Vizcaya | |

Vizcaya Museum and Gardens in February 2011 | |

| |

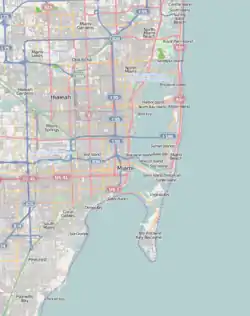

| Location | 3251 South Miami Avenue Miami, Florida, U.S. |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 25°44′37″N 80°12′37″W / 25.74361°N 80.21028°W |

| Area | 43 acres (17 ha) |

| Built | 1914–23[1] |

| Architect | F. Burrall Hoffman (architect), Paul Chalfin (designer), and Diego Suarez (landscape architect)[1] |

| Architectural style | Mediterranean Revival Style; with Baroque,[2] Italian Renaissance,[1] Italian Renaissance Revival[3] |

| NRHP reference No. | 70000181[4] (original) 78003193 (increase) |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | September 29, 1970[4] |

| Boundary increase | November 15, 1978 |

| Designated NHLD | April 19, 1994[2] |

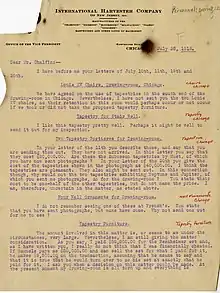

The Vizcaya Museum and Gardens, previously known as Villa Vizcaya, is the former villa and estate of businessman James Deering, of the Deering McCormick-International Harvester fortune, on Biscayne Bay in the present-day Coconut Grove neighborhood of Miami, Florida. The early 20th-century Vizcaya estate also includes extensive Italian Renaissance gardens, native woodland landscape, and a historic village outbuildings compound.

The landscape and architecture were influenced by Veneto and Tuscan Italian Renaissance models and designed in the Mediterranean Revival architecture style, with Baroque elements. F. Burrall Hoffman was the architect,[5] Iwahiko Tsumanuma (also known as Thomas Rockrise) was the associate architect,[6] Paul Chalfin was the design director, and Diego Suarez was the landscape architect.[7]

Miami-Dade County now owns the Vizcaya property, as the Vizcaya Museum and Gardens, which is open to the public.[8] The location is served by the Vizcaya Station of the Miami Metrorail.

Etymology

The estate's name refers to the northern Spanish province Biscay, "Vizcaya", in the Basque region along the east Atlantic's Bay of Biscay, as the estate is on the west Atlantic's Biscayne Bay. Records indicate Deering wished the name also to commemorate an early Spaniard named Vizcaya who he thought explored the area, although later he was corrected that the explorer's name was Sebastián Vizcaíno. Deering used the caravel, a type of ship style used during the Age of Exploration, as the symbol and emblem of Vizcaya. A representation of the mythical explorer "Bel Vizcaya" welcomes visitors at the entrance to the property.

History

The estate property originally consisted of 180 acres (73 ha) of shoreline mangrove swamps and dense inland native tropical forests. Being a conservationist, Deering sited the development of the estate portion along the shore to conserve the forests. This portion was to include the villa, formal gardens, recreational amenities, expansive lagoon gardens with new islets, potager and grazing fields, and a village services compound. Deering began construction of Vizcaya in 1912, officially beginning occupancy on Christmas Day 1916, when he arrived aboard his yacht Nepenthe.[9][10]

The villa was built primarily between 1914 and 1922, at a cost of $15 million,[11] while the construction of the extensive elaborate Italian Renaissance gardens and village continued into 1923. Deering used Vizcaya as his winter residence from 1916 until his death in 1925. During World War I, building trades and supplies were difficult to acquire in Florida.

Vizcaya is noteworthy for adapting historical European aesthetic traditions to South Florida's subtropical ecoregion. For example, it combined imported French and Italian garden layouts and elements implemented in Cuban limestone stonework with Floridian coral architectural trim and planted with sub-tropic compatible and native plants that thrived in the habitat and climate. Palms and philodendrons had not been represented in the emulated gardens of Tuscany or Île-de-France.

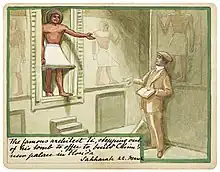

In 1910, interior decorator Elsie de Wolfe introduced[12] Deering to Paul Chalfin,[13] a former art curator, painter, and interior designer, who became the project's director.[2] He assisted and encouraged Deering to collect art items, antiquities, and architectural elements for the project. Chalfin recommended the architect F. Burrall Hoffman[14] to design the structure and facade of the villa, garden pavilions, and estate outbuildings.

In 1914, during a visit to Villa La Pietra in Florence, Deering and Chalfin met[15] Colombian landscape designer Diego Suarez.[16] Suarez, the designer of the landscape master plan and individual gardens, trained with Sir Harold Acton at the gardens of Villa La Pietra.[17]

Vizcaya's villa exterior and garden architecture is a composite of different Italian Renaissance villas and gardens, with French Renaissance parterre features, based on visits and research by Chalfin, Deering, and Hoffman.[18] The villa facade's primary influence is the Villa Rezzonico (it)[19] designed by Baldassarre Longhena at Bassano del Grappa in the Veneto region of northern Italy.[20][21][22] Vizcaya is sometimes referred to as the "Hearst Castle of the East".[23]

Vizcaya Museum also features Gilded Age technology. There are old doorbells, a dumbwaiter, and a rotary-dial telephone. Vizcaya's telephone system was the first in Miami-Dade County.

Deering died in September 1925, on board the steamship SS City of Paris en route back to the United States. After his death Vizcaya was inherited by his two nieces, Marion Deering McCormick, wife of Chauncey McCormick, and Barbara Deering Danielson, wife of Richard Ely Danielson. Over the decades, after hurricanes and increasing maintenance costs, they began selling the estate's surrounding land parcels and outer gardens. In 1945, they sold significant portions of the Vizcaya property to the Catholic Diocese of St. Augustine, Florida, to build Miami's Mercy Hospital. 50 acres (200,000 m2) comprising the main house, the formal gardens, and the village were retained.[17][24]

In 1952, Miami-Dade County acquired the villa and formal Italian gardens, which needed significant restoration, for $1 million. Deering's heirs donated the villa's furnishings and antiquities to the County-Museum.[17][24] Vizcaya began operation in 1953 as the Dade County Art Museum. The village and remaining property were acquired by the county during the mid-1950s. In 1994, the Vizcaya estate was designated a National Historic Landmark.[2] In 1998, in conjunction with Vizcaya's reaccreditation process by the American Alliance of Museums, the Vizcaya Museum and Gardens Trust was formed to be the museum's governing body.

In 1960, the Miami Science Museum and Space Transit Planetarium was built on the area of Vizcaya across from the main building.

1971 robbery

On March 22, 1971, three individuals from New York City stole approximately $1.5 million in artworks and silver items from the Villa Vizcaya, some of which were of historical value.[25] The trio of reputed jewel thieves was arrested on March 25, 1971.[26] Sergeant Tom Connolly from the New York City Police Department raided the Manhattan apartment of Vojislav Stanimirović and his wife, Branka, and arrested them. The couple's accomplice, Alexander Karalanović, was also arrested, and all three were charged with suspicion of stolen property and possession of a dangerous weapon. From the Stanimirovićs' apartment, approximately $250,000 of the stolen goods was recovered. Sergeant Connolly stated that included in the theft was a virtually priceless silver bowl that once belonged to Napoleon Bonaparte.[27] According to Sergeant Connolly, the three perpetrators had been under surveillance for four months for unrelated jewel burglaries that they had carried out in the Manhattan Diamond District. NYPD Captain Thomas Kissane said that the vast majority of the precious items stolen from the Vizcaya were never recovered.

Vizcaya Museum and Gardens

.jpg.webp)

"Miami-Dade in 2017 entered into a long-term operating and management agreement with Vizcaya Museum and Gardens Trust Inc., a local nonprofit. The county still provides funds for “upkeep, maintenance, renovations and operations … in the form of annual budget appropriations and grants.” — Miami-Dade Commissioner Joe Martinez —Miami Today"[8]

The estate is now known officially as the Vizcaya Museum and Gardens, which consists of 50 acres (200,000 m2) with the villa and the gardens, and the remaining native forest. The estate is a total of 50 acres (200,000 m2), of which 10 acres (40,000 m2) contain the Italian Renaissance formal gardens, and 40 acres (160,000 m2) are circulation and the native hammock.[17][28] This beautiful landscape is packed with unique decor and tons of history. The complimentary audio tour provides a great selection-paced tool to explore this marvelous mansion and its surroundings. There are tons of nooks and crannies to explore, making it a great place to spend hours discovering all its wonders.[29]

The villa's museum contains more than seventy rooms of distinctive architectural interiors decorated with numerous antiques, with an emphasis on 15th through early 19th-century European decorative art and furnishings.[17][28] Amongst the furnishings are ceramics, the originals of which were shipped from England in 1912 but sank along with the Titanic. Luckily, Deering had taken out insurance and had them replaced.[30]

Vizcaya was built with an open-air courtyard and extensive gardens on Biscayne Bay. As such, the estate has been subject to environmental and hurricane damage, the latter notably in 1926, 1992, and 2005. Miami-Dade County has granted money ($50 million) for the restoration and preservation of Vizcaya. These funds have been matched by grants from FEMA, Save America's Treasures, and numerous other funders. Plans include restoration of the villa and gardens, and adaptation of the historic village compound for exhibition and educational facilities; however, additional funds are required for this. The completed first phase of the project included rebuilding of the museum's cafe and shop (in historic recreation areas of the building adjacent to the pool), renovation of the North and South Gate Lodges that flank South Miami Avenue, and rebuilding of the David A. Klein Orchidarium in a plan that generally uses historic precedent. At the same time, Vizcaya has completed the first half of a major conservation program of its outdoor sculpture collections. With a consulting landscape architect, Vizcaya has also finished a comprehensive cultural landscape report, which will be a vital tool in the ongoing restoration of the formal gardens.

The Great Miami Hurricane of 1926 devastated the greater Miami area including Vizcaya. The estate's historic rose garden was destroyed after saltwater seeped in, decimating the roses and preventing growth thereafter. Vizcaya's horticultural team partnered with the Tropical Rose Society of Miami to help bring some roses back to Vizcaya's gardens 100 years later. However, the historic rose garden, now known as the fountain garden, has not been returned to its former glory.[31] One of Vizcaya's outdoor restoration project challenges included the estate's swimming pool grotto, built in 1916. The pool is only one of two public places in the world to feature a surviving mural by Robert Winthrop Chanler, a prominent American artist. The ceiling mural was designed in 1916, depicting an underwater fantasy scene filled with creatures and marine life. Shells are embedded into the plaster mural of the scene.[32]

In 1992 and 2005, the swimming grotto was submerged during hurricanes. The combination of floods and Miami's climate have led to preservation challenges and are a priority to the museum. The State of Florida and the Division of Emergency Management's Hurricane Loss Mitigation Program provided Vizcaya with a grant of $194,000 to help prevent future damage to the historic estate.[33]

In 2008 the National Trust for Historic Preservation listed Vizcaya as one of America's Eleven Most Endangered Historic Places.[34] As noted by the National Trust's website, Vizcaya's inclusion on this list was based on the threat of proposed highrise development on neighboring property. Specifically, the National Trust stated: "Unless development is blocked or an intervention occurs, this cultural landscape will be permanently damaged by the construction of three high-rise condominium towers within Vizcaya's historic viewshed."[35] The proposed highrises were blocked by two court rulings and, in 2010, the City of Miami included viewshed protection for historic properties such as Vizcaya in its new zoning code, Miami 21.

Other types of events are hosted by the museum to collect funds for its preservation. For example, every Halloween, Vizcaya organizes a costume party, where people from all around Florida attend in costume.

Vizcaya participates in Baynanza, Biscayne Bay Cleanup Day, an annual community event to clean up the most important ecological system in South Florida. During the event, Vizcaya encourages participants to capture Biscayne Bay's beauty with a photography contest. The event usually takes place on Earth Day.[36]

State occasions

Vizcaya was the 1987 venue where President Ronald Reagan received Pope John Paul II on his first visit to Miami.[37][38]

Vizcaya was the 1994 location of the first 'Summit of the Americas', convened by President Bill Clinton. The thirty-four nations' leaders that met at Vizcaya created the 'Free Trade Area of the Americas (FTAA),' that all the hemisphere's countries, except Cuba, could join for national and corporate trade benefits.

Americans with Disabilities Act

"Vizcaya was a very modern house. Many are surprised to learn that it was built largely of reinforced concrete, with the latest technology of the period, such as generators and a water filtration system. Vizcaya was also equipped with heating and ventilation, two elevators, a dumbwaiter, a central vacuum-cleaning system and a partly automated laundry room."— Vizcaya Museum & Gardens[39]

Vizcaya was built with a residential elevator, but it is closed to the public. Vizcaya does not meet ADA standards.[8]

In popular culture

Vizcaya has provided the setting for many films, both credited and uncredited. Deering himself enjoyed watching silent films in Vizcaya's courtyard, and he had a particular interest in the works of Charlie Chaplin. External pictures of Vizcaya can be seen in the films Tony Rome, Ace Ventura: Pet Detective,[40][41] Any Given Sunday,[42] Bad Boys II, Airport '77, Haunts of the Very Rich, The Money Pit, The Champ, This Thing is Ours, Dostana,[43] Daring Game[44] and Iron Man 3. The music video for The Cover Girls' 1988 song "Promise Me" was filmed at Vizcaya,[45] as were the music videos for New Edition's "I'm Still In Love With You" and Cristian Castro's song Si Tú Me Amaras from 1997. Vizcaya was often used as the setting for the South Florida filming of the wedding reality show Four Weddings.[46] The daytime soap opera Days of Our Lives also had scenes filmed at Vizcaya.[44]

The estate can be seen in the background of various photographs taken by photographer Bunny Yeager of model Bettie Page during their working relationship in the 1950s.[47]

Vizcaya is also an extremely popular location for weddings and other special events, given the site's architectural and natural beauty. For decades, the estate has been a subject of photography, and is a favored site for photographs of women celebrating their quinceañera (15th birthday).[48]

On April 18, 2012, the AIA's Florida Chapter placed Vizcaya on its list of Florida Architecture: 100 Years. 100 Places.[49]

Gallery

Estate Entrance at S. Miami Ave.

Estate Entrance at S. Miami Ave. Vizcaya: Entrance drive view of north Villa facade

Vizcaya: Entrance drive view of north Villa facade West view of Villa from the Italian Renaissance gardens.

West view of Villa from the Italian Renaissance gardens.

Caravel suspended from the ceiling at Vizcaya

Caravel suspended from the ceiling at Vizcaya Spiral staircase inside the house at Vizcaya Museum and Gardens

Spiral staircase inside the house at Vizcaya Museum and Gardens Living Room Organ at Vizcaya Museum & Gardens

Living Room Organ at Vizcaya Museum & Gardens

See also

References

Notes

- 1 2 3 "Dade County listings". Florida's History Through Its Places. Florida's Office of Cultural and Historical Programs. February 20, 2007. Archived from the original on September 27, 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 "Vizcaya". National Historic Landmark summary listing. National Park Service. Archived from the original on December 2, 2007. Retrieved June 21, 2008.

- ↑ "National Register of Historic Places Inventory-Nomination". National Park Service. October 1993.

- 1 2 "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. July 9, 2010.

- ↑ "Francis Burrall Hoffman, Jr., the Architect". Vizcaya Museum and Gardens. Retrieved October 7, 2019.

- ↑ Dubrow, Gail (2021). "Practicing Architecture Under the Bamboo Ceiling: The Life and Work of Iwahiko Tsumanuma (Thomas S. Rockrise), 1878-1936". Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians. 80 (3): 280–303.

- ↑ "Diego Suarez, the Landscape Architect". Vizcaya Museum and Gardens. Retrieved October 7, 2019.

- 1 2 3 Scheckner, Jesse (September 1, 2020). "Accessibility to historic Vizcaya under microscope". Miami Today. Retrieved June 21, 2021.

The floors of the estate, built nearly a century ago, were uneven in places. Many parts of the grounds both inside and in the gardens outside couldn't be accessed by wheelchair....We were told there was no elevator for them to get to the second floor of the house...The museum has two wheelchair lifts to help visitors gain access to the grounds from the parking lot. One works, though Vizcaya temporarily removed its four on-site wheelchairs in May to reduce touchpoints during the pandemic. The other still awaits repairs for damages sustained during Hurricane Irma in 2017....Miami-Dade in 2017 entered into a long-term operating and management agreement with Vizcaya Museum and Gardens Trust Inc., a local nonprofit. The county still provides funds for "upkeep, maintenance, renovations and operations … in the form of annual budget appropriations and grants," Mr. Martinez's item said.

- ↑ "Life at Vizcaya". Vizcaya Museum & Gardens. 2018.

- ↑ Bartle, Annette (1989). "Vizcaya retains touch of the Renaissance". Doylestown Intelligencer (April 2, 1989). Retrieved September 2, 2018.

- ↑ Federal Writers' Project (1939), Florida. A Guide to the Southernmost State, New York: Oxford University Press, p. 168

- ↑ "Miami-Dade County - Timeline". August 23, 2015. Archived from the original on August 23, 2015.

- ↑ "Paul Chalfin, the Artistic Director". vizcaya.org. Archived from the original on May 12, 2015. Retrieved June 21, 2021.

- ↑ "Francis Burrall Hoffman, Jr., the Architect". vizcaya.org. Archived from the original on April 18, 2015. Retrieved June 21, 2021.

- ↑ "Miami-Dade County - Timeline". August 23, 2015. Archived from the original on August 23, 2015.

- ↑ "Diego Suarez, the Landscape Architect". vizcaya.org. Archived from the original on June 27, 2015. Retrieved June 21, 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Vizcaya's History Archived April 12, 2010, at the Wayback Machine, Vizcaya Museum & Gardens official site

- ↑ "Vizcaya Museum & Gardens - House Overview". July 30, 2015. Archived from the original on July 30, 2015.

- ↑ Bosch, Richard. "Villa Rezzonico at Bassano del Grappa (VI)". Richard Bosch Architect. Retrieved June 21, 2021.

- ↑ Vizcaya: An American Villa and Its Makers by Witold Rybczynski, Laurie Olin, Steven Brooke

- ↑ The American Country House by Clive Aslet

- ↑ Historic Preservation: Quarterly of the National Council for Historic Sites by National Council for Historic Sites and Buildings, National Trust for Historic Preservation in the United States]

- ↑ The Vizcaya Museum and Gardens, Frommer's

- 1 2 Historical Traveler's Guide to Florida by Eliot Kleinberg

- ↑ "Vizcaya". Flashback Miami. October 22, 2014. Retrieved June 28, 2016.

- ↑ "Trio Arrested with Silver in New York". Spokane Daily Chronicle. March 25, 1971. Retrieved June 21, 2017.

- ↑ "Big cache of art, jewelry; trio arrested". The Bryan Times. March 25, 1971. Retrieved June 21, 2017.

- 1 2 11 Most Endangered - Vizcaya and Bonnet House Archived June 30, 2008, at the Wayback Machine, PreservationNation - National Trust for Historic Preservation

- ↑ "vizcaya museum and gardens".

- ↑ "Inside Vizcaya Museums & Gardens in Miami". Human Research. March 14, 2019. Retrieved March 14, 2019.

- ↑ "Roses Return After 100 Years - Vizcaya".

- ↑ Buch, Clarissa. "Vizcaya Restores Iconic Swimming Pool Grotto and Rare Mural by Robert Winthrop Chanler". Miami New Times.

- ↑ "Finding Solutions - Vizcaya". November 13, 2019.

- ↑ Barrett, Devlin (May 21, 2008). "Threats to history seen in budget cuts, bulldozers". Yahoo! News. Archived from the original on June 3, 2008. Retrieved June 21, 2008.

- ↑ "Plan your next trip with the National Trust | National Trust for Historic Preservation". Archived from the original on June 30, 2008. Retrieved June 21, 2008.

- ↑ "Baynanza". www.miamidade.gov. Archived from the original on April 18, 2021. Retrieved April 13, 2020.

- ↑ "Ronald Reagan Presidential Library, National Archives and Records Administration". www.reagan.utexas.edu. Archived from the original on March 8, 2016. Retrieved June 21, 2017.

- ↑ Florida Fun Facts by Eliot Kleinberg

- ↑ "House Overview". Vizcaya Museum & Gardens. Archived from the original on July 30, 2015. Retrieved June 21, 2021.

- ↑ Ace Ventura: Pet Detective

- ↑ "Ace Ventura - Pet Detective filming locations". Archived from the original on January 31, 2010. Retrieved June 21, 2008.

- ↑ "Any Given Sunday (1999) - IMDb" – via www.imdb.com.

- ↑ "Friendship (2008) - IMDb". IMDb.

- 1 2 "Filming Location Matching "Villa Vizcaya - 3251 S. Miami Avenue, Miami, Florida, USA" (Sorted by Popularity Ascending)". IMDb.

- ↑ The Cover Girls song "Promise Me" at YouTube

- ↑ Sentinel, Rod Stafford Hagwood, Sun. "TLC's "Four Weddings" features Fort Lauderdale brides". Sun-Sentinel.com.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Bettie Page: Queen of Curves (2014) Petra Mason (Author), Bunny Yeager (Foreword)ISBN 9780789327482

- ↑ "Vizcaya Seeks Quinceañera Photos Through the Years". NBC 6 South Florida. Retrieved June 22, 2017.

- ↑ "Start Voting for Your Favorite Florida Architecture!". 2021 People's Choice Award (Florida Architecture).

Bibliography

- Griswold, Mac and Weller, Eleanor (1991) The Golden Age of American Gardens, proud owners-private estates 1890 - 1940 New YorkL Harry N. Abrahms. ISBN 0-8109-2737-3

- A comprehensive account

- Harwood, Kathryn C. (1985) Lives of Vizcaya. Banyan Books, Miami.

- Maher, James T. (1975) Twilight of Splendor: Chronicles of the Age of American Palaces. Boston: Little, Brown.

- A comprehensive account.

- Ossman, Laurie (text) and Sumner, Bill (photographs) (1985_ Visions of Vizcaya. Vizcaya Museum and Gardens/Miami-Dade County, Miami.

- Rybczynski, Witold and Olin, Laurie (text); Brooke, Steven (photographer) (2006) Vizcaya: An American Villa and Its Makers Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press

- In depth study of villa, gardens, and the creative team.