Wallace Beery | |

|---|---|

Beery c. 1930 | |

| Born | Wallace Fitzgerald Beery April 1, 1885 Clay County, Missouri, U.S. |

| Died | April 15, 1949 (aged 64) |

| Resting place | Forest Lawn Memorial Park, Glendale, California, U.S. |

| Occupations |

|

| Years active | 1904–1949 |

| Spouses | |

| Children | 1 |

| Relatives |

|

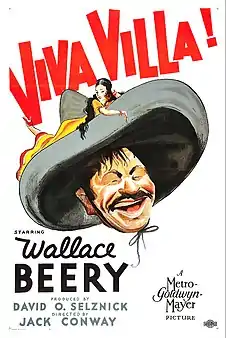

Wallace Fitzgerald Beery (April 1, 1885 – April 15, 1949) was an American film and stage actor.[1] He is best known for his portrayal of Bill in Min and Bill (1930) opposite Marie Dressler, as General Director Preysing in Grand Hotel (1932), as Long John Silver in Treasure Island (1934), as Pancho Villa in Viva Villa! (1934), and his title role in The Champ (1931), for which he won the Academy Award for Best Actor. Beery appeared in some 250 films during a 36-year career. His contract with Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer stipulated in 1932 that he would be paid $1 more than any other contract player at the studio. This made Beery the highest-paid film actor in the world during the early 1930s. He was the brother of actor Noah Beery and uncle of actor Noah Beery Jr.

For his contributions to the film industry, Beery was posthumously inducted into the Hollywood Walk of Fame with a motion-picture star in 1960. His star is located at 7001 Hollywood Boulevard.[2]

Early life

Beery was born the youngest of three boys in 1885 in Clay County, Missouri, near Smithville.[3] The Beery family left the farm in the 1890s and moved to nearby Kansas City, Missouri, where the father was a police officer. A fourth brother, Charles, was born in 1880 but survived only a day after his birth.[4] There might have been an older sister but information is faint.

Beery attended the Chase School in Kansas City and took piano lessons as well, but showed little love for academic matters. He ran away from home twice, the first time returning after a short time, quitting school and working in the Kansas City train yards as an engine wiper.[3] Beery ran away from home a second time at age 16, and joined the Ringling Brothers Circus as an assistant elephant trainer. He left two years later, after being clawed by a leopard.

Career

.jpg.webp)

_(3109252361).jpg.webp)

Early career

Wallace Beery joined his older brother Noah in New York City in 1904, finding work in comic opera as a baritone, and began to appear on Broadway and in summer stock theatre. He appeared in The Belle of the West in 1905. His most notable early role came in 1907 when he starred in The Yankee Tourist to good reviews.[5]

Comedy film star – Essanay Studios

In 1913, he moved to Chicago to work for Essanay Studios. His first movie was likely a comedy short, His Athletic Wife (1913).

Beery was then cast as Sweedie, a Swedish maid character he played in drag in a series of short comedy films from 1914 to 1916. Sweedie Learns to Swim (1914) co-starred Ben Turpin. Sweedie Goes to College (1915) starred Gloria Swanson, whom Beery married the following year.[6]

Other Beery films (mostly shorts) from this period included In and Out (1914), The Ups and Downs (1914), Cheering a Husband (1914), Madame Double X (1914), Ain't It the Truth (1915), Two Hearts That Beat as Ten (1915), and The Fable of the Roistering Blades (1915).

The Slim Princess (1915), with Francis X. Bushman, was one of his earliest feature-length films. Beery also did The Broken Pledge (1915) and A Dash of Courage (1916), both with Swanson.

Beery played a German soldier in The Little American (1917) with Mary Pickford, directed by Cecil B. De Mille. He did some comedies for Mack Sennett, Maggie's First False Step (1917) and Teddy at the Throttle (1917), but he gradually left that genre and specialized in portrayals of villains prior to becoming a major leading man during the sound era.

Villainous roles

In 1917, Beery portrayed Pancho Villa in Patria at a time when Villa was still active in Mexico. (Beery reprised the role 17 years later in Viva Villa!.)

Beery was a villainous German in The Unpardonable Sin (1919) with Blanche Sweet. For Paramount, he did The Love Burglar (1919) with Wallace Reid; Victory (1919), with Jack Holt; Behind the Door (1919), as another villainous German; and The Life Line (1919) with Holt.

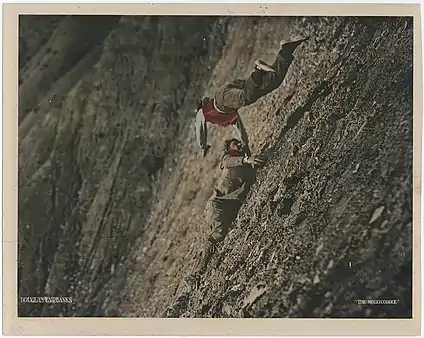

Beery was the villain in five major releases in 1920: 813; The Virgin of Stamboul for director Tod Browning; The Mollycoddle with Douglas Fairbanks, in which Fairbanks and Beery fistfought as they tumbled down a steep mountain (see the photograph in the gallery below); and in the noncomedic Western The Round-Up starring Roscoe Arbuckle as an obese cowboy in a well-received serious film with the tagline "Nobody loves a fat man." Beery continued his villainy cycle that year with The Last of the Mohicans, playing Magua.

Beery had a supporting part in The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse (1920) with Rudolph Valentino. He was a villainous Tong leader in A Tale of Two Worlds (1921), and was the bad guy again in Sleeping Acres (1922), Wild Honey (1922), and I Am the Law (1922), which also featured his brother Noah Beery Sr.

Historical films

_-_1.jpg.webp)

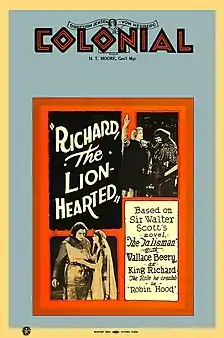

Beery had a large then-rare heroic part as King Richard I (Richard the Lion-Hearted) in Robin Hood (1922), starring Douglas Fairbanks as Robin Hood. The lavish movie was a huge success and spawned a sequel the following year starring Beery in the title role of Richard the Lion-Hearted.

Beery had an important unbilled cameo as "the Ape-Man" in A Blind Bargain (1922) starring Lon Chaney (Beery is seen crouching, in full ape-man make-up, in the background of some of the movie's posters), and a supporting role in The Flame of Life (1923). He played another historical king, King Philip IV of Spain in The Spanish Dancer (1923) with Pola Negri.

Beery starred in an action melodrama, Stormswept (1923) for FBO Films alongside his elder brother, Noah Beery Sr. The tagline on the movie's posters was "Wallace and Noah Beery – The Two Greatest Character Actors on the American Screen".

Beery played his third royal, the Duc de Tours, in Ashes of Vengeance (1923) with Norma Talmadge, then did Drifting (1923) with Priscilla Dean for director Browning.

Beery had the title role in Bavu (1923), about Bolsheviks and the Russian Revolution. He co-starred with Buster Keaton in the comedy Three Ages (1923), the first feature Keaton wrote, produced, directed, and starred in.

Beery was a villain in The Eternal Struggle (1923), a Mountie drama, produced by Louis B. Mayer, who eventually became crucial to Beery's career. He was reunited with Dean and Browning in White Tiger (1923), then played the title role in the aforementioned Richard the Lion-Hearted (1923), a sequel to Robin Hood based on Sir Walter Scott's The Talisman; a print of Richard the Lion-Hearted is held at the Archives du Film du CNC in Bois d'Arcy.[7]

Beery was in The Drums of Jeopardy (1923) and had a supporting role in The Sea Hawk (1924) for director Frank Lloyd. He also appeared in a supporting role for Clarence Brown's The Signal Tower (1925) starring Virginia Valli and Rockliffe Fellowes.

Paramount

.jpg.webp)

Beery signed a contract with Paramount Pictures. He had a support role in Adventure (1925) directed by Victor Fleming.

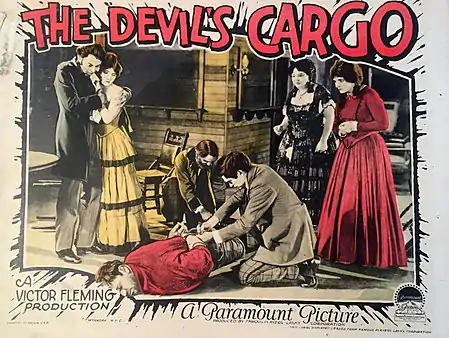

At First National, he was given the star role of Professor Challenger in Arthur Conan Doyle's dinosaur epic The Lost World (1925), arguably his silent performance most frequently screened in the modern era. Beery was top billed in Paramount's The Devil's Cargo (1925) for Victor Fleming, and supported in The Night Club (1925), The Pony Express (1925) for James Cruze, and The Wanderer (1925) for Raoul Walsh.

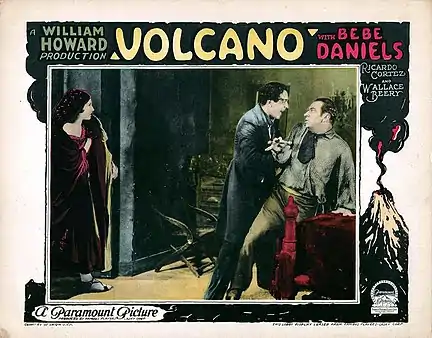

Beery starred in a comedy with Raymond Hatton, Behind the Front (1926), and he was a villain in Volcano! (1926). He was a bos'n in Old Ironsides (1926) for director James Cruze, with Charles Farrell in the romantic lead.

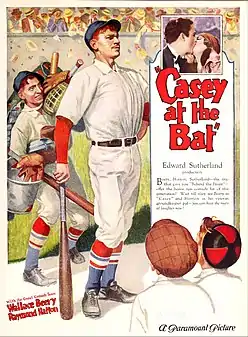

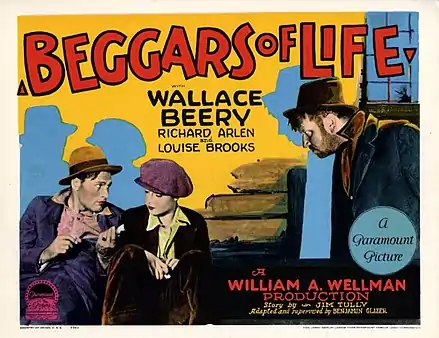

Beery had the title role in the baseball movie Casey at the Bat (1927). He was reunited with Hatton in Fireman, Save My Child (1927) and Now We're in the Air (1927). The latter also featured Louise Brooks, who was Beery's costar in Beggars of Life (1928), directed by William Wellman, which was Paramount's first part-talkie movie.

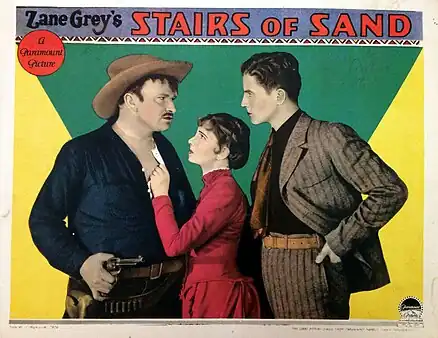

He made a fourth comedy with Hatton, Wife Savers (1929), then Beery starred in Chinatown Nights (1929) for Wellman, produced by a young David O. Selznick. This film was shot silent with the voices dubbed in by the actors afterward, which worked spectacularly well with Beery's resonant voice, although the technique was not used again during the silent era for another full-length feature. Beery then played in Stairs of Sand (1929), a Western also starring Jean Arthur (who played the leading lady in the Western film Shane 24 years later) before being fired by Paramount.

MGM

_trailer_1.jpg.webp)

Irving Thalberg signed Beery to Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM) as a character actor. The association began well when Beery played the savage convict Butch, a role originally intended for Lon Chaney (who died that same year), in the highly successful 1930 prison film The Big House, directed by George W. Hill; Beery was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Actor.

Beery's second film for MGM was also a huge success: Billy the Kid (1930), an early widescreen picture in which he played Pat Garrett. He supported John Gilbert in Way for a Sailor (1930) and Grace Moore in A Lady's Morals (1930), portraying P. T. Barnum in the latter.

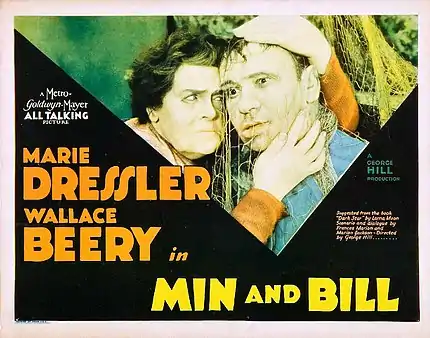

Stardom

Beery was well established as a leading man and top-rank character actor. The picture that really made him one of the cinema's foremost stars was Min and Bill (1930) opposite Marie Dressler and directed by George W. Hill, a sensational success.[8]

Beery made a third film with Hill, The Secret Six (1931), a gangster movie with Jean Harlow and Clark Gable in key supporting roles. The picture was popular, but was surpassed at the box office by The Champ, which Beery made with Jackie Cooper for director King Vidor. The film, especially written for Beery, was another box-office sensation. Beery shared the Best Actor Oscar with Fredric March. Though March received one vote more than Beery, Academy rules at the time—since rescinded—defined results within one vote of each other as "ties".[9] (An alternate account has MGM head Louis B. Mayer storming backstage at the Oscars and demanding that March and Beery share that year's Academy Award for Best Actor since the vote was so close.)

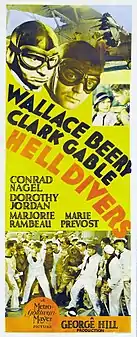

Beery's career went from strength to strength. Hell Divers (1932), a naval airplane epic also starring a young Clark Gable billed under Beery, was a big hit. So, too, was the all-star Grand Hotel (1932), in which Beery was billed fourth, under Greta Garbo, John Barrymore, and Joan Crawford, one of the very few times he would not be top billed for the rest of his career. In 1932, his contract with MGM stipulated that he be paid a dollar more than any other contract player at the studio, making him the world's highest-paid actor.

Beery was a German wrestler in Flesh (1932), a hit directed by John Ford, but Ford removed his directorial credit before the film opened, so the picture screened with no director listed despite being labeled "A John Ford Production" in the opening title card. Next Beery was in another all-star ensemble blockbuster, Dinner at Eight (1933), with Jean Harlow holding her own as Beery's comically bickering wife. This time, Beery was billed third, under Marie Dressler and John Barrymore.

Beery was lent to the new 20th Century Pictures for the boisterously fast-paced comedy/drama The Bowery (1933), also starring George Raft, Jackie Cooper, and Fay Wray, and featuring Pert Kelton, under the direction of Raoul Walsh. The picture was a smash hit.

Back at MGM, he played the title role of Pancho Villa in Viva Villa! (1933) and was reunited with Dressler in Tugboat Annie (1933), a massive hit. He was Long John Silver in Treasure Island (1934), described as a box-office "disappointment"[10] despite being MGM's third-largest hit of the season, and remains currently viewed as featuring one of Beery's iconic performances.

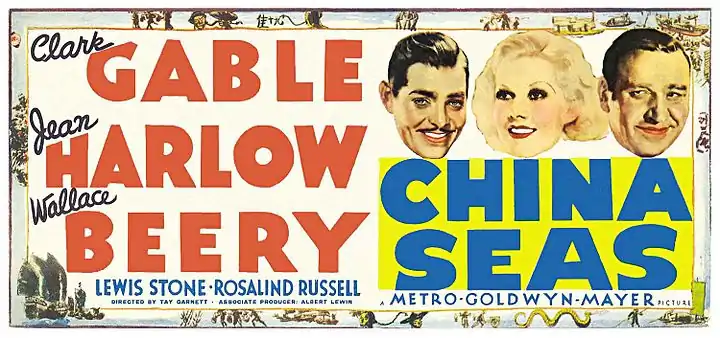

Beery returned to 20th Century Productions for The Mighty Barnum (1934), in which he played P. T. Barnum again. Back at MGM, he was a kindly sergeant in West Point of the Air (1935) and was in an all-star spectacular, China Seas (1935), this time billed beneath Clark Gable.

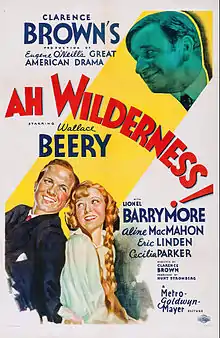

O'Shaughnessy's Boy (1935) reunited Beery and Jackie Cooper. He had the lead as the drunken uncle in MGM's adaptation of Ah, Wilderness! (1936) and went back to 20th Century – now 20th Century Fox – for A Message to Garcia (1936) with Barbara Stanwyck.

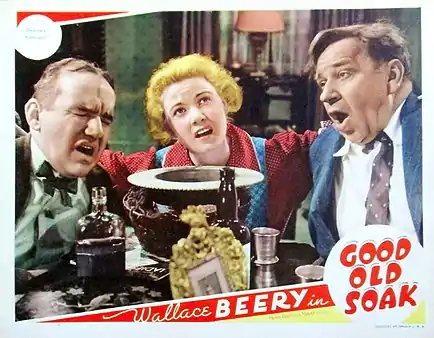

At MGM, he was in Old Hutch (1936) and The Good Old Soak (1937), then he was back at Fox for Slave Ship (1937), taking second billing under Warner Baxter, a rarity for Beery after Min and Bill catapulted his career into the stratosphere in 1931, during which he received top billing in all but six films (Min and Bill, Grand Hotel, Tugboat Annie, Dinner at Eight, China Seas with Gable and Harlow, and Slave Ship).

Decline

The status of Beery's films went into a decline. After an abrupt European vacation,[11][12] Beery was in The Bad Man of Brimstone (1938) with Dennis O'Keefe (and Noah Beery Sr. in a cameo role as a bartender), Port of Seven Seas (1938) with Maureen O'Sullivan, Stablemates (1938) with Mickey Rooney, Stand Up and Fight (1939) with Robert Taylor, Sergeant Madden (1939) with Tom Brown, Thunder Afloat (1939) with Chester Morris, The Man from Dakota (1940) with Dolores del Río, and 20 Mule Team (1940) with Marjorie Rambeau, Anne Baxter, and Noah Beery Jr., enjoying top billing in all of them.

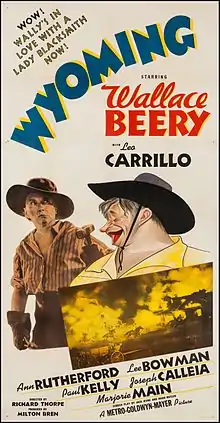

Wyoming (1940) teamed Beery with Marjorie Main. After The Bad Man (1941), which also stars Lionel Barrymore and future President of the United States Ronald Reagan, and was the remake of a Walter Huston picture, MGM reunited Beery and Main in Barnacle Bill (1941), The Bugle Sounds (1941), and Jackass Mail (1942).

Beery did a war film, a Technicolor comedy titled Salute to the Marines (1943), then was back with Main in Rationing (1944). Barbary Coast Gent (1944), an extremely broad Western comedy in which Beery played a bombastic con man, teamed him with Binnie Barnes. He did another war film, This Man's Navy (1945), then made another Western with Main, Bad Bascomb (1946), a huge hit, helped primarily by Margaret O'Brien's casting.

The Mighty McGurk (1947) put Beery with another child star of the studio, Dean Stockwell. Alias a Gentleman (1947) was the first of Beery's films to lose money during the sound era. Beery received top billing for the smash hit A Date with Judy (1949), a hugely popular musical featuring Elizabeth Taylor. Beery's last film, again featuring Main, Big Jack (1949), also lost money according to Mannix's reckoning.[13] Beery died of a heart attack three days after the picture's release.

Personal life

.png.webp)

.png.webp)

First marriage

On March 27, 1916, at the age of 30, Beery married 17-year-old actress Gloria Swanson in Los Angeles.[14] The two had co-starred in Sweedie Goes to College.[6] Although Beery had enjoyed popularity with his Sweedie shorts, his career had taken a dip, and during the marriage to Swanson, he relied on her as a breadwinner. According to Swanson's autobiography, Beery raped her on their wedding night, and later tricked her into swallowing an abortifacient when she was pregnant, which caused her to lose their child.[15] Swanson filed for divorce in 1917 and it was finalized in 1918.[14]

Second marriage and adoption

On August 4, 1924, Beery married actress Rita Gilman (née Mary Areta Gilman; 1898–1986) in Los Angeles.[16] The couple adopted Carol Ann Priester (1930–2013), daughter of Rita Beery's mother's half-sister, Juanita Priester (née Caplinger; 1899–1931) and her husband, Erwin William Priester (1897–1969). After 14 years of marriage, Rita filed for divorce on May 1, 1939, in Carson City, Ormsby County, Nevada. Within 20 minutes of filing, she won the decree. Rita remarried 15 days later, on May 16, 1939, to Jessen Albert D. Foyt (1907–1945), filing her marriage license with the same county clerk in Carson City.

Alleged fatal altercation

In December 1937, comedic actor and Three Stooges founder Ted Healy was involved in a drunken altercation at Cafe Trocadero on the Sunset Strip. E. J. Fleming, in his 2005 book, The Fixers: Eddie Mannix, Howard Strickling and the MGM Publicity Machine, asserts that Healy was attacked by three men: future James Bond producer Albert "Cubby" Broccoli, local mob figure Pat DiCicco (who was Broccoli's cousin as well as the former husband of Thelma Todd and the future husband of Gloria Vanderbilt), and Wallace Beery. Fleming writes that this beating led to Healy's death a few days later.[11][12]

There is no documentation in contemporaneous news reports that either Beery or DiCicco was present.[17] Broccoli admitted that he was indeed involved in a fistfight with Healy at the Trocadero.[18] The official autopsy names Healy's cause of death as acute toxic nephritis secondary to acute and chronic alcoholism.[19]

Second adoption

Around December 1939, Beery, recently divorced, adopted a seven-month-old girl, Phyllis Ann Beery.[20] Phyllis appeared in MGM publicity photos when adopted, but was never mentioned again.[21] Beery told the press he had taken the girl in from a single mother, recently divorced, but he had filed no official adoption papers.[22]

Working relationship with peers

.jpg.webp)

Beery was considered misanthropic and difficult to work with by many of his colleagues. Robert Young described Beery as a "shitty person". On set, he often never bothered to learn his lines and instead chose to take from other actors' characters and then resent it when his theft was pointed out. When prompting for another actor's close-up, Beery would read the wrong lines, making it harder for his co-stars to meet their marks. Beery was "loathed by everybody, and happily oblivious".[23]

Mickey Rooney was one of Beery's few co-stars to consistently speak highly of him in subsequent decades. In his memoir, Rooney described Beery as "... a lovable, shambling kind of guy who never seemed to know that his shirttail belonged inside his pants, but always knew when a little kid actor needed a smile and a wink or a word of encouragement". He did concede that "not everyone loved [Beery] as much as I did." Rooney noted that Howard Strickling, MGM's head of publicity, once went to Louis B. Mayer to complain that Beery was stealing props from the studio's sets. "And that wasn't all", Rooney continued. "He went on for some minutes about the trouble that Beery was always causing him ... Mayer sighed and said, 'Yes, Howard, Beery's a son of a bitch. But he's our son of a bitch.' Strickling got the point. A family has to be tolerant of its black sheep, particularly if they brought a lot of money into the family fold, which Beery certainly did."[24]

Child actors, in particular, recalled unpleasant encounters with Beery. Jackie Cooper, who made several films with him early in his career, called him "a big disappointment". Cooper accused Beery of upstaging and other attempts to undermine his performances out of what Cooper presumed was jealousy. He recalled impulsively throwing his arms around Beery after one especially heartfelt scene, only to be gruffly pushed away.[25] Child actress Margaret O'Brien claimed that she had to be protected by crew members from Beery's insistence on constantly pinching her.[26]

On another occasion, after having invited 12-year-old actor Darryl Hickman to lunch, Beery responded to Darryl's thanks with, "okay, kid, you owe me 75 cents." Beery also refused to leave tips at the MGM commissary because he explained tips are for special service, and since he was a movie star, he already got special service and therefore leaving a tip would be a waste of money.

Beery only met his match with co-star Marie Dressler. Having come up the hard and long way to her stardom, Dressler refused to take "nonsense from this baboon". She responded to one of Beery's insults by saying she would serve his head on a platter to MGM chief Louis B. Mayer. Although everyone expected Beery to explode, instead, he cowered and acted like "a little boy being very careful that Mommy didn't catch him with his hand in the cookie jar".

Future author Ray Bradbury recalled meeting Beery as a young boy on a Hollywood street, and that his autograph request resulted in Beery cursing and spitting on him.

Hobbies

Beery owned and flew his own planes,[27] one a Howard DGA-11. On April 15, 1933, he was commissioned a lieutenant commander in the United States Navy Reserve at NRAB Long Beach.[28] One of his proudest achievements was catching the largest giant black sea bass in the world — 515 pounds (234 kg) — off Santa Catalina Island in 1916, a record that stood for 35 years.[29]

Activism against National Park Lands

A noteworthy episode in Beery's life is chronicled in the fifth episode of Ken Burns' documentary The National Parks: America's Best Idea: In 1943, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed an executive order creating Jackson Hole National Monument to protect the land adjoining the Grand Tetons in Wyoming. Local ranchers, outraged at the loss of grazing lands, compared FDR's action to Hitler's taking of Austria. Led by an aging Beery, they protested by herding 500 cattle across the monument lands without a permit.[30]

Paternity suit

On February 13, 1948, Gloria Schumm (or Gloria Smith Beery, née Florence W. Smith; 1916–1989) filed a paternity suit against Beery. Beery, through his lawyer, Norman Ronald Tyre (1910–2002), initially offered $6,000 as a settlement, but denied being the father. Gloria had given birth on February 7, 1948, to Johan Richard Wallace Schumm. Gloria, in 1944, divorced Stuttgart-born Hollywood actor Hans Schumm (né Johann Josef Eugen Schumm; 1896–1990), but remarried him August 21, 1947, after realizing that she was pregnant. Prior to remarrying Schumm, Gloria, on August 4, 1947, met with Beery at his home, where he gave her the name and address of a physician to submit an examination.[31] At or around that time, she also asked Beery to marry her to "legitimatize the expected child" (her words), which Beery refused.

According to newspapers, Gloria claimed to have been intimate with Wallace Beery on or about May 1, 1947, at his home in Beverly Hills (in the court proceedings, however, she claimed to have been intimate with Beery on May 17, 1947). Beery conceded that he had known Gloria for about 15 years, and that under the pseudonym "Gloria Whitney", she had played bit roles in six films in which he starred. She again separated from Hans Schumm on April 15, 1948.

Politics

Beery supported Thomas Dewey in the 1944 United States presidential election.[32]

Death, estate, and continuing paternity suit

Beery died of a heart attack on April 15, 1949 (14 months, 1 week, and 1 day after Johan Schumm's birth) — while the suit was pending. Beery had been reading a newspaper at his Beverly Hills home when he collapsed.[33] His body was interred at Forest Lawn Memorial Park in Glendale, California. The inscription on his grave reads, "No man is indispensable, but some are irreplaceable."

Beery died intestate. In the paternity suit, Gloria Schumm's attorneys demanded $104,135 against Beery's $2,220,000 estate. In February 1952, Judge Newcomb Condee approved a $26,750 settlement from the estate. Gloria Schumm accepted the settlement, and Beery's paternity of Johan Schumm was not acknowledged.

When Mickey Rooney's father died less than a year later, Rooney arranged to have him buried next to his old friend. "I thought it was fitting that these two comedians should rest in peace, side by side", he wrote.[34]

Enduring case law

The paternity suit, and subsequent suits – including appeals – extended through about 1952 and were internationally publicized, particularly in gossip columns and tabloids. The litigation has endured as case law with, among other things, treatises addressing the rights of illegitimate offspring against legitimate heirs in races for inheritance.[35][36][37][38][39]

The upshot was that Schumm's paternity suit against Beery's estate put would-be half-siblings and other would-be family legatees, including a would-be uncle, Noah Beery Sr., in the position as de facto defendants. Phyllis Ann Riley was not named in Beery's will. Part of plaintiff's claim, initially, hinged on whether an oral agreement was binding. Gloria had claimed that Beery, while alive, agreed to provide for the child. However, on November 17, 1949, Judge William B. McKesson (1895–1967) threw out Gloria's claim. The judge reasoned that any oral agreement between the two, specifically any that was intended to provide for maintenance and care of a minor, was not binding because the amount allegedly agreed upon was in excess of $500, which must be made in writing.[40]

Another matter in the case hinged on a "peppercorn" rule. That is, for any agreement, oral or written, between Wallace and Gloria to be binding, consideration must exist. The court, initially, found that Beery agreed to an oral contract where Gloria would (i) include the name "Wallace" in the child's name if a male, or "Wally" if a female, and (ii) refrain from filing a paternity suit that both agreed would damage Beery's "social and professional standing as a prominent motion picture star".

Generally, under California state law at the time, a father who neither marries the mother nor acknowledges paternity does not have a right to name the child. That right belongs to the mother. In exchange for Gloria's promise to name the child "Wallace" or "Wally" (the promise representing a form of consideration), Wallace Beery agreed to arrange for the payment of $100 per week to the child (as a third-party beneficiary under the contract), plus a lump sum of $25,000 to the child when he or she attained age 21, in addition to the customary obligation to pay for the "maintenance, support, and education according to the station in life and standard of living of Wallace Beery".[38]

Legacy

For his contributions to the film industry, Wallace Beery posthumously received a motion-picture star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame in 1960. His star is located at 7001 Hollywood Boulevard.[2]

Beery is mentioned in the film Barton Fink, in which the lead character has been hired to write a wrestling screenplay to star Beery.[41]

In the 1971 comedy The Projectionist, actor and comedian Chuck McCann impersonates Beery, quoting a line from Min and Bill.

In the US clothing industry, a quarter-button men's shirt is called a Wallace Beery style after the undershirts and long underwear Beery's miner and outlaw characters wore beneath their outer shirt.

Selected filmography

- His Athletic Wife (1913, Short) as Mr. Strong (film debut)

- A series of at least 29 Sweedie comedy films starting with Sweedie the Swatter, released 13 July 1914

- In and Out (1914, Short) as Hans

- The Ups and Downs (1914, Short)

- Cheering a Husband (1914, Short)

- Madame Double X (1914, Short) as Madame Double X

- Two Hearts That Beat as Ten (1915, Short) (with Ben Turpin) as Fred

- Ain't It the Truth (1915, Short) as Harold Wallington

- The Slim Princess (1915) with Francis X. Bushman) as Popova

- The Broken Pledge (1915, Short) (with Gloria Swanson) as Percy

- The Fable of the Roistering Blades (1915, Short) as Milt

- A Dash of Courage (1916, Short) (with Gloria Swanson) as The Police Chief

- The Janitor's Vacation (1916)

- Patria (1917, Serial) as Pancho Villa

- Teddy at the Throttle (1917, Short) as Henry Black – Gloria's Rascally Guardian

- The Little American (1917) (with Mary Pickford) as German Soldier (uncredited)

- Maggie's First False Step (1917, Short) as The Villain

- Are Waitresses Safe? (1917) uncredited

- Johanna Enlists (1918) as Col. Fanner

- The Unpardonable Sin (1919) as Col. Klemm

- The Love Burglar (1919) (with Wallace Reid and Anna Q. Nilsson) as Coast-to-Coast Taylor

- The Life Line (1919) (with Jack Holt) as Bos

- Soldiers of Fortune (1919) as Mendoza

- Victory (1919) (with Jack Holt and Lon Chaney Sr.) as August Schomberg

- Behind the Door (1919) (with Hobart Bosworth and Jane Novak) as Lt. Brandt

- The Lone Wolf's Daughter (1919) as Minor Role (uncredited)

- The Virgin of Stamboul (1920, directed by Tod Browning) as Sheik Achmet Hamid

- The Mollycoddle (1920) (with Douglas Fairbanks) as Henry von Holkar

- The Round-Up (1920) (with Roscoe "Fatty" Arbuckle) as Buck McKee

- The Last of the Mohicans (1920) as Magua

- 813 (1920) as Maj. Parbury / Ribeira

- The Rookie's Return (1920) as François Dupont

- Patsy (1921) as Gustave Ludermann

- The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse (1921) (with Rudolph Valentino) as Lieut. Col. von Richthosen

- A Tale of Two Worlds (1921 Goldwyn)(*extant; Library of Congress) as Ling Jo

- The Golden Snare (1921) as Bram Johnson

- The Policeman and the Baby (1921, Short) (with William Desmond and Elinor Fair) as The Crook

- The Last Trail (1921) as William Kirk

- Sleeping Acres (1921, Short)

- The Rosary (1922) as Kenwood Wright

- Wild Honey (1922) (with Priscilla Dean and Noah Beery Sr.) as Buck Roper

- The Sagebrush Trail (1922) as José Fagaro

- The Man from Hell's River (1922) (with Rin Tin Tin) as Gaspard, The Wolf

- I Am the Law (1922) (with Noah Beery Sr.) as Fu Chang

- Hurricane's Gal (1922) as Chris Borg

- Trouble (1922) as Ed Lee, the Plumber

- Robin Hood (1922) (with Douglas Fairbanks) as Richard the Lion-Hearted

- A Blind Bargain (1922) (with Lon Chaney Sr.) as Beast Man (uncredited)

- Only a Shop Girl (1922) as Jim Brennan

- The Flame of Life (1923) as Don Lowrie

- Stormswept (1923) (with Noah Beery Sr.) as William McCabe

- Bavu (1923) as Felix Bavu

- Three Ages (1923) (with Buster Keaton) as The Villain

- Ashes of Vengeance (1923) (with Norma Talmadge) as Duc de Tours

- Drifting (1923) (with Priscilla Dean and Anna May Wong) as Jules Repin

- The Spanish Dancer (1923) (with Pola Negri) as King Philip IV

- The Eternal Struggle (1923) as Barode Dukane

- Richard the Lion-Hearted (1923; sequel to 1922's Robin Hood) as King Richard the Lion-Hearted

- The Drums of Jeopardy (1923) as Gregor Karlov

- White Tiger (1923, directed by Tod Browning) as Count Donelli / Hawkes

- Unseen Hands (1924) as Jean Scholast

- The Sea Hawk (1924) as Captain Jasper Leigh

- The Signal Tower (1924) as Joe Standish

- Another Man's Wife (1924) as Captain Wolf

- The Red Lily (1924) as Bo-Bo

- Dynamite Smith (1924) as 'Slugger' Rourke

- Madonna of the Streets (1924) as Bill Smythe

- So Big (1924) as Klaus Poole

- Let Women Alone (1925) as Cap Bullwinkle

- Adventure (1925) as Morgan

- The Night Club (1925) (with Raymond Griffith and Vera Reynolds) as José

- The Lost World (1925; Arthur Conan Doyle dinosaur epic in which Beery portrayed Professor Challenger) with Lewis Stone as Sir John Roxton (and Doyle himself in a frontispiece)

- The Devil's Cargo (1925) as Ben

- The Great Divide (1925) as Dutch

- Coming Through (1925) as Joe Lawler

- In the Name of Love (1925) as Glavis

- Rugged Water (1925) as Capt. Bartlett

- The Wanderer (1925) (with Greta Nissen and Tyrone Power Sr.) as Pharis

- Pony Express (1925) (with Betty Compson and George Bancroft) as Rhode Island Red

- Behind the Front (1926) (with Raymond Hatton) as Riff Swanson

- Volcano! (1926) as Quembo

- We're in the Navy Now (1926) as 'Knockout' Hansen

- Old Ironsides (1926) (with Charles Farrell and George Bancroft) as Bos'n

- Casey at the Bat (1927) (with Ford Sterling and ZaSu Pitts) as 'Home Run' Casey

- Fireman, Save My Child (1927) (with Raymond Hatton) as Elmer

- Now We're in the Air (1927) (with Louise Brooks) (only twenty minutes survive) as Wally

- Two Flaming Youths (1927) as Beery – of Beery and Hatton (uncredited)

- Wife Savers (1928, lost film) (with Raymond Hatton and ZaSu Pitts) as Louis Hosenozzle

- Partners in Crime (1928) as Detective Mike Doolan

- The Big Killing (1928) as Powderhorn Pete

- Beggars of Life (1928) (with Louise Brooks and Richard Arlen) as Oklahoma Red

- Chinatown Nights (1929) (with Warner Oland and Jack Oakie) as Chuck Riley

- Stairs of Sand (1929) as Lacey

- River of Romance (1929) as General Orlando Jackson

- The Big House (1930) (with Chester Morris, Lewis Stone, and Robert Montgomery) as Machine Gun 'Butch' Schmidt

- Billy the Kid (1930; widescreen) (with Johnny Mack Brown billed as "John Mack Brown") as Pat Garrett

- Way for a Sailor (1930) (with John Gilbert) as Tripod

- A Lady's Morals (1930) as P.T. Barnum

- Min and Bill (1930) (with Marie Dressler) as Bill

- The Stolen Jools (1931; 20-minute ensemble short) (with Edward G. Robinson and Buster Keaton) as Police Sergeant

- The Secret Six (1931) (with Jean Harlow and Clark Gable) as "Slaughterhouse" Scorpio

- The Champ (1931) (with Jackie Cooper) as Andy "Champ" Purcell (Oscar-winning performance)

- Hell Divers (1932; early military planes) (with Clark Gable) as C.P.O. H.W. "Windy" Riker

- Grand Hotel (1932) (with Greta Garbo, John Barrymore, Lionel Barrymore, and Joan Crawford) as General Director Preysing

- Flesh (1932, directed by an uncredited John Ford) as Polakai

- Tugboat Annie (1933) (with Marie Dressler, Robert Young and Maureen O'Sullivan) as Terry Brennan

- Dinner at Eight (1933) (with Marie Dressler, Lionel Barrymore, and Jean Harlow) as Dan Packard

- The Bowery (1933) (with George Raft, Jackie Cooper, Fay Wray and Pert Kelton) as Chuck Connors

- Viva Villa! (1934, shot on location in Mexico) (with Leo Carrillo, Stu Erwin and Fay Wray) as Pancho Villa

- Treasure Island (1934) (with Jackie Cooper, Lionel Barrymore and Lewis Stone) as Long John Silver

- The Mighty Barnum (1934) (with Adolphe Menjou) as P.T. Barnum

- West Point of the Air (1935) (with Robert Young, Maureen O'Sullivan, Rosalind Russell, and Robert Taylor) as Big Mike Stone

- China Seas (1935) (with Clark Gable, Jean Harlow, Lewis Stone, and Robert Benchley) as Jamesy McArdle

- O'Shaughnessy's Boy (1935) (with Jackie Cooper) as Captain Michael 'Windy' O'Shaughnessy

- Ah, Wilderness! (1935) (with Lionel Barrymore, Aline MacMahon, and Mickey Rooney) as Sid Miller

- A Message to Garcia (1936) (with Barbara Stanwyck and Alan Hale Sr.) as Sergeant Dory

- Old Hutch (1936) as 'Hutch' Hutchins

- The Good Old Soak (1937) (with Betty Furness and Ted Healy) as Clem Hawley

- Slave Ship (1937) (with Warner Baxter (first-billed) and Mickey Rooney) as Jack Thompson

- The Bad Man of Brimstone (1937) (with Noah Beery Sr.) as 'Trigger' Bill

- Port of Seven Seas (1938; written by Preston Sturges and directed by James Whale) (with Maureen O'Sullivan) as Cesar

- Stablemates (1938) (with Mickey Rooney) as Doc Thomas 'Tom' Terry

- Stand Up and Fight (1939) (with Robert Taylor and Charles Bickford) as Capt. Boss Starkey

- Sergeant Madden (1939, directed by Josef von Sternberg) (with Laraine Day) as Sgt. Shaun Madden

- Thunder Afloat (1939) (with Chester Morris) as John Thorson

- The Man from Dakota (1940) (with Dolores del Río) as Sgt. 'Bar' Barstow

- 20 Mule Team (1940) (with Anne Baxter and Noah Beery Jr.) as Skinner Bill Bragg, an Alias of Ambrose Murphy

- Wyoming (1940) (with Ann Rutherford) as 'Reb' Harkness

- The Bad Man (1941) (with Lionel Barrymore, Laraine Day, and Ronald Reagan) as Pancho Lopez

- Barnacle Bill (1941) (with Marjorie Main) as Bill Johansen

- The Bugle Sounds (1942) (with Marjorie Main, Lewis Stone, and George Bancroft) as Sgt. Patrick Aloysius 'Hap' Doan

- Jackass Mail (1942) (with Marjorie Main) as Marmaduke 'Just' Baggot

- Salute to the Marines (1943, in color) (with Noah Beery Sr.) as Sgt. Maj. William Bailey

- Rationing (1944) (with Marjorie Main) as Ben Barton

- Barbary Coast Gent (1944) (with Chill Wills and Noah Beery Sr.) as Honest Plush Brannon

- This Man's Navy (1945) (with Noah Beery Sr.) as Ned Trumpet

- Bad Bascomb (1946) (with Margaret O'Brien and Marjorie Main) as Zeb Bascomb

- The Mighty McGurk (1947) (with Dean Stockwell and Edward Arnold) as Roy 'Slag' McGurk

- Alias a Gentleman (1948) (with Gladys George and Sheldon Leonard) as Jim Breedin

- A Date with Judy (1948) (with Jane Powell, Elizabeth Taylor and Carmen Miranda) as Melvin Colner Foster

- Big Jack (1949) (with Richard Conte, Marjorie Main, and Edward Arnold) as Big Jack Horner (final film role)

Box office ranking

- 1932 – 7th

- 1933 – 5th

- 1934 – 4th

- 1935 – 8th

- 1936 – 15th, 8th (UK)

- 1937 – 15th

- 1938 – 12th

- 1939 – 15th

- 1940 – 8th

- 1941 – 19th

- 1942 – 18th

- 1943 – 18th

- 1944 – 11th

- 1946 – 11th

Behind the Door (1919) with Hobart Bosworth

Behind the Door (1919) with Hobart Bosworth The Mollycoddle (1920) with Douglas Fairbanks

The Mollycoddle (1920) with Douglas Fairbanks_-_1.jpg.webp) The Mollycoddle (1920) with Douglas Fairbanks

The Mollycoddle (1920) with Douglas Fairbanks Wallace Beery in 1921

Wallace Beery in 1921_-_1.jpg.webp) The Policeman and the Baby (1921)

The Policeman and the Baby (1921)_-_4.jpg.webp) The Golden Snare (1921)

The Golden Snare (1921) The Golden Snare (1921) with Lewis Stone

The Golden Snare (1921) with Lewis Stone_-_8.jpg.webp) The Last Trail (1921)

The Last Trail (1921) The Last Trail (1921) with Eva Novak

The Last Trail (1921) with Eva Novak A Blind Bargain (1922) with Lon Chaney

A Blind Bargain (1922) with Lon Chaney_-_2.jpg.webp) Stormswept (1923) with Noah Beery

Stormswept (1923) with Noah Beery_-_1.jpg.webp) Stormswept (1923) with Noah Beery

Stormswept (1923) with Noah Beery Stormswept (1923) with Noah Beery Sr.

Stormswept (1923) with Noah Beery Sr._-_7.jpg.webp) Bavu (1923)

Bavu (1923)_-_2.jpg.webp) Beery as Bavu (1923)

Beery as Bavu (1923) Richard the Lion-Hearted (1923)

Richard the Lion-Hearted (1923).jpg.webp) Dynamite Smith (1924) with Bessie Love

Dynamite Smith (1924) with Bessie Love_-_1.jpg.webp) Dynamite Smith (1924)

Dynamite Smith (1924) The Devil's Cargo (1925)

The Devil's Cargo (1925) Adventure (1925) with Pauline Starke

Adventure (1925) with Pauline Starke

Casey at the Bat (1927)

Casey at the Bat (1927) Now We're in the Air (1927) with Louise Brooks

Now We're in the Air (1927) with Louise Brooks Now We're in the Air (1927) with Louise Brooks

Now We're in the Air (1927) with Louise Brooks Now We're in the Air (1927) with Raymond Hatton

Now We're in the Air (1927) with Raymond Hatton Now We're in the Air (1927) with Raymond Hatton

Now We're in the Air (1927) with Raymond Hatton Beggars of Life (1928) with Louise Brooks

Beggars of Life (1928) with Louise Brooks Stairs of Sand (1929) with Jean Arthur

Stairs of Sand (1929) with Jean Arthur Min and Bill (1930) with Marie Dressler

Min and Bill (1930) with Marie Dressler

Hell Divers (1931) with Clark Gable

Hell Divers (1931) with Clark Gable Hell Divers (1931)

Hell Divers (1931) Hell Divers (1931)

Hell Divers (1931) Lionel Barrymore presents 1931 Oscar

Lionel Barrymore presents 1931 Oscar Grand Hotel (1932)

Grand Hotel (1932) Grand Hotel (1932) with Joan Crawford

Grand Hotel (1932) with Joan Crawford Tugboat Annie (1933) with Marie Dressler

Tugboat Annie (1933) with Marie Dressler Dinner at Eight (1933) with Jean Harlow

Dinner at Eight (1933) with Jean Harlow The Bowery (1933) with George Raft

The Bowery (1933) with George Raft Viva Villa! (1934) with Fay Wray

Viva Villa! (1934) with Fay Wray_01.jpg.webp) Treasure Island (1934) with Jackie Cooper

Treasure Island (1934) with Jackie Cooper Treasure Island (1934) with Jackie Cooper

Treasure Island (1934) with Jackie Cooper China Seas (1935)

China Seas (1935) China Seas (1935) with Clark Gable

China Seas (1935) with Clark Gable China Seas (1935)

China Seas (1935) Ah Wilderness! (1935)

Ah Wilderness! (1935) The Good Old Soak (1937) with Ted Healy

The Good Old Soak (1937) with Ted Healy The Bad Man of Brimstone (1937)

The Bad Man of Brimstone (1937) Stand Up and Fight (1939) with Robert Taylor

Stand Up and Fight (1939) with Robert Taylor The Man from Dakota (1940)

The Man from Dakota (1940) The Man from Dakota (1940)

The Man from Dakota (1940) 20 Mule Team (1940) with Noah Beery Jr.

20 Mule Team (1940) with Noah Beery Jr. Wyoming (1940) with Marjorie Main

Wyoming (1940) with Marjorie Main.png.webp) Barnacle Bill (1941)

Barnacle Bill (1941)

Awards and nominations

| Year | Award | Film | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1930 | Best Actor | The Big House | Nominated |

| 1932 | The Champ | Won | |

| Year | Award | Film | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1934 | Volpi Cup for Best Actor | Viva Villa! | Won |

See also

References

- ↑ Obituary Variety, April 20, 1949.

- 1 2 Walk of Fame Stars-Wallace Beery

- 1 2 Dictionary of Missouri Biography, Lawrence O. Christensen, University of Missouri Press, 1999.

- ↑ Geni.com Wallace Beery and siblings genealogy

- ↑ "The Yankee Tourist – Broadway Musical – Original | IBDB". www.ibdb.com. Archived from the original on January 31, 2021.

- 1 2 Sonneborn, Liz (May 14, 2014). A to Z of American Women in the Performing Arts. Infobase Publishing (published 2002). ISBN 9781438107905. OCLC 297504194.

- ↑ Library of Congress American Silent Feature Film Survival Database: Richard the Lion-Hearted

- ↑ Scott Eyman, Lion of Hollywood: The Life and Legend of Louis B. Mayer, Robson, 2005, p. 191 ISBN 9781861058928

- ↑ History of the Academy Awards: The Fifth Academy Awards, 1931/32. About.com archive. Retrieved April 2, 2015.

- ↑ DOUGLAS W. CHURCHILL (December 30, 1934). "THE YEAR IN HOLLYWOOD: 1984 May Be Remembered as the Beginning of the Sweetness-and-Light Era". The New York Times. p. X5.

- 1 2 The Fixers: Eddie Mannix, Howard Strickling, and the MGM Publicity Machine, by E J Fleming (né Edward J. Fleming IV; born 1954), McFarland & Company (2005); p. 176; OCLC 215262172

- 1 2 "A nyuk on the wild side: Did the Three Stooges Cover Up the Murder of Their Founder?," by Jim Mueller, Chicago Tribune, April 4, 2002 (retrieved September 3, 2017)

- ↑ The Eddie Mannix Ledger, Los Angeles: Margaret Herrick Library, Center for Motion Picture Study.

- 1 2 Shearer, Stephen Michael (2013). Gloria Swanson: The Ultimate Star. Thomas Dunne Books. ISBN 9781250013668.

- ↑ Swanson, Gloria (1980). Swanson on Swanson. Random House. pp. 69–75. ISBN 0-394-50662-6.

- ↑ Katchmer, George A. (May 8, 2002). A Biographical Dictionary of Silent Film Western Actors and Actresses. McFarland. ISBN 9781476609058.

- ↑ staff (December 23, 1937). "Wealthy Sportsman Confesses Fight with Ted Healy". The Oxnard Daily Courier. p. 1. Retrieved May 15, 2013.

- ↑ Cassara, Bill (2014). Nobody's Stooge: Ted Healy. BearManor Media. pp. 101–4. ISBN 978-1593937683.

- ↑ "Ted Healy Died of Toxic Nephritis". Lewiston Evening Journal. December 23, 1937. p. 8. Retrieved May 15, 2013.

- ↑ "Milestones," Time, December 4, 1939

- ↑ A Certain Cinema, Acertaincinema.com

- ↑ "Beery Will Add To Adopted Family". Palm Beach Post. Hollywood. UP. December 8, 1939. p. 22. Retrieved March 31, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ Eyman, S (2005). Lion of Hollywood: The Life and Legend of Louis B. Mayer. New York: Simon and Schuster. pp. 222–223. ISBN 0-7432-0481-6.

- ↑ Rooney, M. Life is Too Short. Villard Books (1991), p. 77. ISBN 0679401954.

- ↑ Bergan, R (May 5, 2011). Jackie Cooper Obituary. The Guardian archive. Retrieved August 20, 2012.

- ↑ Private Screenings: Child Stars|date=March 2009

- ↑ "Wallace Beery," (www

.dmairfield ).com - ↑ Heiser, Wayne H., "U.S. Naval and Marine Corps Reserve Aviation V. I, 1916–1942." p.78.

- ↑ "Quite a Record". The News Leader. December 18, 1977. p. 13. Retrieved March 31, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ Episode Five: 1933–1945 Great Nature

- ↑ "Links Beery to Physician". Long Beach Independent. Los Angeles. April 29, 1948. p. 12. Retrieved March 31, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ Critchlow, Donald T. (October 21, 2013). When Hollywood Was Right: How Movie Stars, Studio Moguls, and Big Business Remade American Politics. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781107650282.

- ↑ "From the Archives: Wally Beery, Veteran Film Actor, Dies". Los Angeles Times. April 17, 1949.

- ↑ Rooney, M. Life is Too Short. Villard Books (1991), p. 239. ISBN 0679401954.

- ↑ "Johan Richard Wallace Schumm, a Minor, etc., Appellant, v Phil Berg, (Beery's agent) and Noah Beery Jr. (Beery's nephew), as Executors of the Estate of Wallace Beery Jr." (opinion of Justice Jesse W. Carter), citation: 37 Cal.2d 174 (1951), Supreme Court California Resources, Stanford Law School, Robert Crown Law Library(Philip Jay Berg, 1902–1983, was married to actress Leila Hyams)

- ↑ 2 Photographs of Mrs. Gloria Schumm and son, Johann Schumm (age 4), April 17, 1952; OCLC 822257200, 857831052, 663235176

- ↑ Ardor in the Court!: Sex and the Law, by Jeffrey Miller (born 1950), ECW Press (2002); OCLC 972272320

- 1 2 "Charitable Naming Rights Transactions: Gifts or Contracts?," by William Drennan, Michigan State Law Review, Michigan State University College of Law (2016), pps. 1324–1326 (Schumm v. Berg); ISSN 1087-5468

- ↑ K: A Common Law Approach to Contracts (2nd ed.), by Tracey E. George, Russell Korobkin, Wolters Kluwer (2017), p. 32; ISBN 978-1-4548-6819-4; OCLC 951854766

- ↑ "Court Rejects Claim Beery Millions". Los Angeles Times. November 18, 1949. p. I17. Retrieved March 31, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ Rafferty, Terrence (July 27, 2003). "FILM; He's Nobody Important, Really. Just a Movie Writer". The New York Times.