Wakulla County | |

|---|---|

Wakulla County Courthouse | |

Seal | |

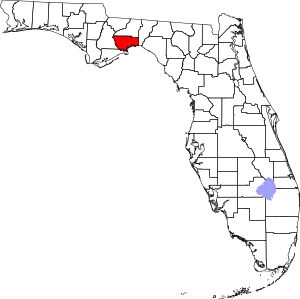

Location within the U.S. state of Florida | |

Florida's location within the U.S. | |

| Coordinates: 30°09′N 84°23′W / 30.15°N 84.38°W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| Founded | March 11, 1843 |

| Named for | Wakulla River |

| Seat | Crawfordville |

| Largest city | Sopchoppy |

| Area | |

| • Total | 736 sq mi (1,910 km2) |

| • Land | 606 sq mi (1,570 km2) |

| • Water | 129 sq mi (330 km2) 17.6% |

| Population (2020) | |

| • Total | 33,764 |

| • Density | 55/sq mi (21/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (Eastern) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (EDT) |

| Congressional district | 2nd |

| Website | www |

Wakulla County is a county located in the Big Bend region in the northern portion of the U.S. state of Florida. As of the 2020 census, the population was 33,764. Its county seat is Crawfordville.[1]

Wakulla County is part of the Tallahassee metropolitan area.

Wakulla County has a near-absence of any municipal population, with two small municipalities holding about 3% of the population. The county seat, Crawfordville, is one of only two unincorporated county seats among Florida's 67 counties.

History

First Spanish period

In 1528, Pánfilo de Narváez found his way to what would be Wakulla County from the future Pinellas County, Florida, camping at the confluence of the Wakulla and St. Marks rivers. Narváez determined this was a very suitable spot for a fort. In 1539, Hernando de Soto's expedition passed through La Florida with a similar route.

The Fort San Marcos de Apalache began with a wooden fort in the late 1600s. The vicinity around the fort was not settled until 1733. Spanish colonial officials began constructing a stone fort, which was unfinished in the mid-1760s when Great Britain took over.

British period

The British divided Florida into East Florida, which included present-day Wakulla County, and West Florida. The boundary was the Apalachicola River; at that time, West Florida extended all the way to the Mississippi River. Twenty years later when the Spanish returned, they kept the East and West divisions, with the administrative capitals remaining at St. Augustine and Pensacola, respectively.

Second Spanish period

The area to become Wakulla County was an active place in the early 19th century. A former British officer named William Augustus Bowles attempted to unify and lead 400 Creek Indians against the Spanish outpost of San Marcos, capturing it. This provoked Spain, and a Spanish flotilla arrived some five weeks later to restore control.

In 1818, General Andrew Jackson invaded the area, capturing Fort San Marcos. Two captive British citizens, Robert Ambrister and Alexander Arbuthnot, were tried, found guilty of inciting Indian raids, and executed under Jackson's authority – causing a diplomatic nightmare between the U.S. and Britain. The U.S. Army garrison of 200 infantry and artillery men occupied the fort for the better part of a year (1818-1819).

In 1821, Florida was ceded to the United States and Fort St. Marks, as the Americans called it, was again garrisoned by U.S. troops.

Florida's territorial period

In 1824, the fort was abandoned and turned over to the Territory of Florida.

By 1839, the fort was returned to the Federal government and a merchant marine hospital was built. The hospital provided care for seamen and area yellow fever victims.

American forts in Wakulla County

- 1840 - Camp Lawson, northwest of Wakulla and northeast of Ivan, on the St. Marks River. A log stockade also known as Fort Lawson (2).

- 1841-1842 - Fort Many located near Wakulla Springs.

- 1839 - Fort Number Five (M) located near Sopchoppy.

- 1839-1843 - Fort Stansbury was located on the Wakulla River 9 miles (14 km) from St. Marks.

- 1841-1843 - Fort Port Leon. Abandoned after a hurricane destroyed it. Site was later used for a CSA Army artillery battery.

- 1839 - James Island Post located on James Island.[2]

Antebellum Wakulla

Wakulla County was created from Leon County in 1843. It may (although this is disputed) be named for the Timucuan Indian word for "spring of water" or "mysterious water". This is in reference to Wakulla County's greatest natural attraction, Wakulla Springs, which is one of the world's largest freshwater springs, both in terms of depth and water flow. In 1974, the water flow was measured at 1.23 billion US gallons (4,700,000 m3) per day—the greatest recorded flow ever for a single spring.

In an 1856 book, adventurer Charles Lanman wrote of the springs:

An adequate idea of this mammoth spring could never be given by pen or pencil; but when once seen, on a bright calm day, it must ever after be a thing to dream about and love. It is the fountain-head of a river... and is of sufficient volume to float a steamboat, if such an affair had yet dared to penetrate this solemn wilderness... It wells up in the very heart of a dense cypress swamp, is nearly round in shape, measures some four hundred feet in diameter, and is in depth about one hundred and fifty feet, having at its bottom an immense horizontal chasm, with a dark portal, from one side of which looms up a limestone cliff, the summit of which is itself nearly fifty feet beneath the spectator, who gazes upon it from the sides of a tiny boat. The water is so astonishlingly clear that even a pin can be seen on the bottom in the deepest places, and of course every animate and inanimate object which it contains is fully exposed to view. The apparent color of the water from the shore is greenish, but as you look perpendicularly into it, it is colorless as air, and the sensation of floating upon it is that of being suspended in a balloon; and the water is so refractive, that when the sun shines brilliantly every object you see is enveloped in the most fascinating prismatic hues.

Another possible origin for the name Wakulla, not as widely accepted, is that it means "mist" or "misting", perhaps in reference to the Wakulla Volcano, a 19th-century phenomenon in which a column of smoke could be seen emerging from the swamp for miles.

The town of Port Leon was once a thriving cotton-shipping hub, with a railroad from Tallahassee that carried over 50,000 tons of cotton a year to be put on ships, usually for shipment direct to Europe. Port Leon was the sixth-largest town in Florida, with 1,500 residents. However, a hurricane and the accompanying storm surge wiped out the entire town. New Port (today known as Newport, Florida) was built two miles (3 km) upstream but never quite achieved the prosperity of Port Leon.[3][4]

Civil War

During the Civil War, Wakulla County was blockaded from 1861 to 1865 by a Union Navy squadron at the mouth of the St. Marks River. Confederates took the old Spanish fort known as San Marcos de Apalache, or Fort St. Marks, and renamed it Fort Ward.

The Battle of Natural Bridge eventually stopped the Union force that intended to take Fort Ward and nearby Tallahassee, the only Confederate state capital other than Austin Texas which had not been captured. The Union was not able to land all of its forces, but they still outnumbered the Confederates, who chose to make their stand at a place where the St. Marks River goes underground: the "Natural Bridge" referred to. However, the Confederate Army had over a day to prepare its defenses, and the Union Army retreated. Most of the dead were African-American Union soldiers.

20th century and beyond

In Gloria Jahoda's book The Other Florida, she writes movingly of the extreme poverty of Wakulla County from the early 1900s to 1966 when Wakulla still had no doctor and no dentist, few stores, and a county newspaper produced just once a month on a mimeograph machine.[4]

Today, Wakulla has several doctors and dentists, several supermarkets and big-box retailers, a golf resort, and a thriving seafood business.[5]

Etymology

The name Wakulla is corrupted from Guacara. Guacara is a Spanish phonetic spelling of an original Indian name, and Wakulla is a Muskhogean pronunciation of Guacara. The Spanish "Gua" is the equivalent of the Creek "wa", and as the Creek alphabet does not exhibit an "R" sound, the second element "cara" would have been pronounced "kala" by the Creeks. The Creek voiceless "L" is always substituted for the Spanish "R". Thus the word Guacara was pronounced Wakala by the Seminoles who are Muskhogean in their origin and language.

Because Wakulla was probably a Timucuan word, it is unlikely that its meaning will ever be known. It may contain the word kala, which signified a "spring of water" in some Indian dialects.[6]. It may refer to the Whip-poor-will, known as waxkula in Creek.[7]

Geography

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the county has a total area of 736 square miles (1,910 km2), of which 606 square miles (1,570 km2) is land and 129 square miles (330 km2) (17.6%) is water.[8]

Wakulla County was added to the Tallahassee, Florida Metropolitan Statistical Area (MSA) in 1973. The county was removed from the Tallahassee MSA in 1983. It was re-added to the MSA (for the second time) in 2003.[9]

Adjacent counties

- Leon County - north

- Liberty County - west

- Franklin County - southwest

- Jefferson County - east

National protected areas

State and local protected areas

Demographics

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1850 | 1,955 | — | |

| 1860 | 2,839 | 45.2% | |

| 1870 | 2,506 | −11.7% | |

| 1880 | 2,723 | 8.7% | |

| 1890 | 3,117 | 14.5% | |

| 1900 | 5,149 | 65.2% | |

| 1910 | 4,802 | −6.7% | |

| 1920 | 5,129 | 6.8% | |

| 1930 | 5,468 | 6.6% | |

| 1940 | 5,463 | −0.1% | |

| 1950 | 5,258 | −3.8% | |

| 1960 | 5,257 | 0.0% | |

| 1970 | 6,308 | 20.0% | |

| 1980 | 10,887 | 72.6% | |

| 1990 | 14,202 | 30.4% | |

| 2000 | 22,863 | 61.0% | |

| 2010 | 30,776 | 34.6% | |

| 2020 | 33,764 | 9.7% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[10] 1790-1960[11] 1900-1990[12] 1990-2000[13] 2010-2015[14] 2019[15] | |||

2020 census

| Race | Pop 2010 | Pop 2020 | % 2010 | % 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| White (NH) | 24,472 | 25,987 | 79.52% | 76.97% |

| Black or African American (NH) | 4,406 | 4,202 | 14.32% | 12.45% |

| Native American or Alaska Native (NH) | 174 | 154 | 0.57% | 0.46% |

| Asian (NH) | 166 | 198 | 0.54% | 0.59% |

| Pacific Islander (NH) | 17 | 19 | 0.06% | 0.06% |

| Some Other Race (NH) | 29 | 126 | 0.09% | 0.37% |

| Mixed/Multi-Racial (NH) | 496 | 1,501 | 1.61% | 4.45% |

| Hispanic or Latino | 1,016 | 1,577 | 3.3% | 4.67% |

| Total | 30,776 | 33,764 |

As of the 2020 United States census, there were 33,764 people, 11,382 households, and 8,362 families residing in the county.

2000 census

As of the census[20] of 2000, there were 22,863 people, 8,450 households, and 6,236 families residing in the county. The population density was 38 inhabitants per square mile (15/km2). There were 9,820 housing units at an average density of 16 per square mile (6/km2). The racial makeup of the county was 86.10% White, 11.51% Black or African American, 0.59% Native American, 0.25% Asian, 0.03% Pacific Islander, 0.29% from other races, and 1.23% from two or more races. 1.94% of the population were Hispanic or Latino of any race.

There were 8,450 households, out of which 35.60% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 57.10% were married couples living together, 12.40% had a female householder with no husband present, and 26.20% were non-families. 22.00% of all households were made up of individuals, and 7.00% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.57 and the average family size was 2.99. In the county, the population was spread out, with 25.60% under the age of 18, 7.60% from 18 to 24, 31.70% from 25 to 44, 24.70% from 45 to 64, and 10.30% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 37 years. For every 100 females, there were 107.30 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 106.80 males.

The median income for a household in the county was $37,149, and the median income for a family was $42,222. Males had a median income of $29,845 versus $24,330 for females. The per capita income for the county was $17,678. About 9.30% of families and 11.30% of the population were below the poverty line, including 15.40% of those under age 18 and 15.10% of those age 65 or over.

Politics

| Year | Republican | Democratic | Third party | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | |

| 2020 | 12,874 | 69.79% | 5,351 | 29.01% | 223 | 1.21% |

| 2016 | 10,512 | 68.07% | 4,348 | 28.15% | 584 | 3.78% |

| 2012 | 9,290 | 63.21% | 5,175 | 35.21% | 232 | 1.58% |

| 2008 | 8,877 | 61.75% | 5,311 | 36.94% | 188 | 1.31% |

| 2004 | 6,777 | 57.61% | 4,896 | 41.62% | 90 | 0.77% |

| 2000 | 4,512 | 52.54% | 3,838 | 44.70% | 237 | 2.76% |

| 1996 | 2,933 | 40.91% | 3,056 | 42.63% | 1,180 | 16.46% |

| 1992 | 2,586 | 38.52% | 2,320 | 34.55% | 1,808 | 26.93% |

| 1988 | 3,158 | 65.72% | 1,605 | 33.40% | 42 | 0.87% |

| 1984 | 3,088 | 67.75% | 1,470 | 32.25% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1980 | 2,021 | 47.26% | 2,082 | 48.69% | 173 | 4.05% |

| 1976 | 1,580 | 38.80% | 2,353 | 57.78% | 139 | 3.41% |

| 1972 | 2,466 | 82.01% | 539 | 17.92% | 2 | 0.07% |

| 1968 | 247 | 10.49% | 440 | 18.68% | 1,668 | 70.83% |

| 1964 | 1,270 | 62.78% | 753 | 37.22% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1960 | 379 | 24.85% | 1,146 | 75.15% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1956 | 393 | 26.79% | 1,074 | 73.21% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1952 | 375 | 24.24% | 1,172 | 75.76% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1948 | 72 | 5.22% | 997 | 72.30% | 310 | 22.48% |

| 1944 | 73 | 6.69% | 1,018 | 93.31% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1940 | 70 | 4.98% | 1,336 | 95.02% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1936 | 45 | 3.08% | 1,417 | 96.92% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1932 | 20 | 1.89% | 1,036 | 98.11% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1928 | 66 | 12.18% | 470 | 86.72% | 6 | 1.11% |

| 1924 | 34 | 8.74% | 332 | 85.35% | 23 | 5.91% |

| 1920 | 119 | 17.81% | 530 | 79.34% | 19 | 2.84% |

| 1916 | 121 | 21.49% | 387 | 68.74% | 55 | 9.77% |

| 1912 | 25 | 8.96% | 215 | 77.06% | 39 | 13.98% |

| 1908 | 56 | 16.28% | 239 | 69.48% | 49 | 14.24% |

| 1904 | 39 | 13.78% | 233 | 82.33% | 11 | 3.89% |

County representation

| Wakulla County Government | ||

|---|---|---|

| Position | Name | Party |

|

| ||

| Commissioner | Ralph Thomas | Republican |

| Commissioner | Fred Nichols II | Republican |

| Commissioner | Mike Kemp | Republican |

| Commissioner | Quincee MesserSmith | Republican |

| Commissioner | Chuck Hess | Democrat |

| Sheriff | Jared Miller | Republican |

| County Judge | Brian Miller | Republican |

| Clerk of the Court | Greg James | Republican |

| Property Appraiser | Ed Brimner | Republican |

| School Superintendent | Bobby Pearce | Republican |

| Elections Supervisor | Joe Morgan | Republican |

| Tax Collector | Liza Craze | Republican |

Transportation

Roads

Although there are no Interstate highways in Wakulla County, several major routes pass through the area, including U.S. Route 98 and U.S. Route 319. Other important roads in the county include State Road 267, State Road 363 and County Road 375.[23]

Railroads

No railroads currently operate within Wakulla County.

In the past the Georgia, Florida and Alabama Railroad passed through Sopchoppy on its route between Tallahassee and Carrabelle until its abandonment in 1948; that portion of the line was referred to as the Sumatra Leaf Line, referring to a tobacco grown in the area. South of Sopchoppy the line followed H.T. Smith Road. The railroad bridge crossing the Ochlocknee River at MacIntyre still exists as pilings blocking all but a portion of the river on the south side.[24][25] while the Tallahassee Railroad, the first railroad in Florida, was abandoned by its successor, the Seaboard Coast Line Railroad, in 1983.

Airports

The Wakulla County Airport (2J0), located south of Panacea, is a small public-use airport with a single 2,600-foot (790 m), north–south turf runway.[26] This airfield was originally constructed during World War II, as an emergency landing strip for Army Air Corps aircraft which trained and patrolled along the Gulf Coast, most of which belonged to the 3rd Army Air Corps out of Dale Mabry Field Army Air Base in Tallahassee. After the war, the air strip was turned over to the county for civilian uses.

Seaports

St. Marks is a small commercial seaport. Panacea and Ochlockonee Bay also support small fishing fleets.

Education

Wakulla County is served by the Wakulla school district with the following schools:[27]

- Crawfordville Elementary School

- C.O.A.S.T. Charter School

- Medart Elementary School

- Shadeville Elementary School

- Riversink Elementary School

- Riversprings Middle School

- Wakulla Middle School

- Wakulla High School

- Wakulla Christian School

The former Sopchoppy Elementary School now serves as the Sopchoppy Education Center, a Pre-K, adult, and second chance school.

The former Shadeville High School served African-American students from 1931 to 1967.

Library

The Wakulla County Public Library is the main library of Wakulla County and is a part of the Wilderness Coast Public Libraries.[28]

Communities

Towns

Census-designated places

Other unincorporated communities

- Arran

- Buckhorn

- Curtis Mills

- Hyde Park

- Ivan

- Medart

- Newport

- Port Leon

- Sanborn

- Shadeville

- Shell Point

- Smith Creek

- Spring Creek

- Wakulla

- Wakulla Beach

See also

Notes

References

- ↑ "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Archived from the original on July 12, 2012. Retrieved June 7, 2011.

- ↑ "Florida Forts: page 2". Archived from the original on April 26, 2005. Retrieved April 29, 2013.

- ↑ "Historical Places". Wakullacountytdc.com. Archived from the original on March 3, 2012. Retrieved April 29, 2013.

- 1 2 Jahoda, Gloria (1967). The Other Florida, Florida Classics. ISBN 978-0-912451-04-6.

- ↑ "Wakulla County Chamber of Commerce". Wakullacountychamber.com. Archived from the original on May 29, 2013. Retrieved April 29, 2013.

- ↑ Simpson, J. Clarence (1956). Mark F. Boyd (ed.). Florida Place-Names of Indian Derivation. Tallahassee, Florida: Florida Geological Survey.

- ↑ Gatschet, Albert S. Peet, Stephen D. (ed.). "The American Antiquarian and Oriental Journal" (PDF). Wikimedia Commons. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 28, 2021.

- ↑ "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. February 12, 2011. Archived from the original on February 24, 2021. Retrieved April 23, 2011.

- ↑ "Metro Area History 1950–2020". U.S. Census Bureau. March 2020. Row 4179. Retrieved November 5, 2023.

- ↑ "U.S. Decennial Census". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on July 1, 2021. Retrieved June 16, 2014.

- ↑ "Historical Census Browser". University of Virginia Library. Archived from the original on August 11, 2012. Retrieved June 16, 2014.

- ↑ "Population of Counties by Decennial Census: 1900 to 1990". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 20, 2014. Retrieved June 16, 2014.

- ↑ "Census 2000 PHC-T-4. Ranking Tables for Counties: 1990 and 2000" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 18, 2014. Retrieved June 16, 2014.

- ↑ "State & County QuickFacts". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 13, 2014. Retrieved February 15, 2014.

- ↑ "QuickFacts. Florida counties". Archived from the original on January 23, 2020. Retrieved May 20, 2020.

- ↑ "Explore Census Data". data.census.gov. Archived from the original on May 18, 2022. Retrieved May 18, 2022.

- ↑ "Explore Census Data". data.census.gov. Archived from the original on May 18, 2022. Retrieved May 18, 2022.

- ↑ Bureau, US Census. "Census.gov". Census.gov. Archived from the original on October 23, 2019. Retrieved March 17, 2023.

- ↑ "About the Hispanic Population and its Origin". www.census.gov. Archived from the original on May 20, 2022. Retrieved May 18, 2022.

- ↑ "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on December 27, 1996. Retrieved May 14, 2011.

- ↑ Leip, David. "Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections". uselectionatlas.org. Archived from the original on July 9, 2018. Retrieved June 16, 2018.

- ↑ "Wakulla County Supervisor of Elections". Archived from the original on December 31, 2006. Retrieved January 9, 2007.

- ↑ Florida Atlas & Gazetteer (7th ed.). DeLorme. 2003. ISBN 0-89933-318-4.

- ↑ "Georgia, Florida & Alabama Railway, 1918 map". Archived from the original on September 10, 2015. Retrieved November 27, 2016.

- ↑ "Donald R. Hensley, Jr.'s Taplines". The story of the Georgia Florida & Alabama RR. Archived from the original on April 4, 2019. Retrieved January 9, 2007.

- ↑ "WCSB School List". Archived from the original on May 16, 2010.

- ↑ "Wilderness Coast Public Libraries". wildernesscoast.org. Archived from the original on September 13, 2019. Retrieved October 11, 2019.