Washington Harrison Donaldson | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | October 10, 1840[1] |

| Died | July 15, 1875 (aged 34) |

| Years active | 1871 to 1875 |

| Known for | Balloonist |

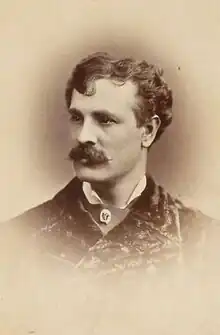

Washington Harrison Donaldson (10 October 1840 in Philadelphia – 15 July 1875 in Lake Michigan) was a 19th-century balloonist who worked in the United States. He was known as much for his failures as his successes.

Biography

His early life was spent upon the stage as a gymnast, ventriloquist, and magician. He was a graceful tight rope performer. In 1862 he walked across the Schuylkill River on a rope 1,200 feet (370 m) long, returning to the middle and finishing by jumping into the river from a height of 90 feet (27 m). He also walked across the Genesee River at Rochester, New York on a rope 1,800 feet (550 m) long, recrossing it with a man in a wheelbarrow trundled in front of him. From 1857 until 1871 he travelled through the United States, appearing not fewer than 1,300 times in his various specialties.[2]

Bartering instruction in magic and all the paraphernalia of his exhibitions, Donaldson found himself the owner of a balloon. Without the slightest previous knowledge of balloon management, he made arrangements for an ascension, taking his first lesson in a failure, which happened for want of lighter gas or a larger balloon, the latter being too small to carry him except with pure hydrogen. The balloon was enlarged and tried again with coal gas, as in his previous attempt. This time, 30 August 1871, it succeeded in getting off after Donaldson had thrown away every available thing, even his coat, boots, and hat. This ascent was made from Reading, Pennsylvania, and the descent 18 miles (29 km) distant. He made another ascent from Reading in September upon a trapeze bar.[2]

On 18 January 1872, he ascended from Norfolk, Virginia, and his balloon accidentally burst when a mile from the ground. He said of it:

“The balloon did not collapse, but closed up at the sides, and, swaying from side to side, descended with frightful velocity. I clung with all my strength to the hoop. I could not tell how badly I was frightened, but felt as though all my hair had been torn out. I scarcely had time to realize that I was alive, when, with a crash, I was projected with the velocity of a catapult into a burr chestnut tree. The netting and rigging, catching in the tree, checked my velocity, but I had my grasp jerked loose, and was precipitated through the limbs and landed flat upon my back, with my tights nearly torn off, and my legs, arms, and body lacerated and bleeding.”[2]

Shortly after this, he ascended again from Norfolk. This time, in his haste to avoid being carried out to sea, his balloon was wrecked among the trees, although he himself escaped injury.[2]

He then undertook the construction of a balloon which he called the “Magenta.” It was made of fine jaconet, held about 10,000 cubic feet (280 m3) of gas, and weighed about 100 pounds. He made several ascensions with this balloon, two of which were from Chicago. On the first occasion he was carried out over Lake Michigan and dragged more than a mile through the water, bringing up against a stone pier finally with such violence as to render him insensible. On 17 May 1873, he ascended from Reading, Pa., in a balloon made of manilla paper enclosed with a light network, the whole weighing but 48 pounds, although it contained 14,000 cubic feet (400 m3) of gas. He travelled ten miles (16 km) before landing.[2]

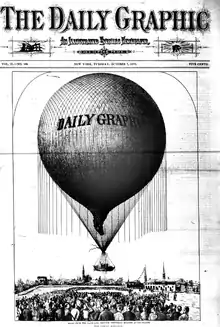

Donaldson was a convert to John Wise's theory of a constant current blowing from west to east at a height of three miles (4.8 km), and, as the veteran aeronaut had said a balloon could cross the ocean in this current, Donaldson was ready to take the venture, and so announced his intention of making the attempt. Wise offered to join him, and they set out together to raise the necessary funds, they went to New York City and opened a subscription, but while this was in progress the proprietors of the Daily Graphic offered to furnish the funds required for the construction of a very large balloon and outfit, together with the gas required. This proposition was accepted.[2]

The construction of an immense balloon of cotton twill was carried to completion. But before the inflation some differences arose between the aeronauts regarding the reliability of the balloon. Donaldson's inexperience placed him in a secondary position throughout the entire transaction, but when the time for action came he found himself the principal, Wise having withdrawn. The dimensions of the balloon were enormous enough to be beyond the capabilities of Donaldson's management at that time. Three unsuccessful attempts were made at inflation, the balloon bursting each time, when finally the aeronaut Samuel Archer King was sent for, and the work was accomplished.[2]

The ascension made from the Capitoline baseball grounds in Brooklyn, New York, on 7 October 1873. Donaldson had two companions, named Ford and Lunt. A handsome lifeboat, filled with provisions and loaded with great quantities of sand, was hung beneath the balloon. It served both as car and as a means of escape in case of falling into the ocean. But they never reached the sea. Fortunately, they kept inland sufficiently to clear the water till it became manifest that the aeronaut was as incapable of managing the mammoth globe in the air as he had been on the ground. Scarcely one hundred miles had been run when control was completely lost, and the voyagers found themselves dashing about among trees and fences, and coming close to the ground. Donaldson gave the word to jump, and Ford jumped with Donaldson, but Lunt was too late. A thousand-pound drag rope was trailing, which prevented the balloon from rising to any considerable height after the two men had left the car, and Lunt, panic stricken at finding himself alone with the monster, threw himself bodily into the first tree the boat came in contact with near Canaan, Connecticut, and fell through to the ground without being able to stop himself. He died six months later.[2]

P. T. Barnum offered Donaldson an engagement, first at Gilmore's Garden and then with his hippodrome, which was accepted. On 24 July 1874, Donaldson ascended from Gilmore's Garden in a balloon containing 54,000 cubic feet (1,500 m3) of gas, with five passengers; these he continued to land one after another as the balloon became weakened; but by resorting to the use of the drag rope he was able to keep afloat for thirteen hours, landing finally at Greenport, near Hudson, 130 miles (210 km) from New York. Four days afterward he again ascended from Gilmore's Garden. Three hours after starting, two passengers were landed, and the voyage continued into the night. At 2 A. M. a landing was effected at Wallingford, Vermont, the journey being resumed at 8 A. M., and at noon the voyage terminated at Thetford, Vermont.[2]

On 19 October of the same year Donaldson took up a wedding party from Cincinnati, the ceremony being performed in mid-air. On 23 June 1875, he ascended from Toronto, taking three newspaper reporters with him. They were carried out over Lake Ontario, and finally descended into the water, through which they were dragged for several miles before they were rescued by a boat's crew sent out from a passing schooner. Donaldson, during his tour with the hippodrome, made numerous ascensions. From Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, he ascended with five women and one man, making a pleasant and safe voyage. On 17 June 1875, he ascended from Buffalo, accompanied by two reporters and his friend Samuel King. They expected to have an experience over Lake Erie, but after a sail of twenty miles (32 km) or more over the water they reached the Canada shore, landing finally near Port Colborne.[2]

On 14 July 1875, Donaldson ascended from the lake front in Chicago, carrying several persons with him. The air being very still, the balloon, although it drifted lakeward, did not get more than three miles (4.8 km) from the shore, and was towed back to the starting-place with most of the gas remaining in it, and held for the ascension of the following day. One of the hippodrome managers, looking at the balloon, inquired of Donaldson: “What's the use of this? Why didn't you go somewhere?” “Wait till to-morrow,” he replied, “and I'll go far enough for you.”[2]

On the following day the wind was blowing up the lake at the rate of ten to fifteen miles (24 km) an hour. An additional amount of gas was supplied to make up for what had been lost; but, in consequence of the deterioration of what had been in the balloon since the previous day, the buoyancy was not as great as usual. Knowing that he would have a long voyage up the lake, he determined to take but one companion with him, Newton S. Grimwood, of the Chicago Evening Journal, drawing the prize, as it was then considered. At 5 P. M. the voyage began. The balloon gradually rose to the height of a mile or more, floating off up the lake, and in about an hour and a half disappeared.[2]

At seven o'clock the crew of the “Little Guide,” a small craft, saw the balloon about thirty miles from shore, trailing the car through the water, and tried to reach it; but before this could be done, the balloon, as if suddenly relieved of some weight, shot up into the air again and off into the distance. Night came on, and, with the cooling gas and natural loss of buoyancy, the luckless aeronauts doubtless came down upon the lake again. But they might have escaped with their lives had it not been for a violent storm which came up about eleven o'clock. The body of Grimwood was washed ashore on the farther side of the lake, and was found on 16 August. Donaldson never was found, nor any part of the balloon.[2]

In popular culture

In The Annotated Wizard of Oz, Michael Patrick Hearn suggests that Donaldson may have been an inspiration for L. Frank Baum in creating the title character of The Wonderful Wizard of Oz. Like Donaldson, the Wizard of Oz was a balloonist, ventriloquist and stage magician who worked for a circus, but disappeared, balloon and all, during an ascent, and was never found.[3]

Notes

References

- Early Balloon Flight in the United States at centennialofflight.net

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Wilson, J. G.; Fiske, J., eds. (1900). . Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography. New York: D. Appleton.