Wends (Old English: Winedas [ˈwi.ne.dɑs]; Old Norse: Vindar; German: Wenden [ˈvɛn.dn̩], Winden [ˈvɪn.dn̩]; Danish: Vendere; Swedish: Vender; Polish: Wendowie, Czech: Wendové) is a historical name for Slavs who inhabited present-day northeast Germany. It refers not to a homogeneous people, but to various peoples, tribes or groups depending on where and when it was used. In the modern day, communities identifying as Wendish exist in Slovenia, Austria, Lusatia, the United States (such as the Texas Wends),[1] and Australia.[2]

In German-speaking Europe during the Middle Ages, the term "Wends" was interpreted as synonymous with "Slavs" and sporadically used in literature to refer to West Slavs and South Slavs living within the Holy Roman Empire. The name has possibly survived in Finnic languages (Finnish: Venäjä [ˈʋe̞.næ.jæ], Estonian: Vene [ˈve.ne], Karelian: Veneä), denoting modern Russia.[3][4]

Term

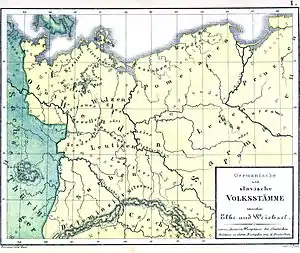

According to one theory, Germanic peoples first applied this name to the ancient Veneti. For the medieval Scandinavians, the term Wends (Vender) meant Slavs living near the southern shore of the Baltic Sea (Vendland), and the term was therefore used to refer to Polabian Slavs like the Obotrites, Rugian Slavs, Veleti/Lutici, and Pomeranian tribes.

For people living in the medieval Northern Holy Roman Empire and its precursors, especially for the Saxons, a Wend (Wende) was a Slav living in the area west of the River Oder, an area later entitled Germania Slavica, settled by the Polabian Slav tribes (mentioned above) in the north and by others, such as the Sorbs and the Milceni, further south (see Sorbian March).

The Germans in the south used the term Winde instead of Wende and applied it, just as the Germans in the north, to Slavs they had contact with; e.g., the Polabians from Bavaria Slavica or the Slovenes (the names Windic March, Windisch Feistritz, Windischgraz, or Windisch Bleiberg near Ferlach still bear testimony to this historical denomination). The same term was sometimes applied to the neighboring region of Slavonia, which appears as Windischland in some documents prior to the 18th century.

Following the 8th century, the Frankish kings and their successors organised nearly all Wendish land into marches. This process later turned into the series of Crusades. By the 12th century, all Wendish lands had become part of the Holy Roman Empire. In the course of the Ostsiedlung, which reached its peak in the 12th to 14th centuries, this land was settled by Germans and reorganised.

Due to the process of assimilation following German settlement, many Slavs west of the Oder adopted the German culture and language. Only some rural communities which did not have a strong admixture with Germans and continued to use West Slavic languages were still termed Wends. With the gradual decline of the use of these local Slavic tongues, the term Wends slowly disappeared, too.

Some sources claim that in the 13th century there were actual historic people called Wends or Vends living as far as northern Latvia (east of the Baltic Sea) around the city of Wenden. Henry of Livonia (Henricus de Lettis) in his 13th-century Latin chronicle described a tribe called the Vindi.

Today, only one group of Wends still exists: the Lusatian Sorbs in present-day Eastern Germany, with international diaspora.[5]

Roman-era Veneti

The term "Wends" derived from the Roman-era people called in Latin: Venetī, Venethī [ˈwe.ne.t̪ʰiː] or Venedī [ˈwe.ne.d̪iː]; in Greek: Οὐενέδαι, translit. Ouenédai [u.eˈne.ðe]. This people is mentioned by Pliny the Elder and Ptolemy as inhabiting the Baltic coast.

History

Rise (700–1000)

In the 1st millennium AD, during the Slavic migrations which split the Slavs into Southern, Eastern and Western groups, some West Slavs moved into the areas between the Rivers Elbe and Oder - moving from east to west and from south to north. There they assimilated the remaining Germanic population that had not left the area in the Migration period.[6] Their German neighbours adapted the term they had been using for peoples east of the River Elbe before to the Slavs, calling them Wends as they called the Venedi before and probably the Vandals as well. In his late sixth century work History of Armenia, Movses Khorenatsi mentions their raids into the lands named Vanand after them.[7]

While the Wends were arriving as large homogeneous groups, they soon divided into a variety of small tribes, with large strips of woodland separating one tribal settlement area from another. Their tribal names were derived from local place names, sometimes adopting the Germanic tradition (e.g. Heveller from Havel, Rujanes from Rugians). Settlements were secured by round burghs made of wood and clay, where either people could retreat in case of a raid from the neighbouring tribe or used as military strongholds or outposts.

Some tribes unified into larger, duchy-like units. For example, the Obotrites evolved from the unification of the Holstein and Western Mecklenburg tribes led by mighty dukes known for their raids into German Saxony. The Lutici were an alliance of tribes living between Obotrites and Pomeranians. They did not unify under a duke, but remained independent. Their leaders met in the temple of Rethra.

In 983, many Wend tribes participated in a great uprising against the Holy Roman Empire, which had previously established Christian missions, German colonies and German administrative institutions (Marken such as Nordmark and Billungermark) in pagan Wendish territories. The uprising was successful and the Wends delayed Germanisation for about two centuries.

Wends and Danes had early and continuous contact including settlement, first and mainly through the closest South Danish islands of Møn, Lolland and Falster, all having place-names of Wendish origin. There were also trading and settlement outposts by Danish towns as important as Roskilde, when it was the capital: 'Vindeboder' (Wends' booths) is the name of a city neighbourhood there. Danes and Wends also fought wars due to piracy and crusading.[8]

Decline (1000–1200)

After their successes in 983 the Wends came under increasing pressure from Germans, Danes and Poles. The Poles invaded Pomerania several times. The Danes often raided the Baltic shores (and, in turn, the Wends often raided the raiders). The Holy Roman Empire and its margraves tried to restore their marches.

In 1068/69 a German expedition took and destroyed Rethra, one of the major pagan Wend temples. The Wendish religious centre shifted to Arkona thereafter. In 1124 and 1128, the Pomeranians and some Lutici were baptised. In 1147, the Wend crusade took place in what is today north-eastern Germany.

This did not, however, affect the Wendish people in today's Saxony, where a relatively stable co-existence of German and Slavic inhabitants as well as close dynastic and diplomatic cooperation of Wendish and German nobility had been achieved. (See: Wiprecht of Groitzsch).

In 1168, during the Northern Crusades, Denmark mounted a crusade led by Bishop Absalon and King Valdemar the Great against the Wends of Rugia in order to convert them to Christianity. The crusaders captured and destroyed Arkona, the Wendish temple-fortress, and tore down the statue of the Wendish god Svantevit. With the capitulation of the Rugian Wends, the last independent pagan Wends were defeated by the surrounding Christian feudal powers.

From the 12th to the 14th centuries, Germanic settlers moved into the Wendish lands in large numbers, transforming the area's culture from a Slavic to a Germanic one. Local dukes and monasteries invited settlers to repopulate farmlands devastated in the wars, as well as to cultivate new farmlands from the expansive woodlands and heavy soils, with the use of iron-based agricultural tools that had developed in Western Europe. Concurrently, a large number of new towns were created under German town law with the introduction of legally enforced markets, contracts and property rights. These developments over two centuries were collectively known as the Ostsiedlung (German eastward expansion). A minority of Germanic settlers moved beyond the Wendish territory into Hungary, Bohemia and Poland, where they were generally welcomed for their skills in farming and craftsmanship.

The Polabian language was spoken in the central area of Lower Saxony and in Brandenburg until around the 17th or 18th century.[9][10] The German population assimilated most of the Wends, meaning that they disappeared as an ethnic minority - except for the Sorbs. Yet many place names and some family names in eastern Germany still show Wendish origins today. Also, the Dukes of Mecklenburg, of Rügen and of Pomerania had Wendish ancestors.

Between 1540 and 1973, the kings of Sweden were officially called kings of the Swedes, the Goths and the Wends (in Latin translation: kings of Suiones, Goths and Vandals) (Swedish: Svears, Götes och Wendes Konung). After the Danish monarch Queen Margrethe II chose not to use these titles in 1972 the current Swedish monarch, Carl XVI Gustaf also chose only to use the title King of Sweden" (Sveriges Konung), thereby changing an age-old tradition.

From the Middle Ages the kings of Denmark and of Denmark–Norway used the titles King of the Wends (from 1362) and Goths (from the 12th century). The use of both titles was discontinued in 1973.[11]

Legacy

The Wendish people co-existed with the German settlers for centuries and became gradually assimilated into the German-speaking culture.

The Golden Bull of 1356 (one of the constitutional foundations of the German-Roman Empire) explicitly recognised in its Art. 31 that the German-Roman Empire was a multi-national entity with "diverse nations distinct in customs, manner of life, and in language".[12] For that it stipulated "the sons, or heirs and successors of the illustrious prince electors, ... since they are expected in all likelihood to have naturally acquired the German language, ... shall be instructed in the grammar of the Italian and Slavic (i.e. Wendish) tongues, beginning with the seventh Year of their age."[13]

Many geographical names in Central Germany and northern Germany can be traced back to a Slavic origin. Typical Slavic endings include -itz, -itzsch and -ow. They can be found in city names such as Delitzsch and Rochlitz. Even names of major cities like Leipzig and Berlin are most likely of Wendish origin.

Today, the only remaining minority people of Wendish origin, the Sorbs, maintain their traditional language and culture and enjoy cultural self-determination exercised through the Domowina. The third minister president of Saxony Stanislaw Tillich (2008–2017) is of Sorbian origin, being the first head of a German federal state with an ethnic minority background.

The Texas Wends

In 1854, the Wends of Texas departed Lusatia on the Ben Nevis[14] seeking greater liberty, in order to settle an area of central Texas, primarily Serbin. The Wends succeeded, expanding into Warda, Giddings, Austin, Houston, Fedor, Swiss Alp, Port Arthur, Mannheim, Copperas Cove, Vernon, Walburg, The Grove, Bishop, and the Rio Grande Valley.

A strong emphasis on tradition, principles, and education is evident today in families descendant from the Wendish pioneers. Today, thousands of Texans and other Americans (many unaware of their background), can lay claim to the heritage of the Wends.[15]

Other uses

Historically, the term "Wends" has also occurred in the following contexts:

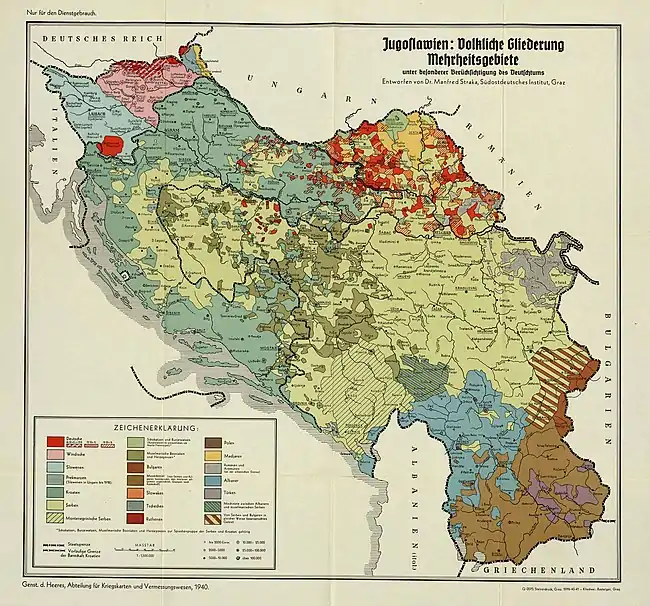

- Until the mid-19th-century German-speakers most commonly used the name Wenden to refer to Slovenes. This usage is mirrored in the name of the Windic March, a Medieval territory in present-day Lower Carniola, which merged with the Duchy of Carniola by the mid 15th century. With the diffusion of the term slowenisch for the Slovene language and Slowenen for Slovenes, the words windisch and Winde or Wende became derogatory in connotation. The same development could be seen in the case of the Hungarian Slovenes, who used to be known under the name "Vends".

- Windischentheorie was a 1927 work by Martin Wutte, a Carinthian German nationalist historian.

- It was also used to denote the Slovaks in German-language texts before c. 1400.

- The German term "Windischland" was used in the Middle Ages for the historical Kingdom of Slavonia (in Croatia).[16] The terms Veneta, Wenden, Winden etc. were used in reference to the westernmost Slavs in the 1st and 2nd century CE, as a reference to the name of the earlier tribes of Veneti.[17]

See also

References

- ↑ "Who Are the Wends?". January 2010.

- ↑ "History of Migration".

- ↑ Campbell, Lyle (2004). Historical Linguistics. MIT Press. p. 418. ISBN 0-262-53267-0.

- ↑ Bojtár, Endre (1999). Foreword to the Past. Central European University Press. p. 88. ISBN 9639116424.

- ↑ "Museum". 29 January 2015.

- ↑ Brather, Sebastian (2004). "The beginnings of Slavic settlement east of the river Elbe". Antiquity, Volume 78, Issue 300. pp. 314–329

- ↑ Istorija Armenii Mojseja Horenskogo, II izd. Per. N. O. Emina, M., 1893, s.55-56.

- ↑ "Venderne og Danmark" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on November 16, 2012.

- ↑ Harry van der Hulst. Word Prosodic Systems in the Languages of Europe. Walter de Gruyter. 1999. p. 837.

- ↑ Britannica Online Encyclopedia. Lekhitic languages. Retrieved 2013-03-09.

- ↑ "Kungl. Maj:ts kungörelse med anledning av konung Gustaf VI Adolfs frånfälle". Lagen.nu. Archived from the original on 12 July 2014.

- ↑ Charles IV, Golden Bull of 1356 (full text English translation) translated into English, Yale

- ↑ Charles IV, Golden Bull of 1356 (full text English translation) translated into English, Yale

- ↑ "Ben Nevis, Wends and German Texans".

- ↑ "Who Are the Wends?". January 2010.

- ↑ Slavonia (in Croatian). Miroslav Krleža Lexicographical Institute. 2021. Retrieved 15 December 2021.

- ↑ Gluhak, Alemko (2003). "The name "Slavonia"". Migration and Ethnic Themes (in Croatian). Zagreb, Croatia: Institute for Migration and Ethnic Studies. 19 (1). ISSN 1848-9184.

Further reading

- Lencek, R. L. (1990). "The Terms Wende-Winde, Wendisch-Windisch in the Historiographic Tradition of the Slovene Lands". Slovene Studies. 12 (1): 93–97. doi:10.7152/ssj.v12i1.3797.

- Knox, Ellis Lee (1980). The Destruction and Conversion of the Wends: A History of Northeast Germany in the Central Middle Ages. Department of History (Master's thesis). University of Utah. Archived from the original on 12 November 2001.