West Memphis, Arkansas | |

|---|---|

| City of West Memphis | |

Areal view of Tilden Rodgers Sports Complex | |

Flag | |

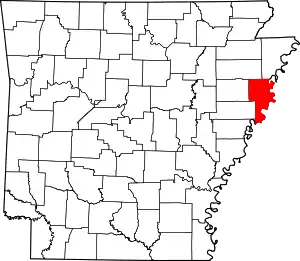

Location in Crittenden county and Arkansas | |

West Memphis Location in the United States | |

| Coordinates: 35°9′1″N 90°10′44″W / 35.15028°N 90.17889°W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| County | Crittenden |

| Townships |

|

| Founded | September 9, 1916 |

| Incorporated | May 7, 1927 |

| Named for | Memphis, Tennessee |

| Government | |

| • Type | Mayor–Council |

| • Mayor | Marco McClendon (I) |

| • Council | City Council |

| Area | |

| • Total | 28.94 sq mi (74.96 km2) |

| • Land | 28.84 sq mi (74.70 km2) |

| • Water | 0.10 sq mi (0.26 km2) |

| Elevation | 210 ft (60 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

| • Total | 24,520 |

| • Density | 850.15/sq mi (328.24/km2) |

| • Demonym | West Memphian |

| Time zone | UTC−6 (Central (CST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−5 (CDT) |

| ZIP codes | 72301, 72327, 72364, 72376 |

| Area code | 870 |

| FIPS code | 05-74540 |

| GNIS feature ID | 0078727[2] |

| Website | westmemphisar |

West Memphis is the largest city in Crittenden County, Arkansas, United States. The population was 26,245 at the 2010 census,[3] ranking it as the state's 18th largest city, behind Bella Vista. It is part of the Memphis metropolitan area, and is located directly across the Mississippi River from Memphis, Tennessee.

History

Pre-European habitation

Native Americans lived in the Mississippi River Valley for at least 10,000 years, although much of the evidence of their presence has been buried or destroyed. The people of the Mississippian Period were the last indigenous inhabitants of the West Memphis area. Mound City Road, located within the eastern portion of the West Memphis city limits, has a marker indicating that the villages of Aquixo (Aquijo) or Pacaha were in the area. Several mounds are still visible.

European exploration and settlement

Explorers from both Spain and France visited the area near West Memphis. Among those explorers were Hernando de Soto and his men from Spain and Father Jacques Marquette and Louis Jolliet from France. By the time French hunters and explorers entered the region, the Mississippian towns and other settlements had been abandoned. The original site of West Memphis came from Spanish land grants issued during the 1790s. Grants were given to Benjamin Fooy, John Henry Fooy, and Isaac Fooy in the Hopefield (Crittenden County) area and to William McKenney in the Bridgeport-West Memphis area.

Early history

In the summer of 1541, Spanish explorer Hernando De Soto crossed the Mississippi River into what is now Crittenden County with an army of over 300 conquistadors and almost as many captured Native American slaves. The Spanish found the land to be the most densely populated that they had seen since starting their journey on the Florida coast, two years earlier. The Spanish expedition departed Arkansas two years later, leaving behind numerous Old World diseases. It was 130 years before Europeans visited this region again. The French expedition of Joliet and Marquette in 1673 found none of the towns or people that the Spanish had documented; all that remained were the many mounds that still dot the landscape along the rivers and creeks. The original inhabitants, like the later settlers, were drawn to this region because of its fertile river bottom soil, abundant game, and thick forest.

First European settlement

The earliest recorded immigrant to the area was Benjamin Fooy, a native of Holland, who was sent in 1795 by the Spanish governor of the large area claimed by Spain to establish a settlement on the Mississippi River. He chose a location across the river from present-day Memphis. In 1797, the Spanish established Campo de la Esperanza,[4] which was a small fort along the Mississippi River. The Spanish abandoned the fort in 1802 and the area took its English translation "Field of Hope", which eventually became known as Hopefield shortly after the United States took possession of the Louisiana Territory.

Crittenden County

Crittenden County is bounded on the east by the Mississippi River and was established in 1825, eleven years before Arkansas became a state. Named after Robert Crittenden, the first secretary of the Arkansas Territory, the county had a population of 1,272 in 1830. Hopefield became the eastern terminal for the Memphis and Little Rock Railroad in 1857. However, the Civil War forced a halt to track construction just east of the St. Francis River in 1861.

Civil War and the end of Hopefield

During the summer of 1862, Memphis fell into the hands of the Union forces. Most Confederate soldiers were ferried across the river to Hopefield, Arkansas, and surrounding farms. Many of these soldiers were moved on to other battle fronts, but some remained to harass the Union forces and disrupt river traffic. This became such a problem that on February 19, 1863, four companies of Federal forces burned down the entire town. The town of Hopefield was rebuilt after the war but never regained the prominence it once held in Crittenden County. After the St. Francis Levee District began the levee system in the Arkansas Delta during the 1890s, what little remained of Hopefield became part of the Mississippi River flood plain and was washed away.

First settlement named West Memphis

An early settlement that was established for ferry operations between Memphis and Arkansas in the early 1880s was given the name West Memphis. This small settlement, located directly south of the present day Memphis & Arkansas Bridge, never incorporated and died out shortly after ferry traffic ceased due to the completion of the Frisco Bridge across the Mississippi River in 1892. In addition to its lost ferry operations, this area, in the same fashion as its northern neighbor Hopefield, became part of the Mississippi River flood plain in the 1890s.[5]

The entire area usually flooded in the spring until the St. Francis Levee District was established in 1893. However, private landowners along the Mississippi River built levees that were only three or four feet high. In 1912 and 1913, the St. Francis main levee broke, flooding the area from the Mississippi River to Forrest City in St. Francis County. The flood of 1913 was the last time the levee broke in Crittenden County.[6]

Founding of West Memphis

After the levee system was built and strengthened, Zack T. Bragg, a lumberman who had been logging in St. Francis County since 1905, purchased 300 acres of virgin timber and established a sawmill in 1914. The mill was located along a railroad spur and a dirt path that would eventually become Missouri Street in West Memphis.[6][7] Bragg also acquired the timbering rights to thousands of acres of adjacent land clearing the area that eventually gave way to fertile farmland and to the future West Memphis. The area around Bragg's Mill was known for the first few years as Bragg, Arkansas. The small community consisted of the mill, a commissary and boarding house, and a few dozen dwellings for workers.[8]

In 1914, another operation began two miles south of Bragg's Mill when William H. Hundhausen began plans for the Bolz Slack Barrell Cooperage plant located at the southern end of present-day 8th Street in West Memphis. The Bolz Cooperage, which was a stave mill, purchased a great quantity of acreage for its lumber operation. Within a short time of the mill's beginning, a small community developed. In 1917, highways 70 and 61 were established and clearing began through the future West Memphis.[9] With the threat of river flooding diminished by a strengthened levee, the establishment of two lumber operations and the building of two major U.S. highways, the small lumber communities grew rapidly. In 1920 the population was approximately 132 and by 1928, the population had grown to 350. The community incorporated as a city in 1927 with the name West Memphis. Zack T. Bragg, one of the city's founders, was elected as the first mayor and served for three consecutive one year terms. William H. Hundhausen, another founder of West Memphis, was elected as its third mayor and served from 1932 to 1944.[6]

Early 20th century

.jpg.webp)

The construction of the railroads, the establishment of lumber operations and the construction of two new U.S. highways fueled the growth of West Memphis. In 1930, the population reached 895. By 1940, the population grew to 2,225 and by the 1950 census, the population had more than quadrupled in size to 9,112, making West Memphis the fastest growing city in Arkansas. Due to the rapid growth of the city that grew from thick forests and swamps earlier in the 20th century, West Memphis was nicknamed the "Wonder City" in the mid-1930s.[10]

20th century growth

The first automobiles began crossing the Mississippi River at Memphis in 1917 by special roadways constructed on the Harahan Bridge, which was built for rail traffic and opened in 1916. This heralded the growth of the future West Memphis as its main street, U.S. Highway 70, known as Broadway Avenue, brought an influx of automobile traffic through the area. U.S. Highway 61, named Missouri Street in West Memphis, was constructed at the same time and its juncture with Highway 70 would become the epicenter of downtown West Memphis.[8]

West Memphis was officially incorporated in 1927 and continued to grow to become the largest city in Crittenden County. The availability of river and rail transportation transformed West Memphis into the manufacturing and distribution hub of the county. In the 1930s West Memphis, along with the rest of the Mississippi Delta, suffered due to the economic depression. However, the city grew and developed at a record pace. The most notable export of West Memphis from that era was its original blues music. At one time Sonny Boy Williamson, Howlin' Wolf, Robert Lockwood, Jr., and B.B. King lived in West Memphis.

The growth and development of the city's main commercial thoroughfare, Broadway Avenue, was instigated by the increased traffic and by demand for the industrial products produced and shipped through West Memphis by rail and river. Tourist courts, restaurants, hotels and other amenities geared toward the traveler were constructed along the traffic corridor through West Memphis. During the World War II years, transportation of soldiers and goods by road, river, and rail in the Memphis/West Memphis area created the need for lodging and other services. Construction in 1949 of a second automobile bridge across the Mississippi, connecting Memphis and West Memphis, created another influx of automobile traffic.

The buildings in the 700, 800 and 900 blocks of East Broadway reflect the growth of the city of West Memphis in the years 1930 to 1958. Until the national interstate highway system was opened in the late 1950s, diverting traffic away from former routes through the middle of America's towns, West Memphis' Broadway Avenue was the city's center of commerce, with retail stores, tourist courts and hotels and office buildings. Decline of Broadway Avenue was rapid after the traffic through the town diminished with the opening of the interstate highways. Although the three blocks of East Broadway contained in the West Memphis Commercial Historic District remain much as they appeared in the 1930s, 1940s, and 1950s, the remainder of the city's major traffic corridor, Broadway Avenue, has changed significantly.

World War II to the modern era

In the 1930s, 1940s, and 1950s, 8th Street was often called "Beale Street West", reflecting a music and nightlife scene to equal that in Memphis. Some places in West Memphis have been associated with entertainers such as B.B. King (who began his public entertaining at the Square Deal Café on South 16th Street) and Elvis Presley (who ate his first breakfast after being inducted into the U.S. Army at the Coffee Cup on East Broadway on March 24, 1958). Other night spots along Broadway Street included Willowdale Inn, the Cotton Club, and the Plantation Inn.

Legal greyhound racing began in the county in 1935. In the years that followed, the track closed several times—once for flooding, another due to World War II, and another time due to fire. However, the business currently known as Southland Park Gaming & Racing on North Ingram Boulevard has been in the same location since 1956 and is now open every day of the week, including 24 hours on weekends.

West Memphis began its role as a trucking hub with the opening of parts of Interstate 55 in the 1950s. With both I-55 and I-40 traveling toward the Mississippi River, West Memphis became known as the "crossroads of America" in the trucking industry. In 1973, a six-lane highway bridge, known as the Hernando de Soto Bridge and located north of the Harahan, opened as part of I-40.

In 1980, Leo Chitman was elected as the city's first African American mayor.[11] Current Mayor Marco McClendon, who became the youngest West Memphis Mayor to be sworn into office in 2019,[12] is African American as well.[13]

On December 14, 1987, a tornado killed six people and caused approximately $35 million in damage. The town had not recovered from the tornado damage when it flooded from 12 inches (300 mm) of rain on December 25, 1987. Additionally, 7 to 10 inches (180 to 250 mm) of snow fell on January 6, 1988. When the snow began to melt, this added to the already existing flood problems and the destruction caused by the tornado.

Some of the major employers in the city are Schneider National Carriers, Southland Park Gaming & Racing, Family Dollar Distribution, FedEx National LTL, and Robert Bosch Power Tools. Family Dollar Distribution and FedEx National LTL are located in the Mid-America Industrial Park west of the city.

The 1993 murders of three young boys and the subsequent convictions of Damien Echols, Jason Baldwin, and Jessie Misskelley, Jr. brought much unwanted attention to West Memphis. The three young men convicted were known as the West Memphis Three and the case brought about a great amount of public intrigue. Three documentaries have been made about the incident, the first being Paradise Lost: The Child Murders at Robin Hood Hills. Echols, Baldwin, and Misskelley were released from jail in 2011 after signing an Alford plea, which allowed them to plead guilty while maintaining their innocence. They were released with time served and placed on probation until 2021.[14]

Geography

West Memphis is located in eastern Crittenden County. It is bordered to the north by the city of Marion. A small piece of West Memphis extends south as far as the Mississippi River, but in most places the river is from 0.2 to 2 miles (0.32 to 3.22 km) south or east of the city limits. Downtown Memphis, Tennessee, is 8 miles (13 km) east of downtown West Memphis. According to the United States Census Bureau, West Memphis has a total area of 28.5 square miles (73.9 km2), of which 28.5 square miles (73.7 km2) is land and 0.077 square miles (0.2 km2), or 0.34%, is water.[3]

Ecologically, West Memphis is located on the border between the Northern Backswamps (western part of West Memphis) and Northern Holocene Meander Belts (eastern section of West Memphis) ecoregions within the larger Mississippi Alluvial Plain. The Northern Backswamps are a network of low-lying overflow areas and floodplains historically dominated by bald cypress, water tupelo, overcup oak, water hickory, and Nuttall oak forest subject to year-round or seasonal inundation. The Northern Holocene Meander Belts are the flat floodplains and former alignments of the Mississippi River, including levees, oxbow lakes, and point bars. Much of the wetlands and riverine habitat have been drained and developed for agricultural or urban land uses.[15] The Wapanocca National Wildlife Refuge, which preserves some of the year-round flooded bald cypress forest typical of this ecoregion prior to development for row agriculture lies north of West Memphis.

Demographics

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1930 | 895 | — | |

| 1940 | 3,369 | 276.4% | |

| 1950 | 9,112 | 170.5% | |

| 1960 | 19,374 | 112.6% | |

| 1970 | 26,070 | 34.6% | |

| 1980 | 28,138 | 7.9% | |

| 1990 | 28,259 | 0.4% | |

| 2000 | 27,666 | −2.1% | |

| 2010 | 26,245 | −5.1% | |

| 2020 | 24,520 | −6.6% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[16] | |||

2020 census

| Race | Num. | Perc. |

|---|---|---|

| White | 7,024 | 28.65% |

| Black or African American | 16,087 | 65.61% |

| Native American | 54 | 0.2% |

| Asian | 101 | 0.41% |

| Pacific Islander | 7 | 0.03% |

| Other/Mixed | 675 | 2.75% |

| Hispanic or Latino | 572 | 2.33% |

As of the 2020 United States Census, there were 24,520 people, 9,939 households, and 5,964 families residing in the city.

2010 census

As of the 2010 United States Census, there were 26,245 people living in the city. The racial makeup of the city was 63.3% Black, 33.7% White, 0.1% Native American, 0.4% Asian, <0.1% Pacific Islander, <0.0% from some other race and 0.8% from two or more races. 1.6% were Hispanic or Latino of any race.

2000 census

As of the census[18] of 2000, there were 27,666 people, 10,051 households, and 7,136 families living in the city. The population density was 1,044.3 inhabitants per square mile (403.2/km2). There were 11,022 housing units at an average density of 416.1 per square mile (160.7/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 55.93% Black or African American, 42.16% White, 0.21% Native American, 0.53% Asian, 0.02% Pacific Islander, 0.51% from other races, and 0.64% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 1.01% of the population.

There were 10,051 households, out of which 36.7% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 40.4% were married couples living together, 25.1% had a female householder with no husband present, and 29.0% were non-families. There were 553 unmarried partner households: 475 of both sexes, 52 same-sex male, and 26 same-sex female. 24.8% of all households were made up of individuals, and 8.6% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.70 and the average family size was 3.23.

In the city, the population was spread out, with 31.5% under the age of 18, 9.8% from 18 to 24, 28.2% from 25 to 44, 20.1% from 45 to 64, and 10.5% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 31 years. For every 100 females, there were 86.6 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 79.9 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $27,399, and the median income for a family was $32,465. Males had a median income of $29,977 versus $21,007 for females. The per capita income for the city was $13,679. About 23.7% of families and 28.3% of the population were below the poverty line, including 40.9% of those under age 18 and 22.3% of those age 65 or over.

Crime

West Memphis tends to have crime levels considerably above the national average.[19][20] For the year of 2006, the violent crime index was 1989.3 violent crimes committed per 100,000 residents. The national average was 553.5 crimes committed per 100,000 residents. For 2008, the total murder risk for the city was over two and a half times the United States average, the same applied when compared to the Arkansas state average. Other forms of crime were roughly the same with the exception of larceny which was slightly above the national average.[21] While the crime within West Memphis is typically high, it is relatively average when compared with its far larger neighbor Memphis, the same applies to other cities throughout the same region of the South.[22][23][24][25][26]

Economy

Primarily because of its central location and transportation infrastructure, West Memphis has become a hub for distribution and assembly operations. Healthcare is a noteworthy component of the city's economy, including Baptist Memorial Hospital – Crittenden, various clinics, medical suppliers, and nursing homes located in town.

The city lies at the point where two of the nation's most heavily traveled interstate highways, Interstate 40 and Interstate 55, intersect with the Mississippi River (a major cargo waterway) and large rail-lines operated by BNSF and Union Pacific.[27] Cable television, internet and digital phone service is offered through Comcast. AT&T provides telephone and internet service.

Distribution centers

Major operations include distribution centers for retailers such as Family Dollar,[28] Carvana, Bosch Tools and manufacturers such as Stateside Steel & Wire

Continuing nearly $40 million in expenditures in West Memphis since 1998, Ciba Specialty Chemicals began construction of a new $1.3 million, 7,000-square-foot (650 m2) laboratory facility in December 2003, which was completed in June 2004.[29]

Parks and recreation

Public parks

Public parks in the area include Franklin Park, Grimsley Park, Hicks Park, Hightower Park, Horton Park, Martin Luther King Jr. Park, Matthews Park, Rowe Park, Tenth Street Park, Tilden Rodgers Sports Complex and Worthington Park.[30]

West Memphis Gateway

The West Memphis Gateway serves as the main entrance to the city of West Memphis. The LED lighting for the overpass support beams light at night according to the season of the year.

Broadway Boulevard

Broadway Boulevard is the downtown district for the city of West Memphis. This downtown area has more than 84 stores and restaurants lining the street. Broadway also hosts blues singers and events in the city's "Blues on Broadway".

Gambling

West Memphis is one of only two cities in Arkansas (along with Hot Springs) with a venue for parimutuel gambling, antedating the casino developments in nearby Tunica County, Mississippi, by many years.

In the 1990s, Southland Greyhound Park, one of West Memphis' largest employers, saw its attendance and revenues decline drastically, with a corresponding economic impact on both the town and state. This was largely attributed to the rise of casino gambling in nearby Tunica, Mississippi. By 2002, Southland struggled to survive.[31]

Following an estimated $40 million investment by the park's owner[32] and the addition since 2006 of electronic games of skill and video poker machines,[33][34] Southland has added more than 300 new employees, making it the third largest employer in West Memphis with 660 employees.[32]

Education

College

Public schools

Most of West Memphis is served by the West Memphis School District while a portion of the city of West Memphis is located within the Marion Public School District.[36]

West Memphis district schools:

- Academies of West Memphis High School, grades 10–12

- East Junior High School, grades 7–9

- West Junior High School, grades 7–9

- Wonder Junior High School, grades 7–9

- Bragg Elementary School, kindergarten-6th grade

- Richland Elementary School, kindergarten-6th grade

- Faulk Elementary School, kindergarten-6th grade

- Jackson Elementary School, prekindergarten-6th grade

- Maddux Elementary School, kindergarten-6th grade

- Weaver Elementary School, kindergarten-6th grade

- Wonder Elementary School, kindergarten-6th grade

- [closed] Wedlock Elementary School, kindergarten-6th grade

Marion district schools:

- Marion High School (grades 10–12)

- Marion Junior High School (7–9)

- Marion Math Science and Technology (K-6)

- Marion Visual and Performing Arts (K-6)

- Herbert Carter Global Community Magnet (K-6)

Private schools

- West Memphis Christian School, prekindergarten-12th grade

- St. Michael's Catholic School [6]

Infrastructure

Major highways

- Interstate 40

- Interstate 55

- U.S. Highway 61

- U.S. Highway 63

- U.S. Highway 64

- U.S. Highway 70 (Broadway Boulevard)

- U.S. Highway 79

- Highway 77

- Highway 118

- Highway 191

Healthcare

From 1951 until its closure in 2014,[37] the community was served by Crittenden Regional Hospital, a 152-bed JCAHO Accredited facility.[38] Memphis-based Baptist Memorial Health System opened Baptist Memorial Hospital–Crittenden,[39] an 11-bed facility focusing on acute care, in December 2018.

Notable people

- Betty Blue, model and actress

- Corey Brewer, current European professional basketball player

- Marcus Brown, former NBA and European basketball player

- Shirley Brown, Grammy-nominated Stax recording artist

- Michael Cage, former NBA rebounding champion

- Jekalyn Carr, gospel musician

- Sid Eudy aka Sid Vicious or Sid Justice, former four-time World Heavyweight Wrestling Champion (WWE, WCW)

- Ike Harris, former NFL player

- Howlin' Wolf, blues guitarist, Chess Records artist, KWEM radio performer

- Wayne Jackson, trumpet player for The Memphis Horns

- B.B. King, blues guitarist, Modern Records artist, KWEM radio performer

- Keith Lee, former NBA player

- Junior Parker, blues musician

- Sonny Weems, current basketball player for Maccabi Tel Aviv of the Israeli Premier League and the Euroleague

- Junior Wells, blues harmonica player and vocalist

- Sonny Boy Williamson II, blues musician Trumpet Records artist, KWEM radio performer

- Warren Smith, rockabilly musician

- Yebba, singer and songwriter

See also

References

- ↑ "2020 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved October 29, 2021.

- 1 2 U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: West Memphis, Arkansas

- 1 2 "Geographic Identifiers: 2010 Demographic Profile Data (G001): Earle city, Arkansas". U.S. Census Bureau, American Factfinder. Archived from the original on February 12, 2020. Retrieved June 19, 2014.

- ↑ https://wikipedialibrary.wmflabs.org/about/ The Soldiers of Spain in Colonial Arkansas | Morris S. Arnold | Arkansas Historical Quarterly , Winter 2018, Vol. 77 Issue 4, p305-354, 50p

- ↑ Beauregard, Michael A. Images of American: West Memphis. Arcadia Publishing, 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 Woolfolk, Margaret Elizabeth. A History of Crittenden County. Southern Historical Press, 1993.

- ↑ Beauregard, Michael A. "Images of America: West Memphis". Arcadia Publishing, 2014.

- 1 2 Beauregard, Michael A. Images of America: West Memphis. Arcadia Publishing, 2014.

- ↑ Beauregard, Michael A. Images of America: West Memphis. Arcadia Press, 2014.

- ↑ Beauregard, Michael A. Images of America: West Memphis. Arcadia Publishing 2014.

- ↑ Stockley, Grif (November 12, 2020). "West Memphis revisited". Arkansas Times. Retrieved September 13, 2020.

- ↑ "Marco McClendon sworn in as West Memphis mayor". January 2, 2019.

- ↑ Nix, Ryan (February 3, 2020). "Tide Is Turning: Black Mayors Popping Up Across Arkansas". Retrieved September 13, 2020.

- ↑ Lohr, David (August 19, 2011). "'West Memphis Three' Free After Serving 17 Years". Huffington Post.

- ↑

This article incorporates public domain material from Woods, A.J., Foti, T.L., Chapman, S.S., Omernik, J.M.; et al. Ecoregions of Arkansas (PDF). United States Geological Survey.

This article incorporates public domain material from Woods, A.J., Foti, T.L., Chapman, S.S., Omernik, J.M.; et al. Ecoregions of Arkansas (PDF). United States Geological Survey.{{citation}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) (color poster with map, descriptive text, summary tables, and photographs). - ↑ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ↑ "Explore Census Data". data.census.gov. Retrieved December 7, 2021.

- ↑ "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ↑ "Regional Estimates - Crime in the United States 2007". www.fbi.gov. Archived from the original on November 29, 2014.

- ↑ "Southern states have highest murder rates in U.S". Jet. 1995. Archived from the original on July 10, 2012.

- ↑ "West Memphis, AR Demographics Summary". CLRSearch. Archived from the original on September 16, 2009. Retrieved October 17, 2011.

- ↑ "Richmond, VA Crime Rate Indexes". CLRSearch. Retrieved October 17, 2011.

- ↑ "West Memphis, AR Crime Rate Indexes". CLRSearch. Retrieved October 17, 2011.

- ↑ "West Memphis, AR Crime Rate Indexes". CLRSearch. Retrieved October 17, 2011.

- ↑ "Real Estate, Foreclosures, Demographics and Luxury Property Listings". CLRSearch.com. Retrieved October 17, 2011.

- ↑ "West Memphis, AR Crime Rate Indexes". CLRSearch. Retrieved October 17, 2011.

- ↑ "West Memphis Economic Development". www.westmemphis.com. Retrieved April 3, 2018.

- ↑ "Family Dollar Leverages Strong West Memphis Distribution Operation into 6,000th Store". Westmemphis.com. February 23, 2006. Retrieved October 17, 2011.

- ↑ "New Laboratory at the Ciba West Memphis plant". Ciba News. Ciba. September 4, 2004. Retrieved September 3, 2008.

- ↑ "Parks & Facilities | West Memphis, AR". www.westmemphisutilities.com.

- ↑ Whitsett, Jack (January 14, 2002). "Southland yearns for dogs' glory days". Arkansas Business Journal. Arkansas Business Limited Partnership. Retrieved September 4, 2008.

- 1 2 Editorial (May 4, 2007). "New games make Southland park more competitive". Memphis Business Journal. American City Business Journals. Retrieved September 4, 2008.

- ↑ "Southland Casino | Slots, Live Table Games, Racing | West Memphis, AR". www.southlandcasino.com.

- ↑ Martin, Dixie (March 29, 1993). "Arkansas Business".

- ↑ "ASU Mid-South – West Memphis, Arkansas -". ASU Mid-South – West Memphis, Arkansas. Retrieved April 3, 2018.

- ↑ "SCHOOL DISTRICT REFERENCE MAP (2010 CENSUS): Crittenden County, AR" (PDF). U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved May 14, 2018.

- ↑ "Hospital moves into West Memphis location". kait8.com. October 2, 2018. Retrieved February 22, 2019.

- ↑ "Quality Report - QualityCheck.org". www.qualitycheck.org. Retrieved April 3, 2018.

- ↑ "New Baptist Memorial Hospital opens its doors in Crittenden County". WREG.com. December 13, 2018. Retrieved February 22, 2019.

External links

- Official website

Geographic data related to West Memphis, Arkansas at OpenStreetMap

Geographic data related to West Memphis, Arkansas at OpenStreetMap - West Memphis, Arkansas at Ballotpedia

- West Memphis Chamber of Commerce

- West Memphis Public Library