| Vredefort impact structure | |

|---|---|

| Vredefort Dome | |

Vredefort Dome (centre), with the Vaal river running across it; seen from space with the Operational Land Imager on Landsat 8, 27 June 2018 | |

| Impact crater/structure | |

| Confidence | Confirmed |

| Diameter | 170–300 km (110–190 mi) (estimated former crater diameter) |

| Age | ± 4 Ma Orosirian, Paleoproterozoic |

| Exposed | Yes |

| Drilled | Yes |

| Location | |

| Coordinates | 27°0′0″S 27°30′0″E / 27.00000°S 27.50000°E |

| Country | South Africa |

| Province | Free State |

Location of Vredefort impact structure | |

| Official name | Vredefort Dome |

| Includes |

|

| Criteria | Natural: (viii) |

| Reference | 1162 |

| Inscription | 2005 (29th Session) |

| Area | 30,000 ha (120 sq mi) |

The Vredefort impact structure is one of the largest verified impact structures on Earth.[1] The crater, which has since been eroded away, has been estimated at 170–300 kilometres (110–190 mi) across when it was formed.[2][3] The remaining structure, comprising the deformed underlying bedrock, is located in present-day Free State province of South Africa. It is named after the town of Vredefort, which is near its centre. The structure's central uplift is known as the Vredefort Dome. The impact structure was formed during the Paleoproterozoic Era, 2.023 billion (± 4 million) years ago. It is the second-oldest known impact structure on Earth, after Yarrabubba.

In 2005, the Vredefort Dome was added to the list of UNESCO World Heritage Sites for its geologic interest.

Formation and structure

The asteroid that hit Vredefort is estimated to have been one of the largest ever to strike Earth since the Hadean Eon some four billion years ago, originally thought to have been approximately 10–15 km (6.2–9.3 mi) in diameter.[4] As of 2022, the bolide was estimated at between 20 and 25 kilometres (12 and 16 mi) in diameter and to have impacted with a vertical velocity of 15–25 kilometres per second (34,000–56,000 mph).[3]

The original impact structure is estimated to have had a diameter of at least 170 km (110 mi), with the impact affecting the structure of the surrounding host rock in a circular region around 300 km (190 mi) in diameter.[2] Other estimates have placed the original crater diameter closer to 300 km (190 mi).[3] The landscape has since been eroded to a depth of around 7–11 km (4.3–6.8 mi) since formation, obliterating the original crater. The remaining structure, the "Vredefort Dome", consists of a partial ring of hills 70 km (43 mi) in diameter, and is the remains of the central uplift created by the rebound of rock below the impact site after the collision.[2]

Estimates have placed the structure’s age to be 2.023 billion years (± 4 million years)[5] or 2.019/2.020 billion years (± 2-3 million years) old.[6] which places it in the Orosirian Period of the Paleoproterozoic Era. It is the second oldest universally accepted impact structure on Earth. In comparison, it is about 10% older than the Sudbury Basin impact (at 1.849 billion years) and the Yarrabubba impact structure is older than the Vredefort impact structure by about 0.2 billion years.[7] Other purported older impact structures have either poorly constrained ages (Dhala impact structure, India)[8] or highly contentious impact evidence in case of the circa 3.023 billion year old Maniitsoq structure, West Greenland[9] and the circa 2.4 billion year old Suavjärvi structure, Russia.[10] Their classification as impact structures remain controversial and unsettled.[7][11]

The dome in the centre of the impact structure was originally thought to have been formed by a volcanic explosion, but in the mid-1990s, evidence revealed it was the site of a huge bolide impact, as telltale shatter cones were discovered in the bed of the nearby Vaal River.

This impact structure is one of the few multiple-ringed impact structures on Earth, although they are more common elsewhere in the Solar System. Perhaps the best-known example is Valhalla crater on Jupiter's moon Callisto. Earth's Moon has some as well. Geological processes, such as erosion and plate tectonics, have destroyed most multiple-ring impact structures on Earth.

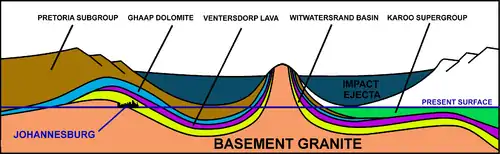

The impact distorted the Witwatersrand Basin which was laid down over a period of 250 million years between 950 and 700 million years before the Vredefort impact. The overlying Ventersdorp lavas and the Transvaal Supergroup which were laid down between 700 and 80 million years before the meteorite strike, were similarly distorted by the formation of the 300-kilometre-wide (190 mi) impact structure.[4][12] The rocks form partial concentric rings around the impact structure's centre today, with the oldest, the Witwatersrand rocks, forming a semicircle 25 km (16 mi) from the centre. Since the Witwatersrand rocks consist of several layers of very hard, erosion-resistant sediments (e.g. quartzites and banded ironstones),[4][13] they form the prominent arc of hills that can be seen to the northwest of the impact structure's centre in the satellite picture above. The Witwatersrand rocks are followed, in succession, by the Ventersdorp lavas at a distance of about 35 km (22 mi) from the centre, and the Transvaal Supergroup, consisting of a narrow band of the Ghaap Dolomite rocks and the Pretoria Subgroup of rocks, which together form a 25-to-30-kilometre-wide (16 to 19 mi) band beyond that.[14]

From about halfway through the Pretoria Subgroup of rocks around the impact structure's centre, the order of the rocks is reversed. Moving outwards towards where the crater rim used to be, the Ghaap Dolomite group resurfaces at 60 km (37 mi) from the centre, followed by an arc of Ventersdorp lavas, beyond which, at between 80 and 120 km (50 and 75 mi) from the centre, the Witwatersrand rocks re-emerge to form an interrupted arc of outcrops today. The Johannesburg group is the most famous one because it was here that gold was discovered in 1886.[4][14] It is thus possible that if it had not been for the Vredefort impact this gold would never have been discovered.[4]

The 40-kilometre-diameter (25 mi) centre of the Vredefort impact structure consists of a granite dome (where it is not covered by much younger rocks belonging to the Karoo Supergroup) which is an exposed part of the Kaapvaal craton, one of the oldest microcontinents which formed on Earth 3.9 billion years ago.[4] This central peak uplift, or dome, is typical of a complex impact structure, where the liquefied rocks splashed up in the wake of the meteor as it penetrated the surface.

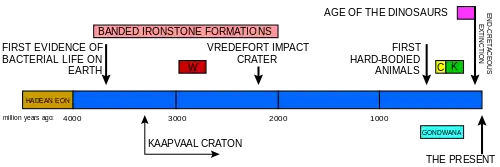

A timeline of the Earth's history indicating when the Vredefort impact structure was formed in relation to some of the other important South African geological events. W indicates when the Witwatersrand Supergroup was laid down, C the Cape Supergroup, and K the Karoo Supergroup. The graph also indicates the period during which banded ironstone formations were formed on earth, indicative of an oxygen-free atmosphere. The Earth's crust was wholly or partially molten during the Hadean Eon. One of the first microcontinents to form was the Kaapvaal Craton, which is exposed at the centre of the Vredefort Dome, and again north of Johannesburg.

A timeline of the Earth's history indicating when the Vredefort impact structure was formed in relation to some of the other important South African geological events. W indicates when the Witwatersrand Supergroup was laid down, C the Cape Supergroup, and K the Karoo Supergroup. The graph also indicates the period during which banded ironstone formations were formed on earth, indicative of an oxygen-free atmosphere. The Earth's crust was wholly or partially molten during the Hadean Eon. One of the first microcontinents to form was the Kaapvaal Craton, which is exposed at the centre of the Vredefort Dome, and again north of Johannesburg. A schematic diagram of a NE (left) to SW (right) cross-section through the 2.020-billion-year-old Vredefort impact structure and how it distorted the contemporary geological structures. The present erosion level is shown. Johannesburg is where the Witwatersrand Basin (the yellow layer) is exposed at the "present surface" line, just inside the impact structure's rim, on the left. Not to scale.

A schematic diagram of a NE (left) to SW (right) cross-section through the 2.020-billion-year-old Vredefort impact structure and how it distorted the contemporary geological structures. The present erosion level is shown. Johannesburg is where the Witwatersrand Basin (the yellow layer) is exposed at the "present surface" line, just inside the impact structure's rim, on the left. Not to scale.

Conservation

The Vredefort Dome World Heritage Site is currently subject to property development, and local owners have expressed concern regarding sewage dumping into the Vaal River and the impact structure.[15] The granting of prospecting rights around the edges of the impact structure has led environmental interests to express fear of destructive mining.

Community

The Vredefort Dome in the centre of the impact structure is home to four towns: Parys, Vredefort, Koppies and Venterskroon. Parys is the largest and a tourist hub; both Vredefort and Koppies mainly depend on an agricultural economy.

On 19 December 2011, a broadcasting licence was granted by ICASA to a community radio station to broadcast for the Afrikaans- and English-speaking members of the communities within the impact structure. The Afrikaans name Koepel Stereo (Dome Stereo) refers to the dome and announces its broadcast as KSFM. The station broadcasts on 94.9 MHz FM.

See also

References

- ↑ University of Rochester (26 September 2022). "The asteroid that formed Vredefort crater was bigger than previously believed". Science X. Archived from the original on 26 September 2022.

- 1 2 3 Huber, M. S.; Kovaleva, E.; Rae, A. S. P.; Tisato, N.; Gulick, S. P. S. (August 2023). "Can Archean Impact Structures Be Discovered? A Case Study From Earth's Largest, Most Deeply Eroded Impact Structure". Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets. 128 (8). doi:10.1029/2022JE007721. ISSN 2169-9097.

- 1 2 3 Allen, Natalie H.; Nakajima, Miki; Wünnemann, Kai; Helhoski, Søren; Trail, Dustin (2022). "A Revision of the Formation Conditions of the Vredefort Crater". Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets. 127 (8): e2022JE007186. Bibcode:2022JGRE..12707186A. doi:10.1029/2022JE007186. S2CID 251449730.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 McCarthy, Terence (2005). The Story of Earth & Life. Struik Publishers. pp. 89–90, 102–107, 134–136. ISBN 978-1-77007-148-3. OCLC 883592852.

- ↑ Kamo, S.L.; Reimold, W.U.; Krogh, T.E.; Colliston, W.P. (November 1996). "A 2.023 Ga age for the Vredefort impact event and a first report of shock metamorphosed zircons in pseudotachylitic breccias and Granophyre". Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 144 (3–4): 369–387. doi:10.1016/S0012-821X(96)00180-X.

- ↑ Moser, D. E. (1997). "Dating the shock wave and thermal imprint of the giant Vredefort impact, South Africa". Geology. 25 (1): 7. doi:10.1130/0091-7613(1997)025<0007:DTSWAT>2.3.CO;2. ISSN 0091-7613.

- 1 2 Erickson, T.M., Kirkland, C.L., Timms, N.E., Cavosie, A.J. and Davison, T.M., 2020. Precise radiometric age establishes Yarrabubba, Western Australia, as Earth’s oldest recognised meteorite impact structure. Nature communications, 11(1), pp.1-8. doi:10.1038/s41467-019-13985-7

- ↑ Pati, J.K., Qu, W.J., Koeberl, C., Reimold, W.U., Chakarvorty, M. and Schmitt, R.T., 2017. Geochemical evidence of an extraterrestrial component in impact melt breccia from the Paleoproterozoic Dhala impact structure, India. Meteoritics & Planetary Science, 52(4), pp.722-736. doi:10.1111/maps.12826

- ↑ Garde, A.A., McDonald, I., Dyck, B. and Keulen, N., 2012. Searching for giant, ancient impact structures on Earth: the Mesoarchaean Maniitsoq structure, West Greenland. Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 337, pp.197-210. doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2012.04.026

- ↑ Mashchak, M.S. and Naumov, M.V., 2012. The Suavjärvi impact structure, NW Russia. Meteoritics & Planetary Science, 47(10), pp.1644-1658. doi:10.1111/j.1945-5100.2012.01428.x

- ↑ Reimold, W.U.; Ferrière, L.; Deutsch, A.; Koeberl, C. (2014). "Impact controversies: impact recognition criteria and related issues". Meteoritics & Planetary Science. 49 (5): 723–731. Bibcode:2014M&PS...49..723R. doi:10.1111/maps.12284. Retrieved 12 October 2023.

- ↑ Norman, Nick; Whitfield, Gavin (2006). Geological Journeys. Struik Publishers. pp. 38–49, 60–61. ISBN 978-1-77007-062-2. OCLC 974035410.

- ↑ Truswell, J. F (1977). The Geological Evolution of South Africa. Purnell. pp. 23–38. OCLC 488347575.

- 1 2 Geological map of South Africa, Lesotho and Swaziland (1970). Council for Geoscience, Geological Survey of South Africa.

- ↑ Momberg, Eleanor (23 August 2009). "River heading for the rocks". Retrieved 22 March 2011.

External links

- Parys South Africa

- Impact Cratering Research Group – University of the Witwatersrand

- Earth Impact Database

- Deep Impact – The Vredefort Dome

- Satellite image of Vredefort impact structure from Google Maps

- Impact Cratering: an overview of Mineralogical and Geochemical aspects – University of Vienna Archived 2011-07-06 at the Wayback Machine

- Google Earth 3d .KMZ of 25 largest craters (requires Google Earth)