_and_the_Treasury_Building_(red).jpg.webp) An aerial photo shows the East Wing of the White House (banded in yellow) and the Treasury Building (banded in red), the entry and exit points of the White House to Treasury Building tunnel. | |

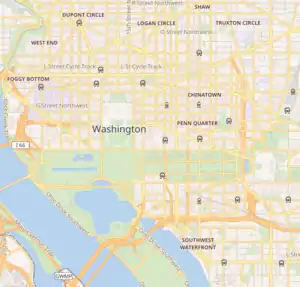

Location of the White House to Treasury Building tunnel in Washington, D.C. | |

| Overview | |

|---|---|

| Location | Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Coordinates | 38°53′51″N 77°02′06″W / 38.89750°N 77.03500°W |

| Start | White House |

| End | United States Treasury Building |

| Operation | |

| Work begun | 1941 |

| Owner | United States government |

| Operator | White House Military Office[1] |

| Character | pedestrian |

| Technical | |

| Length | 761 feet (232 m) |

| Tunnel clearance | 7 feet (2.1 m) |

| Width | 10 feet (3.0 m) |

The White House to Treasury Building tunnel is a 761-foot (232 m) subterranean structure in Washington, D.C. that connects a sub-basement of the East Wing of the White House to the areaway which surrounds the United States Treasury Building. It was initially constructed in 1941 to allow the evacuation of the president from the White House to underground vaults inside the Treasury in an emergency.

History

Background

Using the sturdy Treasury Building as a refuge of last resort has some precedent. Immediately after the Battle of Fort Sumter in 1861, there was concern about an imminent attack on Washington.[2] General Winfield Scott had the building readied to be used as a "last stand" by the federal government in the event the capital city was overrun.[3] The exterior of the building was ringed with sandbags and soldiers, and inside corridors and hallways leading to the underground vaults were barricaded "floor to ceiling". In the event of an unstoppable assault against the capital, plans had been drawn up for surviving U.S. Army forces to fight from three centers of final resistance, with the Treasury Building as the "citadel" of the third.[2] Under the army's plans, troops assigned to defend the White House would fight a delaying action in President's Park to cover the evacuation of Abraham Lincoln into the Treasury vaults.[2]

Early tunnel rumors

In the early 1930s, a decade before the tunnel was constructed, a rumor circulated that such a passageway already existed connecting the White House to the Treasury Building. According to one account, the rumor started as a joke among journalists covering the White House but gained serious traction, with some accounts even suggesting that Secretary Of The Treasury Ogden L. Mills was secretly accessing the White House via the purported passage to meet with President Herbert Hoover.[4]

World War II

Shortly after the Pearl Harbor attack, in December 1941, construction began on a hardened bunker to the east of the White House grounds that would provide a secure refuge for the president in the event of an air raid against the capital city. The East Wing was built on top of the bunker to hide the facility's construction from the public.[5][6] This facility would later become the Presidential Emergency Operations Center.[7]

As a stop-gap measure, the fortified vaults in the basement of the United States Treasury Building were converted into living quarters for the president and his family to be used if an attack came before the bunker's completion. Unlike the White House, which was a fragile structure[8] with what was then a shallow basement, the Treasury Building has a deep basement built into a foundation of granite, and its vaults are nested into stone. The ten-room presidential suite sat two floors below the cash room behind a steel bank door and was described as "every bit as nice as a suite at the Mayflower Hotel". The tunnel connecting the White House to the open areaway of the Treasury Building was excavated to allow the president's evacuation from one building to the other without the need to make the crossing outdoors.[5][6][9]

Efforts to protect the secrecy of the East Wing bunker and the White House to Treasury Building tunnel were largely fruitless. Despite a censorship order against media reporting, the existence of the bunker project was revealed by Republican United States Congressman Clare Hoffman in a floor debate in the United States House of Representatives in late December 1941. Hoffman objected to the cost and suggested the Treasury Building had adequate space to house the president and "Mrs. Roosevelt, Mayor LaGuardia, and their friend Sidney Hillman" because "there's nothing in the treasury vaults except IOU's anyway".[10]

Tunnel of Love

In later years, the tunnel was used by persons who needed to exit or depart the White House without public or press attention. Tricia Nixon and her husband, Edward F. Cox, left the White House via the tunnel after their 1972 Rose Garden wedding.[1]

According to Bill Gulley, longtime head of the White House Military Office, the tunnel was used by male White House aides to sneak their girlfriends and mistresses into the building to have sexual intercourse in the Lincoln Bedroom during the presidencies of Lyndon Johnson and Jimmy Carter.[lower-alpha 1][1] Lyndon Johnson also used the tunnel to avoid Vietnam War protesters when departing the White House.[11] An allegation that the White House to Treasury Building tunnel was used by Bill Clinton to facilitate extramarital liaisons has been discredited.[12][13]

A 1996 fire in the Treasury Building led the National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) to investigate fire safety around the building. The investigation showed no smoke detectors and fire barrier separation in the tunnel.[14]

Design

The 761-foot (232 m) tunnel, which passes underneath the street, is 7 feet (2.1 m) tall and 10 feet (3.0 m) wide.[6][13] It is not built in a straight line, but rather in a zig-zag pattern, to lessen the concussion from a direct bomb hit.[13] At various points along the tunnel, there are small rooms that, at one time, were equipped with cots so the tunnel could be used as a shelter.[1]

The tunnel is guarded by the Secret Service and includes cameras, alarms, and cipher locks.[1]

Related tunnels

Tunnels connecting the Treasury

The Treasury Building is the center of a network of tunnels. In addition to the tunnel connecting it to the White House, another connects to the Treasury Annex and H Street NW, constructed in 1919 and known since 2015 as Freedman's Bank Building.[11][15][16] Unlike the White House to Treasury Building tunnel, which was constructed as an emergency exit, the other tunnel was built to facilitate freight movement and access to utility lines.

Tunnel "Project ZP"

According to a 1996 issue of U.S. News & World Report, a 150-foot (46 m) tunnel was dug into the White House connecting the Oval Office to a location in the East Wing. The tunnel is purportedly accessed through a door adjacent to the president's restroom, which leads to a staircase used to enter the tunnel. The excavation of this tunnel, called "Project ZP", was undertaken in 1987 to provide a route for the president to be quickly and privately moved to the Presidential Emergency Operations Center in the event of an emergency. During the last days of the Reagan presidency, the Project ZP tunnel was allegedly used, in combination with the White House to Treasury Building tunnel, to allow Richard Nixon discreet access to the Oval Office for at least one consultation with Ronald Reagan.[17][18]

White House Big Dig

During the 2011 White House Big Dig, a tunnel was excavated near the West Wing. According to officials, that tunnel was intended for access to utilities.[19]

White House tunnels in fiction

- In the 1993 motion picture Dave, a tunnel leads from the White House to nearby Lafayette Square.[20][21]

- A tunnel to Lafayette Park, said to have been created by Abraham Lincoln, also features in the 1997 thriller Murder at 1600, based on the novel Murder in the White House by Margaret Truman, daughter of President Harry S. Truman.[20]

See also

Notes

- ↑ Gulley claims that a White House butler organized the access, which occurred during periods when the president was not in residence, in exchange for rides aboard Air Force One.[1]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Kessler, Ronald (1996). Inside the White House. Simon and Schuster. pp. 14–15. ISBN 0671879197.

- 1 2 3 Lockwood, John (2011). The Siege of Washington: The Untold Story of the Twelve Days That Shook the Union. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0199830738.

- ↑ Guelzo, Allen (November 2007). "Abraham Lincoln and the Development of the "War Powers" of the Presidency". The Federal Lawyer.

- ↑ "Myth Is Exploded Of Treasury Tunnel From White House". Cincinnati Enquirer. September 22, 1935. Retrieved February 11, 2017.

- 1 2 Seale, William. "Secret Spaces at the White House?". White House History. White House Historical Association. Retrieved February 11, 2017.

- 1 2 3 Klara, Robert (2013). The Hidden White House: Harry Truman and the Reconstruction of America's Most Famous Residence. Macmillan. pp. 157–158. ISBN 1250022932.

- ↑ Brower, Kate (September 11, 2016). "Inside the White House on September 11". Fortune. Retrieved February 11, 2017.

- ↑ Klara, Robert (2013). The Hidden White House: Harry Truman and the Reconstruction of America’s Most Famous Residence. Macmillan. pp. 99–100, 157–158. ISBN 1250022932.

- ↑ Klara, Robert (2013). The Hidden White House: Harry Truman and the Reconstruction of America's Most Famous Residence. Macmillan. pp. 99–100, 157–158. ISBN 1250022932.

- ↑ "Bomb Shelter is Being Built for Roosevelts". Chicago Tribune. December 20, 1941. Retrieved February 11, 2017.

- 1 2 Slovick, Matt (1997). "Dave". The Washington Post. Retrieved February 11, 2017.

- ↑ Plotz, David (July 25, 1996). "The Logistics of Presidential Adultery". Salon. Retrieved February 11, 2017.

- 1 2 3 Puleo, Stephen (2016). American Treasures: The Secret Efforts to Save the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution and the Gettysburg Address. Macmillan. p. 82-83. ISBN 1250065747.

- ↑ "Treasury Building Fire Washington, DC". NFPA. 26 June 1996. Retrieved 5 October 2019.

- ↑ BEP History (PDF). Bureau of Engraving and Printing. 2004. p. 7.

- ↑ Latimer, Louise Payson (1924). Your Washington and Mine. Charles Scribner's Sons. p. 161.

- ↑ Saltonstall, Dave (June 30, 1996). "DIG IT: BILL HAS SECRET TUNNEL PASSAGE LINKS OVAL OFFICE WITH LIVING QUARTERS". New York Daily News. Retrieved February 12, 2017.

- ↑ "Clinton's Oval Office". U.S. News & World Report. 1996. Retrieved February 24, 2016.

- ↑ "White House 'Big Dig': West Wing entrance fenced off". The Washington Post. Associated Press. April 4, 2011. Retrieved February 14, 2017.

- 1 2 "The White House in the Movies & TV". The White House Museum. Retrieved 2 March 2017.

- ↑ Dave (film). Warner Bros. 1993.