| War on drugs | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

.jpg.webp) A U.S. government PSA from the Alcohol, Drug Abuse, and Mental Health Administration with a photo image of two marijuana cigarettes and a "Just Say No" slogan. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

The war on drugs is the policy of a global campaign,[1] led by the United States federal government, of drug prohibition, military aid, and military intervention, with the aim of reducing the illegal drug trade in the United States.[2][3][4][5] The initiative includes a set of drug policies that are intended to discourage the production, distribution, and consumption of psychoactive drugs that the participating governments, through United Nations treaties, have made illegal.

The term "war on drugs" was popularized by the media shortly after a press conference, given on June 17, 1971, during which President Richard Nixon declared drug abuse "public enemy number one".[6] He stated, "In order to fight and defeat this enemy, it is necessary to wage a new, all-out offensive. … This will be a worldwide offensive. … It will be government-wide … and it will be nationwide." Earlier that day, Nixon had presented a special message to Congress on Drug Abuse Prevention and Control, which included text about devoting more federal resources to the "prevention of new addicts, and the rehabilitation of those who are addicted" but that aspect did not receive the same public attention as the term "war on drugs".[7][6][8][9]

In the years since, presidential administrations have generally maintained or expanded Nixon's original initiatives, with the emphasis on law enforcement and interdiction over public health and treatment.

In June 2011, the Global Commission on Drug Policy released a critical report, declaring: "The global war on drugs has failed, with devastating consequences for individuals and societies around the world."[1] In 2015, the Drug Policy Alliance, which advocates for an end to the war on drugs, estimated that the United States spends $51 billion annually on these initiatives; in 2021, after 50 years of the drug war, others have estimated that the US has spent a cumulative $1 trillion on it.[10][11]

History

Drugs in the U.S. were largely unregulated until the early 20th century. Opium had been used to relieve pain since the American War of Independence (1775-1783), particularly in the treatment of soldiers during wartime. In the 1800s, the use of opiates in the civilian population increased dramatically,[12] and cocaine use became prevalent.[13][14] The practice of smoking cannabis spread in the early 1900s.[15]

Mid-1800s–1909: Proliferation of unregulated drug use

The latter half of the 19th century saw a ramping up of opiate and cocaine use in America. Early in the century, morphine had been isolated from opium, decades later, heroin was created from morphine, each more potent than the previous form.[16][17] With the innovation of the hypodermic syringe, opiates were easily administered and became a preferred medical treatment. During the Civil War (1861-1865), millions of doses of opiates were distributed to sick and wounded soldiers, addicting some;[12] home gardens were turned to poppies for opium processing in the war effort.[18]

In the civilian population, physicians treated opiates like a wonder drug, prescribing them widely, for chronic pain, irritable babies, asthma, bronchitis, insomnia, "nervous conditions", hysteria, menstrual cramps, morning sickness, gastrointestinal disease, "vapors", and on.[12][19][20] Cocaine appeared as a surgical anesthetic, and more popularly as a pick-me-up.[13][14]

With no federal restrictions, drugs were marketed over-the-counter to consumers. Laudanum, a powdered opium solution, was commonly found in the home medicine cabinet.[21][22] Heroin was available as a cough syrup.[23][24][25] Cocaine appeared in soft drinks, cigarettes, blended with wine, in snuff, and other forms.[13][14] Brand names were established, like Coca-Cola and Bayer Heroin.[18] In the 1890s, the Sears & Roebuck catalog, distributed to millions of American homes, offered a syringe and a small amount of cocaine or heroin for $1.50.[23][24][25]

By the end of the century, an estimated 1 in 200 Americans were addicted to opiates, 60 percent of them women, typically white and middle- to upper-class.[12] Medical journals of the later 1800s were replete with warning against overprescription. Major medical advances, like the x-ray, vaccines, and germ theory presented better treatment options, and prescribed opiate use began to decline. Meanwhile, opium smoking occurred among Chinese immigrants, who established opium dens in Chinatowns in cities and towns across America. The public face of opiate use and addiction changed, from affluent white Americans, to Chinese workers and, according to drug policy historian David T. Courtwright, “lower-class urban males", white and "often neophyte members of the underworld.”[12]

During the second half of the century, some states enacted laws banning or regulating certain drugs.[26]

1909–1971: Rise of federal drug regulation and prohibition

On February 9, 1909, Public Law No. 221, the Smoking Opium Exclusion Act, "to prohibit the importation and use of opium for other than medicinal purposes", became the first federal law to ban the non-medical use of a substance.[26][27][28] This was soon followed by the Harrison Narcotics Tax Act of 1914, that regulated and taxed the production, importation, and distribution of opiates and coca products.[29][30]

During World War I many soldiers were treated with morphine and became addicted.[12]

In 1919, the U.S. passed the 18th Amendment, prohibiting the sale, manufacture, and transportation of alcohol, with exceptions for religious and medical use, and the National Prohibition Act, informally known as the Volstead Act, to carry out the provisions in the 18th Amendment. Federal prohibition for alcohol was repealed by passage of the 21st Amendment in 1933.

The Anti-Heroin Act of 1924 made it illegal to manufacture, import or sell heroin.[16]

The Federal Bureau of Narcotics was established as an agency of the US Department of the Treasury by an act of June 14, 1930,[31] with Harry J. Anslinger as the founding commissioner, a position he held for 32 years, until 1962.[32] He supported Prohibition and the criminalization of all drugs, and spearheaded anti-drug policy campaigns.[33] According to Anslinger, opium poppy fields contained “as much potential disaster as an atom bomb”.[34] He has been characterized as an early proponent of the war on drugs, as he zealously advocated for and pursued harsh drug penalties, in particular regarding cannabis.[35]

In 1935, President Franklin D. Roosevelt publicly supported the adoption of the Uniform State Narcotic Drug Act; the New York Times used the headline "Roosevelt Asks Narcotic War Aid".[36][37]

With the passage of the Marihuana Tax Act of 1937,[38] cannabis joined opiates and cocaine as the most prohibited drugs. That year, the first two arrests for tax non-payment, for possession of a quarter-ounce (7g), and trafficking of four pounds (1.8 kg), resulted in sentences of nearly 18 months and four years respectively.[39] The American Medical Association (AMA) had opposed the tax on grounds that it unduly affected the medical use of cannabis. The AMA's legislative counsel testified that the claims about cannabis addiction, violence and overdoses were not supported.[40][41] Scholars have posited that the Act was orchestrated by powerful business interests – Andrew Mellon, Randolph Hearst, and the Du Pont family – to head off cheap competition from the hemp industry: Mellon was invested in DuPont's new synthetic plastic, nylon; Hearst was involved with pulp and timber.[42][43][44][45][46][47][48][49][50][51][52][53][Note 1]

Drugs as a growing political issue, penalties get harsher

In the early 1950s, "white suburban grassroots movements" at state level were pushing liberal politicians to crack down on drugs. California, Illinois, and New York passed the first mandatory minimums for drug offenses; Congress soon followed.[56] In 1951, Congress changed its approach to mandatory minimum penalties: their number, length, and the scope of crimes they covered all increased. According to the United States Sentencing Commission, reporting in 2012: "Before 1951, mandatory minimum penalties typically punished offenses concerning treason, murder, piracy, rape, slave trafficking, internal revenue collection, and counterfeiting. Today, the majority of convictions under statutes carrying mandatory minimum penalties relate to controlled substances, firearms, identity theft, and child sex offenses.".[57]

In 1961, 64 countries initially signed on to the United Nations' Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs, a treaty that unified all the international drug agreements then in existence.[58] In the US, the treaty was ratified and came into force in 1967.[59] The Single Convention became the first of three treaties that currently form the legal framework for international drug control.[60][61]

In 1968, President Lyndon B. Johnson (1963-1969) decided that the government needed to make an effort to curtail the social unrest that blanketed the country at the time. He decided to focus his efforts on illegal drug use, an approach that was in line with expert opinion on the subject at the time. In the 1960s, it was believed that at least half of the crime in the U.S. was drug-related, and this number grew as high as 90 percent in the next decade.[62] He created the Reorganization Plan of 1968 which merged the Bureau of Narcotics and the Bureau of Drug Abuse Control to form the Bureau of Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs within the Department of Justice.[63]

The Richard Nixon presidency (1969-1974) did not back away from the anti-drug precedent set by his predecessor. In his 1968 presidential nominee acceptance speech, Nixon pledged, "Our new Attorney General will ... launch a war against organized crime in this country. ... will be an active belligerent against the loan sharks and the numbers racketeers that rob the urban poor. ... will open a new front against the filth peddlers and the narcotics peddlers who are corrupting the lives of the children of this country."[64] In a 1969 special message to Congress, he identified drug abuse as "a serious national threat".[65][66]

On October 27, 1970, Nixon signed into law the Comprehensive Drug Abuse Prevention and Control Act of 1970. Under the Act, simple possession was reduced from a felony to a misdemeanor, the first offense carried a maximum of one year in prison, and judges had the latitude to assign probation, parole or dismissal. Penalties for trafficking were increased, up to life depending on quantity and type of drug. Funding was authorized for the Department of Health, Education and Welfare to provide treatment, rehabilitation and education. Additional federal drug agents were provided, and a "no-knock" power was instituted, that allowed entry into homes without warning to prevent evidence from being destroyed. Licensing and stricter reporting and record-keeping for drug manufacturers and distributors would occur under the Act.[67] Title II of Act, the Controlled Substances Act, established five drug Schedules, categories based on medical value and potential for abuse.[68]

1971–present: The "War on Drugs"

On May 27, 1971, after a trip to Vietnam, two congressmen, Morgan F. Murphy (Democrat) and Robert H. Steele (Republican), released a report describing a "rapid increase in heroin addiction within the United States military forces in South Vietnam". They estimated that "as many as 10 to 15 percent of our servicemen are addicted to heroin in one form or another."[69][68][70][71] On June 6, a New York Times article, "It's Always A Dead End On 'Scag Alley'", cited the Murphy-Steele report in a discussion of heroin addiction. The article stated that, in the US, "the number of addicts is estimated at 200,000 to 250,000, only about one‐tenth of 1 per cent of the population but troublesome out of all proportion." It also noted, "Heroin is not the only drug problem in the United States. 'Speed' pills—among them, amphetamines—are another problem, and not least in the suburbs where they are taken by the housewife (to cure her of the daily 'blues') and by her husband (to keep his weight down)."[72]

On June 17, 1971, Nixon presented to Congress a plan for expanded anti-drug abuse measures. He painted a dire picture: "Present efforts to control drug abuse are not sufficient in themselves. The problem has assumed the dimensions of a national emergency. ... If we cannot destroy the drug menace in America, then it will surely in time destroy us." His strategy involved both prevention and treatment: "I am proposing the appropriation of additional funds to meet the cost of rehabilitating drug users, and I will ask for additional funds to increase our enforcement efforts to further tighten the noose around the necks of drug peddlers, and thereby loosen the noose around the necks of drug users." He singled out heroin and broadened the scope beyond the US: "To wage an effective war against heroin addiction, we must have international cooperation. In order to secure such cooperation, I am initiating a worldwide escalation in our existing programs for the control of narcotics traffic."[73]

Later the same day, Nixon held a news conference at the White House, where he described increasing drug use in the US as "public enemy number one." He announced, "In order to fight and defeat this enemy, it is necessary to wage a new, all-out offensive. … This will be a worldwide offensive. … It will be government-wide … and it will be nationwide." Nixon pledged to ask Congress for a minimum of $350 million for the anti-drug effort (when he took office in 1969, the federal drug budget was $81 million).[74]

Nixon began orchestrating drug raids nationwide to improve his "watchdog" reputation. Lois B. Defleur, a social historian who studied drug arrests during this period in Chicago, stated that, "police administrators indicated they were making the kind of arrests the public wanted". Additionally, some of Nixon's newly created drug enforcement agencies would resort to illegal practices to make arrests as they tried to meet public demand for arrest numbers. From 1972 to 1973, the Office of Drug Abuse and Law Enforcement performed 6,000 drug arrests in 18 months, the majority of the arrested black.[75]

In 1973, the Drug Enforcement Administration was created to replace the Bureau of Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs.[68] The Nixon administration also repealed the federal 2 to 10-year mandatory minimum sentences for possession of marijuana and started federal demand reduction programs and drug-treatment programs. Robert DuPont, the "drug czar" in the Nixon Administration, stated it would be more accurate to say that Nixon ended, rather than launched, the "war on drugs". DuPont also argued that it was the proponents of drug legalization that popularized the term "war on drugs".[76]

Decades later, a controversial quote attributed to John Ehrlichman, Nixon's domestic policy advisor, claimed that the war on drugs was fabricated to undermine the anti-war movement and African Americans. In a 2016 Harper's cover story, journalist Dan Baum quoted Ehrlichman from unearthed notes of a 1994 interview: "... by getting the public to associate the hippies with marijuana and blacks with heroin, and then criminalizing both heavily, we could disrupt those communities. We could arrest their leaders, raid their homes, break up their meetings, and vilify them night after night on the evening news. Did we know we were lying about the drugs? Of course we did."[77][78][79][80] Ehrlichman died in 1999.[81] His family challenged the "alleged 'quote'" outright,[82] as did three Nixon senior White House officials in a written statement.[83] An investigative article in Vox concluded that "Ehrlichman's claim is likely an oversimplification", if not a lie. In the end, it was the progressive reshaping of US drug policy by later administrations that became most responsible for creating conditions such as Ehrlichman described.[84]

The war on drugs under the next two presidents, Gerald Ford (1974-1977) and Jimmy Carter (1977-1981), was essentially a continuation of their predecessors' policies. Carter's campaign platform included decriminalization of cannabis and an end to federal penalties for possession of up to one ounce.[65] In a 1977 "Drug Abuse Message to the Congress", Carter stated, "Penalties against possession of a drug should not be more damaging to an individual than the use of the drug itself." None of his advocacy was translated into law.[85][86]

Reagan escalation, crack crackdown, and "Just Say No"

The presidency of Ronald Reagan (1981-1989) saw an expansion in the federal focus of preventing drug abuse and for prosecuting offenders. Shortly after his inauguration in 1981, Reagan announced, "We're taking down the surrender flag that has flown over so many drug efforts; we're running up a battle flag."[87] From 1980 to 1984, the federal annual budget of the FBI's drug enforcement units went from 8 million to 95 million.[88][89] In 1982, Vice President George H. W. Bush and his aides began pushing for the involvement of the CIA and U.S. military in drug interdiction efforts.[90]

Early in the Reagan term, First Lady Nancy Reagan, with the help of an advertising agency, began her "Just Say No" youth anti-drug campaign. Propelled by the First Lady's tireless promotional efforts through the 1980s, "Just Say No" became firmly fixed in American pop culture. Later research found that the campaign had little or no impact on youth drug use.[91][92][93]

In 1984, Reagan signed the Comprehensive Crime Control Act, which expanded penalties for cannabis possession, and established a federal system of mandatory minimum sentences, and new procedures for civil asset forfeiture that created equitable sharing, allowing state and local law enforcement to share the proceeds from seizures made in collaboration with federal agencies.[94][95]

The Reagan administration began shoring up public opinion against crack cocaine, encouraging DEA official Robert Putnam to play up the harmful effects of the drug. Stories of "crack whores" and "crack babies" became commonplace.[96] According to historian Elizabeth Hinton, "[Reagan] led Congress in criminalizing drug users, especially African American drug users, by concentrating and stiffening penalties for the possession of the crystalline rock form of cocaine, known as 'crack', rather than the crystallized methamphetamine that White House officials recognized was as much of a problem among low-income white Americans".[97]

In the summer of 1986, crack dominating the news. Time declared crack the issue of the year.[96] Newsweek compared the magnitude of the crack story to Vietnam and Watergate.[98] The cocaine overdose deaths of rising basketball star Len Bias, and young NFL football player Don Rogers,[99] both in June, received wide coverage.[98] Riding the wave of public fervor, Reagan established much harsher sentencing for crack cocaine through the Anti-Drug Abuse Act, passed that fall, handing down stiffer felony penalties for much smaller amounts of the drug.[100] The legislation appropriated an additional $1.7 billion to fund the war on drugs. More importantly, it established 29 new, mandatory minimum sentences for drug offenses. In the entire history of the country up until that point, the legal system had only seen 55 minimum sentences in total.[101]

A major stipulation of the new sentencing rules was a hundredfold difference in mandatory minimum sentences for crack and powder cocaine. With the 100:1 ratio, conviction in federal court of possession of 5 grams of crack would receive the same mandatory minimum of 5 years in federal prison as possession of 500 grams of powder cocaine.[102][103] At the time of the bill, there was public debate as to the difference in potency and effect of powder cocaine, generally used by whites, and crack cocaine, generally used by blacks, with many believing that crack was substantially more powerful and addictive. Crack and powder cocaine are closely related chemicals, crack being a smokable, freebase form of powdered cocaine hydrochloride which produces a shorter, more intense high while using less of the drug. This method is more cost-effective, and therefore more prevalent on the inner-city streets, while powder cocaine remains more popular in white suburbia.[96]

Support for Reagan's crime legislation was bipartisan. According to Hinton, Democrats supported his legislation as they had since the Johnson administration,[97] though Reagan was a Republican.

Hard line maintained

Next to occupy the Oval Office, Reagan protégé and former Vice-president George H. W. Bush (1989-1993) maintained the hard line drawn by his predecessor and former boss. He went as far as making a speech while holding a plastic bag of crack, claiming it was seized by the DEA right across from the White House in Lafayette Park (turned out that agents had to lure the seller to the park to make the requested arrest).[104] The administration increased narcotics regulation when the first National Drug Control Strategy was issued by the Office of National Drug Control Policy (ONDCP) in 1989.[105] The director of ONDCP is became commonly known as the US drug czar,[68]

As president, Bill Clinton (1993-2001) dramatically raised the stakes for drug felonies, with his signing of the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994. The Act introduced the federal "three-strikes" provision that mandated life imprisonment for violent offenders with two prior convictions for violent crimes or drugs, and provided billions of dollars of funding for states to expand their prison systems and increase law enforcement.[106] During this period, states initiated controversial drug legislation, policies that demonstrated racial biases such as the "stop and frisk" police practices in New York City and the "three strikes" felony laws which began California in 1994.[107]

The George W. Bush (2001-2009) administration maintained the hard line approach.[108] In a TV interview in February 2001, Bush's new Attorney General, John Ashcroft, said about the war on drugs, "I want to renew it. I want to refresh it, relaunch it if you will."[109]

Growing dissent

In the summer of 2001, a report by the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), "The Drug War is the New Jim Crow", tied the vastly disproportionate rate of African American incarceration to the range of rights lost once convicted. It stated that, while "whites and blacks use drugs at almost exactly the same rates ... African-Americans are admitted to state prisons at a rate that is 13.4 times greater than whites, a disparity driven largely by the grossly racial targeting of drug laws." Between federal and state laws, those convicted of even simple possession could lose the right to vote, eligibility for educational assistance including loans and work-study programs, custody of their children, and personal property including homes. The report concluded that the cumulative affect of the war on drugs amounted to "the US apartheid, the new Jim Crow".[109] This view was further developed by lawyer and civil rights advocate Michelle Alexander in her 2010 book, The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness.[113]

During his time in office, Barack Obama (2009-2017) implemented a "tough but smart" approach to the war on drugs. While he claimed that his method differed from those of previous presidents, in reality, his practices were similar.[114] On May 13, 2009, Gil Kerlikowske, Director of the ONDCP – Obama's drug czar – indicated that the Obama administration did not plan to significantly alter drug enforcement policy, but that it would not use the term "War on Drugs". Kerlikowske considered the term to be "counter-productive".[115] In August 2010, Obama signed the Fair Sentencing Act into law, reducing the 100:1 sentencing disparity between crack and powder cocaine to 18:1.[116][117]

In 2011, an international non-governmental group, the Global Commission on Drug Policy, composed primarily of former heads of state and government, released a report that stated, "The global war on drugs has failed." It recommended a paradigm shift, to a public health focus, with decriminalization for possession and personal use.[118] Obama's ONDCP did not support the report, stating: "Drug addiction is a disease that can be successfully prevented and treated. Making drugs more available ... will make it harder to keep our communities healthy and safe."[76] US Surgeon General Regina Benjamin also released the first-ever National Prevention Strategy, a framework for preventing drug abuse and promoting healthy, active lifestyles.[119]

In May 2012, the ONDCP published an updated version of its drug policy.[120] According to the ONDCP director, drug legalization is not the "silver bullet" solution to drug control, and success is not measured by the number of arrests made or prisons built.[121] A declaration was signed by the representatives of Italy, the Russian Federation, Sweden, the UK and the US: "Our approach must be a balanced one, combining effective enforcement to restrict the supply of drugs, with efforts to reduce demand and build recovery; supporting people to live a life free of addiction."[122] Meanwhile, at the state level, 2012 saw Colorado and Washington become the first two states to legalize the recreational use of cannabis with the passage of Amendment 64 and Initiative 502.[123]

A 2013 ACLU report declared the anti-marijuana crusade a "war on people of color". The report found that "African Americans [were] 3.73 times more likely than whites to be apprehended despite nearly identical usage rates, and marijuana violations accounting for more than half of drug arrests nationwide during the previous decade".[114] Under Obama's policies, nonwhite drug offenders received less excessive criminal sanctions, but by examining criminals as strictly violent or nonviolent, mass incarceration persisted.[114]

In March 2016 the International Narcotics Control Board stated that the UN's international drug treaties do not mandate a "war on drugs" and that the choice is not between "'militarized' drug law enforcement on one hand and the legalization of non-medical use of drugs on the other", health and welfare should be the focus of drug policy[124]

Under President Donald Trump (2017-2021), Attorney General Jeff Sessions reversed his predecessor's drug position, and instructed federal prosecutors to “charge and pursue the most serious, readily provable offense” in drug cases, regardless of whether mandatory minimum sentences applied. This amounted to encouraging prison time even for simple cannabis possession.[125][126] With cannabis legalized to some degree in nearly 30 states, Sessions' directive was seen by both Democrats and Republicans as a rogue throwback action, and there was a bipartisan outcry. Trump fired Sessions in 2018, over other issues.[127]

In 2020, both the ACLU and The New York Times reported that Republicans and Democrats were in agreement that it was time to end the war on drugs. While on the presidential campaign trail, President Joe Biden (2020-current) claimed that he would take the steps to alleviate the drug war and end the opioid epidemic.[128][129]

Some partial policy reversal attempts and successes

On December 4, 2020, under the Biden administration, the United States House of Representatives passed a marijuana reform bill, the Marijuana Opportunity Reinvestment and Expungement Act (also known as the MORE Act), which decriminalized marijuana. Additionally, according to the ACLU, it "expunges past convictions and arrests, and taxes marijuana to reinvest in communities targeted by the war on drugs".[128] However, cannabis would remain a Schedule I drug under the Controlled Substances Act,[130] creating a conflict in federal law.[131] The MORE Act was received in the Senate in December 2020 where it remained.[132]

Over time, states in the US have approached drug liberalization at a varying pace. As of December 2020, Oregon became the first state to decriminalize all drugs, shifting from a criminal approach to a public health approach.[128] As of September 2023, over 30 states had decriminalized cannabis to some degree, split about equally between recreational and medical-only use. Decriminalization in this context usually refers to first-time offenses and small quantities, such as, in the case of cannabis, under an ounce (28g).[133]

In 2022, the Medical Marijuana and Cannabidiol Research Expansion Act was signed into law to allow cannabis to be more easily researched for medical purposes. It is the first standalone cannabis reform bill enacted at the federal level.[134][135][136]

In 2023, the US State Department announced plans to launch a "global coalition to address synthetic drug threats", with more than 80 countries expected to join.[137][138][139] That April, Anne Milgram, head of the DEA since 2021, stated to Congress that two Mexican drug cartels posed "the greatest criminal threat the United States has ever faced." Supporting a DEA budget request of $3.7 billion for 2024, Milgram cited fentanyl in the "most devastating drug crisis in our nation’s history."[140][141]

Foreign intervention

During the 1970s, the US treated drugs as a policing issue. Billions of dollars were given to support anti-drug activity by police forces in Latin American countries, including Colombia, Peru and Bolivia. Beginning in the 1980s, the US increasingly involved the military and private security firms, to provide training and support to armed forces in drug-producing and transit countries.[147]

Some scholars have claimed that the phrase "War on Drugs" is propaganda cloaking an extension of earlier military or paramilitary operations.[5] Others have argued that large amounts of "drug war" foreign aid money, training, and equipment actually goes to fighting leftist insurgencies and is often provided to groups who themselves are involved in large-scale narco-trafficking, such as corrupt members of the Colombian military.[4]

Latin America

At a meeting in Guatemala in 2012, three former presidents from Guatemala, Mexico and Colombia said that the war on drugs had failed and that they would propose a discussion on alternatives, including decriminalization, at the Summit of the Americas in April of that year.[148] Guatemalan President Otto Pérez Molina said that the war on drugs was exacting too high a price on the lives of Central Americans and that it was time to "end the taboo on discussing decriminalization".[149] At the summit, the government of Colombia pushed for the most far-reaching change to drugs policy since the war on narcotics was declared by Nixon four decades prior, citing the catastrophic effects it had had in Colombia.[150]

In 2021, Gustavo Gorriti, journalist and founder of IDL-Reporteros, investigating corruption in Peru, wrote a scathing editorial in the Washington Post on the impact of 50 years of the war on drugs on Latin America. He described the flow of drugs to the US as an "unstoppable industry" that triggered an economic revolution throughout the region, where the illegal drug trade with its high profit margins far exceeded the potential of legitimate businesses. Corruption among politicians and anti-drug forces soared, even as those in charge were "cultivating close relationships with U.S. enforcement and intelligence agencies." An underclass of poor farmers became economic hostages, depending on drug crops for their survival. The big winners were "the systems built to wage a fight that they soon realized would have no end. ... [The war on drugs] became a source for endless resources, inflated budgets, contracts, purchase orders, power, influence — new economies battling drug trafficking but also dependent on it."[151]

Mérida Initiative

The Mérida Initiative is a security cooperation between the United States and the government of Mexico and the countries of Central America. It was approved on June 30, 2008, and its stated aim is combating the threats of drug trafficking and transnational crime. The Mérida Initiative appropriated $1.4 billion in a three-year commitment (2008–2010) to the Mexican government for military and law enforcement training and equipment, as well as technical advice and training to strengthen the national justice systems. The Mérida Initiative targeted many very important government officials, but it failed to address the thousands of Central Americans who had to flee their countries due to the danger they faced every day because of the war on drugs. There is still not any type of plan that addresses these people. No weapons are included in the plan.[152][153]

Colombia

Through the Plan Colombia program, between 2000 and 2015, the US provided Colombia with $10 billion in funding,[154] primarily for military aid, training, and equipment,[155] to fight left-wing guerrillas such as the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC-EP), which has been accused of being involved in drug trafficking.[156]

Private U.S. corporations have signed contracts to carry out anti-drug initiatives as part of Plan Colombia. DynCorp, the largest private company involved, was among those contracted by the State Department, while others signed contracts with the Defense Department.[157]

Colombian military personnel have received extensive counterinsurgency training from U.S. military and law enforcement agencies, including the School of Americas (SOA). Author Grace Livingstone has stated that more Colombian SOA graduates have been implicated in human rights abuses than currently known SOA graduates from any other country. All of the commanders of the brigades highlighted in a 2001 Human Rights Watch report on Colombia were graduates of the SOA, including the III brigade in Valle del Cauca, where the 2001 Alto Naya Massacre occurred. US-trained officers have been accused of being directly or indirectly involved in many massacres during the 1990s, including the Trujillo Massacre and the 1997 Mapiripán Massacre.

In 2000, the Clinton administration initially waived all but one of the human rights conditions attached to Plan Colombia, considering such aid as crucial to national security at the time.[158]

The efforts of U.S. and Colombian governments have been criticized for focusing on fighting leftist guerrillas in southern regions without applying enough pressure on right-wing paramilitaries and continuing drug smuggling operations in the north of the country.[159][160] Human Rights Watch, congressional committees and other entities have documented the existence of connections between members of the Colombian military and the AUC, which the U.S. government has listed as a terrorist group, and that Colombian military personnel have committed human rights abuses which would make them ineligible for U.S. aid under current laws.

In 2010, the Washington Office on Latin America concluded that both Plan Colombia and the Colombian government's security strategy "came at a high cost in lives and resources, only did part of the job, are yielding diminishing returns and have left important institutions weaker."[161]

A 2014 report by the RAND Corporation, which was issued to analyze viable strategies for the Mexican drug war considering successes experienced in Colombia, noted:

Between 1999 and 2002, the United States gave Colombia $2.04 billion in aid, 81 percent of which was for military purposes, placing Colombia just below Israel and Egypt among the largest recipients of U.S. military assistance. Colombia increased its defense spending from 3.2 percent of gross domestic product (GDP) in 2000 to 4.19 percent in 2005. Overall, the results were extremely positive. Greater spending on infrastructure and social programs helped the Colombian government increase its political legitimacy, while improved security forces were better able to consolidate control over large swaths of the country previously overrun by insurgents and drug cartels.

It also notes that, "Plan Colombia has been widely hailed as a success, and some analysts believe that, by 2010, Colombian security forces had finally gained the upper hand once and for all."[162]

Mexico

Mexican citizens, unlike American citizens, support the current measures their government is taking against drug cartels in the War on Drugs. A Pew Research Center poll in 2010 found that 80 percent supported the current use of the army in the War on Drugs to combat drug traffickers with about 55 percent saying that they have been making progress in the war.[163] A year later in 2011 a Pew Research Center poll uncovered that 71 percent of Mexicans find that "illegal drugs are a very big problem in their country". 77 percent of Mexicans also found that drug cartels and the violence associated with them are as well a big challenge for Mexico.[164]

In 2013 a Pew Research Center poll found that 74 percent of Mexican citizens would support the training of their police and military, the poll also found that another 55 percent would support the supplying of weapons and financial aid. Though the poll indicates a support of U.S. aid, 59 percent were against troops on the ground by the U.S. military.[165] Also in 2013 Pew Research Center found in a poll that 56 percent of Mexican citizens believe that the United States and Mexico are both to blame for drug violence in Mexico. In that same poll, 20 percent believe that the United States is solely to blame and 17 percent believe that Mexico is solely to blame.[166]

One of the first anti-drug efforts in the realm of foreign policy was President Nixon's Operation Intercept, announced in September 1969, targeted at reducing the amount of cannabis entering the United States from Mexico. The effort began with an intense inspection crackdown that resulted in an almost shutdown of cross-border traffic.[167] Because the burden on border crossings was controversial in border states, the effort only lasted twenty days.[168]

Nicaragua

Senator John Kerry's 1988 U.S. Senate Committee on Foreign Relations report on Contra drug links concludes that members of the U.S. State Department "who provided support for the Contras are involved in drug trafficking... and elements of the Contras themselves knowingly receive financial and material assistance from drug traffickers."[169] The report further states that "the Contra drug links include... payments to drug traffickers by the U.S. State Department of funds authorized by the Congress for humanitarian assistance to the Contras, in some cases after the traffickers had been indicted by federal law enforcement agencies on drug charges, in others while traffickers were under active investigation by these same agencies."

Panama

On December 20, 1989, the United States invaded Panama as part of Operation Just Cause, which involved 25,000 American troops. Gen. Manuel Noriega, head of the government of Panama, had been giving military assistance to Contra groups in Nicaragua at the request of the U.S. which, in exchange, tolerated his drug trafficking activities, which they had known about since the 1960s.[170][171] When the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) tried to indict Noriega in 1971, the CIA prevented them from doing so.[170] The CIA, which was then directed by future president George H. W. Bush, provided Noriega with hundreds of thousands of dollars per year as payment for his work in Latin America.[170] When CIA pilot Eugene Hasenfus was shot down over Nicaragua by the Sandinistas, documents aboard the plane revealed many of the CIA's activities in Latin America, and the CIA's connections with Noriega became a public relations "liability" for the U.S. government, which finally allowed the DEA to indict him for drug trafficking, after decades of tolerating his drug operations.[170] Operation Just Cause and Nifty Package were launched to capture Noriega and overthrow his government; although Noriega found temporary asylum in the Papal Nuncio, he surrendered to U.S. soldiers on January 3, 1990.[172] He was sentenced by a court in Miami to 45 years in prison.[170]

Honduras

In 2012, the U.S. sent DEA agents to Honduras to assist security forces in counternarcotics operations. Honduras has been a major stop for drug traffickers, who use small planes and landing strips hidden throughout the country to transport drugs. The U.S. government made agreements with several Latin American countries to share intelligence and resources to counter the drug trade. DEA agents, working with other U.S. agencies such as the State Department, the CBP, and Joint Task Force-Bravo, assisted Honduras troops in conducting raids on traffickers' sites of operation.[173]

Aerial herbicide application

The United States regularly sponsors the spraying of large amounts of herbicides such as glyphosate over the jungles of Central and South America as part of its drug eradication programs. Environmental consequences resulting from aerial fumigation have been criticized as detrimental to some of the world's most fragile ecosystems;[174] the same aerial fumigation practices are further credited with causing health problems in local populations.[175]

Impact on growers

The status of coca and coca growers has become an intense political issue in several countries, including Colombia and particularly Bolivia, where former president Evo Morales, a former coca growers' union leader, promised to legalise the traditional cultivation and use of coca.[176] Indeed, legalization efforts yielded some successes under the Morales administration when combined with aggressive and targeted eradication efforts. The country saw a 12–13% decline in coca cultivation[176] in 2011 under Morales, who used coca growers' federations to ensure compliance with the law rather than providing a primary role for security forces.[176]

The coca eradication policy has been criticised for its negative impact on the livelihood of coca growers in South America. In many areas of South America the coca leaf has traditionally been chewed and used in tea and for religious, medicinal and nutritional purposes by locals.[177] For this reason many insist that the illegality of traditional coca cultivation is unjust. In many areas the U.S. government and military has forced the eradication of coca without providing for any meaningful alternative crop for farmers, and has additionally destroyed many of their food or market crops, leaving them starving and destitute.[177]

Domestic impact

The social consequences of the drug war have been widely criticized by such organizations as the ACLU as being racially biased against minorities and disproportionately responsible for the exploding United States prison population. According to a report commissioned by the Drug Policy Alliance, and released in March 2006 by the Justice Policy Institute, America's "Drug-Free Zones" are ineffective at keeping youths away from drugs, and instead create strong racial disparities in the judicial system.[178]

Several critics have compared the wholesale incarceration of the dissenting minority of drug users to the wholesale incarceration of other minorities in history. Psychiatrist Thomas Szasz, for example, wrote in 1997 "Over the past thirty years, we have replaced the medical-political persecution of illegal sex users ('perverts' and 'psychopaths') with the even more ferocious medical-political persecution of illegal drug users."[179]

Incarceration

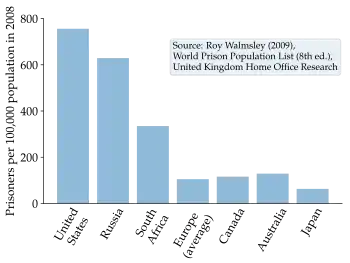

According to Human Rights Watch, the War on Drugs caused soaring arrest rates that disproportionately targeted African Americans due to various factors.[180] Anti-drug and tough-on-crime policies from the 1970s through the 1990s created a situation where the US, with less than 5% of the world population, houses nearly 25% of the world's prisoners. As of 2015, the US prison population rate was 716 per 100,000 people, the highest in the world, six times higher than Canada and six to nine times higher than Western European countries.[181]

After 1980, the situation began to change. In the 1980s, while the number of arrests for all crimes had risen by 28%, the number of arrests for drug offenses rose 126%.[182] The result of increased demand was the development of privatization and the for-profit prison industry.[183] The Department of Justice, reporting on the effects of state initiatives, has stated that, from 1990 through 2000, "the increasing number of drug offenses accounted for 27% of the total growth among black inmates, 7% of the total growth among Hispanic inmates, and 15% of the growth among white inmates." In addition to prison or jail, the United States provides for the deportation of many non-citizens convicted of drug offenses.[184]

In 1994, the New England Journal of Medicine reported that the "War on Drugs" resulted in the incarceration of one million Americans each year.[185] In 2008, The Washington Post reported that of 1.5 million Americans arrested each year for drug offenses, half a million would be incarcerated.[186] In addition, one in five black Americans would spend time behind bars due to drug laws.[186]

Federal and state policies also impose collateral consequences on those convicted of drug offenses, separate from fines and prison time, that are not applicable to other types of crime.[187] For example, a number of states have enacted laws to suspend for six months the driver's license of anyone convicted of a drug offense; these laws were enacted in order to comply with a federal law known as the Solomon–Lautenberg amendment, which threatened to penalize states that did not implement the policy.[188][189][190] Other examples of collateral consequences for drug offenses, or for felony offenses in general, include loss of professional license, loss of ability to purchase a firearm, loss of eligibility for food stamps, loss of eligibility for Federal Student Aid, loss of eligibility to live in public housing, loss of ability to vote, and deportation.[187]

Prison overcrowding

One consequence of the war on drugs policy has been the overcrowding of prisons within the United States. The policy's approach to prosecuting drug-related offenses has led to a surge in incarcerated individuals for nonviolent drug offenses. As a result, many prisons have become overburdened, often operating at capacities far beyond their intended limits. Overcrowding not only strains the prison system itself but also raises questions about the effectiveness of incarceration as a solution to drug-related issues.[191] Resources that could be allocated to address the root causes of drug abuse, provide rehabilitation and treatment programs, or support communities affected by drug-related issues are instead diverted to managing the burgeoning prison population. This reallocation of resources away from preventive measures and treatment options undermines the potential for a comprehensive and holistic approach to addressing drug-related challenges. Critics argue that focusing solely on incarceration fails to address the underlying social factors contributing to drug abuse and perpetuates a cycle of criminality without offering pathways to recovery and reintegration into society.[192]

Racial disparities in sentencing

Racial disparities have been a prominent and contentious aspect of the "War on Drugs" in the U.S. In 1957, the belief at the time about drug use was summarized by journalist Max Lerner in his work, America as a Civilization:

As a case in point we may take the known fact of the prevalence of reefer and dope addiction in Negro areas. This is essentially explained in terms of poverty, slum living, and broken families, yet it would be easy to show the lack of drug addiction among other ethnic groups where the same conditions apply.

The Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1986 created a 100 to 1 sentencing disparity in the U.S. for the trafficking or possession of crack when compared to penalties for trafficking of powder cocaine.[193][102][103][194] The bill had been widely criticized as discriminatory against minorities, mostly blacks, who were more likely to use crack than powder cocaine.[195] In 1994, studying the effects of the 100:1 sentencing ratio, the United States Sentencing Commission (USSC) found that nearly two-thirds of crack users were white or Hispanic, while nearly 85% of those convicted for possession were black, with similar numbers for trafficking. Powder cocaine offenders were more equally divided across race. The USSC noted that these disparities resulted in African Americans serving longer prison sentences than other ethnicities. In a 1995 report to Congress, the USSC recommended against the 100:1 sentencing ratio.[196][197] In 2010, the 100:1 sentencing ratio was reduced to 18:1.[195][198]

Other studies indicated similarly dramatic racial differences in enforcement and sentencing. Statistics from 1998 show that there were wide racial disparities in arrests, prosecutions, sentencing and deaths. African-American drug users made up for 35% of drug arrests, 55% of convictions, and 74% of people sent to prison for drug possession crimes.[102] Nationwide African-Americans were sent to state prisons for drug offenses 13 times more often than other races,[199] even though they supposedly constituted only 13% of regular drug users.[102] Human Rights Watch's report, "Race and the Drug War" (2000), provided extensive documentation of racial disparities in drug law enforcement. The report presented statistics and case studies highlighting the unequal treatment of racial and ethnic groups by law enforcement agencies, particularly in drug arrests.[200] According to the report, in the US in 1999, compared to non-minorities, African Americans were far more likely to be arrested for drug crimes, and received much stiffer penalties and sentences.[201]

In Malign Neglect – Race Crime and Punishment in America (1995), University of Minnesota professor and social justice author Michael Tonry wrote, "The War on Drugs foreseeably and unnecessarily blighted the lives of hundreds and thousands of young disadvantaged black Americans and undermined decades of effort to improve the life chances of members of the urban black underclass."[202]

In her 2010 book, The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness, Michelle Alexander underscored the profound impact of drug policies on minority communities. The book argues that the "War on Drugs" has effectively perpetuated a racial caste system, with African American and Hispanic individuals experiencing disproportionately high rates of arrest, conviction, and incarceration for drug-related offenses. Alexander contends that this system functions as a modern form of racial control, stripping individuals of their rights and opportunities, and reinforcing societal inequalities.[203] The consequences of these racial disparities extend beyond criminal justice, affecting economic opportunities, access to education, and overall social mobility for affected individuals and communities.[203] As such, discussions around racial disparities in the "War on Drugs" have played a pivotal role in shaping public discourse and policy reform efforts aimed at addressing these issues.[200]

Public opinion

In the 21st century, according to polling, a majority of Americans have been skeptical about the methods and effectiveness of the war on drugs. A national poll in 2008 found that three in four Americans believed that the drug war was failing.[204] In 2014, a Pew Research Center poll found found that 67% of Americans feel that a movement towards treatment for drugs like cocaine and heroin is better versus 26% who feel that prosecution is the better route. Moving away from mandatory prison terms for drug crimes was favored by two-thirds of the population, a substantial shift from a fifty-fifty for-against split in 2001. A large majority saw alcohol as a greater danger to health (69%) and society (63%) than cannabis.[205][206] In 2018, a Rasmussen Reports poll found that less than 10% of Americans think that the war on drugs is being won.[207]

Socioeconomic effects

Permanent underclass creation

Penalties for drug crimes among American youth almost always involve permanent or semi-permanent removal from opportunities for education, strip them of voting rights, and later involve creation of criminal records which make employment more difficult. One-fifth of the US prison population are incarcerated for a drug offence.[208] Thus, some authors maintain that the War on Drugs has resulted in the creation of a permanent underclass of people who have few educational or job opportunities, often as a result of being punished for drug offenses which in turn have resulted from attempts to earn a living in spite of having no education or job opportunities.[209][210]

Costs to taxpayers

According to a 2008 study published by Harvard economist Jeffrey A. Miron, the annual savings on enforcement and incarceration costs from the legalization of drugs would amount to roughly $41.3 billion, with $25.7 billion being saved among the states and over $15.6 billion accrued for the federal government. Miron further estimated at least $46.7 billion in tax revenue based on rates comparable to those on tobacco and alcohol: $8.7 billion from marijuana, $32.6 billion from cocaine and heroin, and $5.4 billion from other drugs.[211]

Low taxation in Central American countries has been credited with weakening the region's response in dealing with drug traffickers. Many cartels, especially Los Zetas have taken advantage of the limited resources of these nations. 2010 tax revenue in El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras, composed just 13.53% of GDP. As a comparison, in Chile and the U.S., taxes were 18.6% and 26.9% of GDP respectively. However, direct taxes on income are very hard to enforce and in some cases tax evasion is seen as a national pastime.[212]

Impact on employment

Critics note that the War on Drugs also creates an artificial shortage of workers in the labor force due to random drug testing. For example, according to the Department of Transportation, in 2020, 70,000 truck drivers were fired due to testing positive for cannabis use.[213] This is during a period in which 70% of Americans claim to experience product shortages and delays.[214] Additionally, the American Trucking Associations claims that the trucking industry is short 80,000 truck drivers, a number that could potentially double by 2030.[215] Furthermore, the Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration increased the amount of random drug tests from 25% of the average number of driver positions to 50%, which, critics note, will result in an even greater amount of truck driver and supply shortages.[216]

Legality

The legality of drug prohibition within the US has been challenged on various grounds. One argument holds that drug prohibition, as presently implemented, violates the substantive due process doctrine in that its benefits do not justify the encroachments on rights that are supposed to be guaranteed by the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments to the U.S. Constitution.[217][218] Another argument interprets the Commerce Clause to mean that drugs should be regulated in state law not federal law. A third argument states that the reverse burden of proof in drug-possession cases is incompatible with the rule of law, in that the power to convict is effectively taken from the courts and given to those who are willing to plant evidence.[219]

Efficacy

The National Research Council Committee on Data and Research for Policy on Illegal Drugs published its findings in 2001 on the efficacy of the drug war. The NRC Committee found that existing studies on efforts to address drug usage and smuggling, from U.S. military operations to eradicate coca fields in Colombia, to domestic drug treatment centers, have all been inconclusive, if the programs have been evaluated at all: "The existing drug-use monitoring systems are strikingly inadequate to support the full range of policy decisions that the nation must make.... It is unconscionable for this country to continue to carry out a public policy of this magnitude and cost without any way of knowing whether and to what extent it is having the desired effect."[220] The study, though not ignored by the press, was ignored by top-level policymakers, leading Committee Chair Charles Manski to conclude, as one observer notes, that "the drug war has no interest in its own results".[221]

| External videos | |

|---|---|

In 1986, the US Defense Department funded a two-year study by the RAND Corporation, which found that the use of the armed forces to interdict drugs coming into the United States would have little or no effect on cocaine traffic and might, in fact, raise the profits of cocaine cartels and manufacturers. The 175-page study, Sealing the Borders: The Effects of Increased Military Participation in Drug Interdiction, was prepared by seven researchers, mathematicians and economists at the National Defense Research Institute, a branch of the RAND, and was released in 1988. The study noted that seven prior studies in the past nine years, including one by the Center for Naval Research and the Office of Technology Assessment, had come to similar conclusions. Interdiction efforts, using current armed forces resources, would have almost no effect on cocaine importation into the United States, the report concluded.[223]

During the early-to-mid-1990s, the Clinton administration ordered and funded a major cocaine policy study, again by RAND. The Rand Drug Policy Research Center study concluded that $3 billion should be switched from federal and local law enforcement to treatment. The report said that treatment is the cheapest way to cut drug use, stating that drug treatment is twenty-three times more effective than the supply-side "war on drugs".[224]

In mid-1995, the US government tried to reduce the supply of methamphetamine precursors to disrupt the market of this drug. According to a 2009 study, this effort was successful, but its effects were largely temporary.[225]

During alcohol prohibition, the period from 1920 to 1933, alcohol use initially fell but began to increase as early as 1922. It has been extrapolated that even if prohibition had not been repealed in 1933, alcohol consumption would have quickly surpassed pre-prohibition levels.[226] One argument against the War on Drugs is that it uses similar measures as Prohibition and is no more effective.

In the six years from 2000 to 2006, the U.S. spent $4.7 billion on Plan Colombia, an effort to eradicate coca production in Colombia. The main result of this effort was to shift coca production into more remote areas and force other forms of adaptation. The overall acreage cultivated for coca in Colombia at the end of the six years was found to be the same, after the U.S. Drug Czar's office announced a change in measuring methodology in 2005 and included new areas in its surveys.[227] Cultivation in the neighboring countries of Peru and Bolivia increased, some would describe this effect like squeezing a balloon.[228]

Richard Davenport-Hines, in his book The Pursuit of Oblivion,[229] criticized the efficacy of the War on Drugs by pointing out that

10–15% of illicit heroin and 30% of illicit cocaine is intercepted. Drug traffickers have gross profit margins of up to 300%. At least 75% of illicit drug shipments would have to be intercepted before the traffickers' profits were hurt.

Alberto Fujimori, president of Peru from 1990 to 2000, described U.S. foreign drug policy as "failed" on grounds that

for 10 years, there has been a considerable sum invested by the Peruvian government and another sum on the part of the American government, and this has not led to a reduction in the supply of coca leaf offered for sale. Rather, in the 10 years from 1980 to 1990, it grew 10-fold.[230]

At least 500 economists, including Nobel Laureates Milton Friedman,[231] George Akerlof and Vernon L. Smith, have noted that reducing the supply of marijuana without reducing the demand causes the price, and hence the profits of marijuana sellers, to go up, according to the laws of supply and demand.[232] The increased profits encourage the producers to produce more drugs despite the risks, providing a theoretical explanation for why attacks on drug supply have failed to have any lasting effect. The aforementioned economists published an open letter to President George W. Bush stating "We urge...the country to commence an open and honest debate about marijuana prohibition... At a minimum, this debate will force advocates of current policy to show that prohibition has benefits sufficient to justify the cost to taxpayers, foregone tax revenues and numerous ancillary consequences that result from marijuana prohibition."

The declaration from the World Forum Against Drugs, 2008 state that a balanced policy of drug abuse prevention, education, treatment, law enforcement, research, and supply reduction provides the most effective platform to reduce drug abuse and its associated harms and call on governments to consider demand reduction as one of their first priorities in the fight against drug abuse.[234]

Despite over $7 billion spent annually towards arresting[235] and prosecuting nearly 800,000 people across the country for marijuana offenses in 2005 (FBI Uniform Crime Reports), the federally funded Monitoring the Future Survey reports about 85% of high school seniors find marijuana "easy to obtain". That figure has remained virtually unchanged since 1975, never dropping below 82.7% in three decades of national surveys.[236] The Drug Enforcement Administration states that the number of users of marijuana in the U.S. declined between 2000 and 2005 even with many states passing new medical marijuana laws making access easier,[237] though usage rates remain higher than they were in the 1990s according to the National Survey on Drug Use and Health.[238]

ONDCP stated in April 2011 that there has been a 46 percent drop in cocaine use among young adults over the past five years, and a 65 percent drop in the rate of people testing positive for cocaine in the workplace since 2006.[239] At the same time, a 2007 study found that up to 35% of college undergraduates used stimulants not prescribed to them.[240]

A 2013 study found that prices of heroin, cocaine and cannabis had decreased from 1990 to 2007, but the purity of these drugs had increased during the same time.[241][242]

According to data collected by the Federal Bureau of Prisons 45.3% of all criminal charges were drug related and 25.5% of sentences for all charges last 5–10 years. Furthermore, non-whites make up 41.4% of the federal prison system's population and over half are under the age of 40.[243] The Bureau of Justice Statistics contends that over 80% of all drug related charges are for possession rather than the sale or manufacture of drugs.[244] In 2015 The U.S. government spent over to $25 billion on supply reduction, while allocating only $11 billion for demand reduction. Supply reduction includes: interdiction, eradication, and law enforcement; demand reduction includes: education, prevention, and treatment. The War on Drugs is often called a policy failure.[245][246][247][248][249][250]

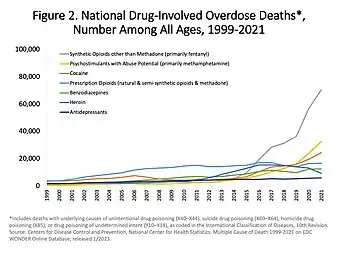

Critics of the War on Drugs have noted that it has done little to reduce the amount of deaths caused by drug use. For example, according to the CDC, drug abuse deaths in 2021 have reached an all-time high of 108,000 deaths,[251] a 15 percent increase from 2020 (93,000)[252] which, at the time, was the highest number of deaths and a 30% increase from 2019. This is despite the fact that the Obama, Trump, and Biden Administrations and prior administrations have perpetuated strict drug scheduling and mandatory minimum sentences from drug users that critics say have very little effect on reducing drug use and deaths.[251]

In 2023, the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights denounced the failure of punitive drug policies and the global War on Drugs, and called for a new approach based on health and human rights, including through the legal regulation of drugs.[253][254]

Alternatives

A prevalent critical view holds that the war on drugs has been costly and ineffective largely because US federal and state governments have chosen the wrong methods, focusing on interdiction and punishment rather than regulation and treatment. The US leads the world in both recreational drug usage and incarceration rates; 70% of men arrested in metropolitan areas test positive for an illicit substance,[255] and 54% of all men incarcerated will be repeat offenders.[256] Aggressive, heavy-handed enforcement funnels individuals through courts and prisons; instead of treating the cause of the addiction. Making drugs illegal rather than regulating them also creates a highly profitable black market. Jefferson Fish has edited scholarly collections of articles offering a wide variety of public health-based and rights-based alternative drug policies.[257][258][259]

In a survey taken by Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), it was found that substance abusers that remain in treatment longer are less likely to resume their former drug habits. Of the people that were studied, 66 percent were cocaine users. After experiencing long-term in-patient treatment, only 22 percent returned to the use of cocaine. Treatment had reduced the number of cocaine abusers by two-thirds.[260]

In the year 2000, the United States drug-control budget reached 18.4 billion dollars,[260] nearly half of which was spent financing law enforcement while only one sixth was spent on treatment. In the year 2003, 53 percent of the requested drug control budget was for enforcement, 29 percent for treatment, and 18 percent for prevention.[261] The state of New York, in particular, designated 17 percent of its budget towards substance-abuse-related spending. Of that, a mere one percent was put towards prevention, treatment, and research.

As an alternative to imprisonment, drug courts in the US identify substance-abusing offenders and place them under strict court monitoring and community supervision, as well as provide them with long-term treatment services.[262] According to a report issued by the National Drug Court Institute, drug courts have a wide array of benefits, with only 16.4 percent of the nation's drug court graduates rearrested and charged with a felony within one year of completing the program (versus the 44.1% of released prisoners who end up back in prison within one year). Additionally, enrolling an addict in a drug court program costs much less than incarcerating one in prison.[263] According to the Bureau of Prisons, the fee to cover the average cost of incarceration for Federal inmates in 2006 was $24,440.[264] The annual cost of receiving treatment in a drug court program ranges from $900 to $3,500. Drug courts in New York State alone saved $2.54 million in incarceration costs.[263]

Considering outright legalization of recreational drugs, New York Times columnist Eduardo Porter noted: "Jeffrey Miron, an economist at Harvard who studies drug policy closely, has suggested that legalizing all illicit drugs would produce net benefits to the United States of some $65 billion a year, mostly by cutting public spending on enforcement as well as through reduced crime and corruption. A study by analysts at the RAND Corporation, a California research organization, suggested that if marijuana were legalized in California and the drug spilled from there to other states, Mexican drug cartels would lose about a fifth of their annual income of some $6.5 billion from illegal exports to the United States."[265]

See also

- Baker, a series of counter-narcotics training exercises conducted by the United States Army and several Asian countries

- Cartoon All-Stars to the Rescue

- Chasing the Scream

- Civil forfeiture in the United States

- Class war

- Cognitive liberty

- Crack epidemic

- Drugs in the United States

- Harm reduction

- Latin American drug legalization

- Law Enforcement Action Partnership

- November Coalition

- Philippine Drug War

- Prison-industrial complex

- Race war

- Recreational use of drugs

- Smoke and Mirrors: The War on Drugs and the Politics of Failure

- Victimless crime

- War on Gangs

Covert activities and foreign policy

- Allegations of CIA drug trafficking

- Golden Crescent

- Golden Triangle

- Harry J. Anslinger

- Military Cooperation with Civilian Law Enforcement Agencies Act

- CIA transnational anti-crime and anti-drug activities

- Plan Colombia

- UMOPAR

- Air Bridge Denial Program

Government agencies and laws

Notes

References

- 1 2 War on Drugs. The Global Commission on Drug Policy. 2011. p. 24. Archived from the original on January 9, 2016. Retrieved September 18, 2017.

- ↑ Baum, Writer Dan. "Legalize All Drugs? The 'Risks Are Tremendous' Without Defining The Problem". NPR.org. Archived from the original on January 15, 2018. Retrieved April 3, 2018.

- ↑ "(And) Richard Nixon was the one who coined the phrase, 'war on drugs.'"

- 1 2 Cockburn and St. Clair, 1998: Chapter 14

- 1 2 Bullington, Bruce; Block, Alan A. (March 1990). "A Trojan horse: Anti-communism and the war on drugs". Crime, Law and Social Change. 14 (1): 39–55. doi:10.1007/BF00728225. ISSN 1573-0751. S2CID 144145710.

- 1 2 Mann, Brian (June 17, 2021). "After 50 Years Of The War On Drugs, 'What Good Is It Doing For Us?'". NPR. Retrieved December 8, 2023.

- ↑ "Richard Nixon: Special Message to the Congress on Drug Abuse Prevention and Control". Archived from the original on December 12, 2013. Retrieved December 8, 2013.

- ↑ "Nixon Calls War on Drugs". Palm Beach Post. June 18, 1971. Retrieved December 8, 2023.

- ↑ Dufton, Emily (March 26, 2012). "The War on Drugs: How President Nixon Tied Addiction to Crime". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on November 5, 2012. Retrieved October 13, 2012.

- ↑ "Drug War Statistics". Drug Policy Alliance. Archived from the original on July 5, 2017. Retrieved February 25, 2014.

- ↑ Mann, Brian (June 17, 2021). "After 50 Years Of The War On Drugs, 'What Good Is It Doing For Us?'". NPR.

The campaign – which by some estimates cost more than $1 trillion – also exacerbated racial divisions and infringed on civil liberties in ways that transformed American society.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Trickey, Erick (January 4, 2018). "Inside the Story of America's 19th-Century Opiate Addiction". The Smithsonian. Archived from the original on January 5, 2019. Retrieved December 25, 2023.

- 1 2 3 Das, G (April 1993). "Cocaine abuse in North America: a milestone in history". Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 33 (4): 296–310. doi:10.1002/j.1552-4604.1993.tb04661.x. PMID 8473543 – via PubMed.

- 1 2 3 "Cocaine". History.com. August 21, 2018. Retrieved December 15, 2023.

- ↑ "Marijuana Timeline". PBS Frontline. Retrieved December 15, 2023.

- 1 2 "Heroin, Morphine and Opiates". history.com. June 10, 2019. Retrieved March 28, 2021.

- ↑ Courtwright DT (2009). Forces of habit drugs and the making of the modern world. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press. pp. 36–37. ISBN 978-0674029903. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017.

- 1 2 McKendry, Joe (March 2019). "Sears Once Sold Heroin". The Atlantic. Retrieved December 25, 2023.

- ↑ The Editorial Board (April 21, 2018). "Opinion – An Opioid Crisis Foretold". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 22, 2019. Retrieved January 21, 2019.

- ↑ "The United States War on Drugs". web.stanford.edu. Archived from the original on January 6, 2019. Retrieved January 21, 2019.

- ↑ The Editorial Board (April 21, 2018). "Opinion – An Opioid Crisis Foretold". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 22, 2019. Retrieved January 21, 2019.

- ↑ "The United States War on Drugs". web.stanford.edu. Archived from the original on January 6, 2019. Retrieved January 21, 2019.

- 1 2 Cockburn, Alexander; Jeffrey St. Clair (1998). Whiteout: The CIA, Drugs and the Press. Verso. ISBN 1-85984-139-2.

- 1 2 Johnston, Ann Dowsett (November 15, 2013). "'Drink' and 'Her Best-Kept Secret'". The New York Times. Retrieved August 9, 2023.

In 1897, the Sears, Roebuck catalog offered a kit with a syringe, two needles, two vials of heroin and a handy carrying case for $1.50.

- 1 2 "Sears Once Sold Heroin". The Atlantic. January 30, 2019. Retrieved August 9, 2023.

For $1.50, Americans around the turn of the century could place an order through a Sears, Roebuck catalog and receive a syringe, two needles, and two vials of Bayer Heroin, all in a handsome carrying case.

- 1 2 "War on Drugs". History.com. May 31, 2017. Retrieved December 8, 2023.

- ↑ "Opium prohibition law in library of congress" (PDF). Library of Congress. Retrieved May 14, 2019.

- ↑ "Opium and Narcotic Laws". Office of Justice Programs. Retrieved December 8, 2023.

- ↑ "Opium Throughout History". PBS Frontline. Archived from the original on September 23, 2006. Retrieved October 8, 2010.

- ↑ "Harrison Narcotics Tax Act, 1914". Drug Reform Coordination Network. Retrieved November 18, 2013.

- ↑ "Records of the Drug Enforcement Administration DEA". Archives.gov. Archived from the original on May 21, 2011. Retrieved March 27, 2011.

- ↑ Filan, Kenaz (February 23, 2011). The Power of the Poppy: Harnessing Nature's Most Dangerous Plant Ally. Rochester, Vt.: Park Street Press. p. 64. ISBN 978-1-59477-399-0.

- ↑ Krebs, Albin (November 18, 1975). Sulzberger Sr., Arthur Ochs (ed.). "Harry J. Anslinger Dies at 83; Hard‐Hitting Foe of Narcotics". The New York Times. Vol. CXXIV, no. 236. p. 40. Retrieved September 10, 2021.

Harry J. Anslinger, an implacable, hard-hitting foe of drug pushers and users during the 32 years he was the Treasury Department's Commissioner of Narcotics, died Friday in Hollidaysburg, Pa. His age was 83.

- ↑ Smith, Benjamin T. (June 2021). "Why we should remember Richard Nixon's war on drugs". History Extra. Retrieved January 6, 2024.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ↑ Chasin, Alexandra (September 30, 2016). Assassin of Youth: A Kaleidoscopic History of Harry J. Anslinger's War on Drugs. Chicago, Illinois, United States of America: University of Chicago Press. doi:10.7208/chicago/9780226277028.001.0001. ISBN 9780226276977. LCCN 2016011027. Retrieved September 10, 2021 – via Google Books.

- ↑ "Roosvelt Asks Narcotics War Aid, 1935". Druglibrary.net. Archived from the original on July 23, 2011. Retrieved March 27, 2011.

- ↑ "Letter to the World Narcotic Defense Association. March 21, 1935". Presidency.ucsb.edu. Archived from the original on February 3, 2012. Retrieved March 27, 2011.

- ↑ For repeal, see section 1101(b)(3), Comprehensive Drug Abuse Prevention and Control Act of 1970, Pub. L. No. 91-513, 84 Stat. 1236, 1292 (Oct. 27, 1970) (repealing the Marihuana Tax Act which had been codified in Subchapter A of Chapter 39 of the Internal Revenue Code of 1954).

- ↑ Glick, Daniel (December 6, 2016). "80 Years Ago This Week, Marijuana Prohibition Began With These Arrests". Leafly.

- ↑ "Statement of Dr. William C. Woodward, Legislative Counsel, American Medical Association". Retrieved March 25, 2006.

- ↑ Committee on Finance, U.S. Senate, 75c 2s. HR6906. Library of Congress transcript. July 12, 1937

- ↑ French, Laurence; Manzanárez, Magdaleno (2004). NAFTA & neocolonialism: comparative criminal, human & social justice. University Press of America. p. 129. ISBN 978-0-7618-2890-7. Archived from the original on December 28, 2019. Retrieved May 7, 2020.

- ↑ Earlywine, 2005: p. 24 Archived January 10, 2016, at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Peet, 2004: p. 55

- ↑ Evans, Sterling (2007). Bound in twine: the history and ecology of the henequen-wheat complex for Mexico and the American and Canadian Plains, 1880–1950. Texas A&M University Press. p. 27. ISBN 978-1-58544-596-7. Archived from the original on April 24, 2016. Retrieved March 6, 2016.

- ↑ Evans, Sterling, ed. (2006). The borderlands of the American and Canadian Wests: essays on regional history of the forty-ninth parallel. University of Nebraska Press. p. 199. ISBN 978-0-8032-1826-0.

- ↑ Gerber, Rudolph Joseph (2004). Legalizing marijuana: drug policy reform and prohibition politics. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 7. ISBN 978-0-275-97448-0. Archived from the original on January 8, 2016. Retrieved March 6, 2016.

- ↑ Earleywine, Mitchell (2005). Understanding marijuana: a new look at the scientific evidence. Oxford University Press. p. 231. ISBN 978-0-19-518295-8. Archived from the original on January 8, 2016. Retrieved March 6, 2016.

- ↑ Robinson, Matthew B. & Scherlen, Renee G. (2007). Lies, damned lies, and drug war statistics: a critical analysis of claims made by the office of National Drug Control Policy. SUNY Press. p. 12. ISBN 978-0-7914-6975-0. Archived from the original on January 8, 2016. Retrieved March 6, 2016.

- ↑ Rowe, Thomas C. (2006). Federal narcotics laws and the war on drugs: money down a rat hole. Psychology Press. p. 26. ISBN 978-0789028082. Archived from the original on January 8, 2016. Retrieved March 6, 2016.

- ↑ Sullivan, Larry E.; et al., eds. (2005). Encyclopedia of Law Enforcement: Federal. Sage. p. 747. ISBN 978-0761926498. Archived from the original on January 8, 2016. Retrieved March 6, 2016.

- ↑ Lusane, Clarence (1991). Pipe dream blues: racism and the war on drugs. South End Press. pp. 37–38. ISBN 978-0896084100.

- ↑ "Was there a conspiracy to outlaw hemp because it was a threat to theDuPonts and other industrial interests?". Archived from the original on April 2, 2015. Retrieved March 17, 2015.

- ↑ LH, Dewey (1943). "Fiber production in the western hemisphere". United States Printing Office, Washington. p. 67. Archived from the original on March 13, 2016. Retrieved February 25, 2015.

- ↑ Fortenbery, T. Randall; Bennett, Michael (July 2001). "Is Industrial Hemp Worth Further Study in the US? A Survey of the Literature" (PDF). Department of Agricultural and Applied Economics, University of Wisconsin-Madison. p. 25. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved June 25, 2014.

- ↑ Lassiter, Matthew D. (December 7, 2023). "America's War on Drugs Has Always Been Bipartisan—and Unwinnable". Time. Retrieved December 21, 2023.