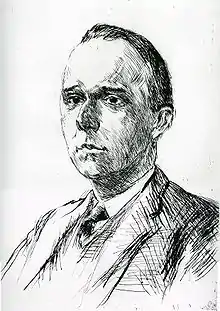

Werner Wilhelm Jaeger (30 July 1888 – 19 October 1961) was a German-American classicist.

Life

Werner Wilhelm Jaeger was born in Lobberich, Rhenish Prussia in the German Empire. He attended school in Lobberich and at the Gymnasium Thomaeum in Kempen. Jaeger studied at the University of Marburg and University of Berlin. He received a Ph.D. from the latter in 1911 for a dissertation on the Metaphysics of Aristotle. His habilitation was on Nemesios of Emesa in 1914. At only 26 years old, Jaeger was called to the professorial chair in Greek at the University of Basel in Switzerland once held by Friedrich Nietzsche. One year later, he moved to a similar position at Kiel, and in 1921 he returned to Berlin, succeeding to Ulrich von Wilamowitz-Moellendorff. Jaeger remained in Berlin until 1936.

That year, he emigrated to the United States because he was unhappy with the rise of Nazism. Jaeger expressed his veiled disapproval in 1937 with Humanistische Reden und Vorträge (Humanist Speeches and Lectures), and his book Demosthenes (1938) based on his Sather lecture from 1934. Jaeger's messages were fully understood in German university circles, with Nazi academics sharply attacking him.

In 1944, he was elected as a member to the American Philosophical Society.[1]

In the United States, Jaeger worked as a full professor at the University of Chicago from 1936 to 1939. He then moved to Harvard University to continue his edition of the Church father Gregory of Nyssa on which he had started before World War I. Jaeger would remain in Cambridge, Massachusetts, until his death.

The American classicist Robert Renehan[2] and Canadian philosophers James Doull and Robert Crouse were among his students at Harvard.

Scholarly work

Interpretation of Plato and Aristotle

Jaeger's position concerning the history of the interpretation of Plato and Aristotle has been summarized by Harold Cherniss of Johns Hopkins University. In general, the history of the interpretation of Plato and Aristotle has largely followed the outline of those who subscribe to the position that (a) Aristotle was sympathetic to the reception of Plato's early dialogues and writings, that (b) Aristotle was sympathetic to the reception of Plato's later dialogues and writings, and (c) various combinations and variations of these two positions. Cherniss' reading of Jaeger states, "Werner Jaeger, in whose eyes Plato's philosophy was the 'matter' out of which the newer and higher form of Aristotle's thought proceeded by a gradual but steady and undeviating development (Aristoteles, p. 11), pronounced the 'old controversy,' [which was] whether or not Aristotle understood Plato, to be 'absolut verständnislos.' (absolutely uncomprehending [of Aristotle]). Yet this did not prevent Dieter Leisegang[3] from reasserting that Aristotle's own pattern of thinking was incompatible with a proper understanding of Plato."[4]

Works

- Emendationum Aristotelearum specimen (1911)

- Studien zur Enstehungsgeschichte der Metaphysik des Aristoteles (1911)

- Nemesios von Emesa. Quellenforschung zum Neuplatonismus und seinen Anfaengen bei Poseidonios (1914)

- Gregorii Nysseni Opera, vol. I-X (since 1921, latest 2009)

- Aristoteles: Grundlegung einer Geschichte seiner Entwicklung (1923; English trans. by Richard Robinson (1902-1996) as Aristotle: Fundamentals of the History of His Development, 1934)

- Platons Stellung im Aufbau der griechischen Bildung (1928)

- Paideia; die Formung des griechischen Menschen, 3 vols. (German, 1933–1947; trans. by Gilbert Highet as Paideia: The Ideals of Greek Culture, 1939–1944)

- Humanistische Reden und Vorträge (1937)

- Demosthenes (Sather Classical Lecture), 1934, 1938 trans. by Edward Schouten Robinson; German edition 1939)

- Humanism and Theology, (Milwaukee: Marquette University Press, 1943)

- The Theology of the Early Greek Philosophers (Gifford Lectures) 1936, translated by Edward Schouten Robinson,1947; 1953 German edition

- Two rediscovered works of ancient Christian literature: Gregory of Nyssa and Macarius,1954

- Aristotelis Metaphysica, 1957

- Scripta Minora, 2 vol., 1960

- Early Christianity and Greek Paideia, 1961

- Gregor von Nyssas Lehre vom Heiligen Geist, 1966

References

- ↑ "APS Member History". search.amphilsoc.org. Retrieved 2021-05-03.

- ↑ Robert Francis Xavier Renehan (April 25, 1935 - April 26, 2019)

- ↑ Dieter Leisegang (November 25, 1942 - March 21, 1973) - German philosopher, author, and radio and television broadcaster. He graduated in 1969 from Johann Wolfgang Goethe University (Frankfurt am Main) with a doctorate in philosophy. While a student at the university, one of his teachers was German philosopher Julius Jakob Schaaf (October 1, 1910 - March 3, 1994). Leisegang studied Schaaf's "Universal Relational Theory" and developed it further into a "philosophy of relationship", which he then presented in detail in his doctoral dissertation titled Die drei Potenzen der Relation (Frankfurt: Heiderhoff, 1969) (The Three Powers of Relation). Leisegang's other published works on this subject include Dimension und Totalität: Entwurf einer Philosophie der Beziehung (Frankfurt: Heiderhoff, 1972) (Dimension and Totality: Outline of a Philosophy of Relationship), and Philosophie als Beziehungswissenschaft. Festschrift für Julius Schaaf (Frankfurt: H. Heiderhoff, 1974) (co-edited with Wilhelm Friedrich Niebel) (Philosophy as Relational Science. Festschrift for Julius Schaaf)

- ↑ Cherniss, Harold (1962). Aristotle's Criticism of Plato and the Academy, Russell and Russell, Inc., p. xi.

External links

- Werner Jaeger at the Database of Classical Scholars

- The Sather Professor - UC Berkeley Classics Department