canada began to recover from the Great Depression in the mid-1930s, and real estate developers began to build skyscrapers, changing Montreal's skyline. The Sun Life Building, built in 1931, was for a time the tallest building in the British Commonwealth. During World War II its vaults were used as the hiding place for the gold bullion of the Bank of England and the British Crown Jewels.

With so many men unemployed women had to scrimp on spending to meet the reduced family budget. About a fourth of the workforce were women, but most women were housewives. Denyse Baillargeon uses oral histories to discover how Montreal housewives handled shortages of money and resources during the depression years. Often they updated strategies their mothers used when they were growing up in poor families. Cheap foods were used, such as soups, beans and noodles. They purchased the cheapest cuts of meat—sometimes even horse meat and recycled the Sunday roast into sandwiches and soups. They sewed and patched clothing, traded with their neighbours for outgrown items, and kept the house colder. New furniture and appliances were postponed until better days. These strategies, Baillargeon finds, show that women's domestic labour—cooking, cleaning, budgeting, shopping, childcare—was essential to the economic maintenance of the family and offered room for economies. Most of her informants also worked outside the home, or took boarders, did laundry for trade or cash, and did sewing for neighbours in exchange for something they could offer. Extended families used mutual aid—extra food, spare rooms, repair-work, cash loans—to help cousins and in-laws.[82] Half of the Catholic women defied Church teachings and used contraception to postpone births—the number of births nationwide fell from 250,000 in 1930 to about 228,000 and did not recover until 1940.[83]

Second World War

Canada declared war on Germany in September 1939, and the result was an economic boom that ended the last traces of depression. Mayor Camillien Houde protested against conscription. He urged Montrealers to ignore the federal government's registry of all men and women because he believed it would lead to conscription. The federal government at Ottawa, considering Houde's actions treasonable, incarcerated him in a prison camp in Petawawa, Ontario, for over four years, from 1940 until 1944. That year the government instituted conscription in order to expand the armed forces to confront the Axis Powers. (see Conscription Crisis of 1944).

The Quiet Revolution and the modernization of Montreal

By the beginning of the 1960s, a new political movement was rising in Quebec. The newly elected Liberal government of Jean Lesage made reforms that helped francophone Quebecers gain more influence in politics and in the economy, thus changing the city. More francophones began to own businesses as Montreal became the centre of French culture in North America.

From 1962 to 1964, four of Montreal's ten tallest buildings were completed: Tour de la Bourse, Place Ville-Marie, the CIBC Building and CIL House. Montreal gained an increased international status due to the World's Fair of 1967, known as Expo 67, for which innovative construction such as Habitat was completed. During the 1960s, mayor Jean Drapeau carried upgraded infrastructure throughout the city, such as the construction of the Montreal Metro, while the provincial government built much of what is today's highway system. Like many other North American cities during these years, Montreal had developed so rapidly that its infrastructure was lagging behind its needs.

In 1969, a police strike resulted in 16 hours of unrest, known as the Murray Hill riot.[84] Police were motivated to strike because of difficult working conditions caused by disarming separatist-planted bombs and patrolling frequent protests and wanting higher pay.[84] The National Assembly of Quebec passed an emergency law forcing the police back to work. By the time order was restored, 108 people had been arrested.[84]

The 1976 Summer Olympics, officially known as the "Games of the XXI Olympiad", held in Montreal, was the first Olympics in Canada. The Games helped introduce Quebec and Canada to the rest of the world. The entire province of Quebec prepared for the games and associated activities, generating a resurgence of interest in amateur athletics across the province. The spirit of Québec nationalism helped motivate the organizers; however, the city went $1 billion into debt.[85][86]

Quebec Independence Movement

At the end of the 1960s, the independence movement in Quebec was in full swing due to a constitutional debate between the Ottawa and Quebec governments. Radical groups formed, most notably the Front de libération du Québec (FLQ). In October 1970, members of the FLQ's "Liberation Cell" kidnapped and murdered Pierre Laporte, a minister in the National Assembly, and also kidnapped James Cross, a British diplomat, who was later released. The Prime Minister of Canada, Pierre Trudeau, ordered the military occupation of Montreal and invoked the War Measures Act, giving unprecedented peacetime powers to police. The social unrest and related events became known as the October Crisis of 1970.

Sovereignty was addressed through the ballot box. The Parti Québécois held two referendums on the question, in 1980 and in 1995. During those decades, about 300,000 English-speaking Quebecers left Quebec. The uncertain political climate caused substantial social and economic impacts, as a significant number of Montrealers, mostly Anglophone, took their businesses and migrated to other provinces. The extent of the transition was greater than the norm for major urban centres. With the passage of Bill 101 in 1977, the government gave primacy to French as the only official language for all levels of government in Quebec, the main language of business and culture, and the exclusive language for public signage and business communication. In the rest of Canada, the government adopted a bilingual policy, producing all government materials in both French and English. The success of the separatist Parti Québécois caused uncertainty over Quebec's economic future, leading to an exodus of corporate headquarters to Toronto and Calgary.[87]

In recent years, Quebecois Independence has had a surge of popularity as the Bloc Québécois, the leading Quebecois separatist party, won 7.7% of the vote in the 2019 election[88] which is a 63% increase from the 2015 election.[89]

Economic recovery

During the 1980s and early 1990s, Montreal experienced a slower rate of economic growth than many other major Canadian cities. By the late 1990s, however, Montreal's economic climate had improved, as new firms and institutions began to fill the traditional business and financial niches.[90]

As the city celebrated its 350th anniversary in 1992, construction began on two new skyscrapers: 1000 de La Gauchetière and 1250 René-Lévesque. Montreal's improving economic conditions allowed further enhancements of the city infrastructure, with the expansion of the metro system, construction of new skyscrapers, and the development of new highways, including the start of a ring road around the island. The city attracted several international organisations that moved their secretariats into Montreal's Quartier International: International Air Transport Association (IATA), International Council of Societies of Industrial Design (Icsid), International Council of Graphic Design Associations (Icograda), International Bureau for Children's Rights (IBCR), International Centre for the Prevention of Crime (ICPC) and the UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS). With developments such as Centre de Commerce Mondial (World Trade Centre), Quartier International, Square Cartier, and proposed revitalization of the harbourfront, Montreal is regaining its international position as a world-class city.

Merger and demerger

The concept of having one municipal government for the island of Montreal was first proposed by Jean Drapeau in the 1960s. The idea was strongly opposed in many suburbs, although Rivière-des-Prairies, Saraguay (Saraguay) and Ville Saint Michel (now the Saint-Michel neighbourhood) were annexed to Montreal between 1963 and 1968. Pointe-aux-Trembles was annexed in 1982.

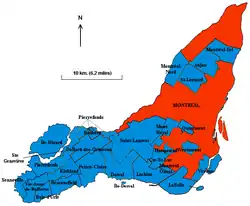

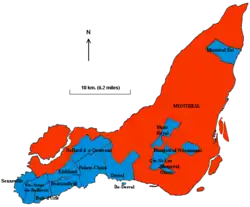

In 2001, the provincial government announced a plan to merge major cities with their suburbs. As of January 1, 2002, the entire Island of Montreal, home to 1.8 million people, as well as the several outlying islands that were also part of the Montreal Urban Community, were merged into a new "megacity". Some 27 suburbs as well as the former city were folded into several boroughs, named after their former cities or (in the case of parts of the former Montreal) districts.

During the 2003 provincial elections, the winning Liberal Party had promised to submit the mergers to referendums. On June 20, 2004, a number of the former cities voted to demerge from Montreal and regain their municipal status, although not with all the powers they once had. The following voted to demerge: Baie-d'Urfé, Beaconsfield, Côte Saint-Luc, Dollard-des-Ormeaux, Dorval, the uninhabited L'Île-Dorval, Hampstead, Kirkland, Montréal-Est, Montreal West, Mount Royal, Pointe-Claire, Sainte-Anne-de-Bellevue, Senneville, and Westmount. The demergers were effective on January 1, 2006.

Anjou, LaSalle, L'Île-Bizard, Pierrefonds, Roxboro, Sainte-Geneviève, and Saint-Laurent had majority votes in favour of demerger, but their turnout of voters was insufficient to meet the requirements for the decision, so those former municipalities remained part of Montreal. No referendum was held in Lachine, Montréal-Nord, Outremont, Saint Leonard, or Verdun - nor in any of the boroughs that were part of the former city of Montreal.

The Island of Montreal now has 16 municipalities (the city of Montreal proper plus 15 independent municipalities). The post-demerger city of Montreal (divided into 19 boroughs) has a territory of 366.02 km2 (141.32 sq mi) and a population of 1,583,590 inhabitants (based on 2001 census figures). Compared with the pre-merger city of Montreal, this is a net increase of 96.8% in land area, and 52.3% in population.

The city of Montreal with its current boundaries now has nearly as many inhabitants as the former unified city of Montreal (the recreated suburban municipalities are less densely populated than the core city), but population growth is expected to be slower for some time. Analysts note that the overwhelming majority of industrial sites are located in the territory of the post-demerger city of Montreal. The current city of Montreal is about half the size of the post-1998 merger city of Toronto (both in terms of land area and population).

The 15 recreated suburban municipalities have fewer government powers than they did before the merger. A joint board covering the entire Island of Montreal, in which the city of Montreal has the upper hand, retains many powers.

Despite the demerger referendums held in 2004, controversy continues as some politicians note the cost of demerging. Several studies show that the recreated municipalities will incur substantial financial costs, which will require them to increase taxes (an unanticipated result for the generally wealthier English-speaking municipalities that had voted for demerger). Proponents of the demergers contest the results of such studies. They note that reports from other merged municipalities across the country that show that, contrary to their primary raison d'être, the fiscal and societal costs of mega-municipalities far exceed any projected benefit.

Origin of the name

During the early 18th century, the name of the island came to be used as the name of the town. Two 1744 maps by Nicolas Bellin identified the island as Isle de Montréal and the town as Ville-Marie; but a 1726 map refers to the town as "la ville de Montréal". The name Ville-Marie soon fell into disuse. Today it is used to refer to the Montreal borough that includes downtown.

In the modern Mohawk language, Montreal is called Tiohtià:ke. In Algonquin, it is called Moniang.[91]

See also

Notes

- ↑ Erin Hurley (2011). National Performance: Representing Quebec from Expo 67 to Céline Dion. U of Toronto Press. p. 58. ISBN 9781442640955.

- ↑ "Place Royale and the Amerindian presence". Société de développement de Montréal. September 2001. Retrieved 2007-03-09.

- 1 2 Tremblay, Roland (2006). The Saint Lawrence Iroquoians. Corn People. Montréal, Qc: Les Éditions de l'Homme.

- ↑ Google books accessed December 23, 2007

- 1 2 Auger, Roland J. (1955). La Grande Recrue de 1653. Montreal.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help)CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ "The Exhaustion of the Iroquois". The Compagnies Franches de la Marine of Canada. Government of Canada. 2004-06-20. Archived from the original on 2007-09-11. Retrieved 2007-08-02.

- ↑ "The Shock of the Attack on Lachine". The Compagnies Franches de la Marine of Canada. Department of National Defence, Canada. 2004-06-20. Archived from the original on 2006-12-07. Retrieved 2007-01-23.

- ↑ Yves F. Zoltvany, The Government of New France: Royal, Clerical, or Class Rule? (Scarborough: Prentice-Hall of Canada, 1971), 4.

- ↑ Robert Stanley Weir, The Administration of the Old Regime in Canada (Montreal: L.E. and A.F. Waters, 1897), 68.

- ↑ Zoltvany, 4-5.

- 1 2 Zoltvany 5.

- ↑ Weir, 86.

- ↑ Louise Dechêne, Habitants and Merchants in Seventeenth-Century Montreal, trans, Liana Vardi, (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1992), 7

- ↑ Dechêne, Habitants and Merchants, 7

- 1 2 3 4 5 Dechêne, Habitants and Merchants, 16

- ↑ Dechêne, Habitants and Merchants, 46

- ↑ Dechêne, Habitants and Merchants, 26

- ↑ Dechêne, Habitants and Merchants, 25

- ↑ Dechêne, Habitants and Merchants, 19

- ↑ Dechêne, Habitants and Merchants, 17

- 1 2 Dechêne, Habitants and Merchants, 36

- ↑ Dechêne, Habitants and Merchants, 44

- 1 2 3 Dechêne, Habitants and Merchants, 47

- ↑ Dechêne, Habitants and Merchants, 62

- ↑ Dechêne, Habitants and Merchants, 60

- ↑ Dechêne, Habitants and Merchants, 57

- ↑ Dechêne, Habitants and Merchants, 61

- 1 2 3 Dechêne, Habitants and Merchants, 66

- 1 2 3 Dechêne, Habitants and Merchants, 78

- ↑ Dechêne, Habitants and Merchants, 80

- 1 2 3 4 Dechêne, Habitants and Merchants, 81

- ↑ Constructing Early Modern Empires: Proprietary Ventures in the Atlantic World, 1500-1750. BRILL. 23 February 2007. pp. 121–. ISBN 978-90-474-1903-7.

- 1 2 Dechêne, Habitants and Merchants, 74

- ↑ Guy Fregault, La Compagnie de la Colonie, 30:(Universite d’Ottawa: Ottawa, 1960),1

- ↑ Dechêne, Habitants and Merchants, 4

- ↑ Dechêne, Habitants and Merchants, 10

- ↑ Dechêne, Habitants and Merchants, 6

- ↑ Dechêne, Habitants and Merchants, 5

- 1 2 Dechêne, Habitants and Merchants, 9

- ↑ Dechêne, Habitants and Merchants, 188

- 1 2 Dechêne, Habitants and Merchants, 192

- ↑ Dechêne, Habitants and Merchants, 192-193

- ↑ Dechêne, Habitants and Merchants, 193

- ↑ Jean Lunn, The Illegal Fur Trade Out of New France 1713-60 (McGill University: Montreal, 1939) 61

- ↑ Lunn, Illegal Fur Trade, 66

- ↑ Lunn, Illegal Fur Trade, 61

- ↑ Lunn, Illegal Fur Trade, 64

- 1 2 Lunn, Illegal Fur Trade, 65

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Morisset, Lucie K., and Luc Noppen. "Architectural History: The French Colonial Régime." The Canadian Encyclopedia. Historica-Dominion Institute, 2012. Feb. 2013.

- ↑ "The Old Seminary and Notre-Dame Basilica," Old Montreal, last modified September 2001, http://www.vieux.montreal.qc.ca/tour/etape17/eng/17fena.htm.

- 1 2 Robert, Jean-Claude. Atlas Historique De Montréal. Montréal, Québec: Art Global, 1994.

- ↑ "Central Rue Notre-Dame West," Old Montreal, last modified September 2001, http://www.vieux.montreal.qc.ca/tour/etape18/eng/18fena.htm.

- ↑ "The Old Seminary and Notre-Dame Basilica."

- ↑ "Rue Notre-Dame East," Old Montreal, last modified September 2001, http://www.vieux.montreal.qc.ca/tour/etape2/eng/2text5a.htm.

- ↑ Morisset, Lucie K., and Luc Noppen. "Architectural History: The French Colonial Régime." The Canadian Encyclopedia. Historica-Dominion Institute, 2012. Web. Feb. 2013.

- ↑ Atherton, William H. Montreal, 1535-1914. (Montreal: S.J. Clarke,, 1914), 92

- ↑ Atherton, Montreal, 111

- ↑ Atherton, Montreal, 124

- ↑ Gilles Havard, Montreal, 1701: Planting the Tree of Peace (Montreal: Recherches Amérindiennes au Québec, 2001), 42-43.

- ↑ Havard, 44.

- ↑ Havard, 47

- ↑ Havard, 11

- ↑ Atherton, Montreal, 315

- ↑ "Champ-de-Mars," Old Montreal, last modified September 2001, http://www.vieux.montreal.qc.ca/tour/etape1/eng/1text2a.htm.

- ↑ Atherton, Montreal, 391

- ↑ Atherton, Montreal, 404

- ↑ Atherton, Montreal,419

- ↑ Atherton, Montreal, 428

- ↑ "His Most Christian Majesty cedes and guaranties to his said Britannick Majesty, in full right, Canada, with all its dependencies, as well as the island of Cape Breton, and all the other islands and coasts in the gulph and river of St. Lawrence, and in general, every thing that depends on the said countries, lands, islands, and coasts, with the sovereignty, property, possession, and all rights acquired by treaty, or otherwise, which the Most Christian King and the Crown of France have had till now over the said countries, lands, islands, places, coasts, and their inhabitants" – Treaty of Paris, 1763

- ↑ "The Invasion of Canada and the Fall of Boston". americanrevolution.com. Retrieved 2007-08-02.

- ↑ Denison 1955, p. 21

- ↑ Denison 1955, p. 48

- ↑ Denison 1955, p. 64

- ↑ Denison 1955, p. 136

- ↑ Denison 1955, p. 183

- ↑ "Walking Tour of Old Montreal". Véhicule Press. Retrieved 2008-01-30.

- ↑ "Anson Keill's Second class certificate from the School of Military Instruction, Kingston". Archived from the original on 2016-04-07. Retrieved 2016-01-22.

- ↑ Richard Preston 'Canada's RMC: A History of the Royal Military College of Canada' published by the RMC Club by U of Toronto Press.

- ↑ John Powell (2009). Encyclopedia of North American Immigration. Infobase Publishing. pp. 194–95. ISBN 9781438110127.

- ↑ Ranald C. Michie, "The Canadian Securities Market, 1850–1914," Business History Review (1988), 62#1 pp 35–73. 39p

- ↑ "Lonely Planet Montreal Guide - Modern History". Lonely Planet. Retrieved 2007-08-02.

- ↑ Denyse Baillargeon, Making Do: Women, Family and Home in Montreal during the Great Depression (Wilfrid Laurier U. Press, 1999) pp 70, 108, 136–38, 159.

- ↑ M. C. Urquhart (1965). Historical statistics of Canada. Toronto: Macmillan. p. 38.

- 1 2 3 "CBC Archives".

- ↑ Patrick Allen, "Les Jeux Olympiques: Icebergs ou Rampes de Lancements?," [The Olympic Games: Icebergs or launching pads?] Action Nationale (1976) 65#5 pp 271-323

- ↑ Paul Charles Howell, The Montreal Olympics: An Insider's View of Organizing a Self-financing Games (Montréal: McGill-Queens University Press, 2009)

- ↑ Mark J. Kasoff; Patrick James (2013). Canadian Studies in the New Millennium (2nd ed.). University of Toronto Press. p. 9. ISBN 9781442665385.

- ↑ "Canada election 2019: Results from the federal election". Global News.

- ↑ "2015 Federal Election Results". CBC.

- ↑ Brooke, James (2000-05-06). "Montreal Journal; No Longer Fading, City Booms Back Into Its Own". New York Times. Retrieved 2008-04-12.

- ↑ Geonames Archived 2008-05-31 at the Wayback Machine

Further reading

In English

- Atherton, William H. Montreal, 1535-1914. Montreal: S.J. Clarke, 1914.

- Blais-Tremblay, Vanessa. Jazz, Gender, Historiography: a Case Study of the" Golden Age" of Jazz in Montreal (1925–1955) (McGill University, 2018).

- Cooper, John Irwin. (1969). Montreal, a Brief History, McGill-Queen's University Press, 217 pages

- Dechêne, Louise. (1992). Habitants and Merchants in Seventeenth-Century Montreal, McGill-Queen's Press, 428 pages ISBN 0-7735-0951-8 (online excerpt)

- Denison, Merrill (1955). The Barley and the Stream: The Molson Story. McClelland & Stewart Limited.

- Dollier de Casson, François (1928). A History of Montreal 1640-1672, New York: Dutton & Co., 384 pages

- Havard, Gilles. Montreal, 1701: Planting the Tree of Peace. Montreal: Recherches Amérindiennes au Québec, 2001.

- Jenkins, Kathleen. Montreal: Island City of the St Lawrence (1966), 559pp.

- Linteau, Paul-André, and Peter McCambridge. The History of Montreal: The Story of Great North American City (2013) excerpt; 200pp

- Lunn, Jean. The Illegal Fur Trade Out of New France 1713-60. Montreal: McGill University, 1939.

- Marsan, Jean-Claude. (1990). Montreal in Evolution. Historical Analysis of the Development of Montreal's Architecture and Urban Environment, McGill-Queen's Press, 456 pages ISBN 0-7735-0798-1 (online excerpt)

- McLean, Eric, R. D. Wilson (1993). The Living Past of Montreal, McGill-Queen's Press, 60 pages ISBN 0-7735-0981-X (online excerpt)

- Morisset, Lucie K., and Luc Noppen. "Architectural History: The French Colonial Régime." The Canadian Encyclopedia. Historica-Dominion Institute, 2012. Feb. 2013.

- Olson, Sherry H. and Patricia A. Thornton, eds. Peopling the North American City: Montreal, 1840–1900. Carleton Library Series. Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press, 2011. 524 pp. online review

- Simpson, Patricia. (1997). Marguerite Bourgeoys and Montreal, 1640-1665, McGill-Queen's University Press, 247 pages ISBN 0-7735-1641-7 (online excerpt)

- Vineberg, Robert. "The British Garrison and Montreal Society, 1830-1850." Canadian Military History 21.1 (2015): online

- Weir, Robert Stanley. The Administration of the Old Regime in Canada. Montreal: L.E. and A.F. Waters, 1897.

- Zoltvany, Yves F. The Government of New France: Royal, Clerical, or Class Rule? Scarborough: Prentice-Hall of Canada, 1971.

Older sources: full text online

- The Montreal Almanack, Or, Lower Canada Register for 1831: Being Third After Leap Year. R. Armour. 1831. p. 96.

- General Review of the Trade of Montreal: Also, A Synopsis of the Commerce of Canada, and an Essay Upon Protection for Home Manufactures. T.&R. White. 1877.

- John McConniff (1890). Illustrated Montreal: The Metropolis of Canada. Its Romantic History, Its Beautiful Scenery, Its Grand Institutions, Its Present Greatness, Its Future Splendour.

- John Douglas Borthwick (1892). History and Biographical Gazetteer of Montreal to the Year 1892. John Lovell.

- Montreal, Bank of (1917). The Centenary of the Bank of Montreal, 1817-1917.

In French

- Desjardins, Pauline, and Geneviève Duguay (1992). Pointe-à-Callière—from Ville-Marie to Montreal, Montreal: Les éditions du Septentrion, 134 pages ISBN 2-921114-74-7 (online excerpt)

- Deslandres, Dominique et al., ed. (2007). Les Sulpiciens de Montréal : Une histoire de pourvoir et de discrétion 1657-2007, Éditions Fides, 670 pages ISBN 2-7621-2727-0

- Fregault, Guy. La Compagnie de la Colonie, University of Ottawa: Ottawa, 1960.

- Lauzon, Gilles and Forget, Madeleine, ed. (2004). L’histoire du Vieux-Montréal à travers son patrimoine, Les Publications du Québec, 292 pages ISBN 2-551-19654-X

- Linteau, Paul-André (2000). Histoire de Montréal depuis la Confédération. Deuxième édition augmentée, Éditions du Boréal, 622 pages ISBN 2-89052-441-8

- Ville de Montréal (1995). Les rues de Montréal : Répertoire historique, Éditions du Méridien, 547 pages

- Darsigny, Maryse et al., ed. (1994). Ces femmes qui ont bâti Montréal, Éditions du Remue-Ménage, 627 pages ISBN 2-89091-130-6

- Marsolais, Claude-V. et al., (1993). Histoire des maires de Montréal, VLB Éditeur, Montréal, 323 pages ISBN 2-89005-547-7

- Burgess, Johanne et al., ed. (1992) Clés pour l’histoire de Montréal, Éditions du Boréal, 247 pages ISBN 2-89052-486-8

- Benoît, Michèle and Gratton, Roger (1991). Pignon sur rue : Les quartiers de Montréal, Guérin 393 pages ISBN 2-7601-2494-0

- Landry, Yves, ed. (1992). Pour le Christ et le Roi : La vie aux temps des premiers montréalais, Libre Expression, 320 pages ISBN 2-89111-523-6

- Linteau, Paul-André (1992). Brève histoire de Montréal, Éditions du Boréal 165 pages ISBN 2-89052-469-8

- Robert, Jean-Claude. Atlas Historique De Montréal. Montréal: Art Global, 1994.

External links

- Old Montreal. "Central Rue Notre-Dame West." Last modified September 2001. http://www.vieux.montreal.qc.ca/tour/etape18/eng/18fena.htm.

- Old Montreal. "Champ-de-Mars." Last modified September 2001. http://www.vieux.montreal.qc.ca/tour/etape1/eng/1text2a.htm.

- Old Montreal. "The Old Seminary and Notre-Dame Basilica." Last modified September 2001. http://www.vieux.montreal.qc.ca/tour/etape17/eng/17fena.htm.

- Old Montreal."Rue Notre-Dame East." Last modified September 2001. http://www.vieux.montreal.qc.ca/tour/etape2/eng/2text5a.htm.