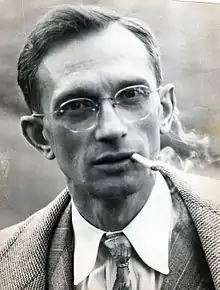

Vladimir Petrov | |

|---|---|

| |

| Native name | Владимир Николаевич Петров |

| Born | Vladimir Nikolayevich Petrov 1915 Ekaterinodar oblast, Russian Empire |

| Died | 1999 Kensington, Maryland, US |

| Occupation | Writer, political dissident, factory worker, academic |

| Language | Russian |

| Citizenship | Russian Empire Soviet Union United States |

| Subject | Politics |

| Notable works | Escape from the Future |

Vladimir Nikolayevich Petrov (1915 in Ekaterinodar oblast, Russian Empire – March 17, 1999 in Kensington, Maryland) was at various times an academic, philatelist, prisoner, forced laborer, political prisoner, adventurer, factory worker, chess player and writer of short stories and autobiographies. He was at various times a Russian, American, and man of no country, though he was brought up in the USSR and died in the United States. Most of the information concerning his life originates from his personal memoirs, entitled Soviet Gold and My Retreat from Russia and collected in the published work Escape from the Future.

Early life

Petrov was born in Russia in 1915 during the last days of the Tsar. His parents were from the petit bourgeoisie, his mother a teacher in an experimental school, his father a free-thinker, banker and lay philosopher (follower of Ernest Renan, among others). His father was part of a group socially-minded associates who organized a farmer's credit union, thus enabling farmers to own their means of production during the early years of socialism. The success of the farmers' bank (in its heyday the farmers collectively owned several trucks and even a river steamship for transporting their produce directly to city markets) brought trouble from the Bolshevik authorities. Petrov's father was imprisoned for the first time when young Volodya was 7 years old, for allegedly exploiting the working classes. Upon his release, Petrov's father called him up to Leningrad to continue his studies at a technical high school. Petrov was 14 and wished to study history, but his father's prison record excluded his son from this potentially political subject. Petrov later entered the department of civil engineering at the University of Leningrad, living in his words "the meager existence of a young student" [1] where he was arrested on the night of February 17, 1935 by the NKVD.[2] He was arrested at age 19 as part of the mass purges which followed in the wake of the assassination of Sergey Kirov.[3] He was imprisoned and tortured for months before being formally charged with a crime.

Petrov's namesake son summarizes the reason for his father's arrest as "for coming to the defense of a rape victim."

The crimes he was charged with were, as related in his autobiography:

1. Writing of anti-soviet character (my diaries).

2. Possession of counter-revolutionary literature (the diaries...)

3. Espionage (correspondence with philatelists in the United States of America and Yugoslavia)

4. Anti-Soviet propaganda abroad (ditto).

5. Fomenting an armed uprising among the Cossacks...

6. Preparations for robbing savings banks and co-operatives...

7. Organization of counter-revolutionary group among the student of my institute...

8. Anti-Soviet propaganda among the population[4]

An NKVD Troika convicted him of charges 1, 5, and 7 as given above. The only evidence presented was a personal diary he had written when he was 16. Without being able to consult counsel or view the evidence against him, he was sentenced to six years hard labor in the gold fields of the Kolyma.[5] Due to their association with him, multiple of his colleagues were arrested on similar charges of counter-revolutionary activity.

He was sentenced under Article 58, Paragraphs 10 and 14 of the Soviet legal code. This made him a "contra" or "counter-revolutionary political prisoner," a resident of the Gulag archipelago.[6]

Prison term

During his internment, Petrov's life was one of complex vacillations. He at times had more freedom than many prisoners, including freedom of movement, sufficient food, medical care, private housing, and female companionship. At times he was one of the worst-treated of all prisoners in the GULAG system, living on a bread ration of less than half a kilogram per day and working near-naked in sub-zero waters to mine gold for the NKVD.[7] He constantly lived in hope of having his sentence commuted, and constantly lived in fear of Serpantinnaya, a 'truck stop' north of Magadan which Petrov charges was used by the NKVD to perform summary executions.[8]

He attempted escape numerous times,[9] some of which attempts were only routed based upon lack of provisions and protective clothing to combat the Russian Winter. He traded in camp vodka and performed electrical repairs for fees and favors. He liaised with the wives of camp leaders. He became exposed to political dissidence, meeting Trotskyites, anarchists, as well as doctrinaire Bolsheviks and informants for the Cheka.[10] During his term he also discovered the largest ever gold nugget in the history of the Kolyma gold fields. He was severely wounded by ammonal explosions in a mine, he was often beaten by guards and interrogators, and many times he existed on starvation rations for extended periods of time.[11]

Petrov's earthy wit, chess skills and relative youth were keys to his survival of Kolyma. He became friends with many people during his prison term. Among them was a red-haired man known as Prostoserdov, a Menshevik and vocal opponent of Stalinism. It is assumed that Prostoserdov's execution would have made him a martyr; as a result, he was among the most elect prisoners in terms of treatment and privileges. Petrov's run-ins with Prostoserdov serve as one of the work's most poignant refrain; each encounter shows how each man has changed, and how they have struggled to remain themselves.

Once, by his own admission, he murdered a cruel camp official in cold blood using a pickaxe.[12] On many other occasions he conspired with fellow prisoners or in other ways violated the rules of Dalstroy. Sometimes he was placed on a lower bread ration, but rarely as a direct result of his actual transgressions. He was never severely punished, nor was his prison term lengthened.[13] He at times went on hunger strikes to protest camp conditions, though he like other prisoners, was chronically mal-nourished and afflicted by scurvy.

It has been claimed that much of his account bears similarities to the later semi-fictional account of Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn in One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich.[14] It has also been compared to Papillon by Henri Charrière. It is possible that Petrov's internment overlapped with that of Varlam Shalamov, the Russian writer, whose Kolyma Tales depict the brutality of human nature laid bare in this remote camp of the archipelago.

After prison

Released from prison in the week that Nazi Germany invaded the USSR in World War II, Petrov made his way across Russia on the Trans-Siberian Railroad. He avoided Soviet mobilization; as an ex-convict he would have been placed in a mine-clearing battalion. The German front established by Operation Barbarossa passed by his town and thus came under control of the Third Reich. He managed, over two years, to work his way across Eastern Europe, into Germany and then Italy. In Nazi Germany, he contacted and played a role in the anti-stalinist operations of General Andrey Vlasov.

His memoirs give markedly less information concerning his association with Vlasov than they do about almost all his other associations, even those with minor convicts. This has fueled speculation as to how he managed to secure passage to America at the end of the war.

After the war

In 1947 he managed to secure transportation to America through the good offices of the Tolstoy Foundation, an organization that helped numerous Russians reach the US. Here, after a stint as a factory-worker, he became an academic and taught at such schools as Yale University and George Washington University while raising a family. In 1955 and 1956 Petrov worked at Radio Liberty in Munich. Prof. Petrov's academic works included the books 'Money and Conquest', 'A Study in Diplomacy', 'What China Policy?', 'June 22, 1941' as well as various academic monographs. His later work in Sino-Soviet affairs led him to study the controversial relationship between Joseph Stalin and Mao Zedong, and to openly question American foreign policy regarding what he considered to be an absurd non-recognition of China. True to his childhood passion for history, he was averse to all forms of historical re-writing, and his academic approach could be described as journalistic, as he much preferred eyewitness interviews to second-hand accounts.

In the 1950s Petrov participated in emigre politics and was a regular contributor to the newspaper Novoye Russkoye Slovo under a pseudonym. His connections included people as diverse as Alexander Kerensky and Max Eastman. He published the first volume of his memoirs, Soviet Gold, in 1949, and My Retreat from Russia a couple of years later. Soviet Gold was the first published memoir of a Gulag prisoner in the West, and received a favorable review from Winston Churchill. In 1947, he and Henry A. Wallace met, and Wallace publicly apologized for having misrepresented reality when he visited Magadan in 1944.[15] During the McCarthy trials Petrov was called upon to describe the conditions in the Soviet concentration camps. Petrov was published by William I Nichols, editor of the popular This Week syndicated magazine. Nichols published excerpts of Petrov's memoirs and encouraged the publication of his humorous short stories, fondly calling Petrov "a poor-man's Tchekov".

Vladimir Petrov died March 17, 1999 at age 83 at his home in Kensington, Maryland, after a brief illness. Among those who doted upon him during those last months was daughter-in-law Patty who had only recently married Vladimir, Jr. but very quickly came to "adore" and form a close bond with the elder Petrov. He was survived by his wife, Jean MacNab, nine children—George, Susie, Lili, Vlad, Sasha, Jane, Anne, Andre and Carol—and seven grandchildren, many of whom work in science, technology, medicine, and the arts. "Live for today, never mind tomorrow", was one of his favorite sayings.

See also

References

- ↑ Soviet Gold, "Prisons of the City of Lenin" (p. 15)

- ↑ Soviet Gold, "The Big House" (p. 31)

- ↑ Soviet Gold, "Prisons of the City of Lenin" (p. 31)

- ↑ Soviet Gold, "Prisons of the City of Lenin" (p. 63)

- ↑ Soviet Gold, "Prisons of the City of Lenin" (p. 67)

- ↑ Soviet Gold, "Prisons of the City of Lenin" (p. 71)

- ↑ Soviet Gold, "At The Bottom" (p.225)

- ↑ Soviet Gold, "Black Times" (p.195)

- ↑ Soviet Gold, "On The Way To Freedom" (p.250)

- ↑ Soviet Gold, "Magadan: Capital of the Kolyma" (p. 108)

- ↑ Soviet Gold, "Hard Time" (p. 225)

- ↑ Soviet Gold, "Black Times" (p. 196)

- ↑ Soviet Gold, general

- ↑ Soviet Gold, "Introduction" (p. vi)

- ↑ Tim Tzouliadis (2008). The Forsaken. The Penguin Press. p. 280. ISBN 978-1-59420-168-4.

Sources

- Petrov, Vladimir (1949). Soviet Gold, Farrar Straus, New York.

- Petrov, Vladimir (1950). My Retreat from Russia, Yale University Press, New Haven

- Petrov, Vladimir (1973). Escape from the Future: The Incredible Adventures of a Young Russian, Indiana University Press, Bloomington, ISBN 025320190X.

Note: Escape from the Future is a single-volume combination of the stories Soviet Gold and My Retreat from Russia. Apart from a short preface, it contains no new material.