| West Flemish | |

|---|---|

| West-Vlaams | |

| Native to | Belgium, Netherlands, France |

| Region | West Flanders |

Native speakers | (1.4 million cited 1998)[1] |

| Dialects | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | Either:vls – (West) Vlaamszea – Zeelandic (Zeeuws) |

| Glottolog | sout3292 Southwestern Dutchvlaa1240 Western Flemish |

| Linguasphere | 52-ACB-ag |

West Flemish is classified as Vulnerable by the UNESCO Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger | |

West Flemish (West-Vlams or West-Vloams or Vlaemsch (in French-Flanders), Dutch: West-Vlaams, French: flamand occidental) is a collection of Dutch dialects spoken in western Belgium and the neighbouring areas of France and the Netherlands.

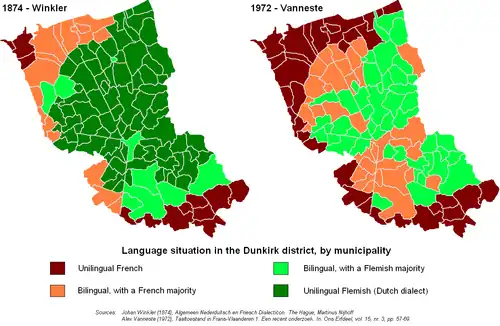

West Flemish is spoken by about a million people in the Belgian province of West Flanders, and a further 50,000 in the neighbouring Dutch coastal district of Zeelandic Flanders (200,000 if including the closely related dialects of Zeelandic) and 10-20,000 in the northern part of the French department of Nord.[1] Some of the main cities where West Flemish is widely spoken are Bruges, Dunkirk, Kortrijk, Ostend, Roeselare and Ypres.

West Flemish is listed as a "vulnerable" language in UNESCO's online Red Book of Endangered Languages.[2]

| This article is a part of a series on |

| Dutch |

|---|

| Low Saxon dialects |

| West Low Franconian dialects |

| East Low Franconian dialects |

Phonology

West Flemish has a phonology that differs significantly from that of Standard Dutch, being similar to Afrikaans in the case of long E, O and A. Also where Standard Dutch has sch, in some parts of West Flanders, West-Flemish, like Afrikaans, has sk. However, the best known traits are the replacement of Standard Dutch (pre-)velar fricatives g and ch in Dutch (/x, ɣ/) with glottal h [h, ɦ],. The following differences are listed by their Dutch spelling, as some different letters have merged their sounds in Standard Dutch but remained separate sounds in West Flemish. Pronunciations can also differ slightly from region to region.

- sch - /sx/ is realised as [ʃh], [sh] or [skʰ] (sh or sk).

- ei - /ɛi/ is realised as [ɛː] or [jɛ] (è or jè).

- ij - /ɛi/ is realised as [i] (short ie, also written as y) and in some words as [y].

- ui - /œy/ is realised as [y] (short ie, also written as y) and in some words as [i].

- au - /ʌu/ is realised as [ɔu] (ow)

- ou - /ʌu/ is realised as [ʊ] (short oe), it is very similar to the long "oe" that is also used in Standard Dutch ([u]), which can cause confusion

- e - /ɛ/ is realised as [æ] or [a].

- i - /ɪ/ is realised as [ɛ].

- ie - /i/ is longer [iː]

- aa - /aː/ is realised as [ɒː].

The absence of /x/ and /ɣ/ in West Flemish makes pronouncing them very difficult for native speakers. That often causes hypercorrection of the /h/ sounds to a /x/ or /ɣ/.

Standard Dutch also has many words with an -en (/ən/) suffix (mostly plural forms of verbs and nouns). While Standard Dutch and most dialects do not pronounce the final n, West Flemish typically drops the e and pronounces the n inside the base word. For base words already ending with n, the final n sound is often lengthened to clarify the suffix. That makes many words become similar to those of English: beaten, listen etc.

The short o ([ɔ]) can also be pronounced as a short u ([ɐ]), a phenomenon also occurring in Russian and some other Slavic languages, called akanye. That happens spontaneously to some words, but other words keep their original short o sounds. Similarly, the short a ([ɑ]) can turn into a short o ([ɔ]) in some words spontaneously.

The diphthong ui (/œy/) does not exist in West Flemish and is replaced by a long u ([y]) or a long ie ([i]). Like for the ui, the long o ([o]) can be replaced by an [ø] (eu) for some words but a [uo] for others. That often causes similarities to ranchers English.

Here are some examples showing the sound shifts that are part of the vocabulary:

| Dutch | West Flemish | English |

|---|---|---|

| vol (short o) | vul [vɐl] | full |

| zon (short o) | zunne [ˈzɐnːə] | sun |

| kom (short o) | kom* [kɔm] | come |

| boter (long o) | beuter [ˈbøtər] | butter |

| boot (long o) | boot [buot] | boat |

| kuiken | kiek'n [ˈkiːʔŋ̍] | chick |

| bruin | brun [bryn] | brown |

* This is as an example as a lot of words are not the same. The actual word used for kom is menne.

Grammar

Plural form

Plural forms in Standard Dutch most often add -en, but West Flemish usually uses -s, like the Low Saxon dialects and even more prominently in English in which -en has become very rare. Under the influence of Standard Dutch, -s is being used by fewer people, and younger speakers tend to use -en.

Verb conjugation

The verbs zijn ("to be") and hebben ("to have") are also conjugated differently.

| Dutch | West Flemish | English | Dutch | West Flemish | English |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| zijn | zyn | to be | hebben | èn | to have |

| ik ben | 'k zyn | I am | ik heb | 'k è | I have |

| jij bent | gy zyt | you are | jij hebt | gy èt | you have |

| hij is | ie is | he is | hij heeft | ie èt | he has |

| wij zijn | wydder zyn | we are | wij hebben | wydder èn | we have |

| jullie zijn | gydder zyt | you are | jullie hebben | gydder èt | you have |

| zij zijn | zydder zyn | they are | zij hebben | zydder èn | they have |

Double subject

West Flemish often has a double subject.

| Dutch | West Flemish | English |

|---|---|---|

| Jij hebt dat gedaan. | G' è gy da gedoan. | You have done that. |

| Ik heb dat niet gedaan. | 'K èn ekik da nie gedoan. | I didn't do that. |

Articles

Standard Dutch has an indefinite article that does not depend on gender, unlike in West Flemish. However, a gender-independent article is increasingly used. Like in English, n is pronounced only if the next word begins with a vowel sound.

| Dutch | West Flemish | English |

|---|---|---|

| een stier (m) | ne stier | a bull |

| een koe (f) | e koeje | a cow |

| een kalf (o) | e kolf | a calf |

| een aap (m) | nen oap | an ape |

| een huis (o) | en 'us | a house |

Conjugation of yes and no

Another feature of West Flemish is the conjugation of ja and nee ("yes" and "no") to the subject of the sentence. That is somewhat related to the double subject, but even when the rest of the sentence is not pronounced, ja and nee are generally used with the first part of the double subject. There is also an extra word, toet ([tut]), negates the previous sentence but gives a positive answer. It is an abbreviation of " 't en doe 't" - it does it.

Ja and nee can also all be strengthened by adding mo- or ba-. Both mean "but" and are derived from Dutch but or maar) and can be even used together (mobajoat).

| Dutch | West Flemish | English |

|---|---|---|

| Heb jij dat gedaan? - Ja / Nee | Èj gy da gedoan? - Joak / Nink | Did you do that? - Yes / No |

| Je hebt dat niet gedaan, hé? - Maar jawel | J'èt da nie gedoan, é? - Bajoat | You didn't do that, eh? - On the contrary (But yes I did.). |

| Heeft hij dat gedaan? - Ja / Nee | Èt ie da gedoan? - Joan / Nin (Joaj/Nij - Joas/Nis) | Did he do that? - Yes / No (Yes/No - Yes/No) |

| Gaan we verder? - Ja / Nee | Zyn we? - Joat / Ninck | Can we go? - Yes / No |

See also

- Flemish dialects

- Dutch dialects

- Flemish people (Flemings or Vlamingen)

- French Flemish

- Hebban olla vogala

- Westhoek

References

- 1 2 (West) Vlaams at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) (subscription required)

Zeelandic (Zeeuws) at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) (subscription required) - ↑ "UNESCO Interactive Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger". United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization. Archived from the original on 30 October 2010. Retrieved 2023-02-07.

Further reading

- Debrabandere, Frans (1999), "Kortrijk" (PDF), in Kruijsen, Joep; van der Sijs, Nicoline (eds.), Honderd Jaar Stadstaal, Uitgeverij Contact, pp. 289–299