| Wag the Dog | |

|---|---|

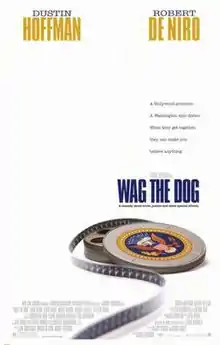

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Barry Levinson |

| Screenplay by | |

| Based on | American Hero by Larry Beinhart |

| Produced by |

|

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Robert Richardson |

| Edited by | Stu Linder |

| Music by | Mark Knopfler |

Production companies |

|

| Distributed by | New Line Cinema |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 97 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $15 million[1] |

| Box office | $64.3 million[2] |

Wag the Dog is a 1997 American political satire black comedy film produced and directed by Barry Levinson and starring Dustin Hoffman and Robert De Niro.[1] The film centers on a spin doctor and a Hollywood producer who fabricate a war in Albania to distract voters from a presidential sex scandal. The screenplay by Hilary Henkin and David Mamet was loosely adapted from Larry Beinhart's 1993 novel, American Hero.

Wag the Dog was released one month before the news broke of the Clinton–Lewinsky scandal and the bombing of the Al-Shifa pharmaceutical factory in Sudan by the Clinton administration in August 1998, which prompted the media to draw comparisons between the film and reality.[3] The comparison was also made in December 1998, when the administration initiated a bombing campaign of Iraq during Clinton's impeachment trial for the Clinton–Lewinsky scandal.[4] It was made again in spring 1999, when the administration intervened in the Kosovo War and initiated a bombing campaign against Yugoslavia, which, coincidentally, bordered Albania and contained ethnic Albanians.[5] The film grossed $64.3 million on a $15 million budget, and was well received by critics, who praised the direction, performances, themes and humor. Hoffman received a nomination for the Academy Award for Best Actor for his performance, and screenwriters David Mamet and Hilary Henkin were both nominated for Best Adapted Screenplay.

Plot

The president is caught making advances on an underage girl inside the Oval Office, less than two weeks before the election. Conrad Brean, a top spin doctor, is brought in by presidential aide Winifred Ames to take the public's attention away from the scandal. He decides to construct a fictional war in Albania, hoping the media will concentrate on this instead. Brean contacts Hollywood producer Stanley Motss to create the war, complete with a theme song and fake film footage of a fleeing orphan to arouse sympathy. The hoax is initially successful, with the president quickly gaining ground in the polls.

When the CIA learns of the plot, they send Agent Young to confront Brean about the hoax. Brean convinces Young that revealing the deception is against his and the CIA's best interests. But when the CIA — in collusion with the president's rival candidate — reports that the war has ended, the media begins to focus back on the president's sexual abuse scandal. To counter this, Motss invents a hero who was left behind enemy lines in Albania.

Inspired by the idea that he was "discarded like an old shoe", Brean and Motss ask the Pentagon to provide a special forces soldier with a matching name (a sergeant named "Schumann" is identified), around whom a POW narrative can be constructed. As part of the hoax, folk singer Johnny Dean records a song called "Old Shoe", which is pressed onto a 78 rpm record, prematurely aged so that listeners will think it was recorded years earlier, and sent to the Library of Congress to be "found". Soon, large numbers of old pairs of shoes begin appearing on phone and power lines, and a grassroots movement takes hold.

When the team goes to retrieve Schumann, they discover he is in fact a criminally insane Army convict. On the way back, their plane crashes en route to Andrews Air Force Base. The team survives and is rescued by a farmer, an illegal alien who is given expedited citizenship for a better story. However, Schumann is killed when he attempts to rape a gas station owner's daughter. Seizing the opportunity, Motss stages an elaborate military funeral for Schumann, claiming he died from wounds sustained during his rescue.

While watching a political talk show, Motss gets frustrated that the media are crediting the president's upsurge in the polls to the bland campaign slogan of "Don't change horses in mid-stream" rather than to Motss's hard work. Motss states he wants credit and will reveal his involvement, despite Brean's offer of an ambassadorship and the dire warning that he is "playing with his life". After Motss refuses to change his mind, Brean reluctantly orders his security staff to kill him. A newscast reports that Motss has died of a heart attack at home, the president has been successfully re-elected, and an Albanian terrorist organization has claimed responsibility for a recent bombing, suggesting the fake war is prompting a real one.

Cast

- Robert De Niro as Conrad Brean

- Dustin Hoffman as Stanley Motss

- Anne Heche as Winifred Ames

- Denis Leary as 'Fad King'

- Willie Nelson as Johnny Dean

- Andrea Martin as Liz Butsky

- Kirsten Dunst as Tracy Lime

- William H. Macy as CIA Agent Charles Young

- Craig T. Nelson as Senator Neal

- George Gaynes as Senator Cole

- John Michael Higgins as John Levy

- Sean Masterson as Bob Richardson

- Suzie Plakson as Grace

- Woody Harrelson as Sergeant William Schumann

- Suzanne Cryer as Amy Cain

- James Belushi as himself

- Shirley Prestia as herself

- Roebuck "Pops" Staples as himself

- Merle Haggard as himself

Production

Title

The title of the film comes from the idiomatic English-language expression, "the tail wagging the dog",[6] which is referenced at the beginning of the film by a caption that reads:

Why does the dog wag its tail?

Because a dog is smarter than its tail.

If the tail were smarter, it would wag the dog.

Motss and Evans

Hoffman's character, Stanley Motss, is said to have been based directly on famed producer Robert Evans. Similarities have been noted between the character and Evans's work habits, mannerisms, quirks, clothing style, hairstyle and large, square-framed eyeglasses. In fact, the real Evans is said to have joked, "I'm magnificent in this film".[7]

Hoffman has never discussed deriving inspiration from Evans. He may have provided for the role, as claimed on the commentary track for the film's DVD release, but much of Motss's characterization was based on Hoffman's father, Harry Hoffman, a former prop manager for Columbia Pictures.

Writing credits

The writing of credits on the film became controversial at the time, due to objections by Barry Levinson. After Levinson became attached as director, David Mamet was hired to rewrite Hilary Henkin's screenplay, which was loosely adapted from Larry Beinhart's novel, American Hero.

Given the close relationship between Levinson and Mamet, New Line Cinema asked that Mamet be given sole credit for the screenplay. However, the Writers Guild of America intervened on Henkin's behalf to ensure that Henkin received first-position shared screenplay credit, finding that, as the original screenwriter, Henkin had created the screenplay's structure, as well as much of the screen story and dialogue.[8]

Levinson threatened to quit the Guild (but he did not), claiming that Mamet had written all of the dialogue, as well as creating the characters of Motss and Schumann, and had originated most of the scenes set in Hollywood, and all of the scenes set in Nashville. Levinson attributed the numerous similarities between Henkin's original version and the eventual shooting script to Henkin and Mamet working from the same novel, but the Writers Guild of America disagreed in its credit arbitration ruling.[9]

Music

The film features many songs created for the fictitious campaign waged by the protagonists. These songs include "Good Old Shoe", "The American Dream" and "The Men of the 303". However, none of these pieces made it onto the soundtrack album. The CD featured only the title track (by British guitarist and vocalist Mark Knopfler) and seven of Knopfler's instrumentals.

Songs as listed in the film's credits

- "Thank Heaven for Little Girls": written by Lerner and Lowe, performed by Maurice Chevalier

- "I Guard the Canadian Border": written by Tom Bähler and Willie Nelson, performed by Willie Nelson

- "The American Dream": written by Bähler, performed by Bähler

- "Good Old Shoe": written by Edgar Winter, performed by Nelson and Pops Staples

- "Classical Allegro": written by Marc Ferrari and Nancy Hieronymous

- "Courage Mom": written by Merle Haggard and performed by Merle Haggard and the Strangers

- "Barracuda": written by Heart, referenced by Woody Harrelson in character

- "I Love the Nightlife": written by Alicia Bridges and Susan Hutcheson

- "God Bless the Men of the 303": written by Huey Lewis, performed by Lewis, Scott Mathews, and Johnny Colla

- "Wag the Dog": written and performed by Mark Knopfler

Reception

On Rotten Tomatoes, Wag the Dog has an approval rating of 86%, based on 76 reviews, with an average rating of 7.4/10. The site's critical consensus reads: "Smart, well-acted, and uncomfortably prescient political satire from director Barry Levinson and an all-star cast."[10] On Metacritic, which assigns a weighted average rating, the film has a score of 73 out of 100, based on 22 critics, indicating "generally favorable reviews".[11]

Roger Ebert awarded the film four stars of four, and wrote in his review for the Chicago Sun-Times, "The movie is a satire that contains just enough realistic ballast to be teasingly plausible; like Dr. Strangelove, it makes you laugh, and then it makes you wonder."[12] He ranked it as his tenth favorite film of 1997.[13]

Ann Hornaday of The Washington Post rated it at number 12 on her list of the best political movies ever made.[14]

Accolades

Home media

Wag the Dog was released on VHS November 3, 1998, and on DVD November 15, 2005.[27][28] It is not available on Blu-ray.[29]

Television adaptation

On April 27, 2017, Deadline reported that Barry Levinson, Robert De Niro and Tom Fontana were developing a television series based on the film for HBO. De Niro's TriBeCa Productions was to co-produce, along with Levinson's and Fontana's companies.[30]

"Wag the dog" term and usage

The political phrase, "wag the dog", is used to indicate attention that is purposely being diverted from something of greater importance to something of lesser importance. The idiom stems from the 1870s. In a local newspaper, The Daily Republican: "Calling to mind Lord Dundreary's conundrum, the Baltimore American thinks that for the Cincinnati Convention to control the Democratic party would be the 'tail wagging the dog'."[31]

The phrase, then and now, indicates a backwards situation in which a small and seemingly unimportant entity (the tail) controls a bigger, more important one (the dog). It was used again in the 1960s. The film became a "reality" the year after it was released, due to the Clinton–Lewinsky scandal. Days after admitting to wrongdoing, President Bill Clinton ordered missile strikes against two countries, Afghanistan and Sudan.[32] During his impeachment proceedings, Clinton also bombed Iraq, drawing further "wag the dog" accusations,[33] and with the scandal still on the public's mind in March 1999, his administration launched a bombing campaign against Yugoslavia.[34]

See also

- Astroturfing, a controversial public relations practice depicted in the film

- Canadian Bacon and Wrong Is Right, films about an American war started for similar reasons

References

- 1 2 Turan, Kenneth (December 24, 1997). "'Wag the Dog' Is a Comedy With Some Real Bite to It". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on April 3, 2019. Retrieved April 18, 2017.

A gloriously cynical black comedy that functions as a wicked smart satire on the interlocking world of politics and show business ...

- ↑ "Wag the Dog (1997)". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on November 19, 2018. Retrieved April 2, 2017.

- ↑ "Wag the Dog Back In Spotlight". CNN. August 20, 1998. Archived from the original on September 15, 2012. Retrieved May 23, 2013.

- ↑ "Cohen criticizes 'wag the dog' characterization". CNN. March 23, 2004. Archived from the original on June 8, 2019. Retrieved October 8, 2018.

- ↑ Reed, Julia (April 11, 1999). "Welcome to Wag the Dog Three". The Independent. Archived from the original on December 8, 2019. Retrieved November 18, 2019.

- ↑ "Idiom: wag the dog". UsingEnglish.com. Archived from the original on May 16, 2011. Retrieved May 22, 2011.

- ↑ "Tiger Plays It Cool Under Big-cat Pressure". Orlando Sentinel. April 5, 1998. Archived from the original on July 1, 2015. Retrieved April 5, 2013.

- ↑ Welkos, Robert W. (May 11, 1998). "Giving Credit Where It's Due". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on August 16, 2021. Retrieved November 13, 2010.

- ↑ Byrne, Bridget (December 23, 1997). "Woof and Warp of "Dog" Screen Credit". E! Online. Archived from the original on November 6, 2018. Retrieved June 1, 2011.

- ↑ "Wag The Dog". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on May 20, 2021. Retrieved June 9, 2021.

- ↑ "Wag The Dog". Metacritic. Archived from the original on March 8, 2016. Retrieved December 26, 2011.

- ↑ Ebert, Roger (January 2, 1998). "Wag The Dog". RogerEbert.com. Ebert Digital LLC. Archived from the original on April 19, 2017. Retrieved April 18, 2017.

- ↑ Ebert, Roger (December 31, 1997). "The Best 10 Movies of 1997". RogerEbert.com. Ebert Digital LLC. Archived from the original on April 4, 2020. Retrieved February 22, 2019.

- ↑ Hornaday, Ann (January 23, 2020). "Perspective | The 34 best political movies ever made". Washington Post. Archived from the original on January 14, 2022. Retrieved January 24, 2020.

- ↑ "The 70th Academy Awards (1998) Nominees and Winners". Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. AMPAS. Archived from the original on November 9, 2014. Retrieved November 19, 2011.

- ↑ "Nominees/Winners". Casting Society of America. Archived from the original on August 16, 2018. Retrieved January 6, 2019.

- ↑ "Berlinale: 1998 Prize Winners". berlinale.de. Archived from the original on December 23, 2019. Retrieved August 15, 2022.

- ↑ "BAFTA Awards: Film in 1999". BAFTA. 1999. Archived from the original on March 7, 2016. Retrieved September 16, 2016.

- ↑ "The BFCA Critics' Choice Awards :: 1997". Broadcast Film Critics Association. Archived from the original on December 12, 2008. Retrieved January 7, 2014.

- ↑ "Wag the Dog – Golden Globes". HFPA. Archived from the original on June 21, 2021. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- ↑ "1997 Award Winners". National Board of Review. Archived from the original on May 28, 2021. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- ↑ "Past Awards". National Society of Film Critics. December 19, 2009. Archived from the original on May 31, 2015. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- ↑ "2nd Annual Film Awards (1997)". Online Film & Television Association. Archived from the original on October 16, 2020. Retrieved May 15, 2021.

- ↑ "1998 Satellite Awards". Satellite Awards. Archived from the original on May 2, 2021. Retrieved August 24, 2021.

- ↑ "The 4th Annual Screen Actors Guild Awards". Screen Actors Guild Awards. Archived from the original on November 1, 2011. Retrieved May 21, 2016.

- ↑ "Writers Guild Awards Winners". WGA. 2010. Archived from the original on May 25, 2012. Retrieved March 7, 2019.

- ↑ Levinson, Barry, Wag the Dog, ISBN 0780623959

- ↑ Levinson, Barry (November 15, 2005), Wag The Dog, Warner Bros., archived from the original on August 6, 2022, retrieved August 6, 2022

- ↑ "Wag The Dog Blu-ray", Blu-ray.com, archived from the original on October 11, 2019, retrieved May 4, 2023

- ↑ Petski, Denise (April 27, 2017). "'Wag The Dog' Comedy Series In Works At HBO". Deadline Hollywood. Penske Business Media, LLC. Archived from the original on April 29, 2017. Retrieved April 27, 2017.

- ↑ Wei Kong, Wong (November 19, 2016). "A dog's life". The Business Times. Archived from the original on December 8, 2019. Retrieved November 18, 2019.

- ↑ Dallek, Robert (August 21, 1998). "Are Clinton's Bombs Wagging the Dog?". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on December 8, 2019. Retrieved November 18, 2019.

- ↑ Saletan, William (December 20, 1998). "Wag the Doubt". Slate.com. Archived from the original on December 8, 2019. Retrieved January 4, 2020.

- ↑ Sciolino, Elaine; Bronner, Ethan (April 18, 1999). "How a President, Distracted by Scandal, Entered Balkan War". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 12, 2019. Retrieved November 18, 2019.